The Curriculum and Community Enterprise for Restoration Science Partnership Model

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

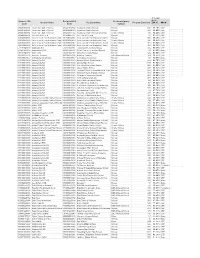

CEP May 1 Notification for USDA

40% and Sponsor LEA Recipient LEA Recipient Agency above Sponsor Name Recipient Name Program Enroll Cnt ISP % PROV Code Code Subtype 280201860934 Academy Charter School 280201860934 Academy Charter School School 435 61.15% CEP 280201860934 Academy Charter School 800000084303 Academy Charter School School 605 61.65% CEP 280201860934 Academy Charter School 280202861142 Academy Charter School-Uniondale Charter School 180 72.22% CEP 331400225751 Ach Tov V'Chesed 331400225751 Ach Tov V'Chesed School 91 90.11% CEP 333200860906 Achievement First Bushwick Charte 331300860902 Achievement First Endeavor Charter School 805 54.16% CEP 333200860906 Achievement First Bushwick Charte 800000086469 Achievement First University Prep Charter School 380 54.21% CEP 333200860906 Achievement First Bushwick Charte 332300860912 Achievement First Brownsville Charte Charter School 801 60.92% CEP 333200860906 Achievement First Bushwick Charte 333200860906 Achievement First Bushwick Charter School 393 62.34% CEP 570101040000 Addison CSD 570101040001 Tuscarora Elementary School School 455 46.37% CEP 410401060000 Adirondack CSD 410401060002 West Leyden Elementary School School 139 40.29% None 080101040000 Afton CSD 080101040002 Afton Elementary School School 545 41.65% CEP 332100227202 Ahi Ezer Yeshiva 332100227202 Ahi Ezer Yeshiva BJE Affiliated School 169 71.01% CEP 331500629812 Al Madrasa Al Islamiya 331500629812 Al Madrasa Al Islamiya School 140 68.57% None 010100010000 Albany City SD 010100010023 Albany School Of Humanities School 554 46.75% CEP 010100010000 Albany -

Knowledge City

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARCHITECTURE, PLANNING, AND PRESERVATION ADV ANCED STUDIO IV ENVIRONMENT Studio Brief Revised 01/19/17 SPRING 2017 NAHYUN HWANG STUDIO KNOWLEDGE CITY Knowledge and the City In 1966, through an unsolicited proposal of “Potteries Thin kbelt,” Cedric Price envisioned a transformation of a townregion of North Staffordshire in England , in which its functional territory was no longer defined by medieval town centers, an ideal grid, or other familiar administrative edifices. Instead, his plan appropriated the existing infrastructural network to produce a new framework for the city education. Although unrealized, the project remains an important moment when knowledge production and its spatial mechanisms were proposed as the main drivers for the definition and transformation of the city. The new relationship between the ideals of the city (education) and the operations of the city (infrastructure, mobility, industry, technology, housing etc.), between the aspirations of the city and its environment, were articulated through the cityscale framework of “anticipatory architecture”1 and the participation of the newly defined student body, the new citizens. Education was a “generator of urban location and form.”2 Participating in the continuing discourse on the relationship between the architecture of education and the city, and acknowledging both precarity3 and possibilities in knowledge in the context of a knowledge economy, this 2017 Spring studio, working with the expanded school program shared yearwide and as a part of the ongoing research and studio series “Knowledge City,” focuses on the typological investigations of experimental educational institutions and their less institutional counterparts. Exploring the possibilities of a novel architecture for knowledge production, exchange, and consumption, the investigation aims to challenge their familiar spatial and institutional formats, while utilizing the potentials in the typology of schools to generate new configurations for collectivity in the city. -

