James W. Orr, Saint John, New Brunswick, 1936-2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Canada's Location in the World System: Reworking

CANADA’S LOCATION IN THE WORLD SYSTEM: REWORKING THE DEBATE IN CANADIAN POLITICAL ECONOMY by WILLIAM BURGESS BA (Hon.), Queens University, 1978 MA (Plan.), University of British Columbia, 1995 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES Department of Geography We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ __ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA January 2002 © William Burgess, 2002 Abstract Canada is more accurately described as an independent imperialist country than a relatively dependent or foreign-dominated country. This conclusion is reached by examining recent empirical evidence on the extent of inward and outward foreign investment, ownership links between large financial corporations and large industrial corporations, and the size and composition of manufacturing production and trade. -

Proquest Dissertations

POLICY, ADVOCACY AND THE PRESS: ECONOMIC NATIONALISM IN SOUTHERN ONTARIO 1968-1974 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Guelph by DAVID BUSSELL In partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts September, 2010 © David Bussell, 2010 Library and Archives Bibliothdque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de l'6dition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-71461-4 Our file Notre inference ISBN: 978-0-494-71461-4 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non- support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Trudeau's Political Philosophy

TRUDEAU'S POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY: ITS IMPLICATIONS FOR LIBERTY AND PROGRESS by John L. Hiemstra A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree Master of Philosophy The Institute for Christian Studies Toronto, Ontario ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank Dr. Bernard Zylstra for his assistance as my thesis supervisor, and Citizens for Public Justice for the grant of a study leave to enable me to complete the writing of this thesis. TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE...................................................... 2 I. BASIC ASSUMPTIONS.................................... 6 A. THE PRIMACY OF THE INDIVIDUAL...................... 6 1. The Individual as Rational....................... 9 2. The Individual and Liberty....................... 11 3. The Individual and Equality...................... 13 B. ETHICS AS VALUE SELECTION.......................... 14 C. HISTORY AS PROGRESS.................................. 16 D. PHILOSOPHY AS AUTONOMOUS............................ 19 II. THE INDIVIDUAL AND THE STATE....................... 29 A. SOCIETY AND STATE.................................... 29 B. JUSTICE AS PROCEDURE................................. 31 C. DEFINING THE COMMON GOOD IN A PROCEDURAL JUSTICE STATE......................................... 35 1. Participation and Democracy....................... 36 2. Majority Mechanism.................................. 37 D. PRELIMINARY QUESTIONS................................ 39 III. THE DISEQUILIBRIUM OF NATIONALISM................. 45 A. THE STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM...................... -

After Left Nationalism: the Future of Canadian Political Economy April 30, 2003 by Paul Kellogg Paper Presented to the 2003 Meet

After Left Nationalism: The Future of Canadian Political Economy April 30, 2003 By Paul Kellogg Paper presented to the 2003 meetings of the Canadian Political Science Association, Halifax, Nova Scotia Draft only / Not for quotation Comments to [email protected] INTRODUCTION .............................................................................1 INHERENTLY ANTI-CAPITALIST? ........................................................2 A FAILED ‘PARADIGM SHIFT’.............................................................5 CHART 1 – DECLINE OF RESOURCE SHARE, 1926-1976 ................................................7 CHART 2 – RESOURCES AS A PERCENT OF GDP, CANADA AND THE US, 1987-2001 ........8 CHART 3 – MANUFACTURING AS A PERCENT OF GDP, CANADA AND THE US, 1987-2001........................................................................ 10 CHART 4 – MOTOR VEHICLE AND PARTS PRODUCTION AS A PERCENT OF ALL MANUFACTURING PRODUCTION,CANADA AND THE US, 1987-2001 ..................................................................................... 14 CHART 5 – MOTOR VEHICLE AND OTHER TRANSPORTATION PRODUCTION AS A PERCENT OF ALL MANUFACTURING PRODUCTION, CANADA AND THE US, 1987-2001 ..................................................................................... 15 IMPRESSIONISM AND THE LEGACY OF DEAD GENERATIONS .....................16 THE NATIONAL QUESTIONS IN CANADA...............................................20 THE WAY FORWARD ......................................................................22 NOTES........................................................................................26 -

The Liberal Party and the Canadian State Reg Whitaker

Document generated on 09/27/2021 9:56 p.m. Acadiensis The Liberal Party and the Canadian State Reg Whitaker Volume 12, Number 1, Autumn 1982 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/acad12_1rv06 See table of contents Publisher(s) The Department of History of the University of New Brunswick ISSN 0044-5851 (print) 1712-7432 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this document Whitaker, R. (1982). The Liberal Party and the Canadian State. Acadiensis, 12(1), 145–163. All rights reserved © Department of History at the University of New This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit Brunswick, 1982 (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ Reviews / Revues 145 The Liberal Party and the Canadian State The Liberal Party is a central enigma in the Canadian conundrum. The "government party" has been in office more than 80 per cent of the time since the First World War. In 24 general elections held in this century, the Conser vatives have gained more seats than the Liberals in only seven — and more votes than the Liberals in only five. For the last 100 years, the Liberals have had only five leaders, and each has been returned by the voters as prime minister at least twice, and one as many as five times. -

