Judicial Review in India: Limits and Policy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JOURNALS of the RAJYA SABHA (TWO HUNDRED and TWENTY NINTH SESSION) MONDAY, the 5TH AUGUST, 2013 (The Rajya Sabha Met in the Parliament House at 11-00 A.M.) 11-00 A.M

JOURNALS OF THE RAJYA SABHA (TWO HUNDRED AND TWENTY NINTH SESSION) MONDAY, THE 5TH AUGUST, 2013 (The Rajya Sabha met in the Parliament House at 11-00 a.m.) 11-00 a.m. 1. National Anthem National Anthem was played. 11-02 a.m. 2. Oath or Affirmation Shrimati Kanimozhi (Tamil Nadu) made and subscribed affirmation and took her seat in the House. 11-05 a.m. 3. Obituary References The Chairman made references to the passing away of — 1. Shri Gandhi Azad (ex-Member); 2. Shri Madan Bhatia (ex-Member); 3. Shri Kota Punnaiah (ex-Member); 4. Shri Samar Mukherjee (ex-Member); and 5. Shri Khurshed Alam Khan (ex-Member). The House observed silence, all Members standing, as a mark of respect to the memory of the departed. 1 RAJYA SABHA 11-14 a.m. 4. References by the Chair (i) Reference to the Victims of Flash Floods, Cloudburst and landslides in Uttarakhand and floods due to heavy monsoon rains in several parts of the country The Chairman made a reference to the flash floods, landslides and cloudbursts that took place in Uttarakhand, in June, 2013, in which 580 persons lost their lives, 4473 others were reportedly injured and approximately 5526 persons are reportedly missing. A reference was also made to 20 security personnel belonging to the Indian Air Force National Disaster Response Force and ITBP, involved in rescue and relief operations who lost their lives in a MI-17 Helicopter crash on the 25th of June, 2013 and to the loss of lives and destruction of crops, infrastructure and property in several other parts of the country due to heavy monsoon rains. -

Lok Sabha Debates

Fifth Series, Vol . LXIII No. 6 Tuesday, August 17, 1976 Sravana 26, 1898 (Saka) Lok Sabha Debates (Seventeenth Session) (Vol . LXIII, contains Nos. 1-10) LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT New Delhi Price- Rs 2.00 CONTENTS (Fifth Series, Volume LXI1I, Seventeenth Session, 1976) No. 6, Tuesday, August 77, rgj&fSravaha 26, r8g8(Saka) Columns Ortfl Answers to Questions: ^Starred Questions Nos. 102, 106, 108, n o , 111, 117, and 118 1— 21 TOittefr Answers to Questions : Starred Questions Nos. 101, 103, 105, 107, 109, 112 to 116, 119 and 1 2 0 . ......................................................................21— 28 Unstarred Questions Nos. 842 to 862, 864 to 876, 878 to 883, 885 to 903, 905 to 921,9*3 to 933 and 935 to 953. 28— 1x3 Papers laid on the T a b l e ..................................................................... 113— 21 Committee on Private Members* Bills and Resolutions— 121 Sixty-sixth R e p o r t .................................... Committee on the Welfare of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes— Fifty-fourth, Fifty-fifth and Fifty-sixth Reports • 121— 22 Delhi Sales Tax (Amendment and Validation) Bill— Introduced • 122— 23 Territorial Waters, Continental Shelf, Exclusive Economic Zone and Other Maritime Zones Bill— Motion to consider, as passed by Rajya Sabha— Shri Jagannath Rao 123— 29 Shri Samar Mukherjee 129— 32 Shri K. Narayana Rao . 132—37 Shri Indrajit Gupta 137— 47 Shri B. V. Naik 147—52 Dr. Henry Austin 152— 56 Shri Hari Singh 156— 58 Shri H. R. Gokhale 158-75 •The sign + marked above the name of a Member indicates that the quqUjon was actually asked on the floor of the House by that Member, 00 COLUMNS Clauses a to 16 and i ................................................................... -

