140903 CERRE Railfreight Discussion Paper 41/52

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genesee & Wyoming Inc. 2016 Annual Report

Genesee & Wyoming Inc. 2016 Annual Report Genesee & Wyoming Inc.*owns or leases 122 freight railroads worldwide that are organized into 10 operating regions with approximately 7,300 employees and 3,000 customers. * The terms “Genesee & Wyoming,” “G&W,” “the company,” “we,” “our,” and “us” refer collectively to Genesee & Wyoming Inc. and its subsidiaries and affiliated companies. Financial Highlights Years Ended December 31 (In thousands, except per share amounts) 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 Statement of Operations Data Operating revenues $874,916 $1,568,643 $1,639,012 $2,000,401 $2,001,527 Operating income 190,322 380,188 421,571 384,261 289,612 Net income 52,433 271,296 261,006 225,037 141,096 Net income attributable to Genesee & Wyoming Inc. 48,058 269,157 260,755 225,037 141,137 Diluted earnings per common share attributable to Genesee & Wyoming Inc. common stockholders: Diluted earnings per common share (EPS) $1.02 $4.79 $4.58 $3.89 $2.42 Weighted average shares - Diluted 51,316 56,679 56,972 57,848 58,256 Balance Sheet Data as of Period End Total assets $5,226,115 $5,319,821 $5,595,753 $6,703,082 $7,634,958 Total debt 1,858,135 1,624,712 1,615,449 2,281,751 2,359,453 Total equity 1,500,462 2,149,070 2,357,980 2,519,461 3,187,121 Operating Revenues Operating Income Net Income Diluted Earnings ($ In Millions) ($ In Millions) ($ In Millions) 421.61,2 Per Common Share 2 2,001.5 401.6 1 $2,000 2,000.4 $400 394.12 $275 271.3 $5.00 1 2 4.79 1 374.3 1 380.21 384.3 261.0 4.581 1,800 250 4.50 350 1,639.0 225.01 225 2 1 1,600 233.5 4.00 2 3.89 1,568.6 4.10 2 300 2 200 213.9 213.3 2 3.78 2 1,400 1 3.50 3.69 289.6 183.32 3.142 250 175 1,200 3.00 211. -

Affiliate Rewards Eligible Companies

Affiliate Rewards Eligible Companies Program ID's: 2012MY 2013MY 2014MY Designated Corporate Customer 28HCR 28HDR 28HER Fleet Company 28HCH 28HDH 28HEH Supplier Company 28HCJ 28HDJ 28HEJ Company Name Type 3 Point Machine SUPPLIER 3-D POLYMERS SUPPLIER 3-Dimensional Services SUPPLIER 3M Employee Transportation & Travel FLEET 84 Lumber Company DCC A & R Security Services, Inc. FLEET A B & W INC SUPPLIER A D E SUPPLIER A G Manufacturing SUPPLIER A G Simpson Automotive Inc SUPPLIER A I M CORPORATION SUPPLIER A M G INDUSTRIES INC SUPPLIER A T KEARNEYINC SUPPLIER A&D Technology Inc SUPPLIER A&E Television Networks DCC A. Raymond Tinnerman Automotive Inc SUPPLIER A. Schulman Inc SUPPLIER A.J. Rose Manufacturing SUPPLIER A.M Community Credit Union DCC A-1 SPECIALIZED SERVICES SUPPLIER AAA East Central DCC AAA National SUPPLIER AAA Ohio Auto Club DCC AARELL COMPANY SUPPLIER ABA OF AMERICA INC SUPPLIER ABB, Inc. FLEET Abbott Ball Co SUPPLIER ABBOTT BALL COMPANY THE SUPPLIER Abbott Labs FLEET Abbott, Nicholson, Quilter, Esshaki & Youngblood P DCC Abby Farm Supply, Inc DCC ABC GROUP-CANADA SUPPLIER ABC Widgit Company SUPPLIER Abednego Environmental Services SUPPLIER Abercrombie & Fitch FLEET Affiliate Rewards Eligible Companies Program ID's: 2012MY 2013MY 2014MY Designated Corporate Customer 28HCR 28HDR 28HER Fleet Company 28HCH 28HDH 28HEH Supplier Company 28HCJ 28HDJ 28HEJ ABERNATHY INDUSTRIAL SUPPLIER ABF Freight System Inc SUPPLIER ABM Industries, Inc. FLEET AboveNet FLEET ABP Induction SUPPLIER ABRASIVE DIAMOND TOOL COMPANY SUPPLIER Abraxis Bioscience Inc. FLEET ABSO-CLEAN INDUSTRIES INC SUPPLIER ACCENTURE SUPPLIER Access Fund SUPPLIER Acciona Energy North America Corporation FLEET Accor North America FLEET Accretive Solutions SUPPLIER Accu-Die & Mold Inc SUPPLIER Accumetric, LLC SUPPLIER ACCUM-MATIC SYSTEMS INC SUPPLIER ACCURATE MACHINE AND TOOL CORP SUPPLIER ACCURATE ROLL ENGINEERING CORP SUPPLIER Accurate Technologies Inc SUPPLIER Accuride Corporation SUPPLIER Ace Hardware Corporation FLEET ACE PRODUCTS INC SUPPLIER ACG Direct Inc. -

