ALBERTA in CONTEXT: Health Care Under NDP Governments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Debates Proceedings

Legislative Assembly of Manitoba DEBATES and PROCEEDINGS Speaker The Honourable Peter Fox Vol.XVlll No.98 2:30p.m., Monday, July5th, '1971. ThirdSession,29th Legislature. Printed by R. S. Evans - Queen's Printer for Province of Manitoba I I ELECTORAL DIVISION NAME ADDRESS ARTHUR J. Douglas Watt Reston, Manitoba ASSINIBOIA Steve Patrick 10 Red Robin Place, Winnipeg 12 BIRTLE-RUSSELL Harry E. Graham Binscarth, Manitoba BRANDON EAST Hon. Leonard S. Evans Legislative Bldg., Winnipeg 1 BRANDON WEST Edward McGill 2228 Princess Ave., Brandon, Man. BURROWS Hon. Ben Hanuschak Legislative Building, Winnipeg 1 CHARLESWOOD Arthur Moug 29 Willow Ridge Rd., Winnipeg 20 CHURCHILL Gordon Wilbert Beard 148 Riverside Drive, Thompson, Man. CRESCENTWOOD Cy Gonick 115 Kingsway, Winnipeg 9 DAUPHIN Hon. Peter Burtniak Legislative Bldg., Winnipeg 1 ELMWOOD Hon. Russell J. Doern Legislative Building, Winnipeg 1 EMERSON Gabriel Girard 25 Lamond Blvd., St. Boniface 6 FLIN FLON Thomas Barrow Cranberry Portage, Manitoba FORT GARRY L. R. (Bud) Sherman B6 Niagara St., Winnipeg 9 - FORT ROUGE Mrs. Inez Trueman 179 Oxford St., Winnipeg 9 GIMLI John C. Gottfried 44 - 3rd Ave., Gimli, Man. GLADSTONE James Robert Ferguson Gladstone, Manitoba INKSTER Hon. Sidney Green, O.C. Legislative Bldg., Winnipeg 1 KILDONAN Hon. Peter Fox 627 Prince Rupert Ave., Winnipeg 15 LAC DU BONNET Hon. Sam Uskiw Legislative Bldg., Winnipeg 1 LAKESIDE Harry J. Enns Woodlands, Manitoba LA VERENDRYE Leonard A. Barkman Box 130, Steinbach, Man. LOGAN William Jenkins 1287 Alexander Ave., Winnipeg 3 MINNEDOSA Walter Weir Room 250, Legislative Bldg., Winnipeg 1 MORRIS Warner H. Jorgenson Box 185, Morris, Man. OSBORNE Ian Turnbull 284 Wildwood Park, Winnipeg 19 PE MB INA George Henderson Manitou, Manitoba POINT DOUGLAS Donald Malinowski 361 Burrows Ave., Winnipeg 4 PORTAGE LA PRAIRIE Gordon E. -

Care for All

CARE FOR ALL WINNIPEG REGIONAL HEALTH AUTHORITY ANNUAL REPORT 2015 wrha.mb.ca Healthy People. Vibrant Communities. CARE FOR ALL. 2 WINNIPEG REGIONAL HEALTH AUTHORITY ANNUAL REPORT 2015 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL & ACCOUNTABILITY 5 PROFILE OF THE WINNIPEG REGIONAL HEALTH AUTHORITY 6 MESSAGE FROM THE BOARD CHAIR 8 MESSAGE FROM THE INTERIM PRESIDENT & CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER 10 VISION, MISSION, VALUES 2011-2016 12 STRATEGIC DIRECTIONS 16 COMMUNITY HEALTH ASSESSMENT 52 GOVERNANCE & ADMINISTRATION 53 Accreditation Status 53 Governance 54 Board of Directors Membership 55 Current & Outgoing Board Members 56 Public Sector Compensation Disclosure 58 Public Interest Disclosure (Whistleblower Protection) Act 58 Freedom of Information & Protection of Privacy Act (FIPPA) 60 French Language Services Report 61 Senior Executive Organizational Structure & Organizational Changes 64 STATISTICAL HIGHLIGHTS 65 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 73 Report of the Independent Auditors on the Summarized Consolidated Financial Statements 73 Summarized Consolidated Statement of Financial Position 74 Summarized Consolidated Statement of Operations 75 Budget Allocation by Sector and Major Expense 76 Administrative Costs Report 77 Administrative Costs and Percentages for the Region 78 Manitoba eHealth Operating Results 79 This icon will be used to throughout the report to identify information that is also available online. To find out more follow the link listed beside this icon. 4 WINNIPEG REGIONAL HEALTH AUTHORITY ANNUAL REPORT 2015 Letter of Transmittal & Accountability It is my pleasure to present the annual report of the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority for the fiscal year ended March 31, 2015. This annual report was prepared under the board’s direction, in accordance with The Regional Health Authorities Act and directions provided by the Minister of Health. -

