8.202 Stimeling For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Geopolitics, Oil Law Reform, and Commodity Market Expectations

OKLAHOMA LAW REVIEW VOLUME 63 WINTER 2011 NUMBER 2 GEOPOLITICS, OIL LAW REFORM, AND COMMODITY MARKET EXPECTATIONS ROBERT BEJESKY * Table of Contents I. Introduction .................................... ........... 193 II. Geopolitics and Market Equilibrium . .............. 197 III. Historical U.S. Foreign Policy in the Middle East ................ 202 IV. Enter OPEC ..................................... ......... 210 V. Oil Industry Reform Planning for Iraq . ............... 215 VI. Occupation Announcements and Economics . ........... 228 VII. Iraq’s 2007 Oil and Gas Bill . .............. 237 VIII. Oil Price Surges . ............ 249 IX. Strategic Interests in Afghanistan . ................ 265 X. Conclusion ...................................... ......... 273 I. Introduction The 1973 oil supply shock elevated OPEC to world attention and ensconced it in the general consciousness as a confederacy that is potentially * M.A. Political Science (Michigan), M.A. Applied Economics (Michigan), LL.M. International Law (Georgetown). The author has taught international law courses for Cooley Law School and the Department of Political Science at the University of Michigan, American Government and Constitutional Law courses for Alma College, and business law courses at Central Michigan University and the University of Miami. 193 194 OKLAHOMA LAW REVIEW [Vol. 63:193 antithetical to global energy needs. From 1986 until mid-1999, prices generally fluctuated within a $10 to $20 per barrel band, but alarms sounded when market prices started hovering above $30. 1 In July 2001, Senator Arlen Specter addressed the Senate regarding the need to confront OPEC and urged President Bush to file an International Court of Justice case against the organization, on the basis that perceived antitrust violations were a breach of “general principles of law.” 2 Prices dipped initially, but began a precipitous rise in mid-March 2002. -

Re:Imagining Change

WHERE IMAGINATION BUILDS POWER RE:IMAGINING CHANGE How to use story-based strategy to win campaigns, build movements, and change the world by Patrick Reinsborough & Doyle Canning 1ST EDITION Advance Praise for Re:Imagining Change “Re:Imagining Change is a one-of-a-kind essential resource for everyone who is thinking big, challenging the powers-that-be and working hard to make a better world from the ground up. is innovative book provides the tools, analysis, and inspiration to help activists everywhere be more effective, creative and strategic. is handbook is like rocket fuel for your social change imagination.” ~Antonia Juhasz, author of e Tyranny of Oil: e World’s Most Powerful Industry and What We Must Do To Stop It and e Bush Agenda: Invading the World, One Economy at a Time “We are surrounded and shaped by stories every day—sometimes for bet- ter, sometimes for worse. But what Doyle Canning and Patrick Reinsbor- ough point out is a beautiful and powerful truth: that we are all storytellers too. Armed with the right narrative tools, activists can not only open the world’s eyes to injustice, but feed the desire for a better world. Re:Imagining Change is a powerful weapon for a more democratic, creative and hopeful future.” ~Raj Patel, author of Stuffed & Starved and e Value of Nothing: How to Reshape Market Society and Redefine Democracy “Yo Organizers! Stop what you are doing for a couple hours and soak up this book! We know the importance of smart “issue framing.” But Re:Imagining Change will move our organizing further as we connect to the powerful narrative stories and memes of our culture.” ~ Chuck Collins, Institute for Policy Studies, author of e Economic Meltdown Funnies and other books on economic inequality “Politics is as much about who controls meanings as it is about who holds public office and sits in office suites. -

