Links Between Landowners and the State,” “The Field of Old English—The Nature of the Language, and Between “Landlordship and Peasant Life” (158)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ellen White's Visions & 2 Esdras

Why Liberalism Failed: Opportunity and Wake-Up Call • “It Was Not Taught Me By Man”: Ellen White’s Visions & 2 Esdras • Sola Scriptura and the Future of Bible Interpretation • A Brief History of the Apocrypha • Erasmus and the New Testament • Ellen White and Blacks, Part III • Unintended Consequences, Accountability, and Being Loved VOLUME 46 ISSUE 1 ■ 2018 SPECTRUM is a journal established to encourage Seventh-day Adventist participation in the discussion of contemporary issues from a Christian viewpoint, to look without prejudice at all sides of a subject, to evaluate the merits of diverse views, and to foster Christian intellectual and cultural growth. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED COPYRIGHT © 2017 ADVENTIST FORUM Although effort is made to ensure accurate scholarship and discriminating judgment, the statements of fact Editor Bonnie Dwyer are the responsibility of contributors, and the views Editorial Assistants Wendy Trim, Linda Terry individual authors express are not necessarily those of Design Mark Dwyer the editorial staff as a whole or as individuals. Spectrum Web Team Alita Byrd, Pam Dietrich, Bonnie Dwyer, Rich Hannon, Steve Hergert, Wendy Trim, Jared SPECTRUM is published by Adventist Forum, a non- Wright, Alisa Williams; managing editor subsidized, nonprofit organization for which gifts are deductible in the report of income for purposes of taxation. The publishing of SPECTRUM depends on subscriptions, gifts from individuals, and the voluntary efforts of the contributors. ABOUT THE COVER Editorial Board: ART AND ARTIST: Beverly Beem Richard Rice SPECTRUM can be accessed on the World Wide Web at Walla Walla, Washington Riverside, California Besides creating art and writing www.spectrummagazine.org. -

Uncovering the Origins of Grendel's Mother by Jennifer Smith 1

Smith 1 Ides, Aglæcwif: That’s No Monster, That’s My Wife! Uncovering the Origins of Grendel’s Mother by Jennifer Smith 14 May 1999 Grendel’s mother has often been relegated to a secondary role in Beowulf, overshadowed by the monstrosity of her murderous son. She is not even given a name of her own. As Keith Taylor points out, “none has received less critical attention than Grendel’s mother, whom scholars of Beowulf tend to regard as an inherently evil creature who like her son is condemned to a life of exile because she bears the mark of Cain” (13). Even J. R. R. Tolkien limits his ground-breaking critical treatment of the poem and its monsters to a discussion of Grendel and the dragon. While Tolkien does touch upon Grendel’s mother, he does so only in connection with her infamous son. Why is this? It seems likely from textual evidence and recent critical findings that this reading stems neither from authorial intention nor from scribal error, but rather from modern interpretations of the text mistakenly filtered through twentieth-century eyes. While outstanding debates over the religious leanings of the Beowulf poet and the dating of the poem are outside the scope of this essay, I do agree with John D. Niles that “if this poem can be attributed to a Christian author composing not earlier than the first half of the tenth century […] then there is little reason to read it as a survival from the heathen age that came to be marred by monkish interpolations” (137). -

Beowulf to Ancient Greece: It Is T^E First Great Work of a Nationai Literature

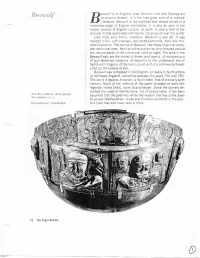

\eowulf is to England what Hcmer's ///ac/ and Odyssey are Beowulf to ancient Greece: it is t^e first great work of a nationai literature. Becwulf is the mythical and literary record of a formative stage of English civilization; it is also an epic of the heroic sources of English cuitu-e. As such, it uses a host of tra- ditional motifs associated with heroic literature all over the world. Liks most early heroic literature. Beowulf is oral art. it was hanaes down, with changes, and embe'lishrnents. from one min- strel to another. The stories of Beowulf, like those of all oral epics, are traditional ones, familiar to tne audiences who crowded around the harp:st-bards in the communal halls at night. The tales in the Beowulf epic are the stories of dream and legend, of monsters and of god-fashioned weapons, of descents to the underworld and of fights with dragons, of the hero's quest and of a community threat- ened by the powers of evil. Beowulf was composed in Old English, probably in Northumbria in northeast England, sometime between the years 700 and 750. The world it depicts, however, is much older, that of the early sixth century. Much of the material of the poem is based on early folk legends—some Celtic, some Scandinavian. Since the scenery de- scribes tne coast of Northumbna. not of Scandinavia, it has been A Celtic caldron. MKer-plateci assumed that the poet who wrote the version that has come down i Nl ccnlun, B.C.). to us was Northumbrian. -