Download Presentation

Genesee & Wyoming Australia Challenges and Opportunities in the SA rail sector Genesee & Wyoming Inc. February, 20161 Forward-Looking Statements This presentation contains “forward-looking statements” regarding future events and the future performance of Genesee & Wyoming Inc. that involve risks and uncertainties that could cause actual results to differ materially from those expressed or forecasted, including, but not limited to, economic conditions, customer demand, increased competition in the relevant market, the integration of RailAmerica railroads, and others, many of which are beyond our control. The Company refers you to the documents that it files from time to time with the Securities and Exchange Commission, such as the Company’s Forms 10-Q and 10-K, which contain additional important factors that could cause its actual results to differ from its current expectations and from the forward-looking statements discussed during this presentation. Forward-looking statements speak only as of the date of this presentation or the date they were made. Genesee & Wyoming Inc. does not undertake, and expressly disclaims, any duty to update any forward- looking statement contained in this presentation whether as a result of new information, future events or otherwise, except as required by law. Genesee & Wyoming Australia 2 GWA Priorities 1. Safety: Our No. 1 priority 2. Customer Service: We exist to serve our customers 3. Local Accountability: Make decisions closest to the facts 4. Commitment to Excellence: Continuous improvement 5. Long-Term Partnerships: Customers, Large US Railroads, Local Communities 6. Long-Term Decision Making: Stewards of vital infrastructure assets Genesee & Wyoming Australia 3 Our Core Purpose To be the safest and most respected rail service provider in the world. -

