William Alberque “The NPT and the Origins of NATO's Nuclear Sharing Arrangements”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DIRECTING the Disorder the CFR Is the Deep State Powerhouse Undoing and Remaking Our World

DEEP STATE DIRECTING THE Disorder The CFR is the Deep State powerhouse undoing and remaking our world. 2 by William F. Jasper The nationalist vs. globalist conflict is not merely an he whole world has gone insane ideological struggle between shadowy, unidentifiable and the lunatics are in charge of T the asylum. At least it looks that forces; it is a struggle with organized globalists who have way to any rational person surveying the very real, identifiable, powerful organizations and networks escalating revolutions that have engulfed the planet in the year 2020. The revolu- operating incessantly to undermine and subvert our tions to which we refer are the COVID- constitutional Republic and our Christian-style civilization. 19 revolution and the Black Lives Matter revolution, which, combined, are wreak- ing unprecedented havoc and destruction — political, social, economic, moral, and spiritual — worldwide. As we will show, these two seemingly unrelated upheavals are very closely tied together, and are but the latest and most profound manifesta- tions of a global revolutionary transfor- mation that has been under way for many years. Both of these revolutions are being stoked and orchestrated by elitist forces that intend to unmake the United States of America and extinguish liberty as we know it everywhere. In his famous “Lectures on the French Revolution,” delivered at Cambridge University between 1895 and 1899, the distinguished British historian and states- man John Emerich Dalberg, more com- monly known as Lord Acton, noted: “The appalling thing in the French Revolution is not the tumult, but the design. Through all the fire and smoke we perceive the evidence of calculating organization. -

NATO and the Frameworks of Nuclear Non-Proliferation and Disarmament

NATO and the Frameworks of Nuclear Non-proliferation and Disarmament: Challenges for the for 10th and Disarmament: Challenges Conference NPT Review Non-proliferation of Nuclear and the Frameworks NATO Research Paper Tim Caughley, with Yasmin Afina International Security Programme | May 2020 NATO and the Frameworks of Nuclear Non-proliferation and Disarmament Challenges for the 10th NPT Review Conference Tim Caughley, with Yasmin Afina with Yasmin Caughley, Tim Chatham House Contents Summary 2 1 Introduction 3 2 Background 5 3 NATO and the NPT 8 4 NATO: the NPT and the TPNW 15 5 NATO and the TPNW: Legal Issues 20 6 Conclusions 24 About the Authors 28 Acknowledgments 29 1 | Chatham House NATO and the Frameworks of Nuclear Non-proliferation and Disarmament Summary • The 10th five-yearly Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (the NPT) was due to take place in April–May 2020, but has been postponed because of the COVID-19 pandemic. • In force since 1970 and with 191 states parties, the NPT is hailed as the cornerstone of a rules-based international arms control and non-proliferation regime, and an essential basis for the pursuit of nuclear disarmament. But successive review conferences have been riven by disagreement between the five nuclear weapon states and many non-nuclear weapon states over the appropriate way to implement the treaty’s nuclear disarmament pillar. • Although the number of nuclear weapons committed to NATO defence has been reduced by over 90 per cent since the depths of the Cold War, NATO nuclear weapon states, and their allies that depend on the doctrine of extended nuclear deterrence for their own defence, favour continued retention of the remaining nuclear weapons until the international security situation is conducive to further progress on nuclear disarmament. -

DIRECTING the Disorder the CFR Is the Deep State Powerhouse Undoing and Remaking Our World