The Inscription of Charms in Anglo-Saxon Manuscripts

Oral Tradition, 14/2 (1999): 401-419 The Inscription of Charms in Anglo-Saxon Manuscripts Lea Olsan Anglo-Saxon charms constitute a definable oral genre that may be distinguished from other kinds of traditionally oral materials such as epic poetry because texts of charms include explicit directions for performance. Scribes often specify that a charm be spoken (cwean) or sung (singan). In some cases a charm is to be written on some object. But inscribing an incantation on an object does not necessarily diminish or contradict the orality of the genre. An incantation written on an amulet manifests the appropriation of the technology of writing for the purposes of a traditionally oral activity.1 Unlike epic poetry, riddles, or lyrics, charms are performed toward specific practical ends and their mode of operation is performative, so that uttering the incantation accomplishes a purpose. The stated purpose of an incantation also determines when and under what circumstances a charm will be performed. Charms inscribed in manuscripts are tagged according to the needs they answer-whether eye pain, insomnia, childbirth, theft of property, or whatever. Some charms ward off troubles (toothache, bees swarming); others, such as those for bleeding or swellings, relieve physical troubles. This specificity of purpose markedly distinguishes the genre from other traditional oral genres that are less specifically utilitarian. Given the specific circumstances of need that call for their performance, the social contexts in which charms are performed create the conditions felicitous for performative speech acts in Austin’s sense (1975:6-7, 12-15). The assumption underlying charms is that the incantations (whether words or symbols or phonetic patterns) of a charm can effect a change in the state of the person or persons or inanimate object (a salve, for example, or a field for crops). -

Current Theology Literature of Christian Antiquity: 1979-1983 Walter J

Theological Studies 45 (1984) CURRENT THEOLOGY LITERATURE OF CHRISTIAN ANTIQUITY: 1979-1983 WALTER J. BURGHARDT, S.J. Georgetown University At the Ninth International Conference on Patristic Studies (Oxford, Sept. 5-10,1983), some 40 reports were scheduled for presentation under the rubric Instrumenta studiorum, i.e., institutions, series of publications, and projects which are of interest to patristic scholars and, more gener ally, students of early Christianity. As on previous occasions, so now, through the graciousness of the Conference's principal organizer, Eliza beth A. Livingstone, and with the co-operation of the scholars who prepared the presentations, it has become possible for me to offer reports on 32 of the instrumenta to a still wider public in these pages. My bulletin is an adaptation, primarily in style, on occasion in content (e.g., fresh information since the Conference); here and there space has exacted a digest. If, therefore, errors have crept in, they must surely be laid to my account (e.g., failure to grasp the exact sense of the original report, especially when composed in a language not native to me). It should be noted that a fair amount of information on the background, purpose, and program of some of the instrumenta is to be found in previous bulletins (cf. TS 17 [1956] 67-92; 21 [1960] 62-91; 33 [1972] 253-84; 37 [1976] 424-55; 41 [1980] 151-80; see also 24 [1963] 437-63). LES PSEUDÉPIGRAPHES D'ANCIEN TESTAMENT1 The year 1963 saw an important project inaugurated on the instruments de travail necessary for study of the OT pseudepigrapha, i.e., nonbiblical and prerabbinic Jewish religious literature. -

Chapter28 He Made Them Welcome

48 BEOWULF 49 armor glistened in the sun. This time he did not greet them roughly, but he rode toward them eagerly. The coast watcher hailed them with cheerful greetings, and Chapter28 he made them welcome. The warriors would be Beowulf went marching with his army of warriors welcome in their home country, he declared . from the sea. Above them the world-candle shone On the beach, the ship was laden with war gear. It bright from the south. They had survived the sea sat heavy with treasure and horses . The mast stood journey, and now they went in quickly to where they high over the hoard of gold-first Hrothgar's, and now knew their protector, king Hygelac, lived with his theirs . Beowulf rewarded the boat's watchman, who warriors and shar ed his treasure. had stayed behind, by giving him a sword bound with Hygelac was told of their arrival, that Beowulf had gold. The weapon would bring the watchman honor. come home . Bench es were quickly readied to receive The ship felt the wind and left the cliffs of the warriors and their leader Beowulf. Hygelac now Denmark. They traveled in deep water, the wind fierce sat, ready to greet them in his court. and straining at the sails, making the deck timbers Then Beowulf sat down with Hygelac, the nephew creak. No hindrance stopped the ship as it boomed with his uncle. Hygelac offered words of welcome, and through the sea, skimmed on the water, winged over Beowulf greeted his king with loyal words. Hygd, waves. -

