1 the Ensemblist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FY14 Tappin' Study Guide

Student Matinee Series Maurice Hines is Tappin’ Thru Life Study Guide Created by Miller Grove High School Drama Class of Joyce Scott As part of the Alliance Theatre Institute for Educators and Teaching Artists’ Dramaturgy by Students Under the guidance of Teaching Artist Barry Stewart Mann Maurice Hines is Tappin’ Thru Life was produced at the Arena Theatre in Washington, DC, from Nov. 15 to Dec. 29, 2013 The Alliance Theatre Production runs from April 2 to May 4, 2014 The production will travel to Beverly Hills, California from May 9-24, 2014, and to the Cleveland Playhouse from May 30 to June 29, 2014. Reviews Keith Loria, on theatermania.com, called the show “a tender glimpse into the Hineses’ rise to fame and a touching tribute to a brother.” Benjamin Tomchik wrote in Broadway World, that the show “seems determined not only to love the audience, but to entertain them, and it succeeds at doing just that! While Tappin' Thru Life does have some flaws, it's hard to find anyone who isn't won over by Hines showmanship, humor, timing and above all else, talent.” In The Washington Post, Nelson Pressley wrote, “’Tappin’ is basically a breezy, personable concert. The show doesn’t flinch from hard-core nostalgia; the heart-on-his-sleeve Hines is too sentimental for that. It’s frankly schmaltzy, and it’s barely written — it zips through selected moments of Hines’s life, creating a mood more than telling a story. it’s a pleasure to be in the company of a shameless, ebullient vaudeville heart.” Maurice Hines Is . -

July 14–19, 2019 on the Campus of Belmont University at Austin Peay State University

July 14–19, 2019 On the Campus of Belmont University at Austin Peay State University OVER 30 years as Tennessee’s only Center of Excellence for the Creative Arts OVER 100 events per year OVER 85 acclaimed guest artists per year Masterclasses Publications Performances Exhibits Lectures Readings Community Classes Professional Learning for Educators School Field Trip Grants Student Scholarships Learn more about us at: Austin Peay State University does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion, creed, national origin, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity/expression, disability, age, status as a protected veteran, genetic information, or any other legally protected class with respect to all employment, programs and activities sponsored by APSU. The Premier Summer Teacher Training Institute for K–12 Arts Education The Tennessee Arts Academy is a project of the Tennessee Department of Education and is funded under a grant contract with the State of Tennessee. Major corporate, organizational, and individual funding support for the Tennessee Arts Academy is generously provided by: Significant sponsorship, scholarship, and event support is generously provided by the Belmont University Department of Art; Community Foundation of Middle Tennessee; Dorothy Gillespie Foundation; Solie Fott; Bobby Jean Frost; KHS America; Sara Savell; Lee Stites; Tennessee Book Company; The Big Payback; Theatrical Rights Worldwide; and Adolph Thornton Jr., aka Young Dolph. Welcome From the Governor of Tennessee Dear Educators, On behalf of the great State of Tennessee, it is my honor to welcome you to the 2019 Tennessee Arts Academy. We are so fortunate as a state to have a nationally recognized program for professional development in arts education. -

<I>Spring Awakening</I>

The Journal of American Drama and Theatre (JADT) https://jadtjournal.org Silence, Gesture, and Deaf Identity in Deaf West Theatre's Spring Awakening by Stephanie Lim The Journal of American Drama and Theatre Volume 33, Number 1 (Fall 2020) ISNN 2376-4236 ©2020 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center For a woman to bear a child, she must . in her own personal way, she must . love her husband. Love him, as she can love only him. Only him . she must love—with her whole . heart. There. Now, you know everything.[1] Frau Bergman, Spring Awakening In the opening scene of Spring Awakening, Wendla begs her mother to explain where babies come from, to which her mother bemoans, “Wendla, child, you cannot imagine—.” In Deaf West Theatre’s version of the show, Frau Bergman speaks this line while bringing her pinky finger up to her head, palm outward, but Wendla quickly corrects the gesture, indicating that her mother has actually inverted the American Sign Language (ASL) for “imagine,” a word signed with palm facing inward.[2] As part of a larger dialogue that closes with the epigraph above, Bergman’s struggle to communicate about sexual intercourse in both ASL and English is one of many exchanges in which adults find themselves unable to communicate effectively with teenagers. The theme of (mis)communication is also evoked through characters’ refusal to communicate with each other at all, as in the musical number “Totally Fucked.” When Melchior’s teachers demand he confess to having authored the obscene 10-page document, “The Art of Sleeping With” (which they claim hastened the suicide of his best friend Moritz), they reject his attempts to explain. -

