Masaryk University in Brno Faculty of Education

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Razorcake Issue #09

PO Box 42129, Los Angeles, CA 90042 www.razorcake.com #9 know I’m supposed to be jaded. I’ve been hanging around girl found out that the show we’d booked in her town was in a punk rock for so long. I’ve seen so many shows. I’ve bar and she and her friends couldn’t get in, she set up a IIwatched so many bands and fads and zines and people second, all-ages show for us in her town. In fact, everywhere come and go. I’m now at that point in my life where a lot of I went, people were taking matters into their own hands. They kids at all-ages shows really are half my age. By all rights, were setting up independent bookstores and info shops and art it’s time for me to start acting like a grumpy old man, declare galleries and zine libraries and makeshift venues. Every town punk rock dead, and start whining about how bands today are I went to inspired me a little more. just second-rate knock-offs of the bands that I grew up loving. hen, I thought about all these books about punk rock Hell, I should be writing stories about “back in the day” for that have been coming out lately, and about all the jaded Spin by now. But, somehow, the requisite feelings of being TTold guys talking about how things were more vital back jaded are eluding me. In fact, I’m downright optimistic. in the day. But I remember a lot of those days and that “How can this be?” you ask. -

We're Not Nazis, But…

August 2014 American ideals. Universal values. Acknowledgements On human rights, the United States must be a beacon. This report was made possible by the generous Activists fighting for freedom around the globe continue to support of the David Berg Foundation and Arthur & look to us for inspiration and count on us for support. Toni Rembe Rock. Upholding human rights is not only a moral obligation; it’s Human Rights First has for many years worked to a vital national interest. America is strongest when our combat hate crimes, antisemitism and anti-Roma policies and actions match our values. discrimination in Europe. This report is the result of Human Rights First is an independent advocacy and trips by Sonni Efron and Tad Stahnke to Greece and action organization that challenges America to live up to Hungary in April, 2014, and to Greece in May, 2014, its ideals. We believe American leadership is essential in as well as interviews and consultations with a wide the struggle for human rights so we press the U.S. range of human rights activists, government officials, government and private companies to respect human national and international NGOs, multinational rights and the rule of law. When they don’t, we step in to bodies, scholars, attorneys, journalists, and victims. demand reform, accountability, and justice. Around the We salute their courage and dedication, and give world, we work where we can best harness American heartfelt thanks for their counsel and assistance. influence to secure core freedoms. We are also grateful to the following individuals for We know that it is not enough to expose and protest their work on this report: Tamas Bodoky, Maria injustice, so we create the political environment and Demertzian, Hanna Kereszturi, Peter Kreko, Paula policy solutions necessary to ensure consistent respect Garcia-Salazar, Hannah Davies, Erica Lin, Jannat for human rights. -

Alexander B. Stohler Modern American Hategroups: Lndoctrination Through Bigotry, Music, Yiolence & the Internet

Alexander B. Stohler Modern American Hategroups: lndoctrination Through Bigotry, Music, Yiolence & the Internet Alexander B. Stohler FacultyAdviser: Dr, Dennis Klein r'^dw May 13,2020 )ol, Masters of Arts in Holocaust & Genocide Studies Kean University In partialfulfillumt of the rcquirementfar the degee of Moster of A* Abstract: I focused my research on modern, American hate groups. I found some criteria for early- warning signs of antisemitic, bigoted and genocidal activities. I included a summary of neo-Nazi and white supremacy groups in modern American and then moved to a more specific focus on contemporary and prominent groups like Atomwaffen Division, the Proud Boys, the Vinlanders Social Club, the Base, Rise Against Movement, the Hammerskins, and other prominent antisemitic and hate-driven groups. Trends of hate-speech, acts of vandalism and acts of violence within the past fifty years were examined. Also, how law enforcement and the legal system has responded to these activities has been included as well. The different methods these groups use for indoctrination of younger generations has been an important aspect of my research: the consistent use of hate-rock and how hate-groups have co-opted punk and hardcore music to further their ideology. Live-music concerts and festivals surrounding these types of bands and how hate-groups have used music as a means to fund their more violent activities have been crucial components of my research as well. The use of other forms of music and the reactions of non-hate-based artists are also included. The use of the internet, social media and other digital means has also be a primary point of discussion. -

