Inferential Evidentiality and Mirativity in Caquinte

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Animacy and Alienability: a Reconsideration of English

Running head: ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 1 Animacy and Alienability A Reconsideration of English Possession Jaimee Jones A Senior Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation in the Honors Program Liberty University Spring 2016 ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 2 Acceptance of Senior Honors Thesis This Senior Honors Thesis is accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation from the Honors Program of Liberty University. ______________________________ Jaeshil Kim, Ph.D. Thesis Chair ______________________________ Paul Müller, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Jeffrey Ritchey, Ph.D. Committee Member ______________________________ Brenda Ayres, Ph.D. Honors Director ______________________________ Date ANIMACY AND ALIENABILITY 3 Abstract Current scholarship on English possessive constructions, the s-genitive and the of- construction, largely ignores the possessive relationships inherent in certain English compound nouns. Scholars agree that, in general, an animate possessor predicts the s- genitive while an inanimate possessor predicts the of-construction. However, the current literature rarely discusses noun compounds, such as the table leg, which also express possessive relationships. However, pragmatically and syntactically, a compound cannot be considered as a true possessive construction. Thus, this paper will examine why some compounds still display possessive semantics epiphenomenally. The noun compounds that imply possession seem to exhibit relationships prototypical of inalienable possession such as body part, part whole, and spatial relationships. Additionally, the juxtaposition of the possessor and possessum in the compound construction is reminiscent of inalienable possession in other languages. Therefore, this paper proposes that inalienability, a phenomenon not thought to be relevant in English, actually imbues noun compounds whose components exhibit an inalienable relationship with possessive semantics. -

Veridicality and Utterance Meaning

2011 Fifth IEEE International Conference on Semantic Computing Veridicality and utterance understanding Marie-Catherine de Marneffe, Christopher D. Manning and Christopher Potts Linguistics Department Stanford University Stanford, CA 94305 {mcdm,manning,cgpotts}@stanford.edu Abstract—Natural language understanding depends heavily on making the requisite inferences. The inherent uncertainty of assessing veridicality – whether the speaker intends to convey that pragmatic inference suggests to us that veridicality judgments events mentioned are actual, non-actual, or uncertain. However, are not always categorical, and thus are better modeled as this property is little used in relation and event extraction systems, and the work that has been done has generally assumed distributions. We therefore treat veridicality as a distribution- that it can be captured by lexical semantic properties. Here, prediction task. We trained a maximum entropy classifier on we show that context and world knowledge play a significant our annotations to assign event veridicality distributions. Our role in shaping veridicality. We extend the FactBank corpus, features include not only lexical items like hedges, modals, which contains semantically driven veridicality annotations, with and negations, but also structural features and approximations pragmatically informed ones. Our annotations are more complex than the lexical assumption predicts but systematic enough to of world knowledge. The resulting model yields insights into be included in computational work on textual understanding. the complex pragmatic factors that shape readers’ veridicality They also indicate that veridicality judgments are not always judgments. categorical, and should therefore be modeled as distributions. We build a classifier to automatically assign event veridicality II. CORPUS ANNOTATION distributions based on our new annotations. -

The Term Declension, the Three Basic Qualities of Latin Nouns, That

Chapter 2: First Declension Chapter 2 covers the following: the term declension, the three basic qualities of Latin nouns, that is, case, number and gender, basic sentence structure, subject, verb, direct object and so on, the six cases of Latin nouns and the uses of those cases, the formation of the different cases in Latin, and the way adjectives agree with nouns. At the end of this lesson we’ll review the vocabulary you should memorize in this chapter. Declension. As with conjugation, the term declension has two meanings in Latin. It means, first, the process of joining a case ending onto a noun base. Second, it is a term used to refer to one of the five categories of nouns distinguished by the sound ending the noun base: /a/, /ŏ/ or /ŭ/, a consonant or /ĭ/, /ū/, /ē/. First, let’s look at the three basic characteristics of every Latin noun: case, number and gender. All Latin nouns and adjectives have these three grammatical qualities. First, case: how the noun functions in a sentence, that is, is it the subject, the direct object, the object of a preposition or any of many other uses? Second, number: singular or plural. And third, gender: masculine, feminine or neuter. Every noun in Latin will have one case, one number and one gender, and only one of each of these qualities. In other words, a noun in a sentence cannot be both singular and plural, or masculine and feminine. Whenever asked ─ and I will ask ─ you should be able to give the correct answer for all three qualities. -

Chapter 6 Mirativity and the Bulgarian Evidential System Elena Karagjosova Freie Universität Berlin