88309 Rwanda Omslag

Assessment of the Impact and Influence of the Joint Evaluation of Emergency Assistance to Rwanda Lessons from Rwanda – Lessons for Today Rwanda – Lessons for Today Lessons from Following the 1994 Genocide in Rwanda the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs initiated a comprehensive evaluation of the international response. The findings were highly critical of nearly all the international actors. Ten years after the genocide the Ministry commissioned this assessment of the impact and influence of the evaluation. It concludes that the evaluation con- tributed to increased accountability among humanitarian organizations and that it had important influences on several major donor policies. But, despite a greater willingness by the international community to intervene militarily and to undertake more robust peacekeeping missions, these remain the exception rather than the rule where mass killings of civilians threaten or are even underway. The evaluation’s main conclusion – that “Humanitarian Action cannot substitute for political action” – remains just as December 2004 valid today as 10 years ago. Lessons from Rwanda – Lessons for Today ISBN: 87-7667-141-0 Lessons from Rwanda – Lessons for Today Assessment of the Impact and Influence of Joint Evaluation of Emergency Assistance to Rwanda John Borton and John Eriksson December 2004 © Ministry of Foreign Affairs December 2004 Production: Evaluation Department, Ministry of Foreign Affairs Cover: Kiure F. Msangi Graphic production: Phoenix-Print A/S, Aarhus, Denmark ISBN (report): 87-7667-141-0 e-ISBN (report): 87-7667-142-9 ISSN: 1399-4972 This report can be obtained free of charge by contacting: Danish State Information Centre Phone + 45 7010 1881 http://danida.netboghandel.dk/ The report can also be downloaded through the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ homepage www.um.dk or directly from the Evaluation Department’s homepage www.evaluation.dk Responsibility for the content and presentation of findings and recommendations rests with the authors. -

Tories Keep Lead, but Liberal-NDP Merger Could Change Status

For Immediate Release Canadian Public Opinion Poll Page 1 of 8 CANADIAN POLITICAL PULSE Tories Keep Lead, But Liberal-NDP Merger Could Change Status Quo A single centre-left party would provide a real challenge to the Conservatives, but only if it is led by Jack Layton or Bob Rae. [TORONTO – May 31, 2010] – The Conservative Party is holding on to a comfortable lead in KEY FINDINGS Canada's political scene, a new Angus Reid Public Opinion poll has found. ¾ Voting Intention: Con. 35%, Lib. 27%, NDP 19%, BQ 9%, Grn. 8%. The online survey of a representative national sample of 2,022 Canadians also looked at the ¾ Scenarios with a merged Liberal / NDP: way the electorate would behave in the event of a Six-point lead over the Tories under merger between the Liberal Party and the New Layton, Tie under Rae, Second place Democratic Party (NDP) under three different under Ignatieff prospective leaders. ¾ Approval Rating: Layton 30%, Harper Voting Intention 29%, Ignatieff 13%. Across the country, 35 per cent of decided voters ¾ Momentum: Layton -3, Harper -24, (unchanged since late April) would cast a ballot Ignatieff -28. for the Conservative candidate in their riding if a new federal election took place today. Full topline results are at the end of this release. The Liberal Party is second with 27 per cent (-1), From May 25 to May 27, 2010, Angus Reid Public Opinion conducted an online survey among 2,022 randomly selected just one point ahead of the proportion of the vote Canadian adults who are Angus Reid Forum panelists. -