2004 & 2005 Report of Activities

COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY IN THE CITY OF NEW YORK SUMMER RESEARCH PROGRAM FOR SECONDARY SCHOOL SCIENCE TEACHERS 2004 REPORT OF ACTIVITIES 2005 THE PROGRAM ADVISORY COMMITTEE Samuel C. Silverstein, M.D. John C. Dalton Professor Department of Physiology and Cellular Biophysics Program Director O. Roger Anderson, Ph.D. Senior Research Scientist, Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory Professor, Natural Sciences, Teachers College Roy Arezzo, M.S. Teacher Participant, 1996–97 Justine Herrera, B.A. Assistant Director of Education Outreach MRSEC + NSEC Jay Dubner, M.S. Program Coordinator Greg Freyer, Ph.D. Associate Professor of Environmental Health Sciences Denice Gamper, M.S. Teacher Participant, 1992–93 Reba Goodman, Ph.D. Professor Emerita of Pathology Howard Lieberman, Ph.D. Professor of Radiation Oncology John Loike, Ph.D. Research Scientist, Department of Physiology and Cellular Biophysics Amy Mac Dermott, Ph.D. Professor of Physiology and Cellular Biophysics Irene Matejko, Ph.D. Teacher Participant, 1990–91 Christian Meyer, Ph.D. Professor of Civil Engineering Carl Raab, M.S. New York City Department of Education, ret. Britt Reichborn-Kjennerud, B.A. Teacher Participant, 1997–98 Cover printed on recycled paper Summer Research Program for Science Teachers 2004 & 2005 Report of Activities Samuel C. Silverstein, M.D. - Program Director Jay Dubner, M.S. - Program Coordinator www.ScienceTeacherProgram.org Table of Contents Summary and Program Description. 4 Program Effects and Governance. 5 The Program............................................ 6 Program Website........................................ 1 1 Partnerships in Science Education. 1 3 Evaluation. ............................................ 1 8 Operating Costs......................................... 2 1 Acknowledgments. 22 References. 23 Appendices I. Class of 2004.............................................. i II. Class of 2005............................................. iii III. Class of 2006 . -

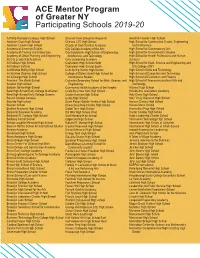

ACE Mentor Program of Greater NY Participating Schools 2019-20

ACE Mentor Program of Greater NY Participating Schools 2019-20 A.Phillip Randolph Campus High School Channel View School for Research Hendrick Hudson High School Abraham Clark High School Chelsea CTE High School High School for Construction Trades, Engineering, Abraham Lincoln High School Church of God Christian Academy and Architecture Academy of American Studies City College Academy of the Arts High School for Contemporary Arts Academy of Finance and Enterprises City Polytechnic High School of Engineering, High School for Environmental Studies Academy of Urban Planning and Engineering Architecture, and Technology High School for Health Professions and Human All City Leadership Academy Civic Leadership Academy Services All Hallows High School Clarkstown High School North High School for Math, Science and Engineering and All Hallows Institute Clarkstown High School South City College of NY Archbishop Molloy High School Cold Spring Harbor High School High School of Arts and Technology Archbishop Stepinac High School College of Staten Island High School for High School of Computers and Technology Art & Design High School International Studies High School of Economics and Finance Avenues: The World School Columbia Secondary School for Math, Science, and High School of Telecommunications Arts and Aviation High School Engineering Technology Baldwin Senior High School Community Health Academy of the Heights Hillcrest High School Bard High School Early College Manhattan Cristo Rey New York High School Hillside Arts and Letters Academy Bard High School Early College Queens Croton Harmon High School Holy Cross High School Baruch College Campus Curtis High School Holy Trinity Diocesan High School Bayside High school Davis Renov Stahler Yeshiva High School Horace Greeley High School Beacon School Democracy Prep Charter High School Horace Mann School Bedford Academy High School Digital Tech High School Humanities Prep High School Benjamin Banneker Academy Dix Hills High School West Hunter College High School Benjamin N. -

