Subsistence, Butchery, and Commercialization in Knox County, Tennessee

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Tennessee -& Magazine

Ansearchin ' News, vol. 47, NO. 4 Winter zooo (( / - THE TENNESSEE -& MAGAZINE THE TENNESSEE GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY 9114 Davies Pfmrauon Road on rhe h~srorkDa vies Pfanrarion Mailng Addess: P. O, BOX247, BrunswrCG, 737 38014-0247 Tefephone: (901) 381-1447 & BOARD MEMBERS President JAMES E. BOBO Vice President BOB DUNAGAN Contributions of all types of Temessee-related genealogical Editor DOROTEíY M. ROBERSON materials, including previously unpublished famiiy Bibles, Librarian LORElTA BAILEY diaries, journals, letters, old maps, church minutes or Treasurer FRANK PAESSLER histories, cemetery information, family histories, and other Business h4anager JOHN WOODS documents are welcome. Contributors shouid send Recording Secretary RUTH REED photocopies of printed materials or duplicates of photos Corresponding Secretary BEmHUGHES since they cannot be returned. Manuscripts are subject Director of Sales DOUG GORDON to editing for style and space requirements, and the con- Director of Certiñcates JANE PAESSLER tributofs narne and address wiU & noted in the publish- Director at Large MARY ANN BELL ed article. Please inciude footnotes in the article submitted Director at Large SANDRA AUSTIN and list additional sources. Check magazine for style to be used. Manuscripts or other editorial contributions should be EDITO-. Charles and Jane Paessler, Estelle typed or printed and sent to Editor Dorothy Roberson, 7 150 McDaniel, Caro1 Mittag, Jeandexander West, Ruth Reed, Belsfield Rd., Memphis, TN 38 119-2600. Kay Dawson Michael Ann Bogle, Kay Dawson, Winnie Calloway, Ann Fain, Jean Fitts, Willie Mae Gary, Jean Giiiespie, Barbara Hookings, Joan Hoyt, Thurman Members can obtain information fiom this file by writing Jackson, Ruth O' Donneii, Ruth Reed, Betty Ross, Jean TGS. -

The Future of Knoxville's Past

Th e Future of Knoxville’s Past Historic and Architectural Resources in Knoxville, Tennessee Knoxville Historic Zoning Commission October 2006 Adopted by the Knoxville Historic Zoning Commission on October 19, 2006 and by the Knoxville-Knox County Metropolitan Planning Commission on November 9, 2006 Prepared by the Knoxville-Knox County Metropolitan Planning Commission Knoxville Historic Zoning Commissioners J. Nicholas Arning, Chairman Scott Busby Herbert Donaldson L. Duane Grieve, FAIA William Hoehl J. Finbarr Saunders, Jr. Melynda Moore Whetsel Lila Wilson MPC staff involved in the preparation of this report included: Mark Donaldson, Executive Director Buz Johnson, Deputy Director Sarah Powell, Graphic Designer Jo Ella Washburn, Graphic Designer Charlotte West, Administrative Assistant Th e report was researched and written by Ann Bennett, Senior Planner. Historic photographs used in this document are property of the McClung Historical Collection of the Knox County Public Library System and are used by MPC with much gratitude. TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction . .5 History of Settlement . 5 Archtectural Form and Development . 9 Th e Properties . 15 Residential Historic Districts . .15 Individual Residences . 18 Commercial Historic Districts . .20 Individual Buildings . 21 Schools . 23 Churches . .24 Sites, Structures, and Signs . 24 Property List . 27 Recommenedations . 29 October 2006 Th e Future Of Knoxville’s Past INTRODUCTION that joined it. Development and redevelopment of riverfront In late 1982, funded in part by a grant from the Tennessee sites have erased much of this earlier development, although Historical Commission, MPC conducted a comprehensive there are identifi ed archeological deposits that lend themselves four-year survey of historic sites in Knoxville and Knox to further study located on the University of Tennessee County. -

Leveraging Industrial Heritage in Waterfront Redevelopment

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Theses (Historic Preservation) Graduate Program in Historic Preservation 2010 From Dockyard to Esplanade: Leveraging Industrial Heritage in Waterfront Redevelopment Jayne O. Spector University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses Part of the Historic Preservation and Conservation Commons Spector, Jayne O., "From Dockyard to Esplanade: Leveraging Industrial Heritage in Waterfront Redevelopment" (2010). Theses (Historic Preservation). 150. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/150 Suggested Citation: Spector, Jayne O. (2010). "From Dockyard to Esplanade: Leveraging Industrial Heritage in Waterfront Redevelopment." (Masters Thesis). University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/hp_theses/150 For more information, please contact [email protected]. From Dockyard to Esplanade: Leveraging Industrial Heritage in Waterfront Redevelopment Abstract The outcomes of preserving and incorporating industrial building fabric and related infrastructure, such as railways, docks and cranes, in redeveloped waterfront sites have yet to be fully understood by planners, preservationists, public administrators or developers. Case studies of Pittsburgh, Baltimore, Philadelphia/ Camden, Dublin, Glasgow, examine the industrial history, redevelopment planning and approach to preservation and adaptive reuse in each locale. The effects of contested industrial histories, -

