Chapter Nine

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rosella Norwood Gampola Do. Kadugannawa Nawalapitiya

IST of Persons in the Central Province qualified to serve as Jurors and Assessors, under the provision! L of the 257th section of the Ordinance No. 15 of 1898 (Criminal Procedure Code) for the year 1908. [N.B.—The letter s prefixed to a name signifies that the person is qualified to serve both as a Special and an Ordinary (English-speaking) Juror. The mark * prefixed to a name denotes a fresh name added (Section 258, Criminal Procedure Code).] ENGLISH-SPEAKING JURORS. 5 Acton, C. J., superintendent, S Aste, P. H., planter, Bin-oya (in 1 Stonyhurst and Orwell Gampola Europe) Rosella Adams, P. C., Wategodaestate Matale * Astell, A., planter, Gleneaim Norwood Agar, Roper, planter, Logie Talawakele * Astell, T. W., planter, Gangawatte Maskeliya * Agar, J., planter, Choisy Pundalu-oya Atkin, R.L., planter, Dandukalawe Hatton s Aitken, W. H., planter, Glen- Atkinson, P., Sinayapitiya Gampola cairn Norwood Atkins. A. D., Cleveland do. Alger, A., Iona Agrapatana Atkinson, R. S., proprietory, s Alleyn, H. M., planter, Choisy Pundalu-oya planter, Heatherton (in Europe) Arabegama Allison, J. A. W., Oodewelle Kandy Avery, W., Oswald, superintendent Allon, T. B., Miller & Co. do. Kumaragala Kadugannawa S Alston, G. C., planter, Queensland S Aymer, J., Goorookoya Nawalapitiya (in England) Maskeliya Badcock, R. G. R., Eildon Hall Lindula Alston,-R. G. F., planter, Hornsey Dikoya Badelay, C. F. B., planter, Erls* Alwis, D. L. de, clerk, Mercantile j mere Dikoya Bank of India Kandy | (Udu Pustel- Anderson, C. P., planter, Bandara- | lawa and a SL u, G. S. junior, Ttenp K S a k .I . ' S =“«<*■ C W*“ “ » t d . -

Update UNHCR/CDR Background Paper on Sri Lanka

NATIONS UNIES UNITED NATIONS HAUT COMMISSARIAT HIGH COMMISSIONER POUR LES REFUGIES FOR REFUGEES BACKGROUND PAPER ON REFUGEES AND ASYLUM SEEKERS FROM Sri Lanka UNHCR CENTRE FOR DOCUMENTATION AND RESEARCH GENEVA, JUNE 2001 THIS INFORMATION PAPER WAS PREPARED IN THE COUNTRY RESEARCH AND ANALYSIS UNIT OF UNHCR’S CENTRE FOR DOCUMENTATION AND RESEARCH ON THE BASIS OF PUBLICLY AVAILABLE INFORMATION, ANALYSIS AND COMMENT, IN COLLABORATION WITH THE UNHCR STATISTICAL UNIT. ALL SOURCES ARE CITED. THIS PAPER IS NOT, AND DOES NOT, PURPORT TO BE, FULLY EXHAUSTIVE WITH REGARD TO CONDITIONS IN THE COUNTRY SURVEYED, OR CONCLUSIVE AS TO THE MERITS OF ANY PARTICULAR CLAIM TO REFUGEE STATUS OR ASYLUM. ISSN 1020-8410 Table of Contents LIST OF ACRONYMS.............................................................................................................................. 3 1 INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................... 4 2 MAJOR POLITICAL DEVELOPMENTS IN SRI LANKA SINCE MARCH 1999................ 7 3 LEGAL CONTEXT...................................................................................................................... 17 3.1 International Legal Context ................................................................................................. 17 3.2 National Legal Context........................................................................................................ 19 4 REVIEW OF THE HUMAN RIGHTS SITUATION............................................................... -