List of Pending Applications for Amnesty Scheme Are As Listed

List of Pending Applications for Amnesty Scheme are as listed. Complete these applications by 01/04/2015 04:30 pm. After this period all these pending applications will not be able to avail the amnesty Scheme. LIST OF APPLICATIONS PENDING FOR COMPLETION (USING AMNESTY SCHEME) Application Application Date NAME TRADE NAME MOBILE EMAIL No 20150067718 31/03/2015 21:58:32 NARAYAN DAS N D ENTERPRISE 9932881038 [email protected] 20150067717 31/03/2015 21:58:27 AMIT JHA 9143844467 20150067714 31/03/2015 21:57:50 MANICK SHAW 9331904048 20150067713 31/03/2015 21:57:33 ARCON ELECTRICALS PVTLTD ARCON ELECTRICALS PVT LTD 9433718245 [email protected] STONECRAFT MINERALS STONECRAFT MINERALS PRIVATE 20150067711 31/03/2015 21:56:46 9163878473 [email protected] PRIVATELTD LIMITED 20150067710 31/03/2015 21:56:07 SASWATA GHOSH 9088563010 KARMAKAR APPARELS PRIVATE 20150067707 31/03/2015 21:54:49 JAI KARMAKAR 9143328231 [email protected] LIMITED 20150067703 31/03/2015 21:53:44 ARUN KUMAR CHHAPOLIA GREENLINE VANIJYA PRIVATE 9425325772 [email protected] 20150067692 31/03/2015 21:48:34 RAJ KUMAR MUNDHRA 9831044898 [email protected] 20150067691 31/03/2015 21:48:16 CHANDRA PRAKASH BAGRI M/S.VINAYAK BUSINESS PVT LTD 9831071110 [email protected] MAHAGANAPATI INSTITUTE OF 20150067689 31/03/2015 21:47:38 GOSTHA BEHARI DAS 9830239284 [email protected] MEDICAL SCIENCE AND RESERCH 20150067680 31/03/2015 21:45:11 SANTIFIBRE INDUSTRIES INDIA SANTI FIBRE INDUSTRIES INDIA 9830065928 [email protected] 20150067675 -

Lok Sabha Debates

Fifth Series VoL LYUI-No. 5. Friday, Match t2 ,1976 Pbalguna 22, 1897(Saka) LOK SABHA DEBATES (Sixteenth Session) jpraa nm (Fb/. LV1I I contains Nos. 1 — j o ) LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI Price : Rs. 2.00 CONTENTS No. 5, Friday, March 12, i<yjSjphalguna 22,1897 (&*&*) Oral Answers to Questions: COLOMKS ♦Starred Questions Nos. 81, 82,98 and 83 to 88 , 1—32 Written Answers to Questions : Starred Questions Nos. 89 to 97, 99 and 100 , 32—41 Unstarred Questions Nos. 444 to 489,491 to 549,551,552 and 554 to 566 ..........................................................................41—142 Papers laid on the Table ....................................................... M3 *44 Messages from Rajya Sabha .............................................. 145 Bills as passed by Rajya S a b h a ........................................................ 145 Business of the House . ' ....................................... 146 Joint Committee on Offices of Profit— Recommendation to Rajya Sabha to elect a Member . 146-47 Supplementary Demands for Grants (General), 1975-76 . 147—60 Shrimati Sushila Rohatgi .....................................147—52 Appropriation (No. 3) Bill, 1976—Introduced— Motion to consider— Shrimati Sushila Rohatgi 161 Clauses 2, 3 and 1 161 Motion to pass— Shrimati Sushila Rohatgi . 162 Railway Budget, 1976-77 —General Discussion— Shri Samar Mukherjee . 162—78 Prof. Narain Chand Parashar . 178 86 Shrimati Parvathi Krishnan . 186—98 Shri S. A. Kader 198—206 Shri Bhagwat Jha Azad . 206 14 •The sign + marked above the name of a member indicates that the Question was actually asked on the floor of House by that Member. oo C o l u m n s Constitution (Amendment) Bill . * , , _ 214—270 {Amendment o/JPart III) by Shri Bhogexira Jha * Motion to consider— Shri Bhogendra Jha 214—25 Shri Dasaratha Deb ....................................226—31 Shri B. -