Tyler Priest Curriculum Vitae

Tyler Priest Curriculum Vitae 1817 Oxford St. 325A Melcher Hall Houston, TX 77008 Bauer College of Business (713) 868-4540 University of Houston [email protected] Houston, TX 77204-6201 (713) 743-3669 [email protected] EDUCATION Ph.D. University of Wisconsin-Madison, History (December 1996) Minor Field: Latin American Studies Languages: Portuguese, French M.A. University of Wisconsin-Madison, History (December 1990) B.A. Carleton College, Northfield, Minnesota, History (June 1986) EMPLOYMENT Director of Global Studies and Clinical Professor, C.T. Bauer College of Business, University of Houston, March 2004-present http://www.bauer.uh.edu/search/directory/profile.asp?firstname=Tyler&lastname=Priest http://www.bauerglobalstudies.org/archives/global-studies-faculty-and-staff Senior Policy Analyst, National Commission on the BP Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill and Offshore Drilling, September 2010-April 2011, http://www.oilspillcommission.gov/ Historical Consultant, History of Offshore Oil and Gas Industry in Southern Louisiana Research Project, Minerals Management Service, 2002-2005, MMS OCS Study 2004-049 Visiting Assistant Professor, University of Houston-Clear Lake, August 2000-June 2002 Chief Historian, Shell Oil History Project, 1998-2001 Postdoctoral Fellow, Center for the Americas, University of Houston, 1997-1998 Researcher and Author, Brown & Root Inc. History Project on the Offshore Oil Industry, Houston, Texas, 1996-1997 Visiting Instructor, Middlebury College, 1994-1995 TEACHING FIELDS Energy History Public History Business History Environmental History History of Globalization History of Technology 2 TEACHING EXPERIENCE Courses taught: History of Globalization The United States in WWII History of Globalization (The Case of Petroleum) U.S. History 1914-1945 History of American Frontiers U.S. -

What Are the Effects of US Involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan Since The

C3 TEACHERS World History and Geography II Inquiry (240-270 Minutes) What are the effects of US involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan since the Gulf War? This inquiry was designed by a group of high school students in Fairfax County Public Schools, Virginia. US Marines toppling a statue of Saddam Hussein in Firdos Square, Baghdad, on April 9, 2003 https://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/the-fate-of-a-leg-of-a-statue-of-saddam-hussein Supporting Questions 1. What are the economic effects of US involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan since the Gulf War? 2. What are the political effects of US involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan since the Gulf War? 3. What are the social effects of US involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan since the Gulf War? THIS WORK IS LICENSE D UNDER A CREATIVE C OMMONS ATTRIBUTION - N ONCOMMERCIAL - SHAREAL I K E 4 . 0 INTERNATIONAL LICENS E. 1 C3 TEACHERS Overview - What are the effects of US involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan since the Gulf War? What are the effects of US involvement in Iraq and Afghanistan since the Gulf War? VUS.14 The student will apply social science skills to understand political and social conditions in the United States during the early twenty-first century. Standards and Content WHII.14 The student will apply social science skills to understand the global changes during the early twenty-first century. HOOK: Option A: Students will go through a see-think-wonder thinking routine based off the primary source Introducing the depicting the toppling of a statue of Saddam Hussein, as seen on the previous page. -

