CONCLUSION As the Study Is an Attempt to Understand the Changes That Occurred in the Malabar During the Period of the Eighteenth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bugs R All FINAL Apr 2014 R

ISSN 2230 ! 7052 Newsletter of the $WIU4#NNInvertebrate Conservation & Information Network of South Asia (ICINSA) No. 21, April 2014 Photo: Aniruddha & Vishal Vishal Aniruddha & Photo: Contents Pages !"#$%&'(')*$+",-$.%+"/0"1-)2"3%%4&%,"')"5)*)*"67*$*47'"8*(#-,"/0"6*)2*&/$%"9)'.%$,'4+"3+"!"#$%%&'()#*"#+,'-.%/)#0"#1,'-23)#*"# 4'5'/,'6('-#'67#1"8"#9'-2:;<:('-'## # #"""## """## """# """## """## """## """# """######### ########=>? :%;"<%=/$>"/0"!"#"$%&'#(' '()*(+&',&-('.?'=/"@A@@"B8/&%/#4%$*C"D%)%3$'/)'>*%C"8)/>*&/)')'E"0$/("F)>'*";5#@"#$"#A%B7%#C#D"#E'."""""GHI J>/)*4*"BF),%=4*E"0*-)*"/0"K*$*>//$L"M*))-$L"M%$*&*L"N/-47"F)>'*";5#@26'5'6#!"#8'2-O""""## """## """# """## """### ###"""""PH@Q <%=/$>"/0"&/)2H7/$)%>"2$*,,7/##%$L"0*%12-2,2*3$4".(-%,252*"N4/&&L"@RSR"BJ$47/#4%$*C"D%T2/)''>*%E"0$/("U*7*$*,74$*L"F)>'*L" ;'47"*>>'V/)*&">'*2)/,V="=7*$*=4%$,";5#F"#4"#9G.2)#H"!"#D,'I'6%##'67#1"*"#H'2(I'7 """## """## """# """## """## ########@@H@W :/4%"/)"47%"X$,4",'27V)2"/0"5%$>/)Y,"5-(#')2"!)4L"6"*$&1-"#42'.'"5#"#2*L"5%$>/)"@S@I"BZ+(%)/#4%$*L"[/$('='>*%L"?/)%$')*%E" ')"M*$)*&*"6'$>"N*)=4-*$+L"<*'2*>"1',4$'=4L"U*7*$*,74$*L"F)>'*";5#J62-<77,'#$,':G-2('-##C#@2/,'.#0'/'. ## """## """######################@\H@G ['$,4"$%=/$>"/0"#7/4/4*]',"')"47%"U'&%V)*%L"^+=*%)'>*%";5#J"8"#02KK'#'67#*"#*5:GG6 """ """## """## """## """"""""@I 1'.%$,'4+"*)>",%*,/)*&"/==-$$%)=%"/0"3-_%$`'%,"*4"5';*a'"9)'.%$,'4+"8*(#-,L"b;*&'/$L"U*>7+*"?$*>%,7" ;5#82.'7-2#$'/B<&L'#'67#0"#4"#0'G """## """## """# """## """## """## """ """## """## """## """#"""""""""""""""""""""@PH"WQ 6'/&/2+"/0"47%"(/47"7&#"-"'#*%".43*#",""8$*(%$"B^%#'>/#4%$*C"^*,'/=*(#'>*%E"/)"F)>'*)"6*>*("D$%%.0&*8%-"5%".,"#"$$" -

Power Politics in Kolathunadu (1663-1697)

The Ali Rajas of Cannanore: status and identity at the interface of commercial and political expansion, 1663-1723 Mailaparambil, J.B. Citation Mailaparambil, J. B. (2007, December 12). The Ali Rajas of Cannanore: status and identity at the interface of commercial and political expansion, 1663-1723. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/12488 Version: Not Applicable (or Unknown) Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/12488 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). CHAPTER SIX POWER POLITICS IN KOLATHUNADU (1663-1697) In the month of October 1690, three Dutch soldiers deserted from the Dutch fortress in Cannanore and were caught by the Nayars of the Kolathiri prince, Keppoe Unnithamburan, in Maday—a place some twenty kilometres to the north of Cannanore.1 Although they tried to hide their real identity by claiming first that they were English and later Portuguese, the Nayars who were sent by the Company to track them successfully exposed their pretensions. Realizing the graveness of the situation, the soldiers desperately pleaded with the Prince not to extradite them to the Company for fear of capital punishment. Moved by their pathetic imploring, the Prince took them under his protection and ordered the Company Nayars to turn back, stating that he would take them to Cannanore personally, which, in fact, did not happen. The Company servants complained about this incident to the Ali Raja. The latter assured them he would settle the issue by promising to advise and caution the inexperienced young prince regarding this issue. -

