Illegal Street Racing and Associated (Hooning) Behaviours

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Illinois Rules of the Road 2021 DSD a 112.35 ROR.Qxp Layout 1 5/5/21 9:45 AM Page 1

DSD A 112.32 Cover 2021.qxp_Layout 1 1/6/21 10:58 AM Page 1 DSD A 112.32 Cover 2021.qxp_Layout 1 5/11/21 2:06 PM Page 3 Illinois continues to be a national leader in traffic safety. Over the last decade, traffic fatalities in our state have declined significantly. This is due in large part to innovative efforts to combat drunk and distracted driving, as well as stronger guidelines for new teen drivers. The driving public’s increased awareness and avoidance of hazardous driving behaviors are critical for Illinois to see a further decline in traffic fatalities. Beginning May 3, 2023, the federal government will require your driver’s license or ID card (DL/ID) to be REAL ID compliant for use as identification to board domestic flights. Not every person needs a REAL ID card, which is why we offer you a choice. You decide if you need a REAL ID or standard DL/ID. More information is available on the following pages. The application process for a REAL ID-compliant DL/ID requires enhanced security measures that meet mandated federal guidelines. As a result, you must provide documentation confirming your identity, Social Security number, residency and signature. Please note there is no immediate need to apply for a REAL ID- compliant DL/ID. Current Illinois DL/IDs will be accepted to board domestic flights until May 3, 2023. For more information about the REAL ID program, visit REALID.ilsos.gov or call 833-503-4074. As Secretary of State, I will continue to maintain the highest standards when it comes to traffic safety and public service in Illinois. -

San Diegd Police Department San Diego, California

03-35 SAN DIEGD POLICE DEPARTMENT SAN DIEGO, CALIFORNIA C/5 C 3 5 Project Summary: Drag-Net San Diego Police Department The Problem: Illegal motor vehicle speed contests, commonly known as street races, throughout the City of San Diego. Analysis: Officers developed a knowledge of the street-racing culture through undercover investigations, interviews with officers who had experience dealing with racers, monitoring Internet websites, interviewing racers, and exploring the legal alternatives that are available. Officers studied data on calls for service, traffic collisions, arrests, and citations related to illegal speed contests. Officers established baseline figures to determine the size of the problem. They identified collateral crimes that were occurring because of the problem. The officers set goals of reducing incidents of street racing to a level that it could be managed with existing resources and to reduce the number of illegally modified vehicles on the roadways. The most important analysis the officers made was whether they could impact the problem, despite its magnitude and history of indifference by society. They realized they had to change society's paradigm about street racing. The Drag-Net Officers decided they would only be successful if they truly made San Diego a safer place. They knew lives could be saved if their analysis was accurate, and the response was effective. Response: Officers used a multi-faceted approach in a comprehensive response strategy: • Undercover operations to identify, apprehend, and prosecute racers -

Frustration, Aggression & Road Rage

Always remember that the primary goal in defensive driving is to stay safe and live to drive another day. Frustration, Aggression The context in which frustration occurs Other road users are probably equally and Road Rage can determine both the nature and extent frustrated in traffic, perhaps more so. of our own resulting aggressive behavior. They may not be as prepared for traffic. There are also differences in people’s nat- Frustration occurs when someone or Be courteous and forgiving. Your ural propensities. Some drivers are something impedes your progress toward behavior may serve to reduce their content to mutter curses to themselves a goal. In the driving environment our goal levels of frustration and consequently while others are provoked to physical is to get to our destination as quickly and their levels of aggression and violence. Both personal attributes and as safely as possible. When other road risk-taking, thereby making the traffic situational factors can moderate our users interfere with our progress we environment safer for everyone, aggressive responses. become frustrated. In the driving environ- including you. ment, increases in aggression can have Some experts distinguish between Do not fret over people, conditions and deadly consequences. Frustration can aggressive driving and road rage. things that you cannot control. Choose lead to any or all of the following Aggressive driving is instrumental, that is, your battles wisely and save your aggressive behaviour: it serves to further progress toward a energy and emotions for situations that desired outcome when we are frustrated. Excessive speeding or street racing you can influence. -