( NAWALAPITIYA-NANCOYA SECTION of 4Fle MMES

▪ 396 CEYLON GOVERNMENT RAILWAYS. Statement showing RECEIPTS, 'WORKING EXPENSES, &c., of Railway between Colombo and Kalutara from opening to 1884. pi ..- C* •i Ool %I : .; k. i g i ,., -6'.. Et Z 0 :;,.. := 2. _ e> ial ;t! . ii, ,m.. •4 ''.:0 Et -ri FL c, 0 •Tii 24' "5 to 4 i ..T..cp ,t...<1 ....-01 0 E--ig 1--, .15t.:1 -__ 1877 144,878 103,410 0 .„ =Xi 1878 184891 130,5S0 1771; 70-6 :14g 2'74.8 1879 278,010 197,158 261: 70-9 130,852 ;.75 1880 301,791 232,231 Iv ; 27t 77 69,561 -r - 3. 1881 273,484 209,5435 if 0 27 76.6 63,919 2.9 1882 274,513 217,919 ' --,:;.F.., 27 71r4 54,594 26 1883 301,944 263,641 4 27, 89.3 47,459 .,.2 1884 282,661 219,183 ... 27 77'5 63,478 2g ---_-- -__ '1' Opened 1st Mural to Muratuwa. I Opened 1st September to Panadure. .;. Opened 2dsd September to Kulutarn. Statement showing RECEIPTS, WORKING ExPnxsEs, &c., of Railway. between /Candy and Miztate from 02/ening to lt,,S4. ' ' ..... ,.., ,5' 0 I2 o O ,i; E3 s? 92 6 ; 0 s; ..... ▪ iii et-o 203'g 51 t f..: 11 55. 71A t. 8 g >' • iD ,g1 T:5 % -6 o 3 '':, t. ri 4.; ?4 El.= H.F. 4 F. • P-■ - - - ro = o 18801. 35,312 28,611 o .;5:5 17i* 81.0 Nil. 1881 126,803 137,527 =7,,.:1 f I 1085 Nil. 1882 107,942 114,944 c. -

THE CEYLON GOVERNMENT GAZETTE No

THE CEYLON GOVERNMENT GAZETTE No. 10,462 —FRIDAY, OCTOBER 10, 1052 Published by Authority PART VI-LIST OF JURORS AND ASSESSORS (Separate paying is given to each P ait m order that it mat/ be filed separately) MIDLAND CIRCUIT 26 Amaradasa, Balage Wilson, Teamaker, Atta- bagie Group, Gampola CENTRAL PROVINCE— Kandy District 27 Ambalavanar, P., Head Clerk, National Bank of India Ltd , Kandy LIST of persons in the Central Province, residing 28 Am banpola, D. G , Clerk, D R. C., P. W. D., within a line of 30 miles radius from Kandy or 3 miles K a rd y of a Railway Station, who are qualified to serve as 29 Amerasekera, Karunagala Pathiranage Jurors and Assessors at Kandy, under the provision of Suwaris, Teacher, Dharmara.ia College, the Criminal Procedure Code for the year July, 1952, K andy to June, 1953. • 11 30 Amerasekera, Verahennidege Ariya, Man N B.— The Jurors numbered m a separate senes, on ager, Phoenix Studio, Ward Street, the left of those indicating Ordinary Jurors, are qualified K andy to serve as Special Jurors. 12 31 Amerasekera, Alexander Merrill, Superin tendent, Coolbawa, Nawalapitiya 13 32 Amerasekera, Eric Mervyn, Proprietory ENGLISH-SPEAKING JURORS Planter, Rest Harrow, Wattegama I Abdeen, M L. J., Landed Proprietor, 39, 33 Amerasinghe, Arthur Michael Perera, Illawatura, Gampola Superintendent, Pilessa, Mawatagama 1 2 Abdeen, O. Z., Landed Proprietor, • 68/5, 14 34 Amerasinghe, R. M., Teacher, St. Sylvesters Illawatura, Gampola College, Kandy 3 Abdeen, E. S. Z., Head Clerk, 218, Kandy 15 35 Amukotuwa, Nandasoma, Proprietory Road, Gampola Planter, Herondale Estate, Nawalapitiya 2. -