The Liberal Third Option

The Liberal Third Option: A Study of Policy Development A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fuliiment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Political Science University of Regina by Guy Marsden Regina, Saskatchewan September, 1997 Copyright 1997: G. W. Marsden 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON KI A ON4 Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Canada Canada Your hie Votre rdtérence Our ME Notre référence The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distibute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substanîial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. This study presents an analysis of the nationalist econornic policies enacted by the federal Liberal government during the 1970s and early 1980s. The Canada Development Corporation(CDC), the Foreign Investment Review Agency(FIRA), Petro- Canada(PetroCan) and the National Energy Prograrn(NEP), coliectively referred to as "The Third Option," aimed to reduce Canada's dependency on the United States. -

The Waffle, the New Democratic Party, and Canada's New Left During the Long Sixties

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-13-2019 1:00 PM 'To Waffleo t the Left:' The Waffle, the New Democratic Party, and Canada's New Left during the Long Sixties David G. Blocker The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Fleming, Keith The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in History A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © David G. Blocker 2019 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Canadian History Commons Recommended Citation Blocker, David G., "'To Waffleo t the Left:' The Waffle, the New Democratic Party, and Canada's New Left during the Long Sixties" (2019). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 6554. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/6554 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i Abstract The Sixties were time of conflict and change in Canada and beyond. Radical social movements and countercultures challenged the conservatism of the preceding decade, rejected traditional forms of politics, and demanded an alternative based on the principles of social justice, individual freedom and an end to oppression on all fronts. Yet in Canada a unique political movement emerged which embraced these principles but proposed that New Left social movements – the student and anti-war movements, the women’s liberation movement and Canadian nationalists – could bring about radical political change not only through street protests and sit-ins, but also through participation in electoral politics. -

Canadian Journal Ofpolitical and Social Theory/Revue Canadienne De Theone Politique Et Sociale, Vol

Canadian Journal ofPolitical and Social Theory/Revue canadienne de theone politique et sociale, Vol . 4, No. 1 (Winter/ Hiver, 1980) . REASON, PASSION AND INTEREST: PIERRE TRUDEAUS ETERNAL LIBERAL TRIANGLE Reginald Wfhitaker Considerable attention has been lavished over the years on Trudeau as the philosopher of federalism and bitter critic of Quebec nationalism. It is easy enough to assume, along with the Right and Left in English Canada and le tout-Quebec, that Trudeau's "rigidity" and "inflexibility" on these questions has simply left him as an anachronism, passed over by the rush of events and the seemingly inexorable advance of independantisme in Quebec and decentralist regionalism in English Canada. Yet nothing -is more notoriously ephemeral than political fortune. That Trudeau's ideas are presently in eclipse is apparent; that they are thereby exhausted is by no means obvious . It is a mark of the power of this man that no strong federalist position can in the near future escape the colour and quality which his expression has given to this thesis in the dialectics of centralization-decentralization and duality-separation. In this sense alone Trudeau's arguments bear continued reading: to a greater extent than many of us would like to admit, he remains close to the heart of our central dilemmas . It is not however this relatively familiar terrain which I propose to cover once again. Journalist Anthony Westell wrote a book on Trudeau called Paradox in Power, and that phrase perhaps best sums up a common reading of Trudeau, especially by English Canadian intellectuals. How could a man who first rose to notoriety in Duplessis' Quebec as a "radical" defender of strikers, a passionate proponent ofcivil liberties and a tireless advocate of democratization of public life turn into the prime minister who invoked the War Measures Act, defended ' This paper was originally presented, in slightly different form, at a symposium on the political thought of Pierre Trudeau, sponsored by the Department of Political Science at the University of Calgary, 19 October, 1979 . -

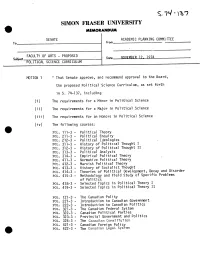

Simon FRASER UNIVERSITY MEMORANDUM

SiMON FRASER UNIVERSITY MEMORANDUM SENATE ACADEMIC PLANNING COMM1 TEE To I From FACULTY OF ARTS - PROPOSED Subject LITICAL SCIENCE CURRICULUM MOTION 1 That Senate approve, and recommend approval to the Board, the proposed Political Science Curriculum, as set forth in S. 74-137, including (i) The requirements for a Minor in Political Science (ii) The requirements for a Major in Political Science (iii) The requirements for an Honors in Political Science (iv) The following courses: POL. 111-3 - Political Theory POL. 211-3 - Political Enquiry POL. 212-3 - Political Ideologies POL. 311-3 - History of Political Thought I FOL. 312-3 - History of Political Thought II POL. 313-3 - Political Analysis POL. 314-3 - Empirical Political Theory POL. 411-3 - Normative Political Theory FOL. 412-3 - Marxist Political Theory FOL. 413-3 - History of Socialist Thought POL. 414-3 - Theories of Political Development, Decay and Disorder PaL. 415-3 - Methodology and Field Study of Specific Problems of Politics VOL. 418-3 - Selected Topics in Political Theory I POL. 419-3 - Selected Topics in Political Theory II POL. 121-3 - The Canadian Polity POL. 221-3 - Introduction to Canadian Government POL. 222-3 - Introduction to Canadian Politics POL. 321-3 - The Canadian Federal System POL. 322-3 - Canadian Political Parties POL. 323-3 - Provincial Government and Politics POL. 324-3 - The Canadian Constitution POL. 421-3 - Canadian Foreign Policy POL. 422-3 - The Canadian Legal System -2- POL. 423-3 - B.C. Government and Politics POL. 428-3 - Selected Topics in Canadian Government and Politics I POL. 429-3 - Selected Topics in Canadian Government and Politics II POL. -

