Balancing the Theatre-Going Experience for Deaf and Hearing Audiences

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FY14 Tappin' Study Guide

Student Matinee Series Maurice Hines is Tappin’ Thru Life Study Guide Created by Miller Grove High School Drama Class of Joyce Scott As part of the Alliance Theatre Institute for Educators and Teaching Artists’ Dramaturgy by Students Under the guidance of Teaching Artist Barry Stewart Mann Maurice Hines is Tappin’ Thru Life was produced at the Arena Theatre in Washington, DC, from Nov. 15 to Dec. 29, 2013 The Alliance Theatre Production runs from April 2 to May 4, 2014 The production will travel to Beverly Hills, California from May 9-24, 2014, and to the Cleveland Playhouse from May 30 to June 29, 2014. Reviews Keith Loria, on theatermania.com, called the show “a tender glimpse into the Hineses’ rise to fame and a touching tribute to a brother.” Benjamin Tomchik wrote in Broadway World, that the show “seems determined not only to love the audience, but to entertain them, and it succeeds at doing just that! While Tappin' Thru Life does have some flaws, it's hard to find anyone who isn't won over by Hines showmanship, humor, timing and above all else, talent.” In The Washington Post, Nelson Pressley wrote, “’Tappin’ is basically a breezy, personable concert. The show doesn’t flinch from hard-core nostalgia; the heart-on-his-sleeve Hines is too sentimental for that. It’s frankly schmaltzy, and it’s barely written — it zips through selected moments of Hines’s life, creating a mood more than telling a story. it’s a pleasure to be in the company of a shameless, ebullient vaudeville heart.” Maurice Hines Is . -

Broadway Patina Miller Leads a (Mostly) Un-Hollywood Lineup of Stellar Stage Nominees

05.23.13 • backstage.com The Tonys return to Broadway Patina Miller leads a (mostly) un-Hollywood lineup of stellar stage nominees wHo will win—and wHo sHould 0523 COV.indd 1 5/21/13 12:26 PM Be the Master Storyteller Learn to engage in the truth of a story, breathe life into characters, and create powerful moments on camera. Welcome to your craft. acting for film & television Vancouver Film School pureacting.com Vancouver Film Sch_0321_FP.indd 1 3/18/13 11:00 AM CONTENTS vol. 54, no. 21 | 05.23.13 CENTER STAGE COVER STORY Flying High 1 8 s inging, acting, dancing, and trapeze! Patina Miller secures her spot as one of Broadway’s best with her tony-nominated multi- hyphenate performance in “Pippin” FEATURES 17 2013 tony awards 22 smackdown who will—and who should— UPSTAGE take home the tony on June 9 Col a NEWS : Ni 05 take Five hair ipka what to see and where to go r in the week ahead ith DOWNSTAGE D : Ju griffith; 07 top news CASTING D Looking ahead at the 2013–14 27 new York tristate ewelry tv season Notices audition highlights heia; J 08 stage t : the Drama League opens 39 california Ng a new theater center Notices lothi in downtown Manhattan audition highlights illey;Miller: photo: Cha l ayes; C ayes; 10 screen 43 national/regional h ouise l 72 hour shootout 18 Notices gives opportunities audition highlights arah arah s to asian-americans : Chelsea CHARTS ACTOR 101 54 production stylist ; 13 Inside Job L.a.: feature films: N Dogfish accelerator upcoming co-founders James Belfer n.Y.: feature films: k salo ; lilley: Courtesy C N and Michelle soffen upcoming so N 14 the working actor 55 cast away a robi Dealing with unprofessional hey, Beantown! for roy teelu NiN co-stars D MEMBER SPOTLIGHT har C 16 secret agent Man 56 sarah Louise Lilley rit p why you could still lose your “i was once told that my roles ai k pilot job have a theme in common— : characters that are torn oftware; Dogfish: s akeup 17 tech & dIY between two choices, snapseed whether it be two worlds, two e; M N men, two cultures, or two cover photo: chad griffith personalities. -