Outcome of the World Trade Organization Ministerial in Seattle

OUTCOME OF THE WORLD TRADE ORGANIZATION MINISTERIAL IN SEATTLE HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON TRADE OF THE COMMITTEE ON WAYS AND MEANS HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED SIXTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION FEBRUARY 8, 2000 Serial 106±50 Printed for the use of the Committee on Ways and Means ( U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 66±204 CC WASHINGTON : 2000 VerDate 20-JUL-2000 14:53 Sep 28, 2000 Jkt 060010 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 K:\HEARINGS\66204.TXT WAYS1 PsN: WAYS1 COMMITTEE ON WAYS AND MEANS BILL ARCHER, Texas, Chairman PHILIP M. CRANE, Illinois CHARLES B. RANGEL, New York BILL THOMAS, California FORTNEY PETE STARK, California E. CLAY SHAW, JR., Florida ROBERT T. MATSUI, California NANCY L. JOHNSON, Connecticut WILLIAM J. COYNE, Pennsylvania AMO HOUGHTON, New York SANDER M. LEVIN, Michigan WALLY HERGER, California BENJAMIN L. CARDIN, Maryland JIM MCCRERY, Louisiana JIM MCDERMOTT, Washington DAVE CAMP, Michigan GERALD D. KLECZKA, Wisconsin JIM RAMSTAD, Minnesota JOHN LEWIS, Georgia JIM NUSSLE, Iowa RICHARD E. NEAL, Massachusetts SAM JOHNSON, Texas MICHAEL R. MCNULTY, New York JENNIFER DUNN, Washington WILLIAM J. JEFFERSON, Louisiana MAC COLLINS, Georgia JOHN S. TANNER, Tennessee ROB PORTMAN, Ohio XAVIER BECERRA, California PHILIP S. ENGLISH, Pennsylvania KAREN L. THURMAN, Florida WES WATKINS, Oklahoma LLOYD DOGGETT, Texas J.D. HAYWORTH, Arizona JERRY WELLER, Illinois KENNY HULSHOF, Missouri SCOTT MCINNIS, Colorado RON LEWIS, Kentucky MARK FOLEY, Florida A.L. SINGLETON, Chief of Staff JANICE MAYS, Minority Chief Counsel SUBCOMMITTEE ON TRADE PHILIP M. CRANE, Illinois, Chairman BILL THOMAS, California SANDER M. LEVIN, Michigan E. CLAY SHAW, JR., Florida CHARLES B. -

Breaking up with Bad Banks

BREAKING UP WITH BAD BANKS How Wall Street Makes It Hard to Leave Them – and How We Say Goodbye May 2021 1 Contents Introduction ..................................................................................................................................................... 2 Ideas for Change ............................................................................................................................................. 4 The Move Your Money Movement .............................................................................................................. 5 Obstacles to Moving Your Money ................................................................................................................ 6 Individuals ............................................................................................................................................ 7 Municipalities ....................................................................................................................................... 9 Making the Switch – ..................................................................................................................................... 12 Alternatives to Big Banks ..................................................................................................................... 12 How to Move Your Money ................................................................................................................... 15 Policy Changes to Remove Barriers to Switching Financial Institutions ............................................. -

Environmental Justice and Equity: Case Study New Orleans ENVA M294-J01 SYLLABUS

Environmental Justice and Equity: Case Study New Orleans ENVA M294-J01 SYLLABUS Professors: Phil Bucolo, Ph.D.; [email protected]; Monroe Hall 463 Marianne Cufone, J.D.; [email protected]; Stuart H. Smith Law Clinic and Center for Social Justice (540 Broadway), Rm. 304 Aimée K. Thomas, Ph.D.; [email protected]; Monroe Hall 560 Office Hours: by appointment via Email Class meetings January 4 - 15, 2021: MTWR Student’s Daily Class Preparation 8:00 - 10:00 a.m. MTWR Virtual Synchronous Class via Zoom 10:00 - 11:30 a.m. MTWR In-person experiential learning field trips 1:00 - 4:00 p.m. Course Description: This course provides an overview of the challenges in environmental justice and equity in Greater New Orleans area communities, particularly those identifying as BIPOC and/or low-income, low-access to resources. Students will learn critical thinking and advocacy, integrating doctrine, theory, and skills. This course combines field trips, lectures, discussions, readings, videos, and reflections. Through a review of case studies, media coverage, science, and academic pieces, we will explore issues including systemic socio-economic and racial discrimination, ongoing environmental injustices, inequality in access to basic resources like air, water, land, and food, and other current events and issues. Experiential learning field trips: This course includes a significant experiential component; there will be in-person, hands-on activities (with proper COVID precautions and social distancing). Students will learn and practice skills relative to becoming well-versed in the environmental injustices that are systemic in our culture. First-hand experiences in New Orleans will serve as the case study, but all issues will be transferable across the state, country, and world, thus adhering to the “Think globally, act locally” mantra. -

Maintaining Arctic Cooperation with Russia Planning for Regional Change in the Far North