"The Rebellion's Rebellious Little Brother" : the Martial, Diplomatic

“THE REBELLION’S REBELLIOUS LITTLE BROTHER”: THE MARTIAL, DIPLOMATIC, POLITICAL, AND PERSONAL STRUGGLES OF JOHN SEVIER, FIRST GOVERNOR OF TENNESSEE A thesis presented to the faculty of the Graduate School of Western Carolina University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in History. By Meghan Nichole Essington Director: Dr. Honor Sachs Assistant Professor of History History Department Committee Members: Dr. Andrew Denson, History Dr. Alex Macaulay, History April 2014 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are many people who have helped me in making this thesis a reality. It is impossible to name every individual who impacted the successful completion of this study. I must mention Dr. Kurt Piehler, who sparked my interest in Tennessee’s first governor during my last year of undergraduate study at the University of Tennessee. Dr. Piehler encouraged me to research what historians have written about John Sevier. What I found was a man whose history had largely been ignored and forgotten. Without this initial inquiry, it is likely that I would have picked a very different topic to study. I am greatly indebted to Dr. Piehler. While an undergraduate in the history program at UTK I met a number of exceptional historians who inspired and encouraged me to go to graduate school. Dr. Bob Hutton, Dr. Stephen Ash, and Dr. Nancy Schurr taught me to work harder, write better, and never give up on my dream. They have remained mentors to me throughout my graduate career, and their professional support and friendship is precious to me. Also, while at UTK, I met a number of people who have continued to be influential and incredible friends. -

Treadle Powered Machines by Pat Ryan

NUMBER 183 MARCH 2016 A Journal of Tool Collecting published by CRAFTS of New Jersey I think just about Treadle Powered Machines around it. This turns a anyone that collects, uses By Pat Ryan wheel on the machine on or studies tools in any way the table above that powers will stop and take a closer look the machine. Most foot powered at a hand or foot powered ma- machines have a fly wheel. Notice chine when they come across I call them a fly wheel instead of a one. I find them very interesting, pulley. A fly wheel is heavy cast especially when one understands iron that once turning provides the workings involved in getting momentum for the machine to the machine to work properly. power through its cut. Of course Thus I find myself intrigued in many are powered by a different the history of the machine and method. For example, some of the the company that made it during fly wheels are powered by a rod or the early American Industrial bar that is pushed back and forth Revolution. to make it turn. Some have pad- Foot powered machines dles that are pumped up and down are commonly called “treadle such as W. C. Young and Seneca machines”. Treadle machine is Falls. Some companies like W. F. more of a generic term used for a & B. Barns used the velocipede or foot powered machine. Although bicycle peddles method to power many times they are “treadle”, Star treadle scroll saw by Miller Falls the fly wheel. Most hand powered many times they are not. -

21 Life on the Frontier

Life on the Frontier Essential Question: What was life like for people on the Tennessee frontier? Many different factors motivated the settlers who crossed the Appalachian Mountains into the future state of Tennessee. The most important factor was economic opportunity in the forms of trade, farmland and land speculation. While tensions with the Cherokee remained high, the potential profits from trade lured many people to the west. Nathaniel Gist, or Guess, the father of Sequoyah, explored the region with his father in the early 1750s and established strong ties with the Cherokee. Gist eventually set up a trading post on the Long Island of the Holston River. 1 Several of the early traders brought enslaved men to assist in transporting furs across the mountains.2Glowing reports of the fertile land from longhunters and explorers such as Daniel Boone also encouraged people to move west. Finally, men like Richard Henderson and, later, William Blount saw an opportunity to make fortunes through land speculation. Speculators purchased land at low prices with the hope that they could see the land double or triple in value within a few years. Another factor that motivated settlement of the west was the desire to escape high taxes and supposedly corrupt colonial governments. The Regulator movement in western North Carolina challenged the colonial government by intimidating and harassing colonial officials considered to be corrupt. North Carolina Governor Tryon 1 Jeff Biggers, The United States of Appalachia. (Berkeley: Counterpoint,2006), 52. 32-33. 2 Edward McCormack, Slavery on the Tennessee Frontier. (Tennessee American Revolution Bicentennial Commision, 1977), 2. -