Enrollment Report Fall 2018

Enrollment Report Fall 2018 Office of Institutional Research Fall 2018 Enrollment Report Table of Contents Key Findings 3 Fall 2018 College Enrollment Summary 4 Graduate Student Profile 5 Fall 2018 Graduate Student Enrollment Summary 6 Applied, Accepted & Enrolled for Fall 2018, First‐Time Graduate Students 7 Graduate Applicants and Enrolled Student’s Most Recent Prior College 8 Graduate Enrollment at SUNY Campuses 9 Undergraduate Student Profile 10 Fall 2018 Undergraduate Enrollment Summary 11 Student Body by Gender, Permanent Residence and Age 2009‐2018 12 County of Permanent Residence 13 Distribution of Student Enrollment by Ethnicity Fall 2014‐2018 14 Applied, Accepted & Enrolled for Fall 2016 to Fall 2018, First‐Time Students 15 Applied, Accepted & Enrolled for Fall 2016 to Fall 2018, Transfer Students 16 Applied, Accepted & Enrolled for Fall 2016 to Fall 2018, Transfer & First‐Time Combined 17 Undergraduate Enrollment at SUNY Campuses 18 Enrollment by Student Type and Primary Major 19 Enrollment by Curriculum 2009 to 2018 20 New Transfer Students by Curriculum Fall 2014 to Fall 2018 21 New Freshmen Selectivity 22 Top 50 Feeder High Schools by Number of Students Registered 23 Top 50 Feeder High Schools by Number of Students Accepted 24 Alphabetical Listing of Feeder High Schools 25 Most Recent Prior Colleges of Transfer Applicants Sorted by Number Registered 48 New Transfer Students Most Recent Prior College 55 Fall 2018 Enrollment Report Key Findings Graduate Students In only its second year, enrollment in the Master of Science in Technology Management program has more than doubled from 22 to 54 students in Fall 2018. Approximately one‐third of the new enrollees for Fall 2018 are Farmingdale State College alumni. -

Download This PDF File

Journal of Education and Development; Vol. 5, No. 2; August, 2021 ISSN 2529-7996 E-ISSN 2591-7250 Published by July Press Green Job Opportunities Through the Curriculum and Community Enterprise for Restoration Science in New York City Lauren Birney1 & Denise M. McNamara2 1 Pace University, USA 2 The College of Staten Island, USA Correspondence: Lauren Birney, School of Education, Pace University, USA. Tel: 1-212-346-1889x11889. E-mail: [email protected] Received: July 19, 2021 Accepted: August 9, 2021 Online Published: August 10, 2021 doi:10.20849/jed.v5i2.920 URL: https://doi.org/10.20849/jed.v5i2.920 Abstract This paper examines the current understanding of the green economy movement and the critical role that education plays in attracting a viable workforce for this relatively new crusade. By connecting youth with the importance of environmental concerns in their community, tangible opportunities for sustainable change are created. By giving human agency to some of the most marginalized populations in New York City, the opportunity to experience environmental challenges in the community in which they live exposes these students to a plethora of enriching and rewarding employment opportunities. By combining the stewardship of their environment with formal and informal education, the Curriculum and Community Enterprise for Restoration Science in New York City is presenting multiple pathways for employment and educational opportunities in the green economy. Keywords: green economy, sustainability, environmental restoration, oyster restoration 1. Introduction – 21st Century Skills and Unknown Employment Opportunities of the Future As the end of 1999 rapidly approached, two global concerns were brewing. One predicted Y2K technology failure causing internet failure. -

Award Winner Award Winner

AwardAward Volume XVIII, No. 2 • New York City • NOV/DEC 2012 www.EDUCATIONUPDATE.com Winner CUTTING EDGE NEWS FOR ALL THE PEOPLE UPDATE THE EDUCATION THE PAID U.S. POSTAGE U.S. PRESORTED STANDARD PRESORTED 2 EDUCATION UPDATE ■ FPOR ARENTS, Educators & Students ■ NOV/DEC 2012 GUEST EDITORIAL EDUCATION UPDATE MAILING ADDRESS: Achieving Student Success in Community Colleges 695 Park Avenue, Ste. E1509, NY, NY 10065 Email: [email protected] www.EducationUpdate.com By JAY HERSHENSON Programs (ASAP) and 25 students. Tel: 212-650-3552 Fax: 212-410-0591 n today’s highly competitive global the New Community Students in the first cohort were required to PUBLISHERS: economy, community college stu- College at CUNY. overcome any developmental needs in the sum- Pola Rosen, Ed.D., Adam Sugerman, M.A. dents must earn valued degrees We all know how mer before admission, and about a third did so. ADVISORY COUNCIL: as quickly and assuredly as possi- few urban community So when they were ready to start credit-bearing Mary Brabeck, Dean, NYU Steinhardt School of Culture, Ed., and Human Dev.; Christine Cea, ble. Through academic advisement and finan- college students earn courses, they were all up to speed. Ph.D., NYS Board of Regents; Shelia Evans- cial aid support, block class and summer bridge a degree within three There was regular contact with faculty and Tranumn, Chair, Board of Trustees, Casey Family programs, and greater emphasis on study skills, years — in some parts advisors. Students who needed jobs, job skills Programs Foundation; Charlotte K. Frank, we can better assist incoming freshmen to of the country 16 per- and career planning were helped. -