Syndication's Sitcoms: Engaging Young Adults

Syndication’s Sitcoms: Engaging Young Adults An E-Score Analysis of Awareness and Affinity Among Adults 18-34 March 2007 BEHAVIORAL EMOTIONAL “Engagement happens inside the consumer” Joseph Plummer, Ph.D. Chief Research Officer The ARF Young Adults Have An Emotional Bond With The Stars Of Syndication’s Sitcoms • Personalities connect with their audience • Sitcoms evoke a wide range of emotions • Positive emotions make for positive associations 3 SNTA Partnered With E-Score To Measure Viewers’ Emotional Bonds • 3,000+ celebrity database • 1,100 respondents per celebrity • 46 personality attributes • Conducted weekly • Fielded in 2006 and 2007 • Key engagement attributes • Awareness • Affinity • This Report: A18-34 segment, stars of syndicated sitcoms 4 Syndication’s Off-Network Stars: Beloved Household Names Awareness Personality Index Jennifer A niston 390 Courtney Cox-Arquette 344 Sarah Jessica Parker 339 Lisa Kudrow 311 Ashton Kutcher 297 Debra Messing 294 Bernie Mac 287 Matt LeBlanc 266 Ray Romano 262 Damon Wayans 260 Matthew Perry 255 Dav id Schwimme r 239 Ke ls ey Gr amme r 229 Jim Belushi 223 Wilmer Valderrama 205 Kim Cattrall 197 Megan Mullally 183 Doris Roberts 178 Brad Garrett 175 Peter Boyle 174 Zach Braff 161 Source: E-Poll Market Research E-Score Analysis, 2006, 2007. Eric McCormack 160 Index of Average Female/Male Performer: Awareness, A18-34 Courtney Thorne-Smith 157 Mila Kunis 156 5 Patricia Heaton 153 Measures of Viewer Affinity • Identify with • Trustworthy • Stylish 6 Young Adult Viewers: Identify With Syndication’s Sitcom Stars Ident ify Personality Index Zach Braff 242 Danny Masterson 227 Topher Grace 205 Debra Messing 184 Bernie Mac 174 Matthew Perry 169 Courtney Cox-Arquette 163 Jane Kaczmarek 163 Jim Belushi 161 Peter Boyle 158 Matt LeBlanc 156 Tisha Campbell-Martin 150 Megan Mullally 149 Jennifer Aniston 145 Brad Garrett 140 Ray Romano 137 Laura Prepon 136 Patricia Heaton 131 Source: E-Poll Market Research E-Score Analysis, 2006, 2007. -

July 14–19, 2019 on the Campus of Belmont University at Austin Peay State University

July 14–19, 2019 On the Campus of Belmont University at Austin Peay State University OVER 30 years as Tennessee’s only Center of Excellence for the Creative Arts OVER 100 events per year OVER 85 acclaimed guest artists per year Masterclasses Publications Performances Exhibits Lectures Readings Community Classes Professional Learning for Educators School Field Trip Grants Student Scholarships Learn more about us at: Austin Peay State University does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion, creed, national origin, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity/expression, disability, age, status as a protected veteran, genetic information, or any other legally protected class with respect to all employment, programs and activities sponsored by APSU. The Premier Summer Teacher Training Institute for K–12 Arts Education The Tennessee Arts Academy is a project of the Tennessee Department of Education and is funded under a grant contract with the State of Tennessee. Major corporate, organizational, and individual funding support for the Tennessee Arts Academy is generously provided by: Significant sponsorship, scholarship, and event support is generously provided by the Belmont University Department of Art; Community Foundation of Middle Tennessee; Dorothy Gillespie Foundation; Solie Fott; Bobby Jean Frost; KHS America; Sara Savell; Lee Stites; Tennessee Book Company; The Big Payback; Theatrical Rights Worldwide; and Adolph Thornton Jr., aka Young Dolph. Welcome From the Governor of Tennessee Dear Educators, On behalf of the great State of Tennessee, it is my honor to welcome you to the 2019 Tennessee Arts Academy. We are so fortunate as a state to have a nationally recognized program for professional development in arts education. -