4600 Disston Street and 6913 Ditman Street 19135

1. ADDRESS OF HISTORIC RESOURCE (must comply with an Office of Property Assessment address) Street address:__________________________4600 Disston Street and 6913 Ditman______________________ Street __________________ Postal code:_______________19135 2. NAME OF HISTORIC RESOURCE Historic Name:_______________Frank Shuman Home__________________________ and Laboratory _________________________ Current/Common Name:___________________________________________________________ 3. TYPE OF HISTORIC RESOURCE ✔ Building Structure Site Object 4. PROPERTY INFORMATION Condition: excellent good ✔ fair poor ruins Occupancy: ✔ occupied vacant under construction unknown Current use:____________________________________________________________________Multi-family residence (Home) and Contracting company office (Laboratory) 5. BOUNDARY DESCRIPTION Please attach a narrative description and site/plot plan of the resource’s boundaries. 6. DESCRIPTION Please attach a narrative description and photographs of the resource’s physical appearance, site, setting, and surroundings. 7. SIGNIFICANCE Please attach a narrative Statement of Significance citing the Criteria for Designation the resource satisfies. Period of Significance (from year to year): from _________1895 to _________ 1918 Date(s) of construction and/or alteration:_Home________________________ (1895,1995, 1928) and_____________________ Laboratory (circa 1895) Architect, engineer, and/or designer:_________________________________________________ Builder, contractor, and/or artisan:___________________________________________________ -

A Brief History of Knoxville

HOlston Treaty statue on Volunteer landing a brief history of knoxville Before the United States, the Tennessee European discovery of the Mississippi River. country was the mysterious wild place Historians surmise he came right down the beyond the mountains, associated with Native north shore of the Tennessee River, directly American tribes. Prehistoric Indians of the through the future plot of Knoxville. DeSoto Woodland culture settled in the immediate began 250 years of colonial-era claims by Knoxville area as early as 800 A.D. Much Spain, France, and England, none of whom of their story is unknown. They left two effectively controlled the area. British mysterious mounds within what’s now explorers made their way into the region in Knoxville’s city limits. the early 1700s, when the future Tennessee Some centuries later, Cherokee cultures was counted as part of the Atlantic seaboard developed in the region, concentrated some colony of North Carolina. Fort Loudoun, built 40 miles downriver along what became in 1756 about 50 miles southwest of the future known as the Little Tennessee. The Cherokee site of Knoxville, was an ill-fated attempt probably knew the future Knoxville area to establish a British fort during the French mainly as a hunting ground. and Indian War. Hardly three years after Spanish explorer Hernando DeSoto its completion, Cherokee besieged the fort, ventured into the area in 1541 during his capturing or killing most of its inhabitants. famous expedition that culminated in the 1780 JOHN SEVIER LEADS SETTLERS TO VICTORY IN BATTLE OF KING’S MOUNTAIN 1783 1775 revolutionary war 1786 james white builds his fort and mill Hernando DeSoto, seen here on horseback discovering the Mississippi River, explored the East Tennessee region in 1541 3 Treaty of Holston, 1791 pioneers, created a crude settlement here. -

Hans Brunner Tool Auctions April 6, 2013

Hans Brunner Tool Auctions April 6, 2013 PO Box 5238, Brassall Qld 4305 www.hansbrunnertools.gil.com.au 0421 234 645 Vol 24 featuring the collection of Dave Mills, Old Time Builder 1 1 Complete half set of 18 even Hollows & Rounds (2-18) by Marples. Also included are two sash planes numbered 1 &2 plus one of the first named OWT routers I’ve come across. No 12 R is a replacement from a different maker. G+ $ 200-400 2 3 3 Unmarked screw stem plough 2 Rare and early 8 ¾” ebony and plane, boxwood and beech with brass mortice gauge with heavy crisp edges and very good stem brass stock, adjustable from both threads. One of the outer nuts is ends i.e. front adjusts the pins, damaged. G $ 50-100 the back moves the fence. No markings but I’m pretty sure Fenton and Marsden held Reg 970 for this tool. Some minor age cracks, overall G/G + $70-140 4 4 17” beech badger plane with 2 ¼” skewed Ward cutter and dovetailed boxwood wear strip to side. Some bruising to handle and minor damage to boxing. No maker’s mark. G+ $ 60-120 Tool Sales 2013 in April, August & December - to subscribe to free catalogues please write or email. The low estimate is the reserve – I accept any amount on or over the reserve. Send in your bids anytime. Deadline is 12.00 noon on auction day. The highest offer wins. If identical bids are received on a lot the first one in is the winner with one dollar added to clear the bid. -