Chapter 6 Mirativity and the Bulgarian evidential system Elena Karagjosova Freie Universität Berlin This paper provides an account of the Bulgarian admirative construction andits place within the Bulgarian evidential system based on (i) new observations on the morphological, temporal, and evidential properties of the admirative, (ii) a criti- cal reexamination of existing approaches to the Bulgarian evidential system, and (iii) insights from a similar mirative construction in Spanish. I argue in particular that admirative sentences are assertions based on evidence of some sort (reporta- tive, inferential, or direct) which are contrasted against the set of beliefs held by the speaker up to the point of receiving the evidence; the speaker’s past beliefs entail a proposition that clashes with the assertion, triggering belief revision and resulting in a sense of surprise. I suggest an analysis of the admirative in terms of a mirative operator that captures the evidential, temporal, aspectual, and modal properties of the construction in a compositional fashion. The analysis suggests that although mirativity and evidentiality can be seen as separate semantic cate- gories, the Bulgarian admirative represents a cross-linguistically relevant case of a mirative extension of evidential verbal forms. Keywords: mirativity, evidentiality, fake past 1 Introduction The Bulgarian evidential system is an ongoing topic of discussion both withre- spect to its interpretation and its morphological buildup. In this paper, I focus on the currently poorly understood admirative construction. The analysis I present is based on largely unacknowledged observations and data involving the mor- phological structure, the syntactic environment, and the evidential meaning of the admirative. Elena Karagjosova. -

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: a Case Study from Koro

Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro By Jessica Cleary-Kemp A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair Assistant Professor Peter S. Jenks Professor William F. Hanks Summer 2015 © Copyright by Jessica Cleary-Kemp All Rights Reserved Abstract Serial Verb Constructions Revisited: A Case Study from Koro by Jessica Cleary-Kemp Doctor of Philosophy in Linguistics University of California, Berkeley Associate Professor Lev D. Michael, Chair In this dissertation a methodology for identifying and analyzing serial verb constructions (SVCs) is developed, and its application is exemplified through an analysis of SVCs in Koro, an Oceanic language of Papua New Guinea. SVCs involve two main verbs that form a single predicate and share at least one of their arguments. In addition, they have shared values for tense, aspect, and mood, and they denote a single event. The unique syntactic and semantic properties of SVCs present a number of theoretical challenges, and thus they have invited great interest from syntacticians and typologists alike. But characterizing the nature of SVCs and making generalizations about the typology of serializing languages has proven difficult. There is still debate about both the surface properties of SVCs and their underlying syntactic structure. The current work addresses some of these issues by approaching serialization from two angles: the typological and the language-specific. On the typological front, it refines the definition of ‘SVC’ and develops a principled set of cross-linguistically applicable diagnostics. -

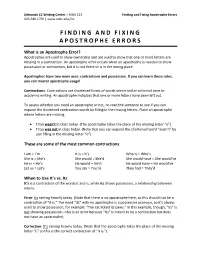

Finding and Fixing Apostrophe Errors 425.640.1750 |

Edmonds CC Writing Center | MUK 113 Finding and Fixing Apostrophe Errors 425.640.1750 | www.edcc.edu/lsc FINDING AND FIXING APOSTROPHE ERRORS What is an Apostrophe Error? Apostrophes are used to show ownership and are used to show that one or more letters are missing in a contraction. An apostrophe error occurs when an apostrophe is needed to show possession or contraction, but it is not there or is in the wrong place. Apostrophes have two main uses: contractions and possession. If you can learn these rules, you can master apostrophe usage! Contractions: Contractions are shortened forms of words which add an informal tone to academic writing. An apostrophe indicates that one or more letters have been left out. To assess whether you need an apostrophe or not, re-read the sentence to see if you can expand the shortened contraction words by filling in the missing letters. Place an apostrophe where letters are missing. Thao wasn’t in class today. (The apostrophe takes the place of the missing letter “o”). Thao was not in class today. (Note that you can expand the shortened word “wasn’t” by just filling in the missing letter “o”). These are some of the most common contractions: I am = I’m It is = It’s Who is = Who’s She is = She’s She would = She’d She would have = She would’ve He is = He’s He would = He’d He would have = He would’ve Let us = Let’s You are = You’re They had = They’d When to Use It’s vs. -

