December 2020 © Author, December 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unclassified 1 House Armed Services Committee On

UNCLASSIFIED HOUSE ARMED SERVICES COMMITTEE ON STRATEGIC FORCES STATEMENT OF CHARLES A. RICHARD COMMANDER UNITED STATES STRATEGIC COMMAND BEFORE THE HOUSE ARMED SERVICES COMMITTEE ON STRATEGIC FORCES 21 APRIL 2021 HOUSE ARMED SERVICES COMMITTEE ON STRATEGIC FORCES 1 UNCLASSIFIED INTRODUCTION United States Strategic Command (USSTRATCOM) is a global warfighting command, and as the Commander, I am privileged to lead the 150,000 Sailors, Soldiers, Airmen, Marines, Guardians, and Civilians who dedicate themselves to the Department of Defense’s highest priority mission. I thank the President, Secretary of Defense Austin, and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs Milley for their continued leadership in this vital mission area. The command is focused on and committed to the Secretary of Defense priorities to defend the nation, take care of our people, and succeed through teamwork. I also thank Congress for your continued support to ensure USSTRATCOM is equipped with the required resources necessary to achieve strategic deterrence in any situation on behalf of the nation. USSTRATCOM enables Joint Force operations and is the combatant command responsible for Strategic Deterrence, Nuclear Operations, Nuclear Command, Control, and Communications (NC3) Enterprise Operations, Joint Electromagnetic Spectrum Operations, Global Strike, Missile Defense, Analysis and Targeting, and Missile Threat Assessment. Our mission is to deter strategic attack and employ forces as directed, to guarantee the security of the nation and assure our allies and partners. The command has three priorities. First, above all else, we will provide strategic deterrence for the nation and assurance of the same to our allies and partners. Second, if deterrence fails, we are prepared to deliver a decisive response, decisive in every possible way. -

NATO and the Frameworks of Nuclear Non-Proliferation and Disarmament

NATO and the Frameworks of Nuclear Non-proliferation and Disarmament: Challenges for the for 10th and Disarmament: Challenges Conference NPT Review Non-proliferation of Nuclear and the Frameworks NATO Research Paper Tim Caughley, with Yasmin Afina International Security Programme | May 2020 NATO and the Frameworks of Nuclear Non-proliferation and Disarmament Challenges for the 10th NPT Review Conference Tim Caughley, with Yasmin Afina with Yasmin Caughley, Tim Chatham House Contents Summary 2 1 Introduction 3 2 Background 5 3 NATO and the NPT 8 4 NATO: the NPT and the TPNW 15 5 NATO and the TPNW: Legal Issues 20 6 Conclusions 24 About the Authors 28 Acknowledgments 29 1 | Chatham House NATO and the Frameworks of Nuclear Non-proliferation and Disarmament Summary • The 10th five-yearly Review Conference of the Parties to the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (the NPT) was due to take place in April–May 2020, but has been postponed because of the COVID-19 pandemic. • In force since 1970 and with 191 states parties, the NPT is hailed as the cornerstone of a rules-based international arms control and non-proliferation regime, and an essential basis for the pursuit of nuclear disarmament. But successive review conferences have been riven by disagreement between the five nuclear weapon states and many non-nuclear weapon states over the appropriate way to implement the treaty’s nuclear disarmament pillar. • Although the number of nuclear weapons committed to NATO defence has been reduced by over 90 per cent since the depths of the Cold War, NATO nuclear weapon states, and their allies that depend on the doctrine of extended nuclear deterrence for their own defence, favour continued retention of the remaining nuclear weapons until the international security situation is conducive to further progress on nuclear disarmament. -