Grant Recipients

NEW YORK CITY GRANT RECIPIENTS 2009 This summer, 89 New York City teachers representing 52 schools close their classroom doors and embark on life- and career-changing odysseys around the world which they designed to fuel personal and professional growth. Empowered by a Fund for Teachers fellowship, these teachers will return to classrooms inspired and energized to share their experiences with students, colleagues and parents. ACADEMY FOR ENVIRONMENTAL LEADERSHIP Mara Cohen BRONX HIGH SCHOOL FOR THE Barbara Vitanza Travel to Indonesia to study human interaction VISUAL ARTS Canvass England, Spain, and Berlin to with marine ecosystems through the AWARE Rowena Adalla explore the historical and cultural connections reef conservation course and a National Establish ties with UNESCO’s Art Education between ancient Earth Art and contemporary Geographic diver course while volunteering Observatories in Hong Kong to enhance Street Art with various conservation projects school’s Living Environment (science) curriculum ACADEMY FOR LANGUAGE & TECHNOLOGY AMISTAD DUAL LANGUAGE SCHOOL PS/IS 311 Russell Wasden Sarah Hesson Peter Maiwald Personally research and explore the harmony, Research Japan’s contemporary arts to Travel to the Philippines to study its checkered history, and literary traditions of ancient Japan explore the balance of tradition and modernity history -- the Spanish American War, the as depicted in the 1000-year-old masterpiece, in Japanese culture effects of WWII, the Marcos Era and the The Tale of Genji Philippine Revolution of 1986 -

MSC High School Placements

MSC High School Placements - 7 Year Summary (Includes Class of 2017) Specialized High Schools (SHSAT-based) High School of American Studies at Lehman College and Audition-or Portfolio-based Schools High School of Math, Science and Engineering at City College Art and Design High School High School for Violin and Dance Art Performance School LaGuardia High School (Programs: Dance, Drama, Bronx Science Instrumental, Tech/Theater, Vocals/Music) Bronx Theater High School Professional Performing Arts School (PPAS) Brooklyn Latin Repertory Company High School for Theatre Arts Brooklyn Tech Special Music School Choir Academy Talent Unlimited: Drama/Instrumental/Theater Arts Frank Sinatra School of the Arts Stuyvesant High School --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- General Academic High Schools International High School at Union Square Academy of Social Action Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis High School Academy for Software Engineering John F. Kennedy High School Archbishop Stepinac High School Lab School for Collaborative Studies (Lab) Bard High School Landmark High School Baruch College Campus High School LaSalle Academy Beacon High School Leadership and Public Service High School Beekman School Lehman Manhattan Prepatory School Bishop Loughlin High School Life Sciences Secondary School Brandeis High School Lindenhurst Senior High School (Long Island) Bronx Design and Construction Academy Manhattan Business Academy Broome Street -