FMRAI-August

Rs.3 Vol. XIII No. 1 KOLKATA FMRAI NEWS 1 AUGUST 2013 Organ of Federation of Medical And Sales Representatives’ Associations of India 60-A Charu Avenue • Kolkata-700 033 • Phone : (033)24242862 • Fax : (033)24244943 • www.fmrai.org • E-mail : [email protected] Fight MNC Penetration Remove Tax on NLEM The working committee meeting of FMRAI, held at Nagpur on 19-20 July, decided to observe countrywide Protest Day On Labour on 23 August against increasing multinational penetration in Indian market; for price control on all medicines and for Related removal of all taxes from the medicines in the National List of Essential Medicines (NLEM). Demands It is now clear that drug MNCs are coming to grab Indian pharma market replacing Indian sector by acquisition or forcing out. The MNCs are imposing conditionalities on of SPEs the Government who is in deseparation for In the tripartite preparatory meeting, FDI to meet current account deficit. called by the Union Labour Ministry on 28 The MNCs penetration with June, despite it was decided that within a Governmental policy support and actions are month's time the Industrial Tripartite also completely destabilizing Indian pharma Committee for the Sales Promotion market preparing ground for establishing Employees will be constituted; the Central monopolized patented medicines of MNCs. government has not constituted the same In the process the medical representatives' so far. FMRAI, in the meantime received job security and their unrestricted right to work the minutes of the said meeting. are also facing serious threats. During the meeting FMRAI submitted The government has prepared NLEM as 9 point demands which include effective per Supreme Court's direction, but let the Working Committee Meeting at Nagpur enforcement of SPE Act and the Rules price fixation decided by the market in under it and amendment of the Section 9 complete departure from earlier DPCO. -

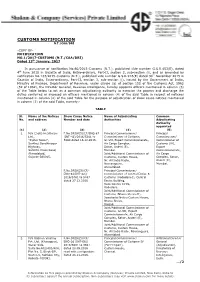

Customs Notification N.T./Caa/Dri

CUSTOMS NOTIFICATION N.T./CAA/DRI -COPY OF- NOTIFICATION NO.1/2017-CUSTOMS (N.T./CAA/DRI) Dated 13th January, 2017 In pursuance of notification No.60/2015-Customs (N.T.), published vide number G.S.R.453(E), dated 4th June 2015 in Gazette of India, Extra-ordinary, Part-II, section 3, sub-section (i), and as amended by notification No.133/2015-Customs (N.T.), published vide number G.S.R.916(E) dated 30th November 2015 in Gazette of India, Extra-ordinary, Part-II, section 3, sub-section (i), issued by the Government of India, Ministry of Finance, Department of Revenue, under clause (a) of section 152 of the Customs Act, 1962 (52 of 1962), the Director General, Revenue Intelligence, hereby appoints officers mentioned in column (5) of the Table below to act as a common adjudicating authority to exercise the powers and discharge the duties conferred or imposed on officers mentioned in column (4) of the said Table in respect of noticees mentioned in column (2) of the said Table for the purpose of adjudication of show cause notices mentioned in column (3) of the said Table, namely:- TABLE Sl. Name of the Noticee Show Cause Notice Name of Adjudicating Common No. and address Number and date Authorities Adjudicating Authority appointed (1) (2) (3) (4) (5) 1. M/s Cadila Healthcare F.No.DRI/KZU/CF/ENQ-87 Principal Commissioner/ Principal Ltd., (INT-42)/2016/5281 to Commissioner of Customs, Commissioner/ “Zydus Tower”, 5284 dated 16.12.2016. Gr-VII, Export Commissionerate, Commissioner of Sarkhej Gandhinagar Air Cargo Complex, Customs (IV), Highway, Sahar, Anderi (E), Export Satellite Cross Road, Mumbai. -