KEN MILLER Oklahoma State Treasurer It’S Your Money

A Message From KEN MILLER Oklahoma State Treasurer It’s your money. Please come get it! Please take a few minutes to see if your name is included on this list of all new names to see if you have treasure waiting to be claimed. Oklahoma businesses bring unclaimed cash, rebates, paychecks, royalties, stock and bonds to my office and it’s my job to return the money to the owners and heirs. Our service is always free and there is no time limit on claiming your property! These are just the most recent names we have received. Our online database contains thousands of names dating back to Search and file a claim online for your 1967. If your name is not on this list, check our website at: unclaimed property. Go to: www.treasurer.ok.gov www.treasurer.ok.gov If you find your name, start your claim online or use the form on the back. to get started. For all other questions Thank you, about unclaimed property, call us at 405-521-4273 Ken Miller, Oklahoma State Treasurer NOTICE OF NAMES OF PERSONS APPEARING TO BE OWNERS OF ABANDONED PROPERTY JULY 2011 – Newspaper Advertising Supplement 2 ADAIR COUNTY — BUNCH JULY 2011 • UNCLAIMED PROPERTY BEAVER COUNTY — BEAVER SOAP HAZEL MITCHELL NEILA NOELS OIL ADAIR RT BOX 165 COUNRTY VILL MOBILE PO BOX 387 SWIMMER CHERRIE L HOME PRK B OWEN GEORGIA BUNCH PO BOX 1097 MURRAY ASHLEY 704 W 13TH ST TABLE OF CONTENTS RODNEY KIMBLE TEEHEE CHARLOTTEA RT 1 BOX 556 PLEASANT PARALEE D PO BOX 2 RR 4 BOX 320 PRIETO KAMISHA RR 2 BOX 1170 ADAIR COUNTY PAGE 2 LOVE COUNTY PAGE 28 PROCTOR THIRSTY ASHLEY ANN 209 W CHINCAPIN PREFERRED PHCY RT1 BOX 1529 SAWNEY EDWARD L PROVIDERS OF SE OK ALFALFA COUNTY PAGE 2 MAJOR COUNTY PAGE 28 BAILEY WAYNE MR P.O. -

Financing Good Times

60DegreeTiffin_RIS.qxp 5/4/07 2:11 PM Page 1 =afYf[af_Ü_gg\Ülae]kÜ *GZPVS3FDSFBUJPOBM7FIJDMF 37 IBTBDIBTTJTNBOVGBDUVSFECZ'SFJHIUMJOFS$VTUPN$IBTTJT$PSQ ZPVDBOOPXUBLF TURNING IT UP, AGAIN. BEWBOUBHFPG¾OBODJOHGSPN%BJNMFS$ISZTMFS %$ 5SVDL'JOBODJBMBOE&TTFY$SFEJU5IJTOFXQSPHSBNPGGFSTZPVNBOZ BEWBOUBHFTPWFSUSBEJUJPOBMMFOEFSTJODMVEJOHUIFTUSFOHUIPG%BJNMFS$ISZTMFS DPNQFUJUJWFSBUFTBOEPVSFYQFSJFODFBT Introducing another industry first by Freightliner Custom Chassis. POFPGUIFNPTUSFTQFDUFEDBQUJWF¾OBODFDPNQBOJFTJOUIFXPSME We’ve done it. Freightliner Custom Chassis’ new independent front 8JUIBO37CVJMUPOB'SFJHIUMJOFSDIBTTJT ZPVIBWFBDDFTTUPBXFCTJUFUIBUNBLFTJUTJNQMFUPBQQMZBOEHFUUIF suspension by ZF®, with an industry-leading 60-degree wheel cut, ¾OBODJOHZPVOFFE"UXXXFTTFYDSFEJUDPNGDDD ZPVµMMCFBCMFUPBQQMZGPSBSF¾OBODFPGZPVSFYJTUJOH37MPBO HFU enables you to maneuver like you’ve never thought possible. ¾OBODJOHGPSBOFX37PSFWFOHFUBMPBOGPSBVTFE37 Why? It’s about negotiating those tighter spaces and tighter turns; (PUPXXXFTTFYDSFEJUDPNGDDDBOEVTFUIF¾OBODJOHMJOLUPBDDFTTSBUFRVPUBUJPOTBOEZPVSPOMJOFDSFEJUBQQMJDBUJPO about having more controlled confidence at the wheel; about +PJOUIFNJMMJPOTPGDVTUPNFSTXPSMEXJEFXIPSFMZPO%BJNMFS$ISZTMFSGPSDVTUPNUBJMPSFE¾OBODFTPMVUJPOT expanding the limits of where you go and how you get there. 'JOBODFZPVSHPPEUJNFT So don’t be afraid of the road ahead…take on the world one turn at a time with Freightliner Custom Chassis, The Leader at Every Turn. 1.800.545.8831 | freightlinerchassis.com ESSEX CREDIT Call Freightliner Custom Chassis Corporation -