American Foreign Policy, the Recording Industry, and Punk Rock in the Cold War

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Dissertations Department of History Spring 5-10-2017 Music for the International Masses: American Foreign Policy, The Recording Industry, and Punk Rock in the Cold War Mindy Clegg Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_diss Recommended Citation Clegg, Mindy, "Music for the International Masses: American Foreign Policy, The Recording Industry, and Punk Rock in the Cold War." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2017. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_diss/58 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MUSIC FOR THE INTERNATIONAL MASSES: AMERICAN FOREIGN POLICY, THE RECORDING INDUSTRY, AND PUNK ROCK IN THE COLD WAR by MINDY CLEGG Under the Direction of ALEX SAYF CUMMINGS, PhD ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the connections between US foreign policy initiatives, the global expansion of the American recording industry, and the rise of punk in the 1970s and 1980s. The material support of the US government contributed to the globalization of the recording industry and functioned as a facet American-style consumerism. As American culture spread, so did questions about the Cold War and consumerism. As young people began to question the Cold War order they still consumed American mass culture as a way of rebelling against the establishment. But corporations complicit in the Cold War produced this mass culture. Punks embraced cultural rebellion like hippies. -

Themen Und Analysen Gruppierungen Und Aktivitäten Bezirks- Und Regionalberichte Personen Und Locations

Themen und Analysen Gruppierungen und Aktivitäten Bezirks- und Regionalberichte Personen und Locations Neonazis in Berlin & Brandenburg – eine Antifa-Recherche. Januar 2018 FIGHT#6 BACK Inhalt Von Antifas für Antifas 3 Potsdam 55 Interview mit Antifas 4 Cottbus 57 NPD Berlin 6 Frankfurt (Oder) 62 AfD Berlin 10 Barnim 65 Organisierte Neonazigewalt 19 Oberhavel 67 „Autonome Nationalisten Berlin“ 21 „Freie Kräfte“ im Nordwesten Brandenburgs 70 Die rassistische Mobilisierung in Berlin-Buch 22 Havelland 72 Charlottenburg-Wilmersdorf 25 Bruderschaften 74 Neonazistrukturen in Lichtenberg 28 RechtsRock made in Berlin 78 Marzahn-Hellersdorf 31 RechtsRock in Brandenburg 82 Treptow-Köpenick 33 Neonazis im Kampfsport in Berlin und Brandenburg 86 „Mahnwachen für den Frieden“ 36 Neonazis und Tattooläden 90 BÄRGIDA 39 Neonazilocations in Berlin und Brandenburg 93 „Der III. Weg“ 44 Personenregister 98 Die „Identitäre Bewegung Berlin-Brandenburg“ 47 Anschläge auf Geflüchtetenunterkünfte in Brandenburg 102 Rassistische Mobilisierung in Brandenburg 50 Anschläge auf Geflüchtetenunterkünfte in Berlin 104 AfD in Brandenburg 52 Editorial Die Fight Back ist eine Antifa-Recherchepublikation für Berlin und Als Fachblatt für die antifaschistische Praxis richtet sich die Fight Back Brandenburg. Sie portraitiert seit 2001 die Neonaziszene und rechte an alle, die sich mit den Erscheinungsformen der extremen Rechten Aktivitäten – zu Beginn nur in Form einiger Spotlights aus Berlin, gibt aktionistisch, wissenschaftlich, journalistisch und im Bildungsbereich die sechste Ausgabe auf über hundert Seiten einen detailierten Über- auseinandersetzen. Wir wollen diejenigen stärken, die tagtäglich von blick über die Region Berlin-Brandenburg. rechten Zumutungen betroffen sind und dagegen ankämpfen – in ihren Neben Bezirks- und Regionalberichten wird auf einzelne Gruppierun- Kiezen, auf ihren Dörfern, publizistisch wie juristisch, zivilcouragiert gen, Aktions- und Themenschwerpunkte detailierter eingegangen. -

The Public Sphere on the Beach Hartley, John; Green, Joshua

www.ssoar.info The public sphere on the beach Hartley, John; Green, Joshua Postprint / Postprint Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Zur Verfügung gestellt in Kooperation mit / provided in cooperation with: www.peerproject.eu Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Hartley, J., & Green, J. (2006). The public sphere on the beach. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 9(3), 341-362. https://doi.org/10.1177/1367549406066077 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter dem "PEER Licence Agreement zur This document is made available under the "PEER Licence Verfügung" gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zum PEER-Projekt finden Agreement ". For more Information regarding the PEER-project Sie hier: http://www.peerproject.eu Gewährt wird ein nicht see: http://www.peerproject.eu This document is solely intended exklusives, nicht übertragbares, persönliches und beschränktes for your personal, non-commercial use.All of the copies of Recht auf Nutzung dieses Dokuments. Dieses Dokument this documents must retain all copyright information and other ist ausschließlich für den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen information regarding legal protection. You are not allowed to alter Gebrauch bestimmt. Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments this document in any way, to copy it for public or commercial müssen alle Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise purposes, to exhibit the document in public, to perform, distribute auf gesetzlichen Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses or otherwise use the document in public. Dokument nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen By using this particular document, you accept the above-stated Sie dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke conditions of use. vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. Mit der Verwendung dieses Dokuments erkennen Sie die Nutzungsbedingungen an. -