Service Electoral Roll - 2017

SERVICE ELECTORAL ROLL - 2017 DIST_NO & NAME: 2 Kannur AC_NO & NAME:- 9 9-IRIKKUR ECI CODE NAME SEX TYPE HOUSE ADDRESS REGIMENTAL ADDRESS 1361573 TISSAN N PHILIP M M NELLIKKAMANNL Army ASC Records (South) NEDIYANGA TALIPARAMBA Agaram Post, Bangalore-07 CHEMPANTHOTTY 670631 1356308 TIJU JOSEPH M M PUTHUPARAMBIL Army PARIPPAI ASC Records (South) CHENGALAYI TALIPARAMBA Agaram Post, Bangalore-07 CHENGALAYI 670631 1372308 LAKSHMANAN MC M M KRISHNA KRIPA Army ASC Records (South) CHUZHALI TALIPARAMBA Agaram Post, Bangalore-07 CHUZHALI 670631 1370898 RAHIL RAJ MR M M 290, METTUMPURATH Army - ASC Records (South) VELLOD THALIPARAMBH Agaram Post, Bangalore-07 MANNAKKADAVU 1370853 BENNY E J M M Army ASC Records (South) VELLADE TALIPARAMBA Agaram Post, Bangalore-07 VELLADE 1370220 M KUNHI KRISHNAN M M Army ASC Records (South) CHUZHALI TALI PARAMBA Agaram Post, Bangalore-07 CHUZHALI 1369695 SANTOSH MR M M Army ASC Records (South) ALAKODE TALIPARAMBA Agaram Post, Bangalore-07 KARUVANCHAL 670571 1367427 K P NISHANTH M M Army ASC Records (South) ULIKKAL TALIPPARAMBA Agaram Post, Bangalore-07 ULIKKAL 1367818 SUNIL UMAR V K M M VETTUTHURUTHE Army ASC Records (South) PAYYAVOOR TALIPARAMBA Agaram Post, Bangalore-07 PAYYAOOR 670633 1001250 DILEEP KUMAR P M M MAVILA VEEDU Army SREEKANDAPURAM ASC Records (South) SREEKANDAPURAM TALIPARAMBA Agaram Post, Bangalore-07 CHERIKKODE 1363764 SREELAL K M M KALLEN HOUSE Army NIL ASC Records (South) CHENGALAYY THALIPARAMBA Agaram Post, Bangalore-07 CHENGALAYI 670631 998085 JYOTHISH K P M M SARADHA NILAM Army ASC Records -

Requiring Body SIA Unit

SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT STUDY FINAL REPORT LAND ACQUISITION FOR THE CONSTRUCTION OF OIL DEPOT &APPROACH ROAD FOR HPCL/BPCL AT PAYYANUR VILLAGE IN KANNUR DISTRICT 15th JANUARY 2019 Requiring Body SIA Unit RAJAGIRI outREACH HINDUSTAN PETROLEUM Rajagiri College of Social Sciences CORPORATION LTD. Rajagiri P.O, Kalamassery SOUTHZONE Pin: 683104 Phone no: 0484-2550785, 2911332 www.rajagiri.edu 1 CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1.1 Project and Public Purpose 1.2 Location 1.3 Size and Attributes of Land Acquisition 1.4 Alternatives Considered 1.5 Social Impacts 1.6. Mitigation Measures CHAPTER 2 DETAILED PROJECT DESCRIPTION 2.1. Background of the Project including Developers background 2.2. Rationale for the Project 2.3. Details of Project –Size, Location, Production Targets, Costs and Risks 2.4. Examination of Alternatives 2.5. Phases of the Project Construction 2.6.Core Design Features and Size and Type of Facilities 2.7. Need for Ancillary Infrastructural Facilities 2.8.Work force requirements 2.9. Details of Studies Conducted Earlier 2.10 Applicable Legislations and Policies CHAPTER 3 TEAM COMPOSITION, STUDY APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY 3.1 Details of the Study Team 3.2 Methodology and Tools Used 3.3 Sampling Methodology Used 3.4. Schedule of Consultations with Key Stakeholders 3.5. Limitation of the Study CHAPTER 4 LAND ASSESSMENT 4.1 Entire area of impact under the influence of the project 4.2 Total Land Requirement for the Project 4.3 Present use of any Public Utilized land in the Vicinity of the Project Area 2 4.4 Land Already Purchased, Alienated, Leased and Intended use for Each Plot of Land 4.5. -