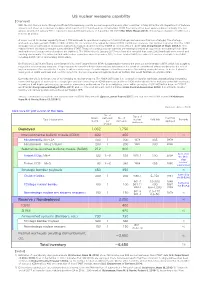

US Nuclear Weapons Capability 【Overview】 with the U.S

US nuclear weapons capability 【Overview】 With the U.S. there is more (though insufficient) transparency over its nuclear weapons than any other countries’. In May 2010, the U.S. Department of Defense issued a fact sheet on its nuclear stockpile, which reported 5,113 warheads as of September 2009. Ever since, it has been updated almost annually. The last update, provided in January 2017, reported a total 4,018 warheads as of September 30, 2016(The White House 2017), indicating a reduction of 1,095 over a seven‒year period. A closer look at its nuclear capability shows 1,750 warheads in operational deployment (1,600 strategic warheads and 150 non‒strategic). The strategic warheads are deployed with ICBMs, SLBMs and U.S. Air Force bases. The remainder (about 2,050) constitutes a reserve. This number is greater than the 1,393 strategic nuclear warheads in operational deployment registered under the New START as on September 1, 2017 (U.S. Department of State 2018‒1). One reason for the discrepancy may be due to the New START Treaty of counting only one warhead per strategic bomber, as opposed to accounting for all other warheads stored on base where bombers are stationed. The White House’s January 2017 fact sheet also revealed that some 2,800 warheads were retired and awaiting disassembly. It is estimated that, with further reductions since September 2017 to have totaled 3,800, the entire U.S. nuclear stockpile to be 6,450 including 2,650 retired and awaiting disassembly. On February 2, 2018, the Trump administration’s Nuclear Posture Review (NPR) fundamentally reversed the previous administration’s NPR, which had sought to reduce the role of nuclear weapons. -

S&TR March 2012 6 Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

S&TR March 2012 Extending the Life of an Aging Weapon 6 Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory S&TR March 2012 W78 Life-Extension Program Extending the Life of an Aging Weapon Stockpile stewards By law, the directors of the NNSA the warhead’s nonnuclear components. weapons laboratories—Lawrence The announcement was made in a letter Livermore, Los Alamos, and Sandia— from Don Cook, deputy administrator for modernize the W78 provide the secretaries of Energy and NNSA’s Defense Programs. Defense with an annual assessment of the The W78 is used on U.S. Air Force stockpile. Confidence in these assessments Minuteman III intercontinental ballistic warhead for the depends on the laboratories’ abilities to missiles (ICBMs). The Mark 12A reentry evaluate the inevitable changes that occur vehicle encloses the warhead to protect nation’s land-based inside nuclear weapons as they age and it from heat as it speeds through the to effectively deal with any safety or atmosphere. A team of about 30 Livermore performance issues that may arise from physicists, engineers, and chemists are intercontinental ballistic those changes. Stockpile stewardship working on an options study in what is activities enhance understanding of currently planned to be a 10-year effort to nuclear weapons and ensure their safety extend the W78’s service life for another missiles. and performance through a combination 30 years. of theoretical advances, nonnuclear In Congressional testimony in 2011, experiments, supercomputer simulations, Laboratory Director George Miller (now OLLOWING the end of the Cold and stockpile surveillance. When retired) underscored the importance of FWar, the U.S. -