Calcutta & West Bengal, 1950S

People, Politics and Protests I Calcutta & West Bengal, 1950s – 1960s Sucharita Sengupta & Paula Banerjee Anwesha Sengupta 2016 1. Refugee Movement: Another Aspect of Popular Movements in West Bengal in the 1950s and 1960s Sucharita Sengupta & Paula Banerjee 1 2. Tram Movement and Teachers’ Movement in Calcutta: 1953-1954 Anwesha Sengupta 25 Refugee Movement: Another Aspect of Popular Movements in West Bengal in the 1950s and 1960s ∗ Sucharita Sengupta & Paula Banerjee Introduction By now it is common knowledge how Indian independence was born out of partition that displaced 15 million people. In West Bengal alone 30 lakh refugees entered until 1960. In the 1970s the number of people entering from the east was closer to a few million. Lived experiences of partition refugees came to us in bits and pieces. In the last sixteen years however there is a burgeoning literature on the partition refugees in West Bengal. The literature on refugees followed a familiar terrain and set some patterns that might be interesting to explore. We will endeavour to explain through broad sketches how the narratives evolved. To begin with we were given the literature of victimhood in which the refugees were portrayed only as victims. It cannot be denied that in large parts these refugees were victims but by fixing their identities as victims these authors lost much of the richness of refugee experience because even as victims the refugee identity was never fixed as these refugees, even in the worst of times, constantly tried to negotiate with powers that be and strengthen their own agency. But by fixing their identities as victims and not problematising that victimhood the refugees were for a long time displaced from the centre stage of their own experiences and made “marginal” to their narratives. -

Public Relations Directory of Govt. of West Bengal

PUBLIC RELATIONS DIRECTORY OF GOVERNMENT OF WEST BENGAL WEST BENGAL INFORMATION AND CULTURAL CENTRE DEPARTMENT OF INFORMATION AND CULTURAL AFFAIRS GOVERNMENT OF WEST BENGAL 18 and 19, Bhai Vir Singh Marg, New Delhi-110001 Website: http://wbicc.in Office of the Principal Resident Commissioner and Manjusha PUBLIC RELATIONS DIRECTORY Prepared and Compiled by West Bengal Information and Cultural Centre New Delhi Foreword We are delighted to bring out a Public Relations Directory from the West Bengal Information & Cultural Centre Delhi collating information, considered relevant, at one place. Against the backdrop of the new website of the Information Centre (http://wbicc.in) launched on 5th May, 2011 and a daily compilation of news relating to West Bengal on the Webpage Media Reflections (www.wbmediareflections.in) on 12th September, 2011, this is another pioneering effort of the Centre in releasing more information under the public domain. A soft copy of the directory with periodic updates will also be available on the site http://wbicc.in. We seek your comments and suggestions to keep the information profile upto date and user-friendly. Please stay connected (Bhaskar Khulbe) Pr. Resident Commissioner THE STATE AT A GLANCE: ● Number of districts: 18 (excluding Kolkata) ● Area: 88,752 sq. km. ● No. of Blocks : 341 ● No. of Towns : 909 ● No. of Villages : 40,203 ● Total population: 91,347,736 (as in 2011 Census) ● Males: 46,927,389 ● Females: 44,420,347 ● Decadal population growth 2001-2011: 13.93 per cent ● Population density: 1029 persons per sq. km ● Sex ratio: 947 ● Literacy Rate: 77.08 per cent Males: 82.67 per cent Females: 71.16 per cent Information Directory of West Bengal Goverment 2. -