Violence, Christianity, and the Anglo-Saxon Charms Laurajan G

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1-1-2011 Violence, Christianity, And The Anglo-Saxon Charms Laurajan G. Gallardo Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in English at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Gallardo, Laurajan G., "Violence, Christianity, And The Anglo-Saxon Charms" (2011). Masters Theses. 293. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/293 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. *****US Copyright Notice***** No further reproduction or distribution of this copy is permitted by electronic transmission or any other means. The user should review the copyright notice on the following scanned image(s) contained in the original work from which this electronic copy was made. Section 108: United States Copyright Law The copyright law of the United States [Title 17, United States Code] governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted materials. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the reproduction is not to be used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research. If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excess of "fair use," that use may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. -

Early Mercian Text Production: Authors, Dialects, and Reputations

Early Mercian Text Production: Authors, Dialects, and Reputations Abstract There are suggestions that King Alfred’s legendary literary renaissance may have been a reaction to the efforts of the neighbouring kingdom of Mercia. According to Asser, Alfred assembled a group of literary scholars from this rival Mercian tradition at his court. But it is not clear what early literary activities these scholars could have been involved in to justify their pre-Alfredian reputation. This article tries to outline the historical and literary evidence for early Mercian text production, and the importance of this ‘other’ early literary corpus. What is our current knowledge of Mercian text production and the political and literary relationship of Mercia with Canterbury? What was the relationship of Alfred’s educational movement with its Mercian forerunner? Why is modern scholarship better informed about Alfred’s movement than any Mercian rival culture? If our current knowledge of this area is insufficient for the writing of a literary history of Mercia, a provisional list of texts and bibliography, published electronically for convenient updating, may prove useful in the meantime. Alfredian evidence for Mercian literary culture That King Alfred claims to have initiated an educational Renaissance is well known. Alfredian writings acknowledge a marked decline in learning and scholarship, at least in terms of Latin text composition and manuscript production, and at least in Wessex (Lapidge 1996, 436-439). But the same texts also suggest the existence of -

Proquest Dissertations

Borders and Blood: Creativity in Beowulf by Lisa G. Brown A Dissertation Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English in the Graduate School of Middle Tennessee State University Murfreesboro, Tennessee August 2010 UMI Number: 3430303 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Dissertation Publishing UMI 3430303 Copyright 2010 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 1 7, United States Code. ProQuest® ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Submitted by Lisa Grisham Brown in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, specializing in English. Accepted on behalf of the Faculty of the Graduate School by the dissertation committee: ^rccf<^U—. Date: ?/fc//Ul Ted Sherman, Ph.D. Chairperson Rhonda McDaniel, Ph.D. Second reader ^ifVOA^^vH^^—- Date: 7Ii0IjO Martha Hixon, Ph.D. Third reader %?f?? <éA>%,&¿y%j-fo>&^ Date: G/ (ß //o Tom Strawman, Ph.D. Chair, Department of English ____^ UJo1JIOlQMk/ Date: ^tJlU Michael Allen, Ph.D. Dean of the Graduate School Abstract In Dimensions ofCreativity, Margaret A. Boden defines a bordered, conceptual space as the realm of creativity; therefore, one may argue that the ubiquitous presence of boundaries throughout the Old English poem iteowwZ/suggests that it is a work about creativity. -