Charting the CFR’s Political Dominance • Rethinking Discrimination August 10, 2020 • $3.95 www.TheNewAmerican.com THAT FREEDOM SHALL NOT PERISH DIRECTING THE Disorder The CFR is the Deep State powerhouse undoing and remaking our world. NEW CHINA: THE DEEP STATE’S TROJAN HORSE IN AMERICA This exposé shows that the Chinese Communist plan to subvert America is well underway, and is being aided by the Deep State. Will Americans wake up before the tipping point? By Arthur R. Thompson, CEO, The John Birch Society (2020ed, pb, 132pp, 1-11/$7.95ea; 12-23/$5.95ea; 24-49/$3.95ea; 50+/$2.95ea) BKCDSTHA ✁ Order Online: Mail completed form to: QUANTITY TITLE PRICE TOTAL PRICE ShopJBS • P.O. BOX 8040 www.ShopJBS.org APPLETON, WI 54912 Credit-card orders call toll-free now! 1-800-342-6491 Name ______________________________________________________________ Address ____________________________________________________________ SHIPPING/HANDLING WI RESIDENTS ADD City _____________________________ State __________ Zip ________________ SUBTOTAL (SEE CHART BELOW) 5.5% SALES TAX TOTAL Phone ____________________________ E-mail ______________________________ 0000 ❑ ❑ ❑ 000 0000 000 000 For shipments outside the U.S., please call for rates. Check VISA Discover 0000 0000 0000 00 Order Subtotal Standard Shipping Rush Shipping ❑ Money Order ❑ MasterCard ❑ American Express VISA/MC/Discover American Express Three Digit V-Code Four Digit V-Code $0-10.99 $6.36 $9.95 Standard: 4-14 $11.00-19.99 $7.75 $12.75 business days. Make checks payable to: ShopJBS ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ ___ $20.00-49.99 $9.95 $14.95 Rush: 3-7 business $50.00-99.99 $13.75 $18.75 days, no P.O. -

Turkey, NATO & and Nuclear Sharing

Arms Control Association (ACA) British American Security Information Council (BASIC) Institute for Peace Research and Security Policy at the University of Hamburg (IFSH) Nuclear Policy Paper No. 5 April 2011 1 Mustafa Kibaroglu Turkey, NATO & and Nuclear Sharing: Prospects after NATO's Lisbon Summit In the run-up to the Lisbon summit meeting of NATO on November 19-20, 2010, where the new Strategic Concept of the alliance was adopted, the status of U.S. tactical nuclear weapons deployed in five European countries, namely Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Turkey was a significant topic of debate, and remains so afterwards. Some have suggested the speedy withdrawal of these weapons while others have endorsed their extended stay on the continent for as long as there are nuclear threats to the alliance.2 Turkey, as a host, has long been supportive changes in the deployment of theater of retaining U.S. nuclear weapons on its nuclear weapons in other NATO states is territory for various reasons and also more doubtful. expected others to continue to deploy these weapons as part of the burden sharing and This being the case for the allied countries solidarity principles of the alliance. Turkey in general, and from Turkey’s perspective in believes that the presence of U.S. nuclear particular, this paper will present primarily weapons in Europe strengthens the U.S. the views in the political, diplomatic, and commitment to transatlantic security, and military circles in Turkey with respect to the contributes to the credibility of the extended prolonged deployment of the U.S. -

NATO and Nuclear Disarmament

North Atlantic Treaty Organization www.nato.int/factsheets Factsheet October 2020 NATO and Nuclear Disarmament NATO Allies are strongly committed to arms control, disarmament, and non-proliferation, which play an important role in preserving peace in the Euro-Atlantic region. NATO actively contributes to effective and verifiable nuclear disarmament efforts through its policies and activities, and the commitments of its member countries. Allies recognise the threat posed by weapons of mass destruction (WMD), as well as their means of delivery, by state and non-state actors. NATO designs its partnership programmes to provide effective frameworks for dialogue, consultation, and coordination on a wide range of arms control-related issues, including nuclear disarmament. NATO’s Role in Nuclear Disarmament Disarmament is the act of eliminating or abolishing weapons, either unilaterally or reciprocally. It may refer either to reducing and limiting the number and types of arms, or to eliminating entire categories of weapons. NATO’s policies in this field support consultation and practical cooperation on nuclear policy issues, including arms control, disarmament, and non-proliferation. NATO supports and facilitates policy-making among members, and consultations with partners and other countries, and aids in the implementation of international obligations. All NATO Allies are parties to the most important of the global treaties on WMD, such as the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), the Chemical Weapons Convention, and the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention. NATO consults and cooperates with relevant international organizations, including the UN Office for Disarmament Affairs, the African Union, the League of Arab States, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, and the European Union. -