Maintaining Arctic Cooperation with Russia Planning for Regional Change in the Far North Stephanie Pezard, Abbie Tingstad, Kristin Van Abel, Scott Stephenson C O R P O R A T I O N For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/RR1731 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-0-8330-9745-3 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2017 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Cover: NASA/Operation Ice Bridge. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface Despite a period of generally heightened tensions between Russia and the West, cooperation on Arctic affairs—particularly through the Arctic Council—has remained largely intact, with the exception of direct mil- itary-to-military cooperation in the region. -

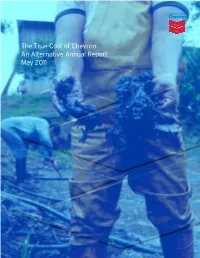

The True Cost of Chevron

The True Cost of Chevron An Alternative Annual Report MAy 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS (Unless otherwise noted, all pieces written by Antonia Juhasz) Introduction . 1. I . Chevron Corporate, Political and Economic Overview Map of Global Operations and Corporate Basics . 2. Political Influence and Connections: How Chevron Spreads its Money Around . 3. Sex, Bribes, and Paintball . .3 General James L . Jones: Chevron’s Oil Man in the White House . 4. William J . Haynes: Chevron’s In-House “Torture Lawyer” . 5. J . Stephen Griles: Current Convict—Ex Chevron Lobbyist . 5. Banking on California . 6. Squeezing Consumers at the Pump . 7. Chevron’s Hype on Alternative Energy . 8. II . The United States Alaska, Trustees for Alaska . 11. Drilling off of America’s Coasts . 13. Colorado, Utah, and Wyoming’s Oil Shale . 15. Richmond, California Refinery . 16. Pascagoula, Mississippi Refinery . 18. Perth Amboy, New Jersey Refinery, CorpWatch . 19. Chevron Sued for Massive Underground Brooklyn Oil Spill . 19. Salt Lake City Utah Refinery Lawsuit . 20. III . Around the World Angola, Mpalabanda . 21. Burma, EarthRights International . 23. Cover photo LEFT: Fire burning at Canada, Rainforest Action Network . 25. the Chevron refinery in Pascagoula, Chad-Cameroon, Antonia Juhasz edits Environmental Defense, Mississippi, photograph by Christy Pritchett ran on August 17, 2007 . Center for Environment & Development, Chadian Association Courtesy of the Press-Register 2007 for the Promotion of Defense of Human Rights . 27. © All rights reserved . Reprinted Ecuador, Amazon Watch . 29. with permission . RIGHT: Ecuadorian workers at former Texaco oil waste pit Iraq, Antonia Juhasz . 32. in Ecuador, photographed by Mitchell Anderson, January 2008 . Kazakhstan, Crude Accountability . 34. -

Cancer Alley and the Fight Against Environmental Racism

Volume 32 Issue 1 Article 2 2-12-2021 Cancer Alley and the Fight Against Environmental Racism Idna G. Castellón Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/elj Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Environmental Law Commons, Fourteenth Amendment Commons, Health Law and Policy Commons, Law and Race Commons, Law and Society Commons, and the State and Local Government Law Commons Recommended Citation Idna G. Castellón, Cancer Alley and the Fight Against Environmental Racism, 32 Vill. Envtl. L.J. 15 (2021). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.villanova.edu/elj/vol32/iss1/2 This Comment is brought to you for free and open access by Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Villanova Environmental Law Journal by an authorized editor of Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law Digital Repository. Castellón: Cancer Alley and the Fight Against Environmental Racism CANCER ALLEY AND THE FIGHT AGAINST ENVIRONMENTAL RACISM I. AN INTRODUCTION TO CANCER ALLEY “Cancer Alley,” also known as “Petrochemical America,” is an area along the Mississippi River spanning from Baton Rouge to New Orleans, Louisiana.1 Cancer Alley houses over 150 petrochemical plants and refineries.2 Petrochemical companies use these plants to refine “crude oil . into a variety of petrochemicals” that are then used to produce everything from construction materials to clothing.3 The most common petrochemical product is plastic.4 The media and local inhabitants -