AMICUS CURIAE BRIEF of TRI-VALLEY Cares -0 Case No

Case4:14-cv-01885-JSW Document26 Filed08/20/14 Page1 of 5 1 SCOTT YUNDT (CSB #242595) TRI-VALLEY CARES 2 2582 Old First Street 3 Livermore, California 94550 Telephone: (925) 443-7148 4 Facsimile: (925) 443-0177 Email: [email protected] 5 6 Attorney for Amicus Curiae TRI-VALLEY COMMUNITIES 7 AGAINST A RADIOACTIVE ENVIRONMENT (CAREs) 8 9 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT 10 FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 11 SAN FRANCISCO DIVISION 12 13 ) Case No. 4:14-cv-01885-JSW THE REPUBLIC OF THE MARSHALL ) 14 ) ISLANDS, a non-nuclear-weapon State party ) MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF 15 to the Treaty on the Non Proliferation of ) AMICUS CURIAE OF TRI-VALLEY Nuclear Weapons, ) CAREs IN SUPPORT OF VENUE IN THE 16 ) NORTHERN DISTRICT COURT OF Plaintiffs, ) CALIFORNIA 17 ) v. ) 18 ) Hearing Date: September 12, 2014 ) Time: 9:00 A.M. 19 THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ) Courtroom: Oakland Courthouse, PRESIDENT BARACK OBAMA, THE ) 20 PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES ) Courtroom 5 – 2nd Floor, OF AMERICA; THE DEPARTMENT OF ) 1301 Clay Street 21 DEFENSE; SECRETARY CHARLES ) Oakland, CA 94612 ) 22 HAGEL, THE SECRETARY OF ) DEFENSE; THE DEPARTMENT OF ) 23 ENERGY; SECRETARY ERNEST MONIZ, ) THE SECRETARY OF ENERGY; AND 24 THE NATIONAL NUCLEAR SECURITY 25 ADMINISTRATION, 26 Defendants. 27 28 MOTION FOR LEAVE TO FILE BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE OF TRI-VALLEY CAREs -0 Case No. 4:14-CV-01885-JSW Case4:14-cv-01885-JSW Document26 Filed08/20/14 Page2 of 5 1 TO ALL PARTIES AND THEIR ATTORNEYS OF RECORD: 2 PLEASE TAKE NOTICE THAT Tri-Valley Communities Against a Radioactive 3 Environment (CAREs) hereby moves this Court for leave to file a brief as amicus curiae in the 4 above-captioned case in support the Plaintiff’s choice of venue in the Northern District Court of 5 California and to oppose dismissal based on that choice of venue. -

Not for Publication Until Released by Senate Armed Services Committee Strategic Forces Subcommittee United States Senate

NOT FOR PUBLICATION UNTIL RELEASED BY SENATE ARMED SERVICES COMMITTEE STRATEGIC FORCES SUBCOMMITTEE UNITED STATES SENATE DEPARTMENT OF THE AIR FORCE PRESENTATION TO THE SENATE ARMED SERVICES COMMITTEE- STRATEGIC FORCES SUBCOMMITTEE UNITED STATES SENATE SUBJECT: FY19 Posture for Department of Defense Nuclear Forces STATEMENT OF: General Robin Rand, Commander Air Force Global Strike Command April 11, 2018 NOT FOR PUBLICATION UNTIL RELEASED BY SENATE ARMED SERVICES COMMITTEE STRATEGIC FORCES SUBCOMMITTEE UNITED STATES SENATE Introduction Chairwoman Fischer, Ranking Member Donnelly and distinguished members of the committee, thank you for allowing me to come before you and represent over 34,000 Air Force Global Strike Command (AFGSC) Total Force Airmen. It is an honor to be here today, and I look forward to updating you on what the command has accomplished and where we are going. Air Force Global Strike Command Mission Air Force Global Strike Command is a warfighting command responsible for two legs of our nation’s nuclear triad and the nation’s nuclear command, control, and communications (NC3) capabilities while simultaneously accomplishing the conventional global strike mission. As long as nuclear weapons exist, the United States must deter attacks and maintain strategic stability, assure our allies, and hedge against an uncertain future. At AFGSC, we’re especially focused on today’s evolving world and tomorrow’s emerging threats. The command’s top priority is to ensure our nuclear arsenal is lethal, safe, and secure. This priority underlies every nuclear-related activity in AFGSC, and we must never fail in the special trust and confidence the American people have bestowed on our nuclear warriors. -