Edward Albee's at Home at The

CAST OF CHARACTERS TROY KOTSUR*............................................................................................................................PETER Paul Crewes Rachel Fine Artistic Director Managing Director RUSSELL HARVARD*, TYRONE GIORDANO..........................................................................................JERRY AND AMBER ZION*.................................................................................................................................ANN JAKE EBERLE*...............................................................................................................VOICE OF PETER JEFF ALAN-LEE*..............................................................................................................VOICE OF JERRY PAIGE LINDSEY WHITE*........................................................................................................VOICE OF ANN *Indicates a member of Actors’ Equity Association, the Union of David J. Kurs Professional Actors and Stage Managers in the United States. Artistic Director Production of ACT ONE: HOMELIFE ACT TWO: THE ZOO STORY Peter and Ann’s living room; Central Park, New York City. EDWARD ALBEE’S New York City, East Side, Seventies. Sunday. Later that same day. AT HOME AT THE ZOO ADDITIONAL PRODUCTION STAFF STARRING COSTUME AND PROPERTIES REHEARSAL STAGE Jeff Alan-Lee, Jack Eberle, Tyrone Giordano, Russell Harvard, Troy Kotsur, WARDROBE SUPERVISOR SUPERVISOR INTERPRETER COMBAT Paige Lindsey White, Amber Zion Deborah Hartwell Courtney Dusenberry Alek Lev -

Sprawak Release 12-8-14 V1CLEAN.Docx.Docx

WALLIS ANNENBERG CENTER FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS, DEAF WEST THEATRE AND CODY LASSEN PRESENT Spring Awakening Book and Lyrics by STEVEN SATER Music by DUNCAN SHEIK Directed by MICHAEL ARDEN 22 Performances Only! May 21 to June 7, 2015 (Press Opening May 28, 2015) (Beverly Hills, CA – January 7, 2015) Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts (“The Wallis”), Deaf West Theatre and Cody Lassen present the Tony Award-winning musical Spring Awakening for a limited 22-performance engagement Thursday, May 21 to Sunday, June 7, 2015 (press opening May 28) in the Bram Goldsmith Theater. Tickets are now on sale. The innovative and acclaimed production, which enjoyed a sold-out engagement at downtown L.A.’s Rosenthal Theatre in fall 2014, is performed simultaneously in American Sign Language and spoken English by a cast of 25. The Los Angeles Times said that Spring Awakening is “an emotional triumph,” and that “Awakening awakens us to the dormant possibilities of this musical, with all the goose-bumps and teardrops to prove it.” Patricia Wolff, Interim Artistic Director of The Wallis says, “We are thrilled to welcome to The Wallis Los Angeles’ own Tony-winning Deaf West Theatre, and to share the creativity and joyousness of this brilliant and utterly original production with a broader audience. In Spring Awakening, American Sign Language is not just incorporated but actually choreographed into this emotionally charged musical, creating an organic and beautifully theatrical metaphor, ultimately expanding the theme of adolescent struggle to one that also celebrates the universal human need for communication and connection." James D’Asaro, Interim Producing Director of The Wallis noted, “Our role as lead producer for the transfer of Spring Awakening to our venue points to two of our presenting tenets – to not only partner with the best and most creative theaters in this country and abroad, but to support in the fullest sense visionary and innovative work created in our own Los Angeles theatre community. -

Picture As Pdf

1 Cultural Daily Independent Voices, New Perspectives Deaf West’s Rousing Spring Awakening Sylvie Drake · Wednesday, June 3rd, 2015 Arousing all senses. This may be the choice three-word assessment of the stunning Deaf West Theatre production of Spring Awakening that made the leap from a long run at Inner City Arts to the larger Wallis Annenberg Center in Beverly Hills. Whatever the terms of this arrangement, one can only celebrate the fact that it happened and that, in so doing, it imaginatively took advantage of the height and breadth of the Bram Goldsmith space at The Wallis. Simultaneously, one can only weep at the brevity of its presence there. Even with the just-announced extension, the show will close Sunday, June 14. First, some background. Theatre of the deaf is not a new phenomenon, but it is neither a common nor a particularly ancient one. The first American company to successfully combine deaf and hearing actors on stage was The National Theatre of the Deaf (NTD), established in New England in the late 1960s by David Hays, a Broadway set and lighting designer and avid sailor. Hays had never imagined he would be doing that sort of thing at all. Yet after the success of the Broadway production of The Miracle Worker, Anne Bancroft and Arthur Penn, who had seen from the inside out the effect of the Helen Keller story on general audiences, enticed Hays to get involved in an experiment to do just that. Once inducted, Hays became so enthralled with the concept that he described theatre of the deaf (correctly) as “a major dimensional form of poetry.” He went on to lead the NTD for the next 30 years. -