The True Cost of Chevron an Alternative Annual Report May 2011 the True Cost of Chevron: an Alternative Annual Report May 2011

The True Cost of Chevron An Alternative Annual Report May 2011 The True Cost of Chevron: An Alternative Annual Report May 2011 Introduction . 1 III . Around the World . 23 I . Chevron Corporate, Political and Economic Overview . 2. Angola . 23. Elias Mateus Isaac & Albertina Delgado, Open Society Map of Global Operations and Corporate Basics . .2 Initiative for Southern Africa, Angola The State of Chevron . .3 Australia . 25 Dr . Jill StJohn, The Wilderness Society of Western Australia; Antonia Juhasz, Global Exchange Teri Shore, Turtle Island Restoration Project Chevron Banks on a Profitable Political Agenda . .4 Burma (Myanmar) . .27 Tyson Slocum, Public Citizen Naing Htoo, Paul Donowitz, Matthew Smith & Marra Silencing Local Communities, Disenfranchising Shareholders . .5 Guttenplan, EarthRights International Paul Donowitz, EarthRights International Canada . 29 Resisting Transparency: An Industry Leader . 6. Chevron in Alberta . 29 Isabel Munilla, Publish What You Pay United States; Eriel Tchwkwie Deranger & Brant Olson, Rainforest Paul Donowitz, EarthRights International Action Network Chevron’s Ever-Declining Alternative Energy Commitment . .7 Chevron in the Beaufort Sea . 31 Antonia Juhasz, Global Exchange Andrea Harden-Donahue, Council of Canadians China . .32 II . The United States . 8 Wen Bo, Pacific Environment Colombia . 34 Chevron’s U .S . Coal Operations . 8. Debora Barros Fince, Organizacion Wayuu Munsurat, Antonia Juhasz, Global Exchange with support from Alex Sierra, Global Exchange volunteer Alaska . .9 Ecuador . 36 Bob Shavelson & Tom Evans, Cook Inletkeeper Han Shan, Amazon Watch, with support from California . 11. Ginger Cassady, Rainforest Action Network Antonia Juhasz, Global Exchange Indonesia . 39 Richmond Refinery . 13 Pius Ginting, WALHI-Friends of the Earth Indonesia Nile Malloy & Jessica Tovar, Communities for a Better Iraq . -

The Great Invisible: the BP Deepwater Horizon Disaster and Its Invisible Legacy Entertain Us Environment Movies by John J

Health & Science The Great Invisible: The BP Deepwater Horizon Disaster and its invisible legacy Entertain Us Environment Movies by John J. Berger - May 29, 2015 Margaret Brown's documentary film The Great Invisible asks if the BP Oil Spill is a prologue to future disaster SAN DIEGO, May 29, 2015 – The story of British Petroleum’s Deepwater Horizon is a cautionary tale about the dangers of offshore drilling to people and the environment. It was the nation’s worst oil disaster and its scrutiny illuminates some of the industry’s darker corners. “The Great Invisible,” a new documentary on the BP disaster by filmmaker Margaret Brown, was screened May 12 at the Fairmont Hotel in San Francisco by the Boston-based nonprofit Ceres. Ceres Conference focuses on signs of progress in clean energy The film tells the sad tale of the Deepwater Horizon explosion that killed 11 workers in 2010 and, by one government estimate, disgorged 210 million gallons of oil into the Gulf of Mexico. “The Great Invisible” documents the devastating impact of the spill and its ongoing lethal legacy. BP, of course, has mounted an energetic public relations campaign to show how well it has done by the Gulf since the accident and how clean it now is. But millions of gallons of oil remain in the Gulf, and it has not fully recovered. Perhaps it never will. “The Great Invisible” amply documents the ongoing nightmare that survivors of the BP disaster have endured. It captures the banal suffering and impoverishment left in the spill’s wake as well as BP’s dishonest claim that everyone would be made whole financially after the disaster.