Annexure-I Selected Awardees Under the Scheme of P.G

1 of 101 Pages 6th February, 2014 Annexure-I Selected awardees under the scheme of P.G. Scholarship for Single Girl Child for the academic programme 2013-2015 S.No Candidate ID Name Father Name Mother Name DOB PG Degree Subject Coll/Uni Name final Remarks OSMANIA UNIVERSITY 1 SGC-OBC-2013-13833 KONDA LAXMI KONDA SAILU KONDA SAYAVVA 05/07/1992 M.A POLITICAL SCIENCE Awarded 2 SGC-SC-2013-15220 ANUSREE SAHA MANIKESWAR SAHA BAISALI SAHA 10/10/1991 M.SC ZOOLOGY THE UNIVERSITY OF BURDWAN Awarded 3 SGC-GEN-2013-17416 LAKSHMI S KUMAR S SUDHEER KUMAR K R SUDHA KUMARY 05/02/1993 MA MALAYALAM FATHIMA MATHA NATIONAL COLLEGE Awarded HAM-AK RURAL COLLEGE OF MANAGEMENT & 4 SGC-GEN-2013-17858 MISSPAB JALIL ULLAH SAMSUN NAHER 30/08/1987 M.A EDUCATION TECHNOLOGY Awarded 5 SGC-GEN-2013-18801 SCINDIA A RAMASAMY R EMALDA 05/03/1991 M.SC physics SHRIMATHI INDHRA GANDHI COLLEGE TRICHY Awarded 6 SGC-GEN-2013-13773 SYAMA S PILLAI MURALEEDHARAN PILLAI B SAKUNTHALAMURALI 14/04/1993 MSC PHYSICS CATHOLICATE COLLEGE-PATHANAMTHITTA Awarded 7 SGC-GEN-2013-12968 A ARAVINTHALAKSHMI N ANNAMALAI A MEENAL ANNAMALAI 13/09/1992 M.A DEVELOPMENT MANAGEMENT MADRAS SCHOOL OF SOCIAL WORK Awarded 8 SGC-OBC-2013-14722 A J ROSHI ROHINI A AZHAKESA PERUMAL PILLAI A JEYALEKSHMI 06/01/1991 MA ENGLISH LITERATURE HOLY CROSS COLLEGE Awarded DHANALAKSHMI SRINIVASAN COLLEGE OF ARTS & 9 SGC-GEN-2013-17494 A JENIFER BABY ANTONY MARIYANATHAN JOSHPINE SAGAYARANI 05/01/1992 M.A ENGLISH SCIENCE FOR WOMEN Awarded 10 SGC-SC-2013-19257 A KALAI SELVI R ANANDHAN A JOTHI MANI 03/12/1992 M.COM commerce and computer applications Bharathiar university Awarded 11 SGC-GEN-2013-12849 A. -

Lok Sabha Debates 1 2

)LIWK6HULHV9RO91R 7KXUVGD\-XO\ $VDGKD 6DND /2.6$%+$'(%$7(6 6HFRQG6HVVLRQ )LIWK/RN6DEKD /2.6$%+$6(&5(7$5,$7 1(:'(/+, 3ULFH5H CONTENTS No. 34—Thursday, July 8, M ljAsadha 17,1893 (Sake) C olumns Oral Answers to Questions: ♦Starred Questions Nos. 991 to 994, 996, 997, 999 and 1002 to 1004. 1—29 Written Answers to Questions : Star ed Questions Nos. 995, 998, 1000, 1001 and 1005 to 1020. 29-44 Unstarred Questions Nos. 4226 to 4228, 4230 to 4259, 4261 to 4276 and 4278 to 4351. 44-145 Calling Attention to Matter of Urgent Public Importance- Reported malpractices and irregularities by Shipping Companies in import of newsprint 145-53 Re. Law and Order Situation in West Bengal ... 153 Re. Supply of Defective Bread in Delhi. ... 153—55 Papers laid on the Table ... 155 Demands for Grants, 1971-72— Ministry of Information and Broadcasting ... 156-76 Shrimati Nandini Satpathy ... 157—72 Ministry of Defence ... 176-276 Shri Samar Mukherjee ... 178—84 Shri Nimbalkar ... 184-88 Shri Indrajit Gupta ... 193—205 Shri B. V. Naik ... 205-08 Shri G. Viswanathan ... 208— 16 Shri Inder J. Malhotra ... 216-19 Shri Brij Raj Singh-Kotah ... ... 219-26 Shri Raja Ram Shastri ... 226-32 Shri D. D. Desai ... ... 232-36 Shri Priya Raojan Das Munsi 236-40 Shri S. A. Shamim in in 240-43 ♦The sign + marked above the name of a Member indicates that the question was actually asked on the floor of the House by that Member. ( « ) C olumns Shri Chandulal Chandrakar ... ... 244—48 Shri Birendar Singh Rao ... ... ... 248—53 Prof. -