Philadelphia, Guide to the City

^^^'^y \/?»\^^ %. .^^^>:;^%^^^ .^> iV^ ^•- ^oV* .'. *Ao< V''X^'/V'^^V ''%j^\* 1 ^d^ : ^i 4°-^ *••«»** <b. •no' ^ ^ <^ PHILADELPHIA GUIDE TO THE CITY (Eighth Edition) Compiled by GEORGE eT ^ITZSCHE Recorder of the University of Pennsylvania and First Vice-President of the Philadelphia Rotary Club Issued by THE ROTARY CLUB OF PHILADELPHIA June, 1920 h/6"S -J" Copyright by GEORGE E. NITZSCHE June, 1920 .CU571778 *^ JUL 24 1920 \^ .c PREFACE. This little guide book to Philadelphia was prepared by the editor at the request of the Convention Committee of the Rotary Club. It is not an exhaustive treatise on Philadelphia, but is intended simply as a brief guide for visitors. To make a guide book of a city attractive reading is almost impossible, and to know what to include in a book of limited size is difficult. No two visitors have exactly the same tastes or interests. It is also difficult to classify properly the various points of interest; but it is believed that the classifications herein employed will be found as convenient as any. If some attractions have been given more or less space than they merit, or if anything has been omitted, the editor begs his readers to be indulgent. The real object of this preface is to create an opportunity to thank those who assisted the editor in gathering and com- piling this material. Among them he desires to acknowledge especially the courtesy and assistance of Geo. W. Janvier; the International Printing Co.; Jessie W. Clifton; Charles Fair- child; Elmer Schlichter; Frank H. Taylor; Wm. Rau, for many of the photographs herein reproduced; Jessie C. -

Historic and Architectural Resources in Knoxville and Knox County, Tennessee

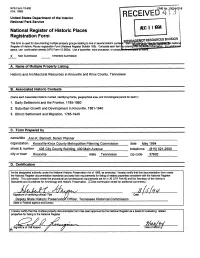

NPS Form 10-900 (Oct. 1990) RECEIVED United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form MERAGENCY RESOURCES DIVISION This form is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contex s See instru^W* ffi/itow«ivQcMnpfaffiffie Nationa Register of Historic Places registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16B). Complete each item space, use continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or comp X New Submission Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Historic and Architectural Resources in Knoxville and Knox County, Tennessee B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each Associated Historic Context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each>) 1. Early Settlement and the Frontier, 1785-1860 2. Suburban Growth and Development in Knoxville, 1861-1940 3. Ethnic Settlement and Migration, 1785-1940 C. Form Prepared by name/title Ann K. Bennett, Senior Planner organization Knoxville-Knox County Metropolitan Planning Commission date May 1994 street & number 403 City County Building, 400 Main Avenue__________ telephone (615)521-2500 city or town Knoxville state Tennessee zip code 37902_____ D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for listing of related properties consistent with the -

The Library Development Review 1994-95

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Other Library Materials (Newsletters, Reports, Library Development Review Etc.) 11-1-1995 The Library Development Review 1994-95 University of Tennessee Libraries Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_libdevel Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons Recommended Citation Lloyd, James and Simic, Laura (eds). The Library Development Review. Knoxville: University of Tennessee, 1994/1995. This Review is brought to you for free and open access by the Other Library Materials (Newsletters, Reports, Etc.) at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Library Development Review by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ii!: &; Q t!I e ~ cs: o o ~ E ac o CO ~ ~ ~ ffi ~ I.LJ en ::::> ~ 2 :n --1 ~ t; ca:I < 2: > j D -=LI.1 ~ e-. ~ <';Olllributeti by Cherry. O'('OlllJcr ,I. ('1.1., Xa~h\'iIl(', 'rellll. The jmtly celehrateu and 'popular "TcnJl{'s~cc" Vy'agoll, liO fllvorably known througbllut tilp ;';olllhcru ::itale~, i~ llllHk 0/ l'arcf111ly select· cd, A.nd thoroughly sca"olled tlmher, .Llld beRt l(ftlUeS or Kent11cky and Tell1l('R~ct' iroll. Its oi!>Un guJi.,hillg-IClIlurl'" arc ib cxceedill~ LfGlIl':-.'E~S OF DRA FT autl DURABILITY. III appcnrance it Is lIellt and attra('tive, Ilnd in style and JiniHh i~ not excelI'd by any wll:,:on ill the IIlHrkct. We caunot ~i\'c it IL hiJl:hcr recommendation tlllm to ~ay we retuin ALII our olu CUl>lOmer~, :md lire constalltly milking new' ncs.