PRIDE PRE&JUDICE About Theatreworks Silicon Valley December 2019 | Volume 51, No

DECEMBER 2019 PRIDE PRE&JUDICE About TheatreWorks Silicon Valley December 2019 | Volume 51, No. 4 Welcome to TheatreWorks Silicon Valley and our 50th season of award-winning theatre! Led by Founding Artistic Director Robert Kelley and Executive Director Phil Santora, TheatreWorks Silicon Valley presents a wide range of productions and programming throughout the region. Tim Bond will become TheatreWorks’ second-ever Artistic Director following Robert Kelley’s retirement in June 2020. Founded in 1970, we continue to celebrate the human spirit and the diversity of our community, presenting contemporary plays and musicals, revitalizing great works of the past, championing arts education, and nurturing new works for the American theatre. TheatreWorks has produced 70 world premieres and over 160 US and regional premieres. In June 2019, TheatreWorks received the highest honor for a theatre not on Broadway— the American Theatre Wing’s 2019 Regional Theatre Tony Award®. TheatreWorks’ 2018/19 season included the world premiere of Hershey Felder: A Paris Love Story, the West Coast premiere of Marie and Rosetta, and regional premieres of Hold These Truths, Native Gardens, Tuck Everlasting, and Archduke. Our 2017 world premiere, The Prince of Egypt, is slated to open on London’s West End in February 2020. With an annual operating budget of $11 million, TheatreWorks produces eight mainstage productions at the Lucie Stern Theatre in Palo Alto and the Mountain View Center for the Performing Arts. Eighteen years ago, we launched the New Works Initiative, -

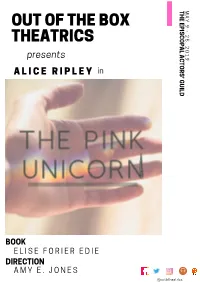

Pink Unicorn Program

M T H A E Y E OUT OF THE BOX 9 P I - S 2 C 5 THEATRICS O , P 2 A 0 L 1 A presents 9 C T O R A L I C E R I P L E Y in S ' G U I L D MUSIC & LYRICS BY STEPHEN SONDHEIM BOOK BY JAMES LAPINE BOOK E L I S E F O R I E R E D I E DIRECTION A M Y E . J O N E S @ootbtheatrics Opening Night: May 15, 2019 The Episcopal Actors' Guild 1 East 29th Street Elizabeth Flemming Ethan Paulini Producing Artistic Director Associate Artistic Director present Alice Ripley* in Out of the Box Theatrics' production of By Elise Forier Edie Technical Design Dialect Coach Costume Design Frank Hartley Rena Cook Hunter Dowell Board Operator Wardrobe Supervisor Joshua Christensen Carrie Greenberg Graphic Design General Management Asst. General Management Gabriella Garcia Maggie Snyder Cara Feuer Press Representative Production Stage Management Ron Lasko Theresa S. Carroll* Directed by AMY E. JONES+ * Actors' Equity OOTB is proud to hire members of + Stage Directors and Association Choreographers Society AUTHOR'S NOTE ELISE FORIER EDIE People often ask me “how much of this play is true?” The answer is, “All of it.” Also, “None of it.” All the events in this play happened to somebody. High school students across the country have been forbidden to start Gay and Straight Alliance clubs. The school picture event mentioned in this play really did happen to a child in Florida. Families across the country are being shunned, harassed and threatened by neighbors, and they suffer for allowing their transgender children to freely express their identities. -