NATO Nuclear Deterrence

North Atlantic Treaty Organization www.nato.int/factsheets Factsheet February 2020 NATO Nuclear Deterrence Nuclear deterrence has been at the core of NATO’s collective defence for 70 years. In an uncertain world, nuclear weapons continue to play a critical role in NATO’s deterrence and defence. The purpose of NATO’s nuclear capability is to preserve peace, prevent coercion, and deter aggression. Nuclear weapons are unique, and the circumstances in which NATO might contemplate the use of them are extremely remote. However, if the fundamental security of any Ally were to be threatened, NATO has the capabilities and resolve to defend itself – including with nuclear weapons. NATO is committed to creating the conditions for a world without nuclear weapons, in line with Allies’ commitments to the Non-Proliferation Treaty. Since the end of the Cold War, the number of nuclear weapons available to NATO in UK MOD - Crown Copyright Europe has been reduced dramatically, by around 90 percent. However, as long as nuclear weapons exist, NATO will remain a nuclear Alliance and Allies will continue to take all steps necessary to ensure NATO’s nuclear deterrent remains safe, secure and effective. Nuclear Forces Three NATO members - the United States, France and the United Kingdom – have nuclear weapons. The strategic forces of the Alliance, particularly those of the United States, are the supreme guarantee of the Alliance’s security. The independent strategic nuclear forces of the United Kingdom and France have a deterrent role of their own and contribute significantly to the overall security of the Alliance. NATO’s nuclear deterrence also relies on US nuclear weapons deployed in Europe and supporting capabilities and infrastructure provided by Allies. -

Building a Safe, Secure, and Credible NATO Nuclear Posture

Building a Safe, Secure, and Credible NATO Nuclear Posture NUCLEAR THREAT INITIATIVE 1776 Eye St, NW | Suite 600 | Washington DC 20006 www.nti.org Steve Andreasen, Isabelle Williams, Brian Rose, @NTI_WMD Hans M. Kristensen, and Simon Lunn www.facebook.com/nti.org Foreword by Ernest J. Moniz and Sam Nunn ABOUT THE NUCLEAR THREAT INITIATIVE The Nuclear Threat Initiative works to protect our lives, environment, and quality of life now and for future generations. We work to prevent catastrophic attacks with weapons of mass destruction and disruption (WMDD)—nuclear, biological, radiological, chemical, and cyber. Founded in 2001 by former U.S. Senator Sam Nunn and philanthropist Ted Turner, who continue to serve as co-chairs, NTI is guided by a prestigious, international board of directors. Ernest J. Moniz serves as chief executive officer and co-chair; Des Browne is vice chair; and Joan Rohlfing serves as president. www.nti.org Cover: A Dutch F-16 takes off from Leeuwarden Airbase in the Netherlands in 2011. PHOTO BY ROBIN UTRECHT/AFP/GETTY IMAGES Building a Safe, Secure, and Credible NATO Nuclear Posture Steve Andreasen Isabelle Williams Brian Rose Hans M. Kristensen Simon Lunn Foreword by Ernest J. Moniz and Sam Nunn January 2018 The views expressed in this publication are the authors’ own and do not necessarily reflect those of NTI, its Board of Directors, or other institutions with which the authors are associated. © 2018 Nuclear Threat Initiative All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission of the publisher and copyright holder. -

The Future of US Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons and Implications for NATO