Draft Service Level NEPA Document- V2

TIER 1 ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT FOR OKLAHOMA DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION NORTHERN SECTION OF THE SOUTH CENTRAL HIGH SPEED INTERCITY PASSENGER RAIL SEPTEMBER 2009 TIER ONE ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT FOR NORTH SECTION OF THE SOUTH CENTRAL HIGH SPEED RAIL CORRIDOR IN OKLAHOMA Located In Oklahoma, Lincoln, Creek and Tulsa Counties, Oklahoma The focus of this document is to provide a Tier 1 Environmental Assessment pursuant to the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). This documentation will focus on broad issues such as purpose and need, general location of alternatives, and avoidance and minimization of potential environmental effects for the North (Oklahoma City/Tulsa) Section for Oklahoma's portion of the South Central High Speed Rail Corridor. Prepared For: Oklahoma Department of Transportation & Federal Railroad Administration Prepared By: Able Consulting 9225 North 133rd East Avenue Owasso, Oklahoma 74055 September 2009 ENVIRONMENTAL CORRIDOR ANALYSIS 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE ...................................................................................................................................................... 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................................... 3 1.0 INTRODUCTION AND LOCATION ...................................................................................................... 5 2.0 PURPOSE AND NEED FOR THE PROJECT ...................................................................................... 8 -

The World's Leading and Only Monthly Magazine for the Dry Bulk Industry

i DRY CARGO DC international ISSUE NO.164 NOVEMBER 2013 FEATURES Fertilizer Trades Cement Handling Handymax Bulkers France & Belgium FIBCs & Bagging Equipment The world’s leading and only monthly magazine for the dry bulk industry VERSTEGEN GRAB MORE MORE GRAB 6ERSTEGEN'RIJPERS"6s0/"OXs"!.IEUWEGEINs4HE.ETHERLANDS TEL sFAX EMAILINFO VERSTEGENNETsWEBSITEWWWVERSTEGENNET CONTENTS VIGAN 600tph pneumatic ship-unloader for transshipment from DCi ocean vessels to river barges in the port of Alexandria, Egypt. VIGAN also delivered to the same NSSC company two pneumatic barge unloaders, each one with a capacity of 250tph and mounted on gantries travelling on rails. VIGAN Engineering S.A. Rue de l’Industrie, 16 BE – 1400 Nivelles Belgium T : + 32 67 89 50 41 F : + 32 67 89 50 60 E : [email protected] W : www.vigan.com PUBLISHERS Jason Chinnock [email protected] NOVEMBER 2013 issue Andrew Hucker-Brown [email protected] EDITORIAL featuring... Louise Dodds-Ely Editor [email protected] Jay Venter Deputy Editor [email protected] TRADE & COMMODITIES Samantha Smith Directories [email protected] Vital support from coal trade 2 Stephanie Hodgkins Office Manager The long and winding road to US coal exports 4 [email protected] Reshuffling the grain trade exporters pack 6 SALES GLOBAL FERTILIZER OUTLOOK 9 Lourens van Emmenis Sales Director [email protected] Matthew Currin Senior Sales Executive [email protected] SHIPPING & TRANSPORT CORRESPONDENTS Twenty MacGregor cranes ordered for multi-purpose vessels 20 Brazil Patrick Knight HANDYMAX BULKERS: -

Annual Report and Audited Financial Statements 2013 RAIL JOURNEYS 2013 of the WORLD