Report- Non Strategic Nuclear Weapons

Federation of American Scientists Special Report No 3 May 2012 Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons By HANS M. KRISTENSEN 1 Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons May 2012 Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons By HANS M. KRISTENSEN Federation of American Scientists www.FAS.org 2 Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons May 2012 Acknowledgments e following people provided valuable input and edits: Katie Colten, Mary-Kate Cunningham, Robert Nurick, Stephen Pifer, Nathan Pollard, and other reviewers who wish to remain anonymous. is report was made possible by generous support from the Ploughshares Fund. Analysis of satellite imagery was done with support from the Carnegie Corporation of New York. Image: personnel of the 31st Fighter Wing at Aviano Air Base in Italy load a B61 nuclear bomb trainer onto a F-16 fighter-bomber (Image: U.S. Air Force). 3 Federation of American Scientists www.FAS.org Non-Strategic Nuclear Weapons May 2012 About FAS Founded in 1945 by many of the scientists who built the first atomic bombs, the Federation of American Scientists (FAS) is devoted to the belief that scientists, engineers, and other technically trained people have the ethical obligation to ensure that the technological fruits of their intellect and labor are applied to the benefit of humankind. e founding mission was to prevent nuclear war. While nuclear security remains a major objective of FAS today, the organization has expanded its critical work to issues at the intersection of science and security. FAS publications are produced to increase the understanding of policymakers, the public, and the press about urgent issues in science and security policy. -

Turkey, NATO & and Nuclear Sharing

Arms Control Association (ACA) British American Security Information Council (BASIC) Institute for Peace Research and Security Policy at the University of Hamburg (IFSH) Nuclear Policy Paper No. 5 April 2011 1 Mustafa Kibaroglu Turkey, NATO & and Nuclear Sharing: Prospects after NATO's Lisbon Summit In the run-up to the Lisbon summit meeting of NATO on November 19-20, 2010, where the new Strategic Concept of the alliance was adopted, the status of U.S. tactical nuclear weapons deployed in five European countries, namely Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Turkey was a significant topic of debate, and remains so afterwards. Some have suggested the speedy withdrawal of these weapons while others have endorsed their extended stay on the continent for as long as there are nuclear threats to the alliance.2 Turkey, as a host, has long been supportive changes in the deployment of theater of retaining U.S. nuclear weapons on its nuclear weapons in other NATO states is territory for various reasons and also more doubtful. expected others to continue to deploy these weapons as part of the burden sharing and This being the case for the allied countries solidarity principles of the alliance. Turkey in general, and from Turkey’s perspective in believes that the presence of U.S. nuclear particular, this paper will present primarily weapons in Europe strengthens the U.S. the views in the political, diplomatic, and commitment to transatlantic security, and military circles in Turkey with respect to the contributes to the credibility of the extended prolonged deployment of the U.S. -

NATO and Nuclear Disarmament

North Atlantic Treaty Organization www.nato.int/factsheets Factsheet October 2020 NATO and Nuclear Disarmament NATO Allies are strongly committed to arms control, disarmament, and non-proliferation, which play an important role in preserving peace in the Euro-Atlantic region. NATO actively contributes to effective and verifiable nuclear disarmament efforts through its policies and activities, and the commitments of its member countries. Allies recognise the threat posed by weapons of mass destruction (WMD), as well as their means of delivery, by state and non-state actors. NATO designs its partnership programmes to provide effective frameworks for dialogue, consultation, and coordination on a wide range of arms control-related issues, including nuclear disarmament. NATO’s Role in Nuclear Disarmament Disarmament is the act of eliminating or abolishing weapons, either unilaterally or reciprocally. It may refer either to reducing and limiting the number and types of arms, or to eliminating entire categories of weapons. NATO’s policies in this field support consultation and practical cooperation on nuclear policy issues, including arms control, disarmament, and non-proliferation. NATO supports and facilitates policy-making among members, and consultations with partners and other countries, and aids in the implementation of international obligations. All NATO Allies are parties to the most important of the global treaties on WMD, such as the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), the Chemical Weapons Convention, and the Biological and Toxin Weapons Convention. NATO consults and cooperates with relevant international organizations, including the UN Office for Disarmament Affairs, the African Union, the League of Arab States, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, and the European Union. -