Urban Development, Human Settlements and Economic Infrastructure

Sector Vulnerability Profile: Urban Development, Human Settlements and in Sri Lanka Climate Change Vulnerability Economic Infrastructure Supplementary Document to: The National Climate Change Adaptation Strategy for Sri Lanka 2011 to 2016 Sector Vulnerability Profile: Urban Development, Human Settlements and Economic Infrastructure SVP Development Team Nayana Mawilmada - Team Leader/Strategic Planning Specialist Sithara Atapattu - Deputy Team Leader/Coastal Ecologist Jinie Dela - Environmental Specialist Nalaka Gunawardene - Communications Specialist Buddhi Weerasinghe - Communications Specialist Mahakumarage Nandana - GIS Specialist Aloka Bellanawithana - Project Assistant Ranjith Wimalasiri - EMO/Project Counterpart – Administration and Coordination Nirosha Kumari - EMO/Project Counterpart – Communications We acknowledge and appreciate all support provided by the Climate Change Secretariat, Ministry of Environment, SNC Project Team, UDA, NPPD, NBRO, Min. of Transport, CCD, RDA, SLTDA, CEB, Water Resources Board and the many other stakeholders who have contributed to this document. Refer Appendix E for the full list of stakeholders consulted during SVP preparation. Urban Development, Human Settlements and Economic Infrastructure SVP – Parts I & II Sector Vulnerability Profile on Urban Development, Human Settlements and Economic Infrastructure Table of Contents List of Boxes ________________________________________________________________________ iii List of Figures _______________________________________________________________________ -

Dealer Centers

Mobitel Branches Addresses Monday to Friday Saturday Sunday From To From To From To Mobitel Flagship Centre No. 108, W.A.D. Ramanayake Mw, Colombo 2 8.00 A.M. 7.00 P.M. 9.00 A.M. 5.00 P.M. 9.00 A.M. 5.00 P.M. M3 Experience Centre Excel World, 338, T.B. Jayah Mw, Colombo 10 9.30 A.M. 8.00 P.M. 9.30 A.M. 11.00 P.M. 9.30 A.M. 11.00 P.M. Colombo Branch No. 30, Queens Rd, Colombo 3 8.00 A.M. 6.00 P.M. 9.00 A.M. 5.00 P.M. 10.00 A.M. 5.00 P.M. Airport Arrival Branch Arrival Public Concourse, BIA, Katunayake 24 Hours Open Airport Departure Branch Shop No. 10, Departure Concourse, BIA, Katunayake Following Mobiltel Branches will be open on Sundays only for Registration/Re-Registration Anuradhapura Branch 213/7, Dhamsiri Building, Bank Place, Main Street, Anuradhapura 8.00 A.M. 6.00 P.M. 9.00 A.M. 4.00 P.M. *9.00 A.M. 4.00 P.M. Kandy Branch 141, Kotugodella Street, Kandy 8.00 A.M. 6.00 P.M. 9.00 A.M. 4.00 P.M. *9.00 A.M. 4.00 P.M. Kurunegala Branch 180C, Colombo Rd, Kurunegala 8.00 A.M. 6.00 P.M. 9.00 A.M. 4.00 P.M. *9.00 A.M. 4.00 P.M. Matara Branch No. 15, LGJ Building, Beach Road, Matara 8.00 A.M. -