Billion Oyster Project: Linking Public School Teaching and Learning To

Billion Oyster Project: Linking Public School Teaching and Learning to the Ecological Restoration of New York Harbor Using Innovative Applications of Environmental and Digital Technologies Samuel P. Janis, Lauren B. Birney, Robert Newton Billion Oyster Project: Linking Public School Teaching and Learning to the Ecological Restoration of New York Harbor Using Innovative Applications of Environmental and Digital Technologies Samuel P. Janis, Lauren B. Birney, Robert Newton Professor Samuel P. Janis, Restoration Program Director, The New York Harbor Foundation, [email protected] Dr. Lauren B. Birney, Assistant Professor School of Education, Pace University, [email protected] Dr. Robert Newton, Research Scientist, Lamont Doherty Earth Observatory Columbia University, [email protected] Abstract Research consistently shows that children who have opportunities to actively investigate natural settings and engage in problem-based learning greatly benefit from the experiences. They gain skills, interests, knowledge, aspirations, and motivation to learn more. But how can we provide these rich opportunities in densely populated urban areas where resources and access to natural areas are limited? This project will develop and test a model of curriculum and community enterprise to address that issue within the nation's largest urban school system. Middle school students will study New York harbor and the extensive watershed that empties into it, and they will conduct field research in support of restoring native oyster habitats. The project builds on the existing Billion Oyster Project, and will be implemented by a broad partnership of institutions and community resources, including Pace University, the New York City Department of Education, the Columbia University Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, the New York Academy of Sciences, the New York Harbor Foundation, the New York Aquarium, and others. -

2020 Nyc 2020 High School Admissions

2020 NYC HIGH SCHOOL ADMISSIONS GUIDE 2020 NYC HIGH SCHOOL ADMISSIONS GUIDE MySchools.nyc Explore. Choose. Apply. Visit MySchools ( MySchools.nyc) to explore your high school options from your computer or phone, choose programs for your personalized application, and apply—all in one place. Year-round, you can use MySchools to: 0 Search an interactive high school directory for programs by name, location, accessibility, interest areas, academic off erings, activities, sports, and more! 0 Explore programs across the city. During the high school application period, you can also use MySchools to: 0 Access your personalized high school application—your school counselor will tell you how. 0 Save your favorite schools and programs. 0 Schedule your specialized high schools admissions test (SHSAT) or LaGuardia High School audition by early October. 0 Add 12 programs to your high school application. Place them in your order of preference, with your fi rst choice at the top as #1. 0 Apply by the deadline, December 2, 2019. Be sure to click the “Submit Application” button. We’re here to help! If you need support with MySchools or have questions about high school admissions: 0 Talk to your school counselor. 0 Call us at 718-935-2009. 0 Visit a Family Welcome Center—locations are listed on the inside back cover of this guide. ABOUT THE COVER Student: Nova Stanley | Teacher: Carl Landegger | Principal: Manuel Ureña Each year, the NYC Department of Education and Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum partner on a cover design challenge for public high school students. This book’s cover was designed by Nova Stanley, a student at High School of Art and Design. -

DBN School Name Type Principal Name 01M184 P.S

DBN School Name Type Principal Name 01M184 P.S. 184m Shuang Wen K-8 Ling Ling Chou 01M696 Bard High School Early College High school Raymond Peterson 02M047 47 The American Sign Language and English Secondary School Secondary School Watfa A. Shama 02M300 Urban Assembly School of Design and Construction, The High school Mathew Willoughby 02M303 Facing History School, The High school Gillian Smith 02M305 Urban Assembly Academy of Government and Law, The High school David P. Glasner 02M308 Lower Manhattan Arts Academy High school John Wenk Junior High-Intermediate- 02M312 New York City Lab Middle School for Collaborative Studies Middle Megan Adams 02M316 Urban Assembly School of Business for Young Women, the High school Patricia Minaya 02M347 The 47 American Sign Language & English Lower School K-8 Dave Bowell 02M376 NYC iSchool High school Mary Moss/ Alisa Berger 02M393 BUSINESS OF SPORTS SCHOOL High school Joshua Solomon 02M394 EMMA LAZARUS HIGH SCHOOL High school Melody Kellogg 02M399 THE HIGH SCHOOL FOR LANGUAGE AND DIPLOMACY High school Santiago Mayol 02M412 N.Y.C. Lab School for Collaborative Studies High school Brooke Jackson 02M418 Millennium High School High school Robert Rhodes 02M422 Quest to Learn Elementary ELISA ARAGON 02M542 Manhattan Bridges High School High school Mirza Sanchez Medina 02M551 New York Harbor School High school Nathan Dudley 02M560 High School M560 - City As School High school Antoniette Scarpinato 02M586 Harvey Milk High School High school ALAN NOLAN 02M615 Chelsea Career and Technical Education High School High school Brian Rosenbloom 03M166 P.S. 166 The Richard Rodgers School of The Arts and Technology Elementary Debbie J.