Main Estimates Supplement 2021-2022 | Manitoba Health and Seniors Care

Budget 2021 Main Estimates Supplement Budgets complémentaires 2021/22 MANITOBA HEALTH SANTÉ ET SOINS AND SENIORS CARE AUX PERSONNES ÂGÉES MANITOBA MAIN ESTIMATES BUDGET SUPPLEMENT COMPLÉMENTAIRE 2021-2022 2021-2022 Department of Ministère de la Health and Seniors Care Santé et des Soins aux personnes âgées Minister’s Message and Executive Summary This document has been produced by Manitoba Health and Seniors Care as a supplement to the Printed Estimates of Expenditure. It is intended to provide background information on the department and complements the information already contained in the Printed Estimates of Expenditure. The contents of this document are organized into five parts. The first part provides an overview of the ministry including its strategy roadmap, strategic priorities, objectives and initiatives. The second part provides financial information on staffing and expenditures. The third part provides information on the amount of money the department requires, the spending and allocation plan, and how expenses will flow throughout the fiscal year. The fourth part provides a risk analysis overview. The fifth part provides the statutory responsibilities of the minister and a standard glossary of terms. Recently implemented across the Manitoba government, balanced scorecards foster operational improvements by reinforcing transparency, urgency, alignment and accountability. They have been added to the redesigned Supplement to identify key priorities for each department that staff will work towards, with appropriate performance measures. With the Supplement redesigned to be a business plan that focuses on strategic priorities, departments can then take steps to create operating plans that further identify how strategic priorities will translate into day-to-day operations. -

The 2006 Federal Liberal and Alberta Conservative Leadership Campaigns

Choice or Consensus?: The 2006 Federal Liberal and Alberta Conservative Leadership Campaigns Jared J. Wesley PhD Candidate Department of Political Science University of Calgary Paper for Presentation at: The Annual Meeting of the Canadian Political Science Association University of Saskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan May 30, 2007 Comments welcome. Please do not cite without permission. CHOICE OR CONSENSUS?: THE 2006 FEDERAL LIBERAL AND ALBERTA CONSERVATIVE LEADERSHIP CAMPAIGNS INTRODUCTION Two of Canada’s most prominent political dynasties experienced power-shifts on the same weekend in December 2006. The Liberal Party of Canada and the Progressive Conservative Party of Alberta undertook leadership campaigns, which, while different in context, process and substance, produced remarkably similar outcomes. In both instances, so-called ‘dark-horse’ candidates emerged victorious, with Stéphane Dion and Ed Stelmach defeating frontrunners like Michael Ignatieff, Bob Rae, Jim Dinning, and Ted Morton. During the campaigns and since, Dion and Stelmach have been labeled as less charismatic than either their predecessors or their opponents, and both of the new leaders have drawn skepticism for their ability to win the next general election.1 This pair of surprising results raises interesting questions about the nature of leadership selection in Canada. Considering that each race was run in an entirely different context, and under an entirely different set of rules, which common factors may have contributed to the similar outcomes? The following study offers a partial answer. In analyzing the platforms of the major contenders in each campaign, the analysis suggests that candidates’ strategies played a significant role in determining the results. Whereas leading contenders opted to pursue direct confrontation over specific policy issues, Dion and Stelmach appeared to benefit by avoiding such conflict. -

Mental Health Program Partnerships 2019 Group Name Primary Purpose

Mental Health Program Partnerships 2019 Group Name Primary Purpose Type of Engagement Contact Name and Info Info Feedback Joint Participant Sharing Planning Control Addictions Foundation of Manitoba To contribute to the health and well-being of Manitobans by Ben Fry CEO addressing the harm associated with addictions through 204-944-6200 education, prevention, rehabilitation and research. Collaborative X X X work focuses on co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders at a system level. Anxiety Disorders Association of Self-help organization committed to helping individuals who Mary Williams, Executive Director Manitoba struggle with anxiety disorders. Offers cognitive behavioural X 204-925-0600 groups, support groups and information. Block-by-Block Thunderwing Project The Block-by-Block Thunderwing project will bring multiple Pauline Jackson government and non-government agencies together, partnering to 204-938-7342 solve social problems in a 21-block, high-crime area of the North [email protected] X X X X End. This program is supported by the police, Manitoba Justice and a broad range of community-based agencies, helping families and the community become more resilient. CODI Program/River East & Transcona To provide enhanced consultation services on co-occurring Gale Colquhoun – CODI My Health My Health Team disorders to fee-for-service physicians signed on with the River X X X X Team Clinician East/Transcona My Health Team. [email protected] Coordinated Intake, Assessment & A coalition of organizations who support individuals who Brian Bechtel, Director, Winnipeg Triage Advisory Committee experience episodic or chronic homelessness. One goal is to Poverty Reduction Council (Doorways Project) create a single point of contact to assist individuals and those X X X 204-924-4295 supporting them to navigate supports as part of the Task Force Plan to End Homelessness. -