Punk Preludes

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work Summer 8-1996 Punk Preludes Travis Gerarde Buck University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Recommended Citation Buck, Travis Gerarde, "Punk Preludes" (1996). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/160 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Punk Preludes Travis Buck Senior Honors Project University of Tennessee, Knoxville Abstract This paper is an analysis of some of the lyrics of two early punk rock bands, The Sex Pistols and The Dead Kennedys. Focus is made on the background of the lyrics and the sub-text as well as text of the lyrics. There is also some analysis of punk's impact on mondern music During the mid to late 1970's a new genre of music crept into the popular culture on both sides of the Atlantic; this genre became known as punk rock. Divorcing themselves from the mainstream of music and estranging nlany on their way, punk musicians challenged both nlusical and cultural conventions. The music, for the most part, was written by the performers and performed without worrying about what other people thought of it. -

Progressive Poetics

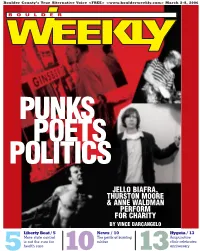

Boulder County’s True Alternative Voice <FREE> <www.boulderweekly.com> March 2-8, 2006 PUNKS POETS POLITICS JELLO BIAFRA, THURSTON MOORE & ANNE WALDMAN PERFORM FOR CHARITY BY VINCE DARCANGELO Liberty Beat / 5 News / 10 Hygeia / 13 More state control The perils of burning Acupuncture is not the cure for rubber clinic celebrates 5 health care 10 13 anniversary inside Page 21 / Overtones: Hip-hop eye exam buzzhttp://www.boulderweekly.com/buzzlead.html Page 26 / High Decibel: Sex convention blues Page 29 / Getting it on!: Sex holiday in Cambodia ProgressiveProgressive Page 35 / Screen: poeticspoetics Delapa handicaps the Oscars cutsbuzz Can’t-miss events for [ the upcoming week ] buzz Flogging Molly Thursday Greyboy Allstars—Sax legend Karl Denson delivers the funk, jazz and good-time boogaloo with the Greyboy Allstars. Fox Theatre, 1135 13th St., Boulder, 303-443-3399. was no holiday in Cambodia for Khyentse James when on Dec. Friday Art and activism 21, 2005, she drove her motorcycle into a 10-foot ditch at 90 Napalm Death—More than two decades mph, shattering her right leg into nine pieces. Though an experi- since defining the grindcore genre, Napalm enced biker, she was traversing a dangerous, barely accessible Death continues to assault America with its come together to Cambodian jungle in search of rarely seen temples. So remote was brash brand of heavy metal. Bluebird It Theatre, 3317 E. Colfax Ave., Denver, 303- the location that it took eight hours for help to arrive and another eight hours to benefit migrant deliver James to the nearest medical facility—a facility that was unable to treat 322-2308. -

The Punk Vault : God Save the Queen a Punk Rock Anthology DVD

The Punk Vault : God Save the Queen A Punk Rock Anthology DVD http://www.punkvinyl.com/2006/01/05/god-save-the-queen-a-punk-rock... The Punk Vault « The LFCM site gets a face lift God Save the Queen A Punk Rock Anthology DVD God Save the Queen: A Punk Rock Anthology - DVD Music Video Distributors God Save the Queen is a collection of mostly live footage of old New York and UK punk rock bands from the early days. Each band featured on this disc has one song and a few feature some early interview footage along with the video. Quite a few of the live performances feature video edited together from various sources to either a live or a studio track, and others such as The Adicts are just a straight up MTV style video. In total there are 20 clips on the disc, 19 of which are videos and one of which is a short interview with Marky Ramone. Some of the footage here was taken from other DVDs that is available through MVD or other sources, and a good portion of it I have never seen before. The disc starts off with the Dead Boys doing “Sonic Reducer” from the Live DVD that was released in 2005. Johnny Thunders follows with a live rendition of “Born to Lose”. The footage for this one was shot at two different live shows from what appeared to be a few years 1 of 13 1/5/2006 3:28 PM The Punk Vault : God Save the Queen A Punk Rock Anthology DVD http://www.punkvinyl.com/2006/01/05/god-save-the-queen-a-punk-rock.. -