76179-Sfs English Med School

BASIC DETAIL 76179-S F S ENGLISH MED SCHOOL KANNUR KERALA Dated : 21/08/2019 S F S ENGLISH MED SCHOOL KANNUR SCHOOL CODE 76179 SCHOOL NAME KERALA S F S ENGLISH MEDIUM AFFILIATION ADDRESS SCHOOL,VETTIAPPALLY 931202 CODE VAYAL,THANNA P O PRINCIPAL'S PRINCIPAL MR JAISMON FRANCIS CONTACT 9481404007 NUMBER PRINCIPAL'S PRINCIPAL'S EMAIL ID [email protected] RETIREMENT 15/11/2039 DATE SCHOOL'S CONTACT SCHOOL'S 0497-2734985 [email protected] NUMBER EMAIL ID SCHOOL'S FAX SCHOOL'S WEBSITE www.sfsschoolknr.com 04972734985 NUMBER YEAR OF LANDMARK NEAR SCHOOL N/R Andathode Madrasa 2003 ESTABLISHMENT AFFILIATION AFFILIATION VALIDITY 2017 TO 2022 PROVISIONAL STATUS NAME OF THE Kerala Fransalian REGISTRATION TRUST/SOCIETY/COMPANY 29/06/1973 Educational Society DATE REGISTERED WITH SOCIETY REGISTRATION REGISTRATION PERMANENT Education S.No.K.31 NUMBER VALIDITY REGISTRATION General Education(N) NOC ISSUING NOC ISSUING AUTHORITY 31/07/2012 Department, Govt of Kerala DATE NON PROPRIETY CHARACTER NO OBJECTION AFFIDAVIT/NON VIEW (1) VIEW (2) CERTIFICATE PROFIT COMPANY AFFIDAVIT FACULTY DETAILS 76179--S F S ENGLISH MED SCHOOL KANNUR KERALA Dated: 21/08/2019 TOTAL NUMBER OF TEACHERS (ALL CLASSES) 26 NUMBER OF PGTs 6 NUMBER OF TGTs 4 NUMBER OF PRTs 12 NUMBER OF PETs 1 OTHER NON-TEACHING STAFF 7 NUMBER OF MANDATORY TRAINING QUALIFIED NUMBER OF TRAININGS ATTENDED BY 15 5 TEACHERS FACULTY SINCE LAST YEAR WHETHER COUNSELLOR AND WELLNESS WHETHER SPECIAL EDUCATOR APPOINTED? TEACHER APPOINTED? HAS MANDATORY TRAINING OF TEACHERS AS PER THE TRAINING POLICY (SECTION-16 -