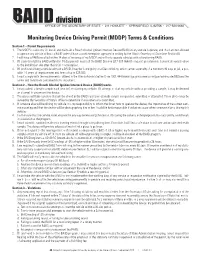

Monitoring Device Driving Permit (MDDP) Terms & Conditions

division OFFICE OF THE SECRETARY OF STATE • 211 HOWLETT • SPRINGFIELD, IL 62756 • 217-524-0660 Monitoring Device Driving Permit (MDDP) Terms & Conditions Section 1 – Permit Requirements 1. The MDDP is valid only if I install and maintain a Breath Alcohol Ignition Interlock Device (BAIID) in any vehicle I operate, and that I am not allowed to operate any vehicle without a BAIID unless I have a work exemption approved in writing by the Illinois Secretary of State (see Section 8). 2. I will have a BAIID installed within 14 days of issuance of my MDDP and will only operate vehicles with a functioning BAIID. 3. If I cannot install the BAIID within the 14-day period I must call the BAIID Division (217-524-0660) to request an extension. I am not allowed to drive to the installation site after the initial 14-day period. 4. If I am found driving a vehicle without a BAIID, I may be found guilty of a Class 4 felony, which carries a penalty of a minimum 30 days in jail, a pos- sible 1-3 years of imprisonment and fines of up to $25,000. 5. I must comply with the requirements outlined in the Illinois Administrative Code 1001.444 (www.ilga.gov/commission/jcar/admincode/092) and the Terms and Conditions contained in this document. Section 2 – How the Breath Alcohol Ignition Interlock Device (BAIID) works 1. I must submit a breath sample each time before starting my vehicle. If I attempt to start my vehicle without providing a sample, it may be deemed an attempt to circumvent the device. -

Road Safety Impact of Ontario Street Racing and Stunt Driving Law

Accident Analysis and Prevention 71 (2014) 72–81 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Accident Analysis and Prevention jou rnal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/aap Road safety impact of Ontario street racing and stunt driving law a a,b,∗ c d Aizhan Meirambayeva , Evelyn Vingilis , A. Ian McLeod , Yoassry Elzohairy , c a c Jinkun Xiao , Guangyong Zou , Yuanhao Lai a Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry, The University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada b Population and Community Health Unit, Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry, The University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada c Department of Statistical and Actuarial Sciences, The University of Western Ontario, London, Ontario, Canada d Ministry of Transportation of Ontario, Toronto, Ontario, Canada a r t i c l e i n f o a b s t r a c t Article history: Objective: The purpose of this study was to conduct a process and outcome evaluation of the deterrent Received 5 December 2013 impact of Ontario’s street racing and stunt driving legislation which came into effect on September 30, Received in revised form 5 May 2014 2007, on collision casualties defined as injuries and fatalities. It was hypothesized that because males, Accepted 13 May 2014 especially young ones, are much more likely to engage in speeding, street racing and stunt driving, the new Available online 2 June 2014 law would have more impact in reducing speeding-related collision casualties in males when compared to females. Keywords: Methods: Interrupted -

Part Three - Traffic Code

PART THREE - TRAFFIC CODE TITLE ONE - Administration, Enforcement and Penalties Chapter 301 Definitions Chapter 303 Enforcement; Impounding Chapter 305 Traffic Control Chapter 307 Traffic Control Map and File Chapter 309 Penalties TITLE THREE - Public Ways and Traffic Control Devices Chapter 311 Obstruction and Special Uses of Public Ways Chapter 313 Traffic Control Devices TITLE FIVE - Vehicles and Operation Chapter 331 Operation Generally Chapter 333 DWI; Reckless Operation; Speed Chapter 335 Licensing; Accidents Chapter 337 Safety and Equipment Chapter 339 Commercial and Heavy Vehicles Chapter 341 Drivers of Commercial Cars or Tractors Chapter 343 [Reserved] Chapter 345 Noise Emission From Motor Vehicles TITLE SEVEN - Parking Chapter 351 Parking Generally Chapter 353 Parking Meters TITLE NINE - Pedestrians, Bicycles, Motorcycles and Snowmobiles Chapter 371 Pedestrians Chapter 373 Bicycles and Motorcycles Chapter 375 Bicycle Licensing (REPEALED 11-22-2010; Ord. 2010-108) Chapter 377 Snowmobiles and All Purpose Vehicles PART THREE - TRAFFIC CODE TITLE ONE - Administration, Enforcement and Penalties Chapter 301 Definitions Chapter 303 Enforcement; Impounding Chapter 305 Traffic Control Chapter 307 Traffic Control Map and File Chapter 309 Penalties CHAPTER 301: DEFINITIONS Section 301.01 Meaning of words and phrases 301.02 Agricultural tractor 301.03 Alley 301.04 Bicycle 301.05 Bus 301.06 Business district; Downtown business district 301.07 Commercial tractor 301.08 Controlled-access highway 301.09 Crosswalk 301.10 Driver or operator 301.11 -