The Course and Canon of Left Nationalism in English Canada, 1968-1979

The Course and Canon of Left Nationalism in English Canada, 1968-1979 by Michael Cesare Chiarello A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History with Specialization in Political Economy Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2020, Michael Cesare Chiarello ii Abstract This dissertation is an inquiry into the political and intellectual currents of English Canadian left nationalism from the late 1960s through the 1970s. It investigates the reasons why left nationalism emerged as a major force in English Canadian left politics and explores the evolution of a neo-Marxist critique of both Canadian capitalism and Canada's relationship with the United States. Left nationalism represented a distinctive perspective and political agenda. Its vision was of a Canada divorced from the American-led capitalist world system. English Canadian left nationalism had a political manifestation in the Waffle movement and an intellectual manifestation in the New Canadian Political Economy. The dissertation demonstrates that the left nationalist interpretation of Canadian- American relations was not rooted in anti-Americanism, but in a radical politics of democratic socialism and anti-imperialism. Left nationalism was primarily the product of neo-Marxist thought, rather than a reaction to problems in American politics, society, and foreign policy. English Canadian left nationalists were disruptors who, unlike their New Nationalist contemporaries, did not advance a program of capitalist or social democratic reform. The left nationalists were determined to replace capitalism with democratic socialism; without socialism, there could be no Canadian independence. Left nationalists sought to end Canada’s colonial status in the declining American empire, viewed the preservation of Canada’s resources as imperative to the country’s long-term prosperity, and advanced neo-Marxism in the academy and in the universities. -

Some Sidelights on Canadian Communist History

Some Sidelights on Canadian Communist History On Karen Levine’s 1977 Interviews During the summer of 2020 I happened to mention the Kenny oral history project to my friend Russell Hann, a labour historian with an encyclopedic memory and a well-organized personal archive. He immediately recalled a 1977 essay by a UofT undergraduate, Karen Levine, on the impact of the 1956 Khrushchev revelations on Canada’s Communists. He also recollected that she cited interviews she conducted with some important figures in the movement, including Robert Kenny. Russell promptly forwarded a copy of “The Labour Progressive Party in Crisis: 1956-57”i to me and after reading it, I contacted Karen, to find out if the recordings she made 43 years earlier still existed. Luckily, Karen kept them (with the unfortunate exception of J.B. Salsberg, a pivotal figure in the 1956 events) and generously agreed to add them to the other interviews in the Kenny oral archive. In her essay Karen also cited information gleaned from earlier recordings done by David Chud, one of several students who, in the early 1970s, recorded over 100 “interviews with individuals involved with [Canada’s] labour and socialist movements.” Don Lake, at that point associated with the left-nationalist Waffle wing of the New Democratic Party, was one of the graduate students who did these interviews. Today Don and his partner Elaine operate “D&E Books,” one of Toronto’s premier antiquarian bookstores. Their business was originally launched in 1977 as “October Books” after they purchased a stock of radical (and other) books and pamphlets from Peter Weinrich who was then in the process of winding up his partnership in Blue Heron Books. -

Who-Owns-Canada.Pdf

summary The Imperialist Nature of the PART 1: Who Controls the Economy? PART2: Canadian Bourgeoisie The concept of imperialism • Concentration and • Control of capital monopoly — The early 1900s — Concentration today • The strongholds of the Ca• nadian Bourgeoisie • Financial capital and the — Canadian giants in each financial oligarchy sector of the economy — The creation of Canadian finance capital at the — State corporations beginning of the 20th century — Canada's banks — Finance capital today — The financial oligarchy • The export of capital • The place of US imperialism — Who controls Canada's in the Canadian economy export of capital? — Fluctuations in US control — In which economic sectors — Tendency to decline since is Canadian foreign 1970 investment found? — The present state of US domination • The division of the world. — Canadian participation in the economic division of the world — Canada and the territorial • Who controls the strategic division of the world sectors of Canada's — The question of colonies economy? 8 9 Who owns Canada? Who controls the economy While other writers admit an independent Canadian —Canadian or foreign capitalists? bourgeoisie was able to develop, they insist that it This question has long been at the heart of quickly fell under US domination. debates among those who are committed to fighting Mel Watkins (4), for example, maintains that capitalism in our country. For by determining who around the turn of the century "the indigenous bour• controls economic and thus political power in Canada, geoisie dominates foreign capital and the state..."(5). we can identify the main enemy in our struggle for But the US rapidly turned Canada into a neo-colony.