<BEST REVIVAL of a MUSICAL

M N 2018 TONY ➤BEST REVIVAL OF A MUSICAL AWARD WINNER “RAVISHING and GORGEOUS! WHAT A BIG, BOLD DELIGHT IT IS TO ENTER THE WORLD OF ONCE ON THIS ISLAND.” -- The New York Times Tony Award® winner Lea Salonga returns to Broadway in ONCE ON THIS ISLAND, the Broadway musical celebration from the Tony Award®-winning writers of Anastasia and Ragtime. ONCE ON THIS ISLAND is the tale of Ti Moune, a fearless peasant girl who falls in love with a wealthy boy from the other side of the island. When their divided cultures keep them apart, Ti Moune is guided by the powerful island gods, Erzulie (Ms. Salonga), Asaka (Alex Newell, “Glee”), Papa Ge (Merle Dandridge, “Greenleaf”), and Agwe (Quentin Earl Darrington, Cats), on a remarkable quest to reunite with the man who has captured her heart. Bursting with Caribbean colors, rhythms and dance, the story comes to vibrant life in a striking production by Tony Award®-nominated director Michael Arden (Spring Awakening revival) and acclaimed choreographer Camille A. Brown. This production transforms the reality of a tropical village devastated by a storm into a fantastical world alive with hope. Come and gather around for ONCE ON THIS ISLAND, a triumph of the timeless power of theatre to bring us together, move our hearts, and help us conquer life’s storms. You are why we tell the story. CIRCLE IN THE SQUARE THEATRE 235 West 50th Street (between Broadway & 8th Ave.) New York, NY 10019 Groups 10+ GreatWhiteWay.com Opened December 3, 2017 Running Time approx. 90 minutes, with no intermission (212) 757-9117 | (888) 517-0112. -

<I>Spring Awakening</I>

The Journal of American Drama and Theatre (JADT) https://jadtjournal.org Silence, Gesture, and Deaf Identity in Deaf West Theatre's Spring Awakening by Stephanie Lim The Journal of American Drama and Theatre Volume 33, Number 1 (Fall 2020) ISNN 2376-4236 ©2020 by Martin E. Segal Theatre Center For a woman to bear a child, she must . in her own personal way, she must . love her husband. Love him, as she can love only him. Only him . she must love—with her whole . heart. There. Now, you know everything.[1] Frau Bergman, Spring Awakening In the opening scene of Spring Awakening, Wendla begs her mother to explain where babies come from, to which her mother bemoans, “Wendla, child, you cannot imagine—.” In Deaf West Theatre’s version of the show, Frau Bergman speaks this line while bringing her pinky finger up to her head, palm outward, but Wendla quickly corrects the gesture, indicating that her mother has actually inverted the American Sign Language (ASL) for “imagine,” a word signed with palm facing inward.[2] As part of a larger dialogue that closes with the epigraph above, Bergman’s struggle to communicate about sexual intercourse in both ASL and English is one of many exchanges in which adults find themselves unable to communicate effectively with teenagers. The theme of (mis)communication is also evoked through characters’ refusal to communicate with each other at all, as in the musical number “Totally Fucked.” When Melchior’s teachers demand he confess to having authored the obscene 10-page document, “The Art of Sleeping With” (which they claim hastened the suicide of his best friend Moritz), they reject his attempts to explain. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

Thank You, Mr. Falker" Is a Story Close to the Author's Heart

BOOKPALS STORYLINE PRESENTS: "thank"thank you,you, mr.mr. falker"falker" By Patricia Polacco Watch online video of actor Jane Kaczmarek reading this story at http:// www.storylineonline.net Little Trisha is overjoyed at the thought of starting school and learning how to read. But right from the start, when she tries to read, all the letters and numbers just get jumbled up. Her classmates make matters worse by calling her "dummy" and "toad." Then in fifth grade, a new teacher comes. He sees right through the sad little girl to the artist she really is. And when he discovers Trisha's secret -- that she still can't read -- he sets out to help her prove to herself that she can. And will! The autobiographical "Thank you, Mr. Falker" is a story close to the author's heart. It is her personal song of thanks and praise to teachers like Mr. Falker , who quietly but surely change the lives of the children they teach. • Discuss and then write about someone who has made a difference in your life. • Discuss and then write about something that you have ever been teased about. • Discuss and then write about the talent that saved Trisha in the book. • Discuss and then write about a talent that has saved you. • Write a thank you letter to a person that has made a difference in your life. • Compare the art in several books by Patricia Polacco. What are the similarities in the art work? What are the differences in the art work? • Make a display of photographs or illustrations that show your talents. -

Alexandra Mazzucchelli AEA SAG-AFTRA Eligible 718.702.2360 [email protected] Height: 5’7” Hair: Dk