Northern Territory Law Journal

NORTHERN TERRITORY LAW JOURNAL Volume 3, Number 2 September 2016 ARTICLES Ethics and etiquette – Justice Graham Hiley RFD and Kate Bulling Expanding on the presentation given by the Hon Justice Graham Hiley at the 2015 Criminal Lawyers Association of the Northern Territory Conference, this article provides both newly admitted and more experienced practitioners with a sound basis for understanding the origins and sources of legal ethics and the potential consequences for practitioners who fall foul of their duties. ................................. 59 The right to silence – David Morters This article considers the meaning of the concept, its historical origins and development in the case law, the arguments for and against modification and the effectiveness of changes that have been introduced in England and New South Wales. Finally, it expresses a conclusion about how best the balance can be struck between the interests of the individual and the state on this much debated topic. ........................................................................................................ 77 Driving whilst disqualified – A case for change – Julian R Murphy and Hugo Moodie This article highlights the authors’ concern at the approach of Northern Territory courts to sentencing for the offence of driving whilst disqualified. Particular concern is expressed at the impact on Indigenous Territorians. It is posited that this approach rests on an unstable precedential foundation, lacks cogent justification in sentencing principles and is an inefficacious -

Teen Driving Laws

Info for Parents, Teen Drivers and Their Passengers With tighter restrictions on teen drivers and the • Distracted Driving: It is against the law for Passenger Restrictions For All Learner’s Permit and 16- and need for them and their passengers to be safe, teens to drive distracted as well as use any For the entire time a driver holds a learner’s permit, below are some important reminders for teens, mobile electronic devices while driving. he or she may not have any passengers except 17-Year-Old Licensed Drivers for either: parents, passengers and their communities: • Purposeful Driving: Parents need to • A licensed driving instructor giving instruction They may NOT: continuously monitor and guide their teenagers’ • Transport more passengers than the number driving activity, and limit their travel to and others accompanying that instructor. Managing The Driving Experience • One person who is providing instruction and is of seatbelts in the vehicle. purposeful driving. Once teens begin to engage • Operate any vehicle that requires a public • Crashes Kill Teens: Motor vehicle crashes in joy-riding, their crash-risk increases at least 20 years old, has held a driver’s license are the #1 cause of death for 15-19 year- for four or more consecutive years and whose passenger transportation permit or a vanpool dramatically, and more so with each additional vehicle. old teenagers. teenage passenger. license has not been suspended during the four years prior to training. Parents or legal guardian • Use a cell phone (even if it is hands-free) or • Brain Development: Research shows that the • Health Care Professionals: Pediatricians, family may accompany the instructor. -

Street Racing Enforcement and Illegal Emission Modifications -Expanded Course Outline

San Jose Police Department Street Racing Enforcement and Illegal Emission Modifications -Expanded Course Outline- I. Registration A. SJPD Administrative record keeping B. POST administrative record keeping II. DragNet Program History A. Office of Traffic Safety Grant 1. Accidents related to racing 2. Funding of program 3. Successes and failures B. Education aspects of Dragnet program 1. Class educational goals 2. DragNet spreading throughout the area 3. Handouts 4. Copyrights C. Enforcement aspects of Dragnet program 1. Operations 2. Multi agency collaborations 3. 24/7 emission enforcement III. Principles of Traffic Law A. Recognize basic Vehicle Code requirements related to vehicle body modifications 1. Fins 2. Air dams 3. Fenders B. Recognize legal vehicle modifications 1. Tachometer 2. Seats 3. Seatbelts 4. Stickers C. Recognize violations related to vehicle exhaust systems 1. Exhaust tips 2. Baffles 3. Decibels 4. Excessive or unusual noise 1 03/14/2018 D. Recognize violations related to vehicle modifications 1. Lights 2. Window tinting 3. Vehicle height 4. View obstructions E. Recognize violations related to illegal emissions 1. 27156b California Vehicle Code (CVC) 2. Stock motors 3. Show racers 4. Serious racers 5. Common modifications a. Open air elements b. Headers c. Colored tubing d. Camshaft gears e. Fuel pressure regulator f. Other associated modifications F. Recognize legal modifications accompanied by a Bureau of Automotive Repair (BAR) sticker (Referee Label) 1. Location 2. Type of sticker 3. Description of what is to be on the sticker G. Executive Order numbers 1. Character layout 2. California Air Resources Board (CARB) items H. Computers 1. Placement 2. Capabilities 3. -