Punk Lyrics and Their Cultural and Ideological Background: a Literary Analysis

Punk Lyrics and their Cultural and Ideological Background: A Literary Analysis Diplomarbeit zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Magisters der Philosophie an der Karl-Franzens Universität Graz vorgelegt von Gerfried AMBROSCH am Institut für Anglistik Begutachter: A.o. Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr. Hugo Keiper Graz, 2010 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE 3 INTRODUCTION – What Is Punk? 5 1. ANARCHY IN THE UK 14 2. AMERICAN HARDCORE 26 2.1. STRAIGHT EDGE 44 2.2. THE NINETEEN-NINETIES AND EARLY TWOTHOUSANDS 46 3. THE IDEOLOGY OF PUNK 52 3.1. ANARCHY 53 3.2. THE DIY ETHIC 56 3.3. ANIMAL RIGHTS AND ECOLOGICAL CONCERNS 59 3.4. GENDER AND SEXUALITY 62 3.5. PUNKS AND SKINHEADS 65 4. ANALYSIS OF LYRICS 68 4.1. “PUNK IS DEAD” 70 4.2. “NO GODS, NO MASTERS” 75 4.3. “ARE THESE OUR LIVES?” 77 4.4. “NAME AND ADDRESS WITHHELD”/“SUPERBOWL PATRIOT XXXVI (ENTER THE MENDICANT)” 82 EPILOGUE 89 APPENDIX – Alphabetical Collection of Song Lyrics Mentioned or Cited 90 BIBLIOGRAPHY 117 2 PREFACE Being a punk musician and lyricist myself, I have been following the development of punk rock for a good 15 years now. You might say that punk has played a pivotal role in my life. Needless to say, I have also seen a great deal of media misrepresentation over the years. I completely agree with Craig O’Hara’s perception when he states in his fine introduction to American punk rock, self-explanatorily entitled The Philosophy of Punk: More than Noise, that “Punk has been characterized as a self-destructive, violence oriented fad [...] which had no real significance.” (1999: 43.) He quotes Larry Zbach of Maximum RockNRoll, one of the better known international punk fanzines1, who speaks of “repeated media distortion” which has lead to a situation wherein “more and more people adopt the appearance of Punk [but] have less and less of an idea of its content. -

Reviews Punk Page 1 of 14

God Save The Sex Pistols - Reviews Punk Page 1 of 14 REVIEWS PUNK This section covers non - Pistols products which I have enjoyed and may be of interest to Sex Pistols' fans. Bad Brains - Live at CBGB 1982 (Wienerworld WNRD2393) Released 25th September 2006 In the early 80s, with punk largely on the wane back in the UK, over in the US the Hardcore scene was exploding. Filmed at a three-day Hardcore festival held at CBGB's 24-26th December 1982, the DVD brings together footage from the festival. Bad Brains are perhaps unique in hardcore terms as they intersperse full-on thrash, such as Big Take Over and Riot Squad, with great reggae grooves like King Of Glory. What's most striking about the footage, as well as the intensity of the band, is the audience who are so into the band they go crazy, spilling on and off the stage dancing like punks possessed. It's chaos. If you think you know how to mix it up at a punk show, think again. "Someone get this dude, he's bleedin" says vocalist H.R.as a punter sustains an injury. It's captured on film by multiple cameras both off stage and on, often getting caught up in the action. Bad Brains belong in the top echelons of US Hardcore, along with Black Flag and the Dead Kennedys. Fast, accomplished and wild. Which brings us onto... Dead Kennedys - In God We Trust Inc. The Lost Tapes (Wienerworld WNRD2207) Brilliant. In God We Trust Inc. was a landmark EP heralding the arrival of Hardcore. -

Atom and His Package Possibly the Smallest Band on the List, Atom & His

Atom and His Package Possibly the smallest band on the list, Atom & his Package consists of Adam Goren (Atom) and his package (a Yamaha music sequencer) make funny punk songs utilising many of of the package's hundreds of instruments about the metric system, the lead singer of Judas Priest and what Jewish people do on Christmas. Now moved on to other projects, Atom will remain the person who told the world Anarchy Means That I Litter, The Palestinians Are Not the Same Thing as the Rebel Alliance Jackass, and If You Own The Washington Redskins, You're a ****. Ghost Mice With only two members in this folk/punk band their voices and their music can be heard along with such pride. This band is one of the greatest to come out of the scene because of their abrasive acoustic style. The band consists of a male guitarist (I don't know his name) and Hannah who plays the violin. They are successful and very well should be because it's hard to 99 when you have such little to work with. This band is off Plan It X records and they put on a fantastic show. Not only is the band one of the leaders of the new genre called folk/punk but I'm sure there is going to be very big things to come from them and it will always be from the heart. Defiance, Ohio Defiance, Ohio are perhaps one of the most compassionate and energetic leaders of the "folk/punk" movement. Their clever lyrics accompanied by fast, melodic, acoustic guitars make them very enjoyable to listen to.