“Sitte Ge Sigewif, Sigað to Eorðe”: Settling the Anglo-Saxon Bee Charm Within Its Christian Manuscript Context

https://doi.org/10.7592/Incantatio2018_7_O’Connor “SITTE GE SIGEWIF, SIGAÐ TO EORÐE”: SETTLING THE ANGLO-SAXON BEE CHARM WITHIN ITS CHRISTIAN MANUSCRIPT CONTEXT. Patricia O’Connor The Anglo-Saxon Bee Charm is one of a select number of Old English charms that were previously described as being “strange companions” to the Old English Bede (Grant 5). Written in the outer margin of page 182 of Cambridge, Corpus Christi College MS 41 (CCCC41), the Bee Charm accompanies a passage from Chapter XVII of Book III of the Old English Bede which narrates the consecration of a monastic site. Curiously, however, the Bee Charm’s connection to this passage of the Old English Bede and its influence on our reading of this important text has hitherto been inadequately addressed. Consequently, the objective of this article is to critically reconsider the Bee Charm within its immediate manuscript context and to highlight and evaluate the correspondences shared between the Anglo-Saxon charm and the adjacent passage of the Old English Bede. This codi- cological reassessment seeks to present a new interpretation of the Anglo-Saxon Bee Charm through encouraging a more inclusive reading experience of CCCC41, which incorporates both the margins and the central text. In doing so, this study endeavours to offer significant insights into the function of theBee Charm within Anglo-Saxon society and to contribute to our understanding of how these charms were perceived and circulated within late Anglo-Saxon England. Keywords: Marginalia, Bees, Old English Bede, New Philology, Old English Literature, Palaeography, Scribal Practices. The Anglo-Saxon Bee Charm is one of a number of interesting texts that were inserted anonymously into the margins of a well-known manuscript witness of the Old English Bede. -

Gothic Introduction – Part 1: Linguistic Affiliations and External History Roadmap

RYAN P. SANDELL Gothic Introduction – Part 1: Linguistic Affiliations and External History Roadmap . What is Gothic? . Linguistic History of Gothic . Linguistic Relationships: Genetic and External . External History of the Goths Gothic – Introduction, Part 1 2 What is Gothic? . Gothic is the oldest attested language (mostly 4th c. CE) of the Germanic branch of the Indo-European family. It is the only substantially attested East Germanic language. Corpus consists largely of a translation (Greek-to-Gothic) of the biblical New Testament, attributed to the bishop Wulfila. Primary manuscript, the Codex Argenteus, accessible in published form since 1655. Grammatical Typology: broadly similar to other old Germanic languages (Old High German, Old English, Old Norse). External History: extensive contact with the Roman Empire from the 3rd c. CE (Romania, Ukraine); leading role in 4th / 5th c. wars; Gothic kingdoms in Italy, Iberia in 6th-8th c. Gothic – Introduction, Part 1 3 What Gothic is not... Gothic – Introduction, Part 1 4 Linguistic History of Gothic . Earliest substantively attested Germanic language. • Only well-attested East Germanic language. The language is a “snapshot” from the middle of the 4th c. CE. • Biblical translation was produced in the 4th c. CE. • Some shorter and fragmentary texts date to the 5th and 6th c. CE. Gothic was extinct in Western and Central Europe by the 8th c. CE, at latest. In the Ukraine, communities of Gothic speakers may have existed into the 17th or 18th century. • Vita of St. Cyril (9th c.) mentions Gothic as a liturgical language in the Crimea. • Wordlist of “Crimean Gothic” collected in the 16th c. -

Jordanes and the Invention of Roman-Gothic History Dissertation

Empire of Hope and Tragedy: Jordanes and the Invention of Roman-Gothic History Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Brian Swain Graduate Program in History The Ohio State University 2014 Dissertation Committee: Timothy Gregory, Co-advisor Anthony Kaldellis Kristina Sessa, Co-advisor Copyright by Brian Swain 2014 Abstract This dissertation explores the intersection of political and ethnic conflict during the emperor Justinian’s wars of reconquest through the figure and texts of Jordanes, the earliest barbarian voice to survive antiquity. Jordanes was ethnically Gothic - and yet he also claimed a Roman identity. Writing from Constantinople in 551, he penned two Latin histories on the Gothic and Roman pasts respectively. Crucially, Jordanes wrote while Goths and Romans clashed in the imperial war to reclaim the Italian homeland that had been under Gothic rule since 493. That a Roman Goth wrote about Goths while Rome was at war with Goths is significant and has no analogue in the ancient record. I argue that it was precisely this conflict which prompted Jordanes’ historical inquiry. Jordanes, though, has long been considered a mere copyist, and seldom treated as an historian with ideas of his own. And the few scholars who have treated Jordanes as an original author have dampened the significance of his Gothicness by arguing that barbarian ethnicities were evanescent and subsumed by the gravity of a Roman political identity. They hold that Jordanes was simply a Roman who can tell us only about Roman things, and supported the Roman emperor in his war against the Goths.