List of Offices Under the Department of Registration

1 List of Offices under the Department of Registration District in Name& Location of Telephone Sl No which Office Address for Communication Designated Officer Office Number located 0471- O/o Inspector General of Registration, 1 IGR office Trivandrum Administrative officer 2472110/247211 Vanchiyoor, Tvpm 8/2474782 District Registrar Transport Bhavan,Fort P.O District Registrar 2 (GL)Office, Trivandrum 0471-2471868 Thiruvananthapuram-695023 General Thiruvananthapuram District Registrar Transport Bhavan,Fort P.O District Registrar 3 (Audit) Office, Trivandrum 0471-2471869 Thiruvananthapuram-695024 Audit Thiruvananthapuram Amaravila P.O , Thiruvananthapuram 4 Amaravila Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2234399 Pin -695122 Near Post Office, Aryanad P.O., 5 Aryanadu Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0472-2851940 Thiruvananthapuram Kacherry Jn., Attingal P.O. , 6 Attingal Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0470-2623320 Thiruvananthapuram- 695101 Thenpamuttam,BalaramapuramP.O., 7 Balaramapuram Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2403022 Thiruvananthapuram Near Killippalam Bridge, Karamana 8 Chalai Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2345473 P.O. Thiruvananthapuram -695002 Chirayinkil P.O., Thiruvananthapuram - 9 Chirayinkeezhu Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0470-2645060 695304 Kadakkavoor, Thiruvananthapuram - 10 Kadakkavoor Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0470-2658570 695306 11 Kallara Trivandrum Kallara, Thiruvananthapuram -695608 Sub Registrar 0472-2860140 Kanjiramkulam P.O., 12 Kanjiramkulam Trivandrum Sub Registrar 0471-2264143 Thiruvananthapuram- 695524 Kanyakulangara,Vembayam P.O. 13 -

Mehendale Book-10418

Tipu as He Really Was Gajanan Bhaskar Mehendale Tipu as He Really Was Copyright © Gajanan Bhaskar Mehendale First Edition : April, 2018 Type Setting and Layout : Mrs. Rohini R. Ambudkar III Preface Tipu is an object of reverence in Pakistan; naturally so, as he lived and died for Islam. A Street in Islamabad (Rawalpindi) is named after him. A missile developed by Pakistan bears his name. Even in India there is no lack of his admirers. Recently the Government of Karnataka decided to celebrate his birth anniversary, a decision which generated considerable opposition. While the official line was that Tipu was a freedom fighter, a liberal, tolerant and enlightened ruler, its opponents accused that he was a bigot, a mass murderer, a rapist. This book is written to show him as he really was. To state it briefly: If Tipu would have been allowed to have his way, most probably, there would have been, besides an East and a West Pakistan, a South Pakistan as well. At the least there would have been a refractory state like the Nizam's. His suppression in 1792, and ultimate destruction in 1799, had therefore a profound impact on the history of India. There is a class of historians who, for a long time, are portraying Tipu as a benevolent ruler. To counter them I can do no better than to follow Dr. R. C. Majumdar: “This … tendency”, he writes, “to make history the vehicle of certain definite political, social and economic ideas, which reign supreme in each country for the time being, is like a cloud, at present no bigger than a man's hand, but which may soon grow in volume, and overcast the sky, covering the light of the world by an impenetrable gloom. -

List of Lacs with Local Body Segments (PDF

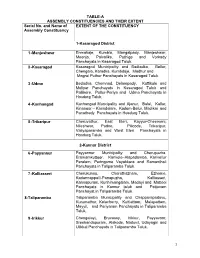

TABLE-A ASSEMBLY CONSTITUENCIES AND THEIR EXTENT Serial No. and Name of EXTENT OF THE CONSTITUENCY Assembly Constituency 1-Kasaragod District 1 -Manjeshwar Enmakaje, Kumbla, Mangalpady, Manjeshwar, Meenja, Paivalike, Puthige and Vorkady Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 2 -Kasaragod Kasaragod Municipality and Badiadka, Bellur, Chengala, Karadka, Kumbdaje, Madhur and Mogral Puthur Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk. 3 -Udma Bedadka, Chemnad, Delampady, Kuttikole and Muliyar Panchayats in Kasaragod Taluk and Pallikere, Pullur-Periya and Udma Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 4 -Kanhangad Kanhangad Muncipality and Ajanur, Balal, Kallar, Kinanoor – Karindalam, Kodom-Belur, Madikai and Panathady Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 5 -Trikaripur Cheruvathur, East Eleri, Kayyur-Cheemeni, Nileshwar, Padne, Pilicode, Trikaripur, Valiyaparamba and West Eleri Panchayats in Hosdurg Taluk. 2-Kannur District 6 -Payyannur Payyannur Municipality and Cherupuzha, Eramamkuttoor, Kankole–Alapadamba, Karivellur Peralam, Peringome Vayakkara and Ramanthali Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 7 -Kalliasseri Cherukunnu, Cheruthazham, Ezhome, Kadannappalli-Panapuzha, Kalliasseri, Kannapuram, Kunhimangalam, Madayi and Mattool Panchayats in Kannur taluk and Pattuvam Panchayat in Taliparamba Taluk. 8-Taliparamba Taliparamba Municipality and Chapparapadavu, Kurumathur, Kolacherry, Kuttiattoor, Malapattam, Mayyil, and Pariyaram Panchayats in Taliparamba Taluk. 9 -Irikkur Chengalayi, Eruvassy, Irikkur, Payyavoor, Sreekandapuram, Alakode, Naduvil, Udayagiri and Ulikkal Panchayats in Taliparamba -