Bellamie Bachleda Bellamie Bachleda Is a Creative Talent Who Has Been Writing, Directing and Acting for Over Ten Years

Bellamie Bachleda Bellamie Bachleda is a creative talent who has been writing, directing and acting for over ten years. She worked in numerous video and film productions and taught drama and storytelling workshops and classes at the schools, camps, and festivals. In 2017, she and a group of splendid #deaftalent co-founded a non-profit theatre company, Deaf Austin Theatre, where she is currently a co-artistic director. Michelle A. Banks Michelle A. Banks, a native of Washington, DC, is an award-winning actress, writer, director, producer, choreographer, motivational speaker, and teacher. After Michelle received her Bachelor of Arts degree in Drama Studies from the State University of New York at Purchase, she founded Onyx Theatre Company in New York City, the first deaf theatre company in the United States for people of color. Her work with Onyx for eleven years earned the Cultural Enrichment Award from Gallaudet University and the Distinguished Service Award from New York Deaf Theatre. Michelle’s most recent producing/directing credits: Gallaudet University’s A Raisin in the Sun, Look Through My Eyes, Silent Scream, Z: A Christmas Story, What It’s Like? (One Man Show) and In Sight and Sound: De(A)F Poetry I, II, & III. Her acting appearances include Sole, The C.A. Lyons Project, Soul Food, Girlfriends, and Big River. Received the Laurent Clerc Award from Gallaudet University in 2017. Fred Michael Beam Fred Michael Beam is the outreach coordinator for Sunshine 2.0. He is an experienced performer with acting credits that include Nicholas in By the Music of the Spheres at the Goodman Theater, Harry in Harry the Dirty Dog at the Bethesda Academy of Performing Arts; Witness in Miracle Workers and Stranger in Mad Dancer at the Arena Stage in Washington, DC; Fall Out Shelter, The Dirt Maker, and The Underachiever at the Kennedy Center; the title character in Othello at Gallaudet University; and Steve in A Streetcar Named Desire at SignRise Cultural Arts in Washington, DC. -

Merrily We Roll Along BRENT SCHINDELE*

CAST OF CHARACTERS AARON LAZAR*...................................................................FRANKLIN SHEPARD Paul Crewes Rachel Fine Artistic Director Managing Director DONNA VIVINO*.............................................................................MARY FLYNN AND WAYNE BRADY*.....................................................................CHARLEY KRINGAS Cody Lassen AMIR TALAI*............................................................................JOE JOSEPHSON in association with Robert Laurita, Aaron Sanko, Invisible Wall Productions/ Diego Kolankowsky, Kari Lynn Hearn WHITNEY BASHOR*.....................................................................BETH SPENCER PRODUCTION OF SAYCON SENGBLOH*................................................................GUSSIE CARNEGIE MAXIMUS BRANDON VERSO................................................................FRANK JR. KEVIN PATRICK DOHERTY*.........................................................................TYLER Merrily We Roll Along BRENT SCHINDELE*................................................................................TERRY ERIC B. ANTHONY*................................................................................SCOTTY MUSIC AND LYRICS BOOK BY LAURA DICKINSON*..................................................................................DORY Stephen Sondheim George Furth SANDY BAINUM*..........................................................................................RU JENNIFER FOSTER*........................................................................BARTENDER -

Casting, Stigma, and Difference in Broadway Musicals Since "A Chorus Line" (1975)

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 5-2019 Broadway Bodies: Casting, Stigma, and Difference in Broadway Musicals Since "A Chorus Line" (1975) Ryan Donovan The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/3084 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] BROADWAY BODIES: CASTING, STIGMA, AND DIFFERENCE IN BROADWAY MUSICALS SINCE A CHORUS LINE (1975) by RYAN DONOVAN A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Theatre and Performance in partiaL fulfiLLment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of PhiLosophy, The City University of New York 2019 © 2019 RYAN DONOVAN ALL Rights Reserved ii Broadway Bodies: Casting, Stigma, and Difference in Broadway MusicaLs Since A Chorus Line (1975) by Ryan Donovan This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Theatre and Performance in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of PhiLosophy. ________________ ______________________________________ Date David Savran Chair of Examining Committee ________________ ______________________________________ Date Peter EckersaLL Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Jean Graham-Jones ELizabeth WolLman THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Broadway Bodies: Casting, Stigma, and Difference in Broadway MusicaLs Since A Chorus Line (1975) by Ryan Donovan Advisor: David Savran “You’re not fat enough to be our fat girl.” “Dance like a man.” “Deaf people in a musicaL!?” These three statements expose how the casting process for Broadway musicaLs depends upon making aesthetic disquaLifications. -