Areas Declared Under Urban Development Authority

Point Pedro UC Velvetithurei UC!. !. !. Vadamarachchi PS Valikaman North 8 !. 3 !. 4 B Vadamaradchi South West Kankesanthurai PS Ton daima !. nar d Valla a i Tun o nal ai Roa R d B4 Valikaman West li 17 a !. l d Karainagar PS a a Total Declared Area P o - !. a P R u fn tt i seway a ur a igar Cau J -M h a c Karan e e h Kas sa c ad l o ai Valikaman South West a Roa i K R - d !. o d a m Local Authorities Total LA Declared LA Declared GND's a d a o Valikaman South m R a i !. k a i r d u Jaffna PS Ealuvaitivu o h P t !. K o MC 24 24 712 !. Kayts PS n - in a y t l P V s !. o e e l a Thenmaratchi PS d l u a k ro n n !. P -M a a Analaitivu i u - K r K u UC 41 41 514 !. Jaffna MC th a y B N a y a e av n t !Ha a Chavakachcheri UC k s w ch tku e R e l r s Ro i-K !. n o u a a i R a a d ra o d C iti a i vu d PS 276 203 6837 a -M n a Velanai PS n n a na d y!. P r a a Ro o w a R se d i au d C a ivu y ut la Nainaitivu d a ku T !. -

Of Sri Lanka: a Taxonomic Research Summary and Updated Checklist

ZooKeys 967: 1–142 (2020) A peer-reviewed open-access journal doi: 10.3897/zookeys.967.54432 CHECKLIST https://zookeys.pensoft.net Launched to accelerate biodiversity research The Ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) of Sri Lanka: a taxonomic research summary and updated checklist Ratnayake Kaluarachchige Sriyani Dias1, Benoit Guénard2, Shahid Ali Akbar3, Evan P. Economo4, Warnakulasuriyage Sudesh Udayakantha1, Aijaz Ahmad Wachkoo5 1 Department of Zoology and Environmental Management, University of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka 2 School of Biological Sciences, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong SAR, China3 Central Institute of Temperate Horticulture, Srinagar, Jammu and Kashmir, 191132, India 4 Biodiversity and Biocomplexity Unit, Okinawa Institute of Science and Technology Graduate University, Onna, Okinawa, Japan 5 Department of Zoology, Government Degree College, Shopian, Jammu and Kashmir, 190006, India Corresponding author: Aijaz Ahmad Wachkoo ([email protected]) Academic editor: Marek Borowiec | Received 18 May 2020 | Accepted 16 July 2020 | Published 14 September 2020 http://zoobank.org/61FBCC3D-10F3-496E-B26E-2483F5A508CD Citation: Dias RKS, Guénard B, Akbar SA, Economo EP, Udayakantha WS, Wachkoo AA (2020) The Ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) of Sri Lanka: a taxonomic research summary and updated checklist. ZooKeys 967: 1–142. https://doi.org/10.3897/zookeys.967.54432 Abstract An updated checklist of the ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) of Sri Lanka is presented. These include representatives of eleven of the 17 known extant subfamilies with 341 valid ant species in 79 genera. Lio- ponera longitarsus Mayr, 1879 is reported as a new species country record for Sri Lanka. Notes about type localities, depositories, and relevant references to each species record are given. -