Details of Crushers in Kannur District As on the Date of Completion Of

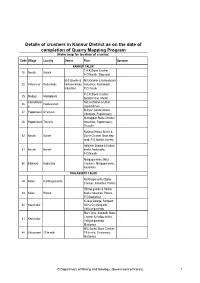

Details of crushers in Kannur District as on the date of completion of Quarry Mapping Program (Refer map for location of crusher) Code Village Locality Owner Firm Operator KANNUR TALUK T.A.K.Stone Crusher , 16 Narath Narath P.O.Narath, Step road M/S Granite & M/S Granite & Hollowbricks 20 Valiyannur Kadankode Holloaw bricks, Industries, Kadankode , industries P.O.Varam P.C.K.Stone Crusher, 25 Madayi Madaippara Balakrishnan, Madai Cherukkunn Natural Stone Crusher, 26 Pookavanam u Jayakrishnan Muliyan Constructions, 27 Pappinisseri Chunkam Chunkam, Pappinissery Muthappan Stone Crusher 28 Pappinisseri Thuruthi Industries, Pappinissery, Thuruthi National Hollow Bricks & 52 Narath Narath Stone Crusher, Near step road, P.O.Narath, Kannur Abhilash Granite & Hollow 53 Narath Narath bricks, Neduvathu, P.O.Narath Maligaparambu Metal 60 Edakkad Kadachira Crushers, Maligaparambu, Kadachira THALASSERY TALUK Karithurparambu Stone 38 Kolari Karithurparambu Crusher, Industries, Porora Hill top granite & Hollow 39 Kolari Porora bricks industries, Porora, P.O.Mattannur K.Jose George, Sampath 40 Keezhallur Stone Crushing unit, Velliyamparambu Mary Jose, Sampath Stone Crusher & Hollow bricks, 41 Keezhallur Velliyamparambu, Mattannur M/S Santhi Stone Crusher, 44 Chavesseri 19 th mile 19 th mile, Chavassery, Mattannur © Department of Mining and Geology, Government of Kerala. 1 Code Village Locality Owner Firm Operator M/S Conical Hollow bricks 45 Chavesseri Parambil industries, Chavassery, Mattannur Jaya Metals, 46 Keezhur Uliyil Choothuvepumpara K.P.Sathar, Blue Diamond Vellayamparamb 47 Keezhallur Granite Industries, u Velliyamparambu M/S Classic Stone Crusher 48 Keezhallur Vellay & Hollow Bricks Industries, Vellayamparambu C.Laxmanan, Uthara Stone 49 Koodali Vellaparambu Crusher, Vellaparambu Fivestar Stone Crusher & Hollow Bricks, 50 Keezhur Keezhurkunnu Keezhurkunnu, Keezhur P.O. -