O-Caravanning-Ordinance

1 ORDINANCE NO. _______________ 2 3 AN ORDINANCE TO PROHIBIT VEHICULAR TRESPASS, THE 4 CARAVANNING OF VEHICLES, AND DRAG RACING WITHIN THE 5 CITY OF LITTLE ROCK, ARKANSAS; AND FOR OTHER PURPOSES. 6 7 WHEREAS, the City of Little Rock, Arkansas, has an interest in maintaining the health, safety, and 8 welfare of the City’s residents; and, 9 WHEREAS, there has been a significant increase in street racing and reckless driving exhibitions both 10 in business parking lots and on public streets; and, 11 WHEREAS, such activities are an immediate threat to the public safety and disrupt the public peace; 12 and, 13 WHEREAS, City of Little Rock Mayor Frank Scott, Jr., in his Declaration of Local Disaster 14 Emergency 20-02 on April 6, 2020, which amended the Little Rock Executive Orders of March 12, 2020, 15 and March 26, 2020, that prohibited caravanning; and, 16 WHEREAS, City of Little Rock Mayor Frank Scott, Jr., in his Declaration of Local Disaster 17 Emergency 20-08 on December 29, 2020, which amended the Little Rock Executive Orders of August 21, 18 2020, that prohibited caravanning and drag racing; and, 19 WHEREAS, pursuant to Arkansas Code Annotated § 14-54-103 the City has the power to prevent 20 injury or annoyance within the limits of the municipal corporation from anything dangerous, offensive, or 21 unhealthy; and, 22 WHEREAS, pursuant to Arkansas Code Annotated § 14-54-103 the City is specifically authorized to 23 regulate and prohibit processions or assemblages on City streets; and, 24 WHEREAS, pursuant to Arkansas Code Annotated § 27-49-106 the City may adopt traffic regulations, 25 in addition to those already adopted by the State, provided there is no conflict with the State Statutes. -

Utah's Street Racing Law

Utah's Street Racing Law Note: The following is a summary of Utah laws that apply to street racing. Other laws may apply in any street racing incident, including other traffic violations, based on the specific circumstances of the incident. Current law 41-6a-606. Speed contest or exhibition on highway -- Barricade or obstruction. (1) A person may not: (a) engage in any motor vehicle speed contest or exhibition of speed on a highway; or (b) aid or abet in any motor vehicle speed contest or exhibition on any highway. (2) A person may not, in any manner, obstruct or place any barricade or obstruction or assist or participate in placing any barricade or obstruction upon any highway for any purpose prohibited under Subsection (1). Penalties • Class C misdemeanor - a violator may be: < imprisoned for a term not exceeding 90 days ( Sec. 76-3-204); and < sentenced to pay a fine not exceeding $750 (Sec. 76-3-301). • The current fines recommended by the Judicial Council are: < $107 ($82 in juvenile court) for exhibition driving; and < $232 ($142 in juvenile court) for a speed contest. • A mandatory court appearance is required for engaging in a speed contest. • Driver License Sanctions: < Points are assessed against the person's driver license, and if the driver exceeds certain point totals, the driver is put on probation or the driver's license is suspended for a certain period of time. Other street racing violations • Reckless driving - a driver must operate a vehicle in a willful or wanton disregard for the safety of persons or property or commit three or more traffic violations in a series of acts within a single continuous period of driving (Sec. -

Crime Problem'' of the Northern Territory Intervention

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Analysis and Policy Observatory (APO) Addressing the “crime problem’’ of the Northern Territory Intervention: alternate paths to regulating minor driving offences in remote Indigenous communities Dr Thalia Anthony Dr Harry Blagg Report to the Criminology Research Advisory Council Grant: CRG 38/09-10 June 2012 1 This is a project supported by a grant from the Criminology Research Grants. The views expressed are the responsibility of the author and are not necessarily those of the Council. TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................ 5 Background ......................................................................................................................................... 5 Methodology ....................................................................................................................................... 6 Quantitative findings .......................................................................................................................... 7 Qualitative findings ............................................................................................................................. 7 Key Recommendations ....................................................................................................................... 8 RATIONALE AND AIMS OF STUDY ........................................................................................................