RAIL JOURNEYS 2013 OF THE WORLD Annual Report and Audited Financial Statements 2013 RAIL JOURNEYS 2013 OF THE WORLD The theme for this year’s annual report and accounts is rail journeys of the world. Find out more about each journey at the back of this booklet. Contents Trustee Company’s responsibilities in respect of Statement of contributions Trustee Company The Railways and summary responsibilities Pension of contributions in relation to The Trustee’s Scheme Audited payable in the year audited financial Investment Financial statements Report Appendices Statements 04 07 10 11 20 21 22 23 24 35 38 39 Actuary’s Key Statistics Report Chairman’s Independent The Trustee introduction Auditor’s Company report Independent Annual Report Auditor’s Statement about contributions to the Trustee of the RPS On behalf of your Trustee Board I introduce the Annual Report and Audited Financial Statements of the Railways Pension Scheme (‘the Scheme’) for the year ended 31 December 2013. Investment returns in 2013 were reasonably strong. The Growth (Pooled) Fund, in which well over half the Scheme’s assets are now invested, performed well both in absolute terms (8.6%) and against benchmark (3.5%), propelled by another “double digit” year for the equities in which more than 40% of that fund is invested. The Growth Fund will not, however, match the performance of equities; rather, it is designed to balance out the risks and volatile returns associated with single-asset strategies by investing in a wide range of assets, targeting a long-term return of 5% per annum above UK RPI inflation. -

Eligible Company List - Updated 2/1/2018

Eligible Company List - Updated 2/1/2018 S10009 3 Dimensional Services Rochester Hills, MI Supplier Employees Only S65830 3BL Media LLC North Hampton, MA Supplier Employees Only S69510 3D Systems Rock Hill, SC Supplier Employees Only S65364 3IS Inc Novi, MI Supplier Employees Only S70521 3R Manufacturing Company Goodell, MI Supplier Employees Only S61313 7th Sense LP Bingham Farms, MI Supplier Employees Only D18911 84 Lumber Company Eighty Four, PA DCC Employees Only S42897 A & S Industrial Coating Co Inc Warren, MI Supplier Employees Only S73205 A and D Technology Inc Ann Arbor, MI Supplier Employees Only S57425 A G Manufacturing Harbour Beach, MI Supplier Employees Only S01250 A G Simpson (USA) Inc Sterling Heights, MI Supplier Employees Only F02130 A G Wassenaar Denver, CO Fleet Employees Only S80904 A J Rose Manufacturing Avon, OH Supplier Employees Only S19787 A OK Precision Prototype Inc Warren, MI Supplier Employees Only S62637 A Raymond Tinnerman Automotive Inc Rochester Hills, MI Supplier Employees Only S82162 A Schulman Inc Fairlawn, OH Supplier Employees Only S78336 A T Kearney Inc Chicago, IL Supplier Employees Only D80005 A&E Television Networks New York, NY DCC Employees Only S64720 A.P. Plasman Inc. Fort Payne, AL Supplier Employees Only S36205 AAA National Office (Only EMPLOYEES Eligible) Heathrow, FL Supplier Employees Only S31320 AAF McQuay Inc Louisville, KY Supplier Employees Only S14541 Aarell Process Controls Group Troy, MI Supplier Employees Only F05894 ABB Inc Cary, NC Fleet Employees Only S10035 Abbott Ball Co -

Choosing and Developing a Multi-Modal Transport Solution Guide Acknowledgements

Choosing and Developing a Multi-modal Transport Solution Guide Acknowledgements The Freight Best Practice programme would like to thank the following two organisations for their significant contributions to the case studies in this guide: Rail Freight Group Freight by Water (formerly Sea and Water), now part of FTA The Freight Best Practice programme would also like to thank the following people and organisations for their contributions to the case studies and photographs in this guide: • Alan Woodburn • British Waterways • Frank Worsford • Freight on Rail • Freight Transport Association • Gavin Roser • Mike Browne • Neil Stevens • Network Rail Plc • Port of London • Steve Mulvey The Freight Best Practice programme would like to thank the large number of companies and organisations featured in the case studies. A full list of these can be found in the Contents Page. Front Cover Photograph A Fastline locomotive at the head of a container train at Birmingham Intermodal Freight Terminal, one of the newer freight terminals and featured in Case Study 31. Due to problems with its Parent Group Fastline ceased trading in March 2010. Disclaimer: While the Department for Transport (DfT) has made every effort to ensure the information in this document is accurate, DfT does not guarantee the accuracy, completeness or usefulness of that information; and it cannot accept liability for any loss or damages of any kind resulting from reliance on the information or guidance this document contains. Foreword Freight Best Practice is funded by the Department for Transport and managed by AECOM Ltd to promote operational efficiency within freight operations in England. Freight Best Practice offers FREE essential information for the freight industry, covering topics such as saving fuel, developing skills, equipment and systems, operational efficiency and performance management. -