Nuclear Matters. a Practical Guide 5B

NUCLEAR MATTERS A Practical Guide Form Approved Report Documentation Page OMB No. 0704-0188 Public reporting burden for the collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington VA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to a penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if it does not display a currently valid OMB control number. 1. REPORT DATE 3. DATES COVERED 2. REPORT TYPE 2008 00-00-2008 to 00-00-2008 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5a. CONTRACT NUMBER Nuclear Matters. A Practical Guide 5b. GRANT NUMBER 5c. PROGRAM ELEMENT NUMBER 6. AUTHOR(S) 5d. PROJECT NUMBER 5e. TASK NUMBER 5f. WORK UNIT NUMBER 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION Office of the Deputy Assistant to the Secretary of Defense (Nuclear REPORT NUMBER Matters),The Pentagon Room 3B884,Washington,DC,20301-3050 9. SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 10. SPONSOR/MONITOR’S ACRONYM(S) 11. SPONSOR/MONITOR’S REPORT NUMBER(S) 12. DISTRIBUTION/AVAILABILITY STATEMENT Approved for public release; distribution unlimited 13. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES 14. ABSTRACT 15. SUBJECT TERMS 16. SECURITY CLASSIFICATION OF: 17. -

NATO Nuclear Deterrence

North Atlantic Treaty Organization www.nato.int/factsheets Factsheet February 2020 NATO Nuclear Deterrence Nuclear deterrence has been at the core of NATO’s collective defence for 70 years. In an uncertain world, nuclear weapons continue to play a critical role in NATO’s deterrence and defence. The purpose of NATO’s nuclear capability is to preserve peace, prevent coercion, and deter aggression. Nuclear weapons are unique, and the circumstances in which NATO might contemplate the use of them are extremely remote. However, if the fundamental security of any Ally were to be threatened, NATO has the capabilities and resolve to defend itself – including with nuclear weapons. NATO is committed to creating the conditions for a world without nuclear weapons, in line with Allies’ commitments to the Non-Proliferation Treaty. Since the end of the Cold War, the number of nuclear weapons available to NATO in UK MOD - Crown Copyright Europe has been reduced dramatically, by around 90 percent. However, as long as nuclear weapons exist, NATO will remain a nuclear Alliance and Allies will continue to take all steps necessary to ensure NATO’s nuclear deterrent remains safe, secure and effective. Nuclear Forces Three NATO members - the United States, France and the United Kingdom – have nuclear weapons. The strategic forces of the Alliance, particularly those of the United States, are the supreme guarantee of the Alliance’s security. The independent strategic nuclear forces of the United Kingdom and France have a deterrent role of their own and contribute significantly to the overall security of the Alliance. NATO’s nuclear deterrence also relies on US nuclear weapons deployed in Europe and supporting capabilities and infrastructure provided by Allies. -

Building a Safe, Secure, and Credible NATO Nuclear Posture

Building a Safe, Secure, and Credible NATO Nuclear Posture NUCLEAR THREAT INITIATIVE 1776 Eye St, NW | Suite 600 | Washington DC 20006 www.nti.org Steve Andreasen, Isabelle Williams, Brian Rose, @NTI_WMD Hans M. Kristensen, and Simon Lunn www.facebook.com/nti.org Foreword by Ernest J. Moniz and Sam Nunn ABOUT THE NUCLEAR THREAT INITIATIVE The Nuclear Threat Initiative works to protect our lives, environment, and quality of life now and for future generations. We work to prevent catastrophic attacks with weapons of mass destruction and disruption (WMDD)—nuclear, biological, radiological, chemical, and cyber. Founded in 2001 by former U.S. Senator Sam Nunn and philanthropist Ted Turner, who continue to serve as co-chairs, NTI is guided by a prestigious, international board of directors. Ernest J. Moniz serves as chief executive officer and co-chair; Des Browne is vice chair; and Joan Rohlfing serves as president. www.nti.org Cover: A Dutch F-16 takes off from Leeuwarden Airbase in the Netherlands in 2011. PHOTO BY ROBIN UTRECHT/AFP/GETTY IMAGES Building a Safe, Secure, and Credible NATO Nuclear Posture Steve Andreasen Isabelle Williams Brian Rose Hans M. Kristensen Simon Lunn Foreword by Ernest J. Moniz and Sam Nunn January 2018 The views expressed in this publication are the authors’ own and do not necessarily reflect those of NTI, its Board of Directors, or other institutions with which the authors are associated. © 2018 Nuclear Threat Initiative All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission of the publisher and copyright holder.