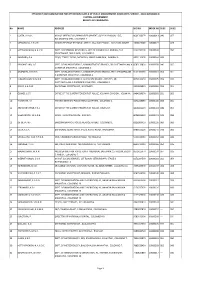

Bba `10 Students` Database

BBA `10 STUDENTS` DATABASE No Reg No Full Name Address Phone No 001 A/10/BBA/001 MOHAMAD NAWAZ MOHAMAD AATHIF 635 D/1 , MALWATTE , MALWANA, 0112570173 365/4 , BULUGOHATHENNA, AKURANA, 002 A/10/BBA/002 NISAF MOHAMMED AMINA KANDY 0773889016 OLIPHANT ESTATE , UPPER DIVITION, 003 A/10/BBA/003 KRISHNAMENON ANANTHAKRISHNAN NUWARA ELIYA, 0525615991 004 A/10/BBA/004 KETAKANDURE GEDARA ANURASIRI DELPATHKADA, PALLEBOWALA, , 0757813834 9-4B POLICE QUARTERS, BOGAMBARA, 005 A/10/BBA/005 AMBALANDORA GEDARA NILUSHA KUMARI ARIYASENA KANDY, 0719111243 006 A/10/BBA/006 MOHAMED LAFEER MOHAMED ARSHAD 1-1 IHALAWELLA , KENGALLA, , 0814928350 42 MUHANDIRAMS ROAD, KOLLUPITIYA, 007 A/10/BBA/007 AROSH STEPHEN AZARIAH COLOMBO 03, 0755547184 IHALA ULVITA GEDARA SEEVALIE ANURUDDHA DAMBAGALLA, NAYAPANA JANAPADAYA, 008 A/10/BBA/008 BAMUNUHENDARA GAMPOLA, 0817900060 ABEYSINGHE MUDIYANSELAGE HARSHANI 152-B, HARSHANI NIWASA, UDUPIHILLA, 009 A/10/BBA/009 MADUMALI BANDARA MATALE 0662224472 010 A/10/BBA/010 ILANKOON MUDIYANSELAGE CHANAKA DILSHAN BANDARA DHOMBAWELA, MAHAWELA, MATALE, 0663007381 AMBALIYADDA BAKERY, AMBALIYADDA, 011 A/10/BBA/011 PALIHANA RALALAGE CHAMINDA JANAKA BANDARA HANGURANKETHA, 0729672136 NO.224 , ANGURUWELLA ROAD, 012 A/10/BBA/012 BADURUZ ZAMAN SHAKEELA BANU GANITHAPURA, WARAKAPOLA 0353353946 013 A/10/BBA/013 MOHAMED JABIR ASMA BEGUM 88/1 , MATALE ROAD, AKURANA ., 0812300168 17-12, SRI SANGABO ROAD, KAWDANA, 014 A/10/BBA/014 KAGGODA ARACHCHIGE DILAN CHAMAL DEHIWALA 0728491114 015 A/10/BBA/015 PATABANDI MADDUMAGE THILINI CHATHURIKA 45, DOLOSBAGE ROAD, -

1 1. Background the Heavy Loss of Life As Well As the Unprecedented Damage to Property and Infrastructure Resulting from Landsli

VAT Asia Case Study 2 LANDSLIDE HAZARD ZONATION MAPPING AND MITIGATION IN SRI LANKA SRI LANKA URBAN MULTI-HAZARD DISASTER MITIGATION PROJECT (SLUMDMP) 1. Background The heavy loss of life as well as the unprecedented damage to property and infrastructure resulting from landslides during the monsoon periods in the years of 1968 and 1986 prompted the Government of Sri Lanka to take serious notes of the losses and initiate appropriate measures for the reduction of the impact of landslides. In 1990, the National Building Research Organization (NBRO) proposal on implementing a comprehensive program to identify the vulnerable areas to reduce the vulnerability to landslide was accepted by UNDP and UNCHS who agreed to provide the technical and financial assistance, this initiated a hazard zonation program to identify landslide areas under the “Lanslide Hazard Zonation Mapping Project (LHMP)”. This project was implemented in seven areas: Badulla, Nuwara Eliya, Ratnapura, Kegalle, Kandy, Matale, Kalutara. In order to integrate these efforts with the regional and urban planning process, Sri Lanka Urban Multi hazard Disaster Mitigation Project was implemented on 1st October 1997. Ratnapura Town was selected as the site for the demonstration project and it was further replicated in other towns as of part of Sri Lanka Urban Multi-hazard Disaster Mitigation Project (SLUMDMP), implemented by Centre for Housing Planning and Building (CHPB) in partnership with NBRO and Urban Development Authority (UDA), under the Asian Urban Disaster Mitigation Program (AUDMP) of ADPC. This case study reports on the risk assessment methodology undertaken under the SLUMDMP with the application of rapid assessment in Ratnapura Municipality. -