Balancing the Theatre-Going Experience for Deaf and Hearing Audiences

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE The Aesthetics of Deaf West Theatre: Balancing the Theatre-Going Experience for Deaf and Hearing Audiences A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of the Arts in Theatre By Brandice Rafus-Brenning May 2018 Copyright by Brandice Rafus-Brenning 2018 ii The thesis of Brandice Rafus-Brenning is approved: ____________________________________ ____________________ Kari Hayter, MFA Date ____________________________________ ____________________ Dr. Lissa Stapleton Date ____________________________________ ____________________ Dr. Hillary Miller, Chair Date California State University, Northridge iii Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to acknowledge and thank Deaf West Theatre for their incredible work. You inspired me to write this thesis and I look forward to enjoying your productions for many years to come. I would also like to acknowledge and express my gratitude for Kanta Kochhar-Lindgren’s theories and insightful research. Eboni, my amazing wife- Thank you for being my biggest supporter and sticking with me through the rollercoaster that is graduate school. Lastly, I would like to thank my committee for their support, insights, and assistance during this process. As well, my fellow graduate students – Thank you for the much- needed moments of levity and for being my sounding boards throughout this challenging process. iv Dedication For Eboni Rafus-Brenning My love, my wife, my best friend, and my favorite proof-reader. Thank you for all that -

Gestural Economies and Production Pedagogies in Deaf West's <Italic

CriticalActs Fantasy on the Clock The Virtual Cruelty of Collected Works’ The Balcony Rebecca Chaleff The first time I saw Collected Works’ produc- both the raw and restored spaces to stage the tion of Jean Genet’s The Balcony (1956) was the polarities of wealth, power, poverty, and despair first time I set foot in San Francisco’s iconic enacted by the characters of The Balcony. Before Old Mint. It was 14 February 2015; wander- the production begins, the audience is allowed ing the halls, I saw traces of history in cubes to roam the smaller rooms of the basement. of glass, maps of memories I did not know, As we wander, we are surrounded by stone and and pictures of a city so demolished by the concrete, ensconced in the secretive chambers 1906 earthquake that I could not recognize it. of Madame Irma’s brothel. In the basement, I discovered deeper remnants Amidst this history, glimpses of the set are of that history in the marks that millions of visible to the audience: white fabric hanging pieces of gold had imprinted against the stone from the ceiling of one room; cords of yarn walls. There, where the stone gave way to the gradual and persistent pressures of coins, I began to imag- ine how Collected Works’ immer- sive production of The Balcony might begin. Today, the Old Mint stands as a massive, stone emblem of history in San Francisco’s Civic Center dis- trict. Although the San Francisco Museum and Historical Society originally planned to convert the landmark into a museum, their plan was terminated before full resto- rations were complete. -

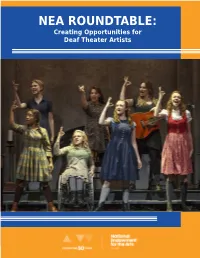

NEA ROUNDTABLE: Creating Opportunities for Deaf Theater Artists

NEA ROUNDTABLE: Creating Opportunities for Deaf Theater Artists NEA ROUNDTABLE: Creating Opportunities for Deaf Theater Artists By Martha Wade Steketee A report from the NEA Roundtable held January 20, 2016, at The Lark in New York City Report on NEA Roundtable on Opportunities for Deaf Theater Artists May 2016 Produced by the NEA Beth Bienvenu, Accessibility Director Greg Reiner, Theater and Musical Theater Director Editorial Assistance by Rebecca Sutton Designed by Kelli Rogowski Steering Committee Michelle Banks, Mianba Productions John Clinton Eisner, The Lark, Artistic Director Tyrone Giordano, dog & pony dc and Gallaudet University DJ Kurs, Deaf West Theatre Julia Levy, Roundabout Theatre, Executive Director Bill O’Brien, Senior Advisor for Innovation to the Chairman Written by Martha Wade Steketee and edited by Jamie Gahlon, Senior Creative Producer, HowlRound | www.howlround.com The Roundtable, January 20, 2016, was hosted by National Endowment for the Arts The Lark, New York City A note regarding terminology and the use of Deaf vs. deaf in this report: Regarding the d/Deaf distinction, the rules are ever-evolving. Ideally, you would defer to whatever someone identifies as, and the markers are varied. There are general rules for usage: whenever referring to a person’s identity, community, or culture, especially in connection with sign language, use the capitalized form, “Deaf.” This capitalization has historically been used to emphasize the Deaf identity, a source of pride, and is distinct from the socially constructed pathological diagnosis of “deafness,” which carries stigma. Whenever referring to hearing status, you will use “deaf.” To further complicate things, there is no solid demarcation for where the capitalized marker “Deaf” came to be.