Debates Proceedings

Legislative Assembly of Manitoba DEBATES and PROCEEDINGS Speaker The Honourable Peter Fox Vol. XIX No. 76 10:00a.m., Friday, May 12tll, 1972. Fourth Session, 29th Legislature. Printed by R. S. Evans- Queen's Printer for Province of Manitoba Political Electoral Division Name Address Affiliation ARTHUR J. Douglas Watt P.C. Reston, Manitoba ASSINIBOIA Steve Patrick Lib. 10 Red Robin Place, Winnipeg 12 Bl RTLE-RUSSELL Harry E. Graham P.C. Binscarth, Manitoba BRANDON EAST Hon. Leonard S. Evans N.D.P. Legislative Bldg., Winnipeg 1 BRANDON WEST Edward McGill P.C. 2228 Princess Ave., Brandon, Man. BURROWS Hon. Ben Hanuschak N.D.P. Legislative Bldg., Winnipeg 1 CHARLESWOOD Arthur Moug P.C. 29 Willow Ridge Rd., Winnipeg 20 CHURCHILL Gordon Wilbert Beard lnd. 148 Riverside Drive, Thompson, Man. CRESCENTWOOD Cy Gonick N.D.P. 1- 174 Nassau Street, Winnipeg 13 DAUPHIN Hon. Peter Burtniak N.D.P. Legislative Bldg., Winnipeg 1 ELMWOOD Hon. RussellJ. Doern N.D.P. Legislative Bldg., Winnipeg 1 EMERSON Gabriel Girard P.C. 25 Lomond Blvd., St. Boniface 6 FLIN FLON Thomas Barrow N.D.P. Cranberry Portage, Manitoba FORT GARRY L. R. (Bud) Sherman P.C. 86 Niagara St., Winnipeg 9 FORT ROUGE Mrs. lnez Trueman P.C. 179 Oxford St., Winnipeg 9 GIMLI John C. Gottfried N.D.P. 44- 3rd Ave., Gimli Man. GLADSTONE James Robert Ferguson P.C. Gladstone, Manitoba INKSTER Sidney Green, Q.C. N.D.P. Legislative Bldg., Winnipeg 1 KILDONAN Hon. Peter Fox N.D.P. 244 Legislative Bldg., Winnipeg 1 LAC DU BONNET Hon. Sam Uskiw N.D.P. -

CCF) in New Brunswick, 1940-1949 Laurel Lewey

JOURNAL OF NEW BRUNSWICK STUDIES Issue 3 (2012) A Near Golden Age: The Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) in New Brunswick, 1940-1949 Laurel Lewey Abstract This history of the Cooperative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) in the 1940s in New Brunswick adds to a growing body of literature that challenges the misperception that the CCF scarcely existed east of Ontario. However, in spite of a host of historical (and later) social conditions that called out for the CCF, the 1940s was the only decade when the movement showed considerable promise in New Brunswick. This article will suggest that the failure of the movement to gain permanent traction was attributable to several factors: the political strength of the Liberal political machinery and Premier John B. McNair; anti-labour sentiments and the anti- CCF campaign in the media; organizational challenges within the party; social and economic conditions within the province; and the divergent agenda of Francophone and Anglophone New Brunswickers. Résumé Cette histoire de la Fédération du Commonwealth coopératif (FCC) dans les années 1940 au Nouveau-Brunswick s’ajoute aux nombreux écrits qui dénoncent la fausse perception que la FCC a rarement existé à l’est de l’Ontario. Toutefois, malgré une foule de conditions historiques, et plus tard sociales, qui ont favorisé la FCC, les années 1940 ont été la seule décennie pendant laquelle le mouvement a suscité un espoir considérable au Nouveau- Brunswick. Cet article démontrera que la faillite du mouvement à atteindre une croissance permanente était attribuable à plusieurs facteurs : la force de la machine politique du Parti libéral et du premier ministre John B. -