A Syntactic Analysis of Rhetorical Questions

A Syntactic Analysis of Rhetorical Questions Asier Alcázar 1. Introduction* A rhetorical question (RQ: 1b) is viewed as a pragmatic reading of a genuine question (GQ: 1a). (1) a. Who helped John? [Mary, Peter, his mother, his brother, a neighbor, the police…] b. Who helped John? [Speaker follows up: “Well, me, of course…who else?”] Rohde (2006) and Caponigro & Sprouse (2007) view RQs as interrogatives biased in their answer set (1a = unbiased interrogative; 1b = biased interrogative). In unbiased interrogatives, the probability distribution of the answers is even.1 The answer in RQs is biased because it belongs in the Common Ground (CG, Stalnaker 1978), a set of mutual or common beliefs shared by speaker and addressee. The difference between RQs and GQs is thus pragmatic. Let us refer to these approaches as Option A. Sadock (1971, 1974) and Han (2002), by contrast, analyze RQs as no longer interrogative, but rather as assertions of opposite polarity (2a = 2b). Accordingly, RQs are not defined in terms of the properties of their answer set. The CG is not invoked. Let us call these analyses Option B. (2) a. Speaker says: “I did not lie.” b. Speaker says: “Did I lie?” [Speaker follows up: “No! I didn’t!”] For Han (2002: 222) RQs point to a pragmatic interface: “The representation at this level is not LF, which is the output of syntax, but more abstract than that. It is the output of further post-LF derivation via interaction with at least a sub part of the interpretational component, namely pragmatics.” RQs are not seen as syntactic objects, but rather as a post-syntactic interface phenomenon. -

Tagalog Pala: an Unsurprising Case of Mirativity

Tagalog pala: an unsurprising case of mirativity Scott AnderBois Brown University Similar to many descriptions of miratives cross-linguistically, Schachter & Otanes(1972)’s clas- sic descriptive grammar of Tagalog describes the second position particle pala as “expressing mild surprise at new information, or an unexpected event or situation.” Drawing on recent work on mi- rativity in other languages, however, we show that this characterization needs to be refined in two ways. First, we show that while pala can be used in cases of surprise, pala itself merely encodes the speaker’s sudden revelation with the counterexpectational nature of surprise arising pragmatically or from other aspects of the sentence such as other particles and focus. Second, we present data from imperatives and interrogatives, arguing that this revelation need not concern ‘information’ per se, but rather the illocutionay update the sentence encodes. Finally, we explore the interactions between pala and other elements which express mirativity in some way and/or interact with the mirativity pala expresses. 1. Introduction Like many languages of the Philippines, Tagalog has a prominent set of discourse particles which express a variety of different evidential, attitudinal, illocutionary, and discourse-related meanings. Morphosyntactically, these particles have long been known to be second-position clitics, with a number of authors having explored fine-grained details of their distribution, rela- tive order, and the interaction of this with different types of sentences (e.g. Schachter & Otanes (1972), Billings & Konopasky(2003) Anderson(2005), Billings(2005) Kaufman(2010)). With a few recent exceptions, however, comparatively little has been said about the semantics/prag- matics of these different elements beyond Schachter & Otanes(1972)’s pioneering work (which is quite detailed given their broad scope of their work). -

Workshop Proposal: Associated Motion in African Languages WOCAL 2021, Universiteit Leiden Organizers: Roland Kießling (Universi

Workshop proposal: Associated motion in African languages WOCAL 2021, Universiteit Leiden Organizers: Roland Kießling (University of Hamburg) Bastian Persohn (University of Hamburg) Daniel Ross (University of Illinois, UC Riverside) The grammatical category of associated motion (AM) is constituted by markers related to the verb that encode translational motion (e.g. Koch 1984; Guillaume 2016). (1–3) illustrate AM markers in African languages. (1) Kaonde (Bantu, Zambia; Wright 2007: 32) W-a-ká-leta buta. SUBJ3SG-PST-go_and-bring gun ʻHe went and brought the gun.ʻ (2) Wolof (Atlantic, Senegal and Gambia; Diouf 2003, cited by Voisin, in print) Dafa jàq moo tax mu seet-si la FOC.SUBJ3SG be_worried FOC.SUBJ3SG cause SUBJ3SG visit-come_and OBJ2SG ‘He's worried, that's why he came to see you.‘ (3) Datooga (Nilotic, Tanzania; Kießling, field notes) hàbíyóojìga gwá-jòon-ɛ̀ɛn ʃɛ́ɛróodá bàɲêega hyenas SUBJ3SG-sniff-while_coming smell.ASS meat ‘The hyenas come sniffing (after us) because of the meat’s smell.’ Associated motion markers are a common device in African languages, as evidenced in Belkadi’s (2016) ground-laying work, in Ross’s (in press) global sample as well as by the available surveys of Atlantic (Voisin, in press), Bantu (Guérois et al., in press), and Nilotic (Payne, in press). In descriptive works, AM markers are often referred to by other labels, such as movement grams, distal aspects, directional markers, or itive/ventive markers. Typologically, AM systems may vary with respect to the following parameters (e.g. Guillaume 2016): Complexity: How many dedicated AM markers do actually contrast? Moving argument:: Which is the moving entity (S/A vs. -