Alexandra Mazzucchelli AEA SAG-AFTRA Eligible 718.702.2360 [email protected] www.alexandramazz.com Height: 5’7” Hair: Dk. Brown Eyes: Amber OFF-BROADWAY My Big Gay Italian Wedding Lucia St. Luke’s Theatre/Dir. Sonia Blangiardo NEW YORK WORKSHOPS La Dottoressa: The Musical Maria Dir. Matty Selman BLISS: A New Musical Princess Janna Dir. Emma Lively,Tyler Beattie Part of the Plan Rita Dir. Lynne-Taylor Corbett THEATRE (PARTIAL) West Side Story Maria Snug Harbor Theatre The Mistress Cycle Ching The Duplex Theatre A New Brain: The Musical Rhoda NYU Tisch RENT Mimi Olmsted Theatre An Old Fashioned Christmas: The Musical Elisabeth MoonMaxx Productions/ Dir. Dennis Grundlock Oliver! Ensemble Harbor Lights Theatre/Dir. Ray Roderick The Wizard of Oz Dorothy The Williamson Theatre Reasons to Be Pretty Carly Adelphi Theatre/Dir. Liz Rothan Sweeney Todd Ensemble NYU Tisch Nine Maddelena NYU Tisch FILM Render To Caesar (Upcoming)* Kaitlin Dir. R. Galluccio A Fine Line Ana Columbia University MFA Film Marked For Mary: The Game Ashley MTV/WWhirlwind Productions, Dir. John Stecenko Planting Love Amber NYU Film Asylum Nurse Davis NYU Film NEW MEDIA Scaley Music Video Principal Spadez Music/Dir. Roan Bibby Restless Child Music Video Principal Charles Fauna Music/Dir. Rachel Kang LIVE PERFORMANCE The NY POPS with Stephanie J. Block Featured Vocalist Carnegie Hall NYC/Music Dir. Steven Reineke & Brian D’Arcy James RMH Annual Gala (Hosted by Barbara Walters) Featured Vocalist Waldorf Astoria/Dir. Michael McElroy B’way Inspirational Voices/ NYU Gala Featured Vocalist Ronald McDonald House/Dir. Michael McElroy NYU New Studio Cabaret Featured Vocalist NYU Tisch/Dir. -

The New Yorker-20180326.Pdf

PRICE $8.99 MAR. 26, 2018 MARCH 26, 2018 6 GOINGS ON ABOUT TOWN 17 THE TALK OF THE TOWN Amy Davidson Sorkin on White House mayhem; Allbirds’ moral fibres; Trump’s Twitter blockees; Sheila Hicks looms large; #MeToo and men. ANNALS OF THEATRE Michael Schulman 22 The Ascension Marianne Elliott and “Angels in America.” SHOUTS & MURMURS Ian Frazier 27 The British Museum of Your Stuff ONWARD AND UPWARD WITH THE ARTS Hua Hsu 28 Hip-Hop’s New Frontier 88rising’s Asian imports. PROFILES Connie Bruck 36 California v. Trump Jerry Brown’s last term as governor. PORTFOLIO Sharif Hamza 48 Gun Country with Dana Goodyear Firearms enthusiasts of the Parkland generation. FICTION Tommy Orange 58 “The State” THE CRITICS A CRITIC AT LARGE Jill Lepore 64 Rachel Carson’s writings on the sea. BOOKS Adam Kirsch 73 Two new histories of the Jews. 77 Briefly Noted THE CURRENT CINEMA Anthony Lane 78 “Tomb Raider,” “Isle of Dogs.” POEMS J. Estanislao Lopez 32 “Meditation on Beauty” Lucie Brock-Broido 44 “Giraffe” COVER Barry Blitt “Exposed” DRAWINGS Roz Chast, Zachary Kanin, Seth Fleishman, William Haefeli, Charlie Hankin, P. C. Vey, Bishakh Som, Peter Kuper, Carolita Johnson, Tom Cheney, Emily Flake, Edward Koren SPOTS Miguel Porlan CONTRIBUTORS The real story, in real time. Connie Bruck (“California v. Trump,” Hua Hsu (“Hip-Hop’s New Frontier,” p. 36) has been a staff writer since 1989. p. 28), a staff writer, is the author of “A She has published three books, among Floating Chinaman.” them “The Predators’ Ball.” Jill Lepore (A Critic at Large, p.