The Future of U.S. Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons and Implications for NATO Drifting Toward the Foreseeable Future Jeffrey A. Larsen, Ph.D. A report prepared in accordance with the requirements of the 2005-06 NATO Manfred Wörner Fellowship for NATO Public Diplomacy Division 31 October 2006 UNCLASSIFIED US NSNW and Implications for NATO Larsen ii US NSNW and Implications for NATO Larsen Table of Contents List of Figures vii List of Tables vii Foreword ix Methodology x Disclaimer x Executive Summary xi I. Introduction 1 Background to Today’s Situation 2 Defining Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons 6 Findings 8 II. Historical Background 11 Historical Summary of Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons in Europe 12 Recurrent Themes in Alliance Nuclear History 16 Modernization Episodes in Europe 21 The Nuclear Planning Group 22 The High Level Group 23 The Montebello Decision and SNF Modernization 25 The End of the Cold War 27 The Presidential Nuclear Initiatives 30 Russian Response to the PNIs 33 Arms Control and Relations with Russia in the 1990s 35 Key Nuclear Documents 37 Summary 38 III. Is There a Future for Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons? 39 Recent Developments 40 Current Status of NSNW in States of Interest 42 United States 42 Russia 46 Issues Regarding NSNW 48 Arguments For and Against Future Roles for NSNW 49 Arguments For 49 Arguments Against 50 Future Roles for Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons 51 Political 51 Extended Deterrence 51 Arms Control 52 Military 52 Escalation Dominance 52 Target Coverage 53 Counter NBC 54 Supporting the Strategic Nuclear Arsenal 54 Robustness 54 iii US NSNW and Implications for NATO Larsen Hedging 54 Summary 55 IV. -

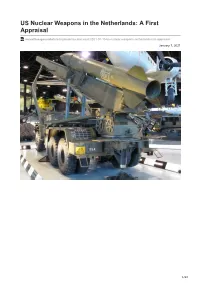

US Nuclear Weapons in the Netherlands: a First Appraisal

US Nuclear Weapons in the Netherlands: A First Appraisal nsarchive.gwu.edu/briefing-book/nuclear-vault/2021-01-15/us-nuclear-weapons-netherlands-first-appraisal January 7, 2021 1/22 During the Cold War, Dutch units had responsibility for nuclear-capable Honest John rockets that were deployed in West Germany. This is an Honest John on display in the National Military Museum at the site of the former airbase at Soesterberg. (Photo from Wikipedia Commons). Published: Jan 15, 2021 Briefing Book #736 Edited by Cees Wiebes and William Burr For more information, contact: 202-994-7000 or [email protected] January 1960 Agreement Led to Nuclear Sharing Arrangements Public Access to Key Historical Records in Doubt after Dutch Courts Affirm Secrecy Regime for U.S. Nukes Washington, D.C., January 15, 2021 – The stationing of U.S. nuclear weapons in Europe remains a controversial issue on both sides of the Atlantic. One of the less well- known cases involves the Netherlands, which first accepted atomic weapons shortly after the two governments signed a secret stockpile agreement in January 1960. That accord is part of a compilation of declassified documents posted today – most for the first time – by the National Security Archive. 2/22 That the U.S. has authorized deployments to numerous NATO states is one of those secrets everybody knows – Dutch former Prime Minister Ruud Lubbers acknowledged the facts of the matter involving his own country in 2013. Nevertheless, the arrangements are an official secret, as is the number of weapons currently in the Netherlands, and obtaining access to the historical record is a major challenge for historians. -

Withdrawal Issues What NATO Countries Say About the Future of Tactical Nuclear Weapons in Europe