Sheet1 Page 1 Work Experience Fair (On the Spot) Reg. No Code No

Sheet1 Work Experience Fair (On the Spot) Category : HSS/VHSS 320 - Agarbathi Making Reg. No Code No. Name STD School Name Grade Marks Kadachira High School ( Kannur 2961 V07A8 SHINSARAJ C 11 A 255 South ) 4293 V07C4 SIDHARTH. C.K 12 Sivapuram HS ( Mattannur ) A 250 KKV MEMMORIAL PANOOR 7176 V07C1 NEHA K P 12 A 246 HSS ( Panoor ) St.Cornelius HS Kolayad 3490 V07B9 ANUSREE KR 11 A 240 ( Kuthuparamba ) 4292 V07B8 JEENA DAS 12 GHSS Mambaram ( Mattannur ) A 240 3963 V07A4 SOORYA.A.C 12 GBVHSS MADAYI ( Madayi ) A 231 Govt.Higher Secondary School 4767 V07B3 ASHIGA K P 11 A 228 Ramanthally ( Payyannur ) Mambaram HSS ( Thalassery 6210 V07C5 ABHINAV P 11 A 226 North ) Govt.H.S.S. Chala ( Kannur 2576 V07A9 SREERAG SURESH 11 A 223 North ) P.R MEMORIAL 7177 V07C2 RIJIL.K.K 12 A 218 KOLAVALLUR HSS ( Panoor ) AISWARYA St.Teresa`S A.I.H.S.S.Kannur 2575 V07A1 12 A 218 BHARGAVAN.K ( Kannur North ) Govt.Brennen HSS Thalassery 5204 V07B6 THEERTHA K. 12 A 215 ( Thalassery South ) BVJMHS Perumbadavu 7354 V07A6 NIRMAL K JOSE 11 A 212 ( Thalparamba North ) AVS Govt.Higher Secondary 4768 V07B4 JASNA PV 11 School B 205 Karivellur ( Payyannur ) 2058 V07C3 NIKHILESH M 12 Iritty High School ( Iritty ) B 202 Govt. H.S.S Chundangapoil 6209 V07B7 SWARAG 11 B 185 ( Thalassery North ) 1625 V07B1 KHADIJATHUL IJAJA 11 G.H.S.S. Irikkur ( Irikur ) B 184 GHSS KANIYANCHAL 7353 V07A5 SEETHU SURENDRAN 11 C 155 ( Thalparamba North ) GVHSS Thottada ( Kannur 2962 V07B5 RIJIN K V 11 145 South ) 321 - Bamboo Products Page 1 Sheet1 Reg. -

District Survey Report of Minor Minerals (Except River Sand)

GOVERNMENT OF KERALA DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT OF MINOR MINERALS (EXCEPT RIVER SAND) Prepared as per Environment Impact Assessment (EIA) Notification, 2006 issued under Environment (Protection) Act 1986 by DEPARTMENT OF MINING AND GEOLOGY www.dmg.kerala.gov.in November, 2016 Thiruvananthapuram Table of Contents Page no. 1 Introduction ............................................................................................................................... 3 2 Administration ........................................................................................................................... 3 3 Drainage and Irrigation .............................................................................................................. 3 4 Rainfall and climate.................................................................................................................... 4 5 Other meteorological parameters ............................................................................................. 6 5.1 Temperature .......................................................................................................................... 6 5.2 Relative Humidity ................................................................................................................... 6 5.3 Evaporation ............................................................................................................................ 6 5.4 Sunshine Hours ..................................................................................................................... -

The Chirakkal Dynasty: Readings Through History

THE CHIRAKKAL DYNASTY: READINGS THROUGH HISTORY Kolathunadu is regarded as one of the old political dynasties in India and was ruled by the Kolathiris. The Mushaka vamsam and the kings were regarded as the ancestors of the Kolathiris. It was mentioned in the Mooshika Vamsa (1980) that the boundary of Mooshaka kingdom was from the North of Mangalapuram – Puthupattanam to the Southern boundary of Korappuzha in Kerala. In the long Sanskrit historical poem Mooshaka Vamsam, the dynastic name of the chieftains of north Malabar (Puzhinad) used is Mooshaka (Aiyappan, 1982). In the beginning of the fifth Century A.D., the kingdom of Ezhimala had risen to political prominence in north Kerala under Nannan… With the death of Nannan ended the most glorious period in the history of the Ezhimala Kingdom… a separate line of rulers known as the Mooshaka kings held sway over this area 36 (Kolathunad) with their capital near Mount Eli. It is not clear whether this line of rulers who are celebrated in the Mooshaka vamsa were subordinate to the Chera rulers of Mahodayapuram or whether they ruled as an independent line of kings on their own right (in Menon, 1972). The narration of the Mooshaka Kingdom up to the 12th Century A.D. is mentioned in the Mooshaka vamsa. This is a kavya (poem) composed by Atula, who was the court poet of the King Srikantha of Mooshaka vamsa. By the 14th Century the old Mooshaka kingdom had come to be known as Kolathunad and a new line of rulers known as the Kolathiris (the ‘Colastri’ of European writers) had come into prominence in north Kerala.