EB PMAS Class 2 2011 2.Pdf

EFFICIENCY BAR EXAMINATION FOR OFFICERS IN CLASS II OF PUBLIC MANAGEMENT ASSISTANT'S SERVICE - 2011(II)2013(2014) CENTRAL GOVERNMENT RESULTS OF CANDIDATES No NAME ADDRESS NIC NO INDEX NO SUB1 SUB2 1 COSTA, K.A.G.C. M/Y OF DEFENCE & URBAN DEVELOPMENT, SUPPLY DIVISION, 15/5, 860170337V 10000013 040 057 BALADAKSHA MW, COLOMBO 3. 2 MEDAGODA, G.R.U.K. INLAND REVENUE REGIONAL OFFICE, 334, GALLE ROAD, KALUTARA SOUTH. 745802338V 10000027 --- 024 3 HETTIARACHCHI, H.A.S.W. DEPT. OF EXTERNAL RESOURCES, M/Y OF FINANCE & PLANNING, THE 823273010V 10000030 --- 050 SECRETARIAT, 3RD FLOOR, COLOMBO 1. 4 BANDARA, P.A. 230/4, TEMPLE ROAD, BATAPOLA, MADELGAMUWA, GAMPAHA. 682113260V 10000044 ABS --- 5 PRASANTHIKA, L.G. DEPT. OF INLAND REVENUE, ADMINISTRATIVE BRANCH, SRI CHITTAMPALAM A 858513383V 10000058 040 055 GARDINER MAWATHA, COLOMBO 2. 6 ATAPATTU, D.M.D.S. DEPT. OF INLAND REVENUE, ADMINISTRATION BRANCH, SRI CHITTAMPALAM 816130069V 10000061 054 051 A GARDINER MAWATHA, COLOMBO 2. 7 KUMARIHAMI, W.M.S.N. DEPT. OF INLAND REVENUE, ACCOUNTS BRANCH, POB 515, SRI 867010025V 10000075 059 070 CHITTAMPALAM A GARDINER MAWATHA, COLOMBO 2. 8 JENAT, A.A.D.M. DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT, NEGOMBO. 685060892V 10000089 034 051 9 GOMES, J.S.T. OFFICE OF THE SUPERINTENDENT OF POLICE, KELANIYA DIVISION, KELANIYA. 846453857V 10000092 031 052 10 HARSHANI, A.I. FINANCE BRANCH, POLICE HEAD QUARTERS, COLOMBO 1. 827122858V 10000104 064 061 11 ABHAYARATHNE, Y.P.J. OFFICE OF THE SUPERINTENDENT OF POLICE, KELANIYA. 841800117V 10000118 049 057 12 WEERAKOON, W.A.D.B. 140/B, THANAYAM PLACE, INGIRIYA. 802893329V 10000121 049 068 13 DE SILVA, W.I. -

Sri Lanka 2030

Implementation of the National Physical Planning Policy and Plan Sri Lanka 2010-2030 Project Proposals National Physical Planning Department April 2010 Implementation of the National Physical Planning Policy and Plan Sri Lanka 2010-2030 Project Proposals National Physical Planning Department 5th Floor Sethsiripaya Battaramulla Sri Lanka Telephone: (011) 2872046Fax: (011)2872061 E-mail: [email protected] April 2010 INTRODUCTION The purpose of this document is to demonstrate large scale public and private investment opportunities for infrastructure and urban development projects for the next 20 years and beyond. Such projects are listed to indicate to potential investors and donors the advantages of a planned Sri Lanka. This document consists of the following sections: Section 1: Introduction to the National Physical Planning Policy and Plan Section 2: International and Asian Context Section 3: Projects in International and Asian Context Section 4: National Projects Section 5: Regional Projects The document outlines the National Physical Planning Policy and Plan and is published with the following specific objectives: 1. As a list of large scale infrastructure and urban development projects available for investment or donor / sponsorship; 2. As a guide to government agencies for future planning of their sectoral programmes; 3. As a guide to policy makers; 4. As an informative document to the general public. Contents Page Contents Page Map 10: Proposed Outward Movement of Population and Plantations 15 Section 1: Introduction to the National Physical Planning Policy 5 Map 11: Settlement Pattern and Schematic Location of Metro Regions 16 and Plan Map 1 2 : Existing Roads – RDA Proposals 18 Map 13: Proposed Expressways and Highways 18 Section 2: International and Asian Context 7 Map 14: Existing and Proposed Roads and Rail 19 Section 3: Projects in International and Asian Context 8 Map 15: Existing and Proposed Railway Network 19 1.