Withdrawal Issues What NATO countries say about the future of tactical nuclear weapons in Europe Susi Snyder & Wilbert van der Zeijden March 2011 Acronyms used in this report DCA- dual capable aircraft NAC- North Atlantic Council NATO- North Atlantic Treaty Organisation NPG- Nuclear Planning Group NPT- Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty WS3- Weapons Storage and Security System TNW- tactical nuclear weapons NoNukes is IKV Pax Christi’s campaign for a world free of nuclear weapons. IKV Pax Christi is the joint peace organization of the Dutch Interchurch Peace Council (IKV) and Pax Christi Netherlands. We work for peace, reconciliation and justice in the world. We join with people in conflict areas to work on a peaceful and democratic society. We enlist the aid of people in the Netherlands who, like IKV Pax Christi, want to work for political solutions to crises and armed conflicts. IKV Pax Christi combines knowledge, energy and people to attain one single objective: there must be peace! The NoNukes campaign informs, mobilizes and speaks out for nuclear disarmament. We do so through research, publications, political and public advocacy. The written contents of this booklet may be quoted or reproduced, provided that the source of the information is acknowledged. IKV Pax Christi would like to receive a copy of the document in which this report is quoted. You can stay informed about NoNukes publications and activities by subscribing to our newsletter. To subscribe, or to receive additional copies of this report, please send your request to [email protected]. Authors Susi Snyder is the Nuclear Disarmament Programme Leader for IKV Pax Christi. -

ITALY's NUCLEAR CHOICES Leopoldo Nuti

UNISCI Discussion Papers, Nº 25 (January / Enero 2011) ISSN 1696-2206 ITALY’S NUCLEAR CHOICES Leopoldo Nuti 1 University of Roma Tre Abstract: Italy’s military nuclear policy throughout the Cold War was an attempt to foster the country’s aspirations to a position of parity among the other European powers. The issue of its own rank and collocation in the international hierarchy of powers had been central in its foreign policy since the birth of the country, and the new generation of politicians that shaped Italian foreign policy after the Second World was no less aware of this critical factor than their predecessors. The nuclearization of NATO made it inevitable that only those countries which had access to nuclear weapons would ultimately make the crucial decisions for the future of the alliance. The Italian government reached the conclusion that its only way to a nuclear status of some sorts would be through a close cooperation with NATO and the USA. Between 1955 and 1959, the acceptance of US nuclear weapons on Italian soil eventually evolved into a pattern that formed the basis for Italian nuclear policies for the next 10 years or so. Italy was very reluctant to ratify the NPT and this led to a strong behind the scenes alliance with the other main Western European opponents, the Federal Republic of Germany and a wide ranging series of contacts with all the other possible opponents to the treaty, from Japan to India. In 1979, Italy accepted the new Euromissiles on its territory. Again, Italy considered nuclear weapons as its winning card and the tool has to be used to shorten the gap with the other major European partners. -

December 2020 © Author, December 2020

ͳͳͲ BELGIUM SHOULD NOT CHANGE STRATEGY ON HER CONTRIBUTION TO NATO’S NUCLEAR ROLE SHARING DIDIER AUDENAERT ʹͲʹͲ ABOUT THE AUTHOR Col. (Ret.) Didier Audenaert is a Senior Associate Fellow at the Egmont – Royal Insti- tute for International Relations in Brussels. Previously, he served for 4 years as NATO expert advisor at Belgian Foreign Affairs and before that for 6 years as Defence Coun- sellor to the Belgian NATO Delegation. He also worked for almost 4 years at NATO Defense College. ABOUT THE EGMONT PAPERS The Egmont Papers are published by Egmont – The Royal Institute for International Relations. Founded in 1947 by eminent Belgian political leaders, Egmont is an inde- pendent think-tank based in Brussels. Its interdisciplinary research is conducted in a spirit of total academic freedom. A platform of quality information, a forum for debate and analysis, a melting pot of ideas in the field of international politics, Egmont’s ambition – through its publications, seminars and recommendations – is to make a useful contribution to the decision-making process. Table of Contents Introduction / Executive summary . 2 Many challenges in the European security environment . 2 NATO’s deterrence: aggression of any kind is not a rational option . 3 NATO’s “collective defence”: one for all and all for one . 4 Allies remain committed to arms control, non-proliferation and disarmament . 5 NATO’s Nuclear Planning Group (NPG) . 6 NATO’s Nuclear Forces. 6 1. “La France ne dépend d’aucune autre puissance pour ce qui est de sa sécurité” . 7 2. UK: “a nuclear deterrent to autonomously protect the UK”.