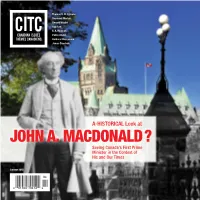

JOHN A. MACDONALD ? Seeing Canada's First Prime Minister in the Context of His and Our Times

Thomas H. B. Symons Desmond Morton Donald Wright Bob Rae E. A. Heaman Patrice Dutil Barbara Messamore James Daschuk A-HISTORICAL Look at JOHN A. MACDONALD ? Seeing Canada's First Prime Minister in the Context of His and Our Times Summer 2015 Introduction 3 Macdonald’s Makeover SUMMER 2015 Randy Boswell John A. Macdonald: Macdonald's push for prosperity 6 A Founder and Builder 22 overcame conflicts of identity Thomas H. B. Symons E. A. Heaman John Alexander Macdonald: Macdonald’s Enduring Success 11 A Man Shaped by His Age 26 in Quebec Desmond Morton Patrice Dutil A biographer’s flawed portrait Formidable, flawed man 14 reveals hard truths about history 32 ‘impossible to idealize’ Donald Wright Barbara Messamore A time for reflection, Acknowledging patriarch’s failures 19 truth and reconciliation 39 will help Canada mature as a nation Bob Rae James Daschuk Canadian Issues is published by/Thèmes canadiens est publié par Canada History Fund Fonds pour l’histoire du Canada PRÉSIDENT/PResIDENT Canadian Issues/Thèmes canadiens is a quarterly publication of the Association for Canadian Jocelyn Letourneau, Université Laval Studies (ACS). It is distributed free of charge to individual and institutional members of the ACS. INTRODUCTION PRÉSIDENT D'HONNEUR/HONORARY ChaIR Canadian Issues is a bilingual publication. All material prepared by the ACS is published in both The Hon. Herbert Marx French and English. All other articles are published in the language in which they are written. SecRÉTAIRE DE LANGUE FRANÇAISE ET TRÉSORIER/ MACDONALd’S MAKEOVER FRENch-LaNGUAGE SecRETARY AND TReasURER Opinions expressed in articles are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of Vivek Venkatesh, Concordia University the ACS. -

Discussion Following the Remarks of the Hon. Mr. Rae and Ambassador Giffin Proceedings of the Canada-United States Law Institute

Canada-United States Law Journal Volume 30 Issue Article 11 January 2004 Discussion following the Remarks of the Hon. Mr. Rae and Ambassador Giffin oceedingsPr of the Canada-United States Law Institute Conference on Multiple Actors in Canada-U.S. Relations: Multiple Issues, Multiple Actors - The Players in Canada-U.S. Relation Discussion Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/cuslj Part of the Transnational Law Commons Recommended Citation Discussion, Discussion following the Remarks of the Hon. Mr. Rae and Ambassador Giffin oceedingsPr of the Canada-United States Law Institute Conference on Multiple Actors in Canada-U.S. Relations: Multiple Issues, Multiple Actors - The Players in Canada-U.S. Relation, 30 Can.-U.S. L.J. 27 (2004) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/cuslj/vol30/iss/11 This Speech is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Canada-United States Law Journal by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. DISCUSSION FOLLOWING THE REMARKS OF THE HON. MR. RAE AND AMBASSADOR GIFFIN MR. GIFFIN: I have to respond to your point about your hope that our election will resolve some questions, I think our election has tried to resolve those very questions. I think there is a very vital debate going on between the President of the United States and the U.S. Senator who will be the De- mocratic nominee about our role in the world and whether or not it ought to be unilateral, multilateral, or whether it ought to engage the U.N. -

Hershell Ezrin Fonds University of Toronto Archives B2017-0021

University of Toronto Archives and Records Management Services Hershell E. Ezrin fonds B2017-0021 Daniela Ansovini, 2018 © University of Toronto Archives and Records Management Services 2018 Hershell Ezrin fonds University of Toronto Archives B2017-0021 Contents Biographical note ..................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and content ................................................................................................................... 4 Series 1: Personal and biographical....................................................................................... 6 Series 2: Correspondence ....................................................................................................... 7 Series 3: Addresses and presentations .................................................................................. 7 Series 4: Professional activity ................................................................................................... 8 Series 5: Photographs ............................................................................................................... 8 Series 6: Editorial cartoons ....................................................................................................... 9 Series 7: Collected bibliographic material............................................................................ 9 Appendix ................................................................................................................................