Chapter 1 Negation in a Cross-Linguistic Perspective

Chapter 1 Negation in a cross-linguistic perspective 0. Chapter summary This chapter introduces the empirical scope of our study on the expression and interpretation of negation in natural language. We start with some background notions on negation in logic and language, and continue with a discussion of more linguistic issues concerning negation at the syntax-semantics interface. We zoom in on cross- linguistic variation, both in a synchronic perspective (typology) and in a diachronic perspective (language change). Besides expressions of propositional negation, this book analyzes the form and interpretation of indefinites in the scope of negation. This raises the issue of negative polarity and its relation to negative concord. We present the main facts, criteria, and proposals developed in the literature on this topic. The chapter closes with an overview of the book. We use Optimality Theory to account for the syntax and semantics of negation in a cross-linguistic perspective. This theoretical framework is introduced in Chapter 2. 1 Negation in logic and language The main aim of this book is to provide an account of the patterns of negation we find in natural language. The expression and interpretation of negation in natural language has long fascinated philosophers, logicians, and linguists. Horn’s (1989) Natural history of negation opens with the following statement: “All human systems of communication contain a representation of negation. No animal communication system includes negative utterances, and consequently, none possesses a means for assigning truth value, for lying, for irony, or for coping with false or contradictory statements.” A bit further on the first page, Horn states: “Despite the simplicity of the one-place connective of propositional logic ( ¬p is true if and only if p is not true) and of the laws of inference in which it participate (e.g. -

Evidentiality

Evidentiality This section covers evidentiality, mirativity, and validational force, as separate concepts that are closely intertwined. Evidentiality in Balti is expressed with clause-final particles, and are generally uninflected for tense or aspect. There is a distinction between the sources of evidence for a statement, and a multi-tiered distinction in validational force. 1 Hearsay In Balti, information that the speaker has experienced first-hand, or has any kind of first- hand knowledge of, is unmarked. In the first example below, the speaker has absolute knowledge that it’s raining, from experiencing it himself; perhaps he is outside and feels the rain hitting his skin, or sees it from a window. (1) namkor oŋ-en jʊt rain come-PROG COP ‘It’s raining.’ (first-hand knowledge) If the speaker gained this knowledge from another person, without witnessing the event himself, he expresses this source of information with the hearsay particle ‘lo’, which always occurs clause-finally. (2) namkor oŋ-en jʊt lo Rain come-PROG COP HSY ‘It’s raining.’ (hearsay) This particle occurs when the speaker is telling someone else, other than the person he received the information from. In other words, if I told Muhammad that it’s raining, and he went to tell someone else that it’s raining, he would express it using example 2 above. In this scenario, Muhammad had been in a basement all day with no windows and thus didn’t perceive any evidence of rain, and I had first-hand knowledge that it’s raining. This particle is uninflected for tense/aspect, and can be used with any tense. -

Like, Hedging and Mirativity. a Unified Account

Like, hedging and mirativity. A unified account. Abstract (4) Never thought I would say this, but Lil’ Wayne, is like. smart. We draw a connection between ‘hedging’ (5) My friend I used to hang out with is like use of the discourse particle like in Amer- . rich now. ican English and its use as a mirative marker of surprise. We propose that both (6) Whoa! I like . totally won again! uses of like widen the size of a pragmati- cally restricted set – a pragmatic halo vs. a In (4), the speaker is signaling that they did not doxastic state. We thus derive hedging and expect to discover that Lil Wayne is smart; in (5) surprise effects in a unified way, outlining the speaker is surprised to learn that their former an underlying link between the semantics friend is now rich; and in (6) the speaker is sur- of like and the one of other mirative mark- prised by the fact that they won again. ers cross-linguistically. After presenting several diagnostics that point to a genuine empirical difference between these 1 Introduction uses, we argue that they do in fact share a core grammatical function: both trigger the expansion Mirative expressions, which mark surprising in- of a pragmatically restricted set: the pragmatic formation (DeLancey 1997), are often expressed halo of an expression for the hedging variant; and through linguistic markers that are also used to en- the doxastic state of the speaker for the mirative code other, seemingly unrelated meanings – e.g., use. We derive hedging and mirativity as effects evidential markers that mark lack of direct evi- of the particular type of object to which like ap- dence (Turkish: Slobin and Aksu 1982; Peterson plies.