Statistical Report General Elections

STATISTICAL REPORT ON GENERAL ELECTIONS, 1971 TO THE FIFTH LOK SABHA VOLUME I (NATIONAL AND STATE ABSTRACTS & DETAILED RESULTS) ELECTION COMMISSION OF INDIA NEW DELHI ECI-GE71-LS (VOL. I) © Election Commision of India,1973 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by mimeograph or any other means, without prior and express permission in writing from Election Commision of India. First published 1973 Published by Election Commision of India, Nirvachan Sadan, Ashoka Road, New Delhi - 110 001. Computer Data Processing and Laser Printing of Reports by Statistics and Information System Division, Election Commision of India. Election Commission of India – General Elections, 1971 (5th LOK SABHA) STATISTICAL REPORT – VOLUME I (National and State Abstracts & Detailed Results) CONTENTS SUBJECT Page No. Part – I 1. List of Participating Political Parties 1 - 2 2. Number and Types of Constituencies 3 3. Size of Electorate 4 4. Voter Turnout and Polling Stations 5 5. Number of Candidates per Constituency 6 - 7 6. Number of Candidates and Forfeiture of Deposits 8 7. State / UT Summary on Nominations, Rejections, 9 - 35 Withdrawals and Forfeitures 8. State / UT Summary on Electors, Voters, Votes Polled and 36 - 62 Polling Stations 9. List of Successful Candidates 63 - 75 10. Performance of National Parties vis-a-vis Others 76 11. Seats won by Parties in States / U.T.s 77 - 80 12. Seats won in States / U.T.s by Parties 81 - 84 13. Votes Polled by Parties - National Summary 85 - 87 14. Votes Polled by Parties in States / U.T.s 88 - 97 15. -

Statistical Handbook of Ministry of Parliamentary Affairs – India

LEGISLATIVE MATTERS (UPDATED UPTO 31ST MARCH, 2009) Table No. Subject 1. Dates of poll, constitution, first sitting expiration of the term and dissolution of the Lok Sabha since 1952 (First to Fourteenth Lok Sabha) 2. Statement showing the dates of constitution, dissolution etc. of various Lok Sabhas since 1952 3. Dates of issue of summons, commencement, adjournment sine-die, prorogation, sittings and duration of various Sessions of Lok Sabha held since 1952 (‘B’ in column 1 stands for Budget Session) 4. Dates of issue of summons, commencement, adjournment sine-die,prorogation, sittings and duration of various Sessions of Rajya Sabha held since 1952 5. Statement showing the interval of less than 15 days between the issue of summons to Members of Lok Sabha and dates of Commencement of sessions since 1962 6. Statement showing the interval of less than 15 days between the issue of summons to Members of Rajya Sabha and dates of Commencement of sessions since 1962 7. Statement showing the names and dates of appointment etc. of the Speakers pro tem 8. Statement showing the dates of election, names of Speaker and Deputy Speaker of the Lok Sabha 9. Dates of election of the Speaker, Lok Sabha and the constitution of the Departmentally related Standing Committees since 1993 10. Statement showing the dates of election and names of the Deputy Chairman of the Rajya Sabha 11. Duration of recess during Budget Sessions since 1993 12. Statement showing the details regarding Sessions of the Lok Sabha etc.when the House remained unprorogued for more than 15 days 13.