Appendix 3 Freightliner CSR , Item 22. PDF 547 KB

APPENDIX 3 Corporate Chief Executive statement and summary 02 Who we are and where we operate 03 Environment 06 Social Employee wellbeing and investment 14 Responsibility Community and charities 16 Policy FREIGHTLINER’S cORPORATE SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY 1 APPENDIX 3 Chief Executive Statement And Summary Summary Freightliner Group has an Environmental Policy which is briefed to all staff when they join the company and each employee receives an employee handbook at their induction which explains the key company policies. It is also available on the Internet for the general public. The “ Freightliner is the market leader statement sets out the Freightliner policy and officially the most reliable rail for its commitment to environmental freight operator in the UK. Since protection. 2005 we have expanded operations Freightliner’s core business of moving to Poland and Australia . freight by rail is more environmentally Our success is based on setting new friendly than moving freight by road, standards of customer service in thus we enable our customers to reach terms of reliability, flexibility and their CSR targets and in turn make innovation. them more friendly to the environment. Calculations show that in any average Our continued growth and month Freightliner in the UK replaces expanded activity in all areas of the over 50,000 lorry journeys and saves business only puts more importance thousands of tonnes of CO2, thus on the impact of our operations in contributing on behalf of our customers the environment and on our local to reducing the -

RCRA Notifiers Listing

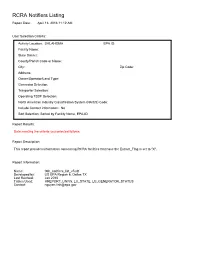

RCRA Notifiers Listing Report Date: April 13, 2018 11:12 AM User Selection Criteria: Activity Location: OKLAHOMA EPA ID: Facility Name: State District: County/Parish Code or Name: City: Zip Code: Address: Owner/Operator/Land Type: Generator Selection: Tranporter Selection: Operating TSDF Selection: North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) Code: Include Contact information: No Sort Selection: Sorted by Facility Name, EPA-ID Report Results: Data meeting the criteria you selected follows. Report Description: This report provides information concerning RCRA facilities that have the Extract_Flag is set to "X". Report Information: Name: 06h_notifiers_list_v5.rdf Developed by: US EPA Region 6, Dallas TX Last Revised: Jan 2010 Tables Used: HREPORT_UNIV5, LU_STATE, LU_GENERATOR_STATUS Contact: [email protected] Report run on: April 13, 2018 11:12 AM RCRA NOTIFIERS LISTING Page: 1 Report Title: 06h_notifiers_list_v5.rdf Source: USEPA RCRAInfo Database State of: OKLAHOMA S T L G G R O O A COUNTY/ E E A OPER W P N RECEIVED EPA-ID FACILITY NAME LOCATION ADDRESS CITY ZIP PARISH N N N TSDF N R D DATE OKD028596435 1 HOUR CLEANERS INC 556 N DENVER TULSA 74103 TULSA 3 ----- P 11/13/85 OKD033141334 15TH STREET BODY SHOP 6929 E 15TH ST TULSA 74112 TULSA 3 ----- P 02/13/89 OKR000004044 21ST CENTURY AUTOMOTIVE 5700 TINKER DIAGONAL MIDWEST CITY 73110 OKLAHOMA ----- P P 01/26/06 OKR000018028 21ST CENTURY AUTOMOTIVE 201 W RENO AVE OKLAHOMA CITY 73127 OKLAHOMA ----- P P 10/16/02 OKR000018036 21ST CENTURY AUTOMOTIVE 509 E MEMORIAL RD OKLAHOMA CITY