Update UNHCR/CDR Background Paper on Sri Lanka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Horana Plantations Plc Horan a Plant a Tions P L

HORANA PLANTATIONS PLC ANNUAL REPORT 2017/18 HORANA PLANTATIONS P PLANTATIONS HORANA Think L C | New www.horanaplantations.com ANNU A L REPO R T 2017/18 Contents Corporate Information COMPANY NAME REGISTERED OFFICE ADDRESS LEGAL ADVISORS Horana Plantations PLC No.400 Deans Road, Nithi Murugesu & Associates About Horana Plantations 2 Colombo 10. Attorneys-at-Law & Notaries Public Non-Financial Highlights 3 DOMICILE AND LEGAL FORM Telephone : 011 2627000 No.28 (Level 2) W.A.D.Ramanayake Financial Highlights 4 Horana Plantations PLC is a Quoted 011 2627301-7322 Mawatha, Chairman’s Message 6 Public Company with limited liability, Facsimile: 011 2627323 Colombo 2. Managing Director’s Review of Operations 10 Incorporated and domiciled in Sri Lanka, E Mail: [email protected] Board of Directors 16 under the Companies Act No.17 of [email protected] TAX ADVISORS Management Team 18 1982 in terms of the provisions of the Web: www.horanaplantations.com Nanayakkara & Company Sustainability Report 20 Conversion of Public Corporations Chartered Accountants Statement of Corporate Governance 29 of Government Owned Business PARENT COMPANY 3rd Floor, Yathama Building Risk Management 34 Undertakings into Public Companies Act Vallibel Plantation Management Ltd No.142 Galle Road, Annual Report of the Board of Directors No.23 of 1987 and re-registered under No.400 Deans Road, Colombo 3. on the Affairs of the Company 35 the Companies Act No.7 of 2007 Colombo 10. Statement of Directors’ Responsibilities 39 BANKERS Report of the Remuneration Committee 40 DATE OF INCORPORATION ULTIMATE PARENT COMPANY OF THE Commercial Bank of Ceylon PLC Related Party Transactions Review 22nd June 1992 GROUP Hatton National Bank PLC Committee Report 41 Vallibel One PLC People’s Bank Audit Committee Report 43 REGISTRATION NUMBER Level 29, West Tower, Seylan Bank PLC PQ 126 World Trade Centre, Echelon Square, Financial Reports Colombo 1. -

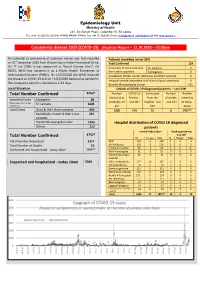

Epidemiology Unit

Epidemiology Unit Ministry of Health 231, De Saram Place, Colombo 10, Sri Lanka Tele: (+94 11) 2695112, 2681548, 4740490, 4740491, 4740492 Fax: (+94 11) 2696583 E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Web: www.epid.gov.lk Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) - Situation Report – 12.10.2020 – 10.00am An outbreak of pneumonia of unknown reason was first reported Patients identified in last 24H st on 31 December 2019 from Wuhan City in Hubei Province of China. Total Confirmed 124 th On 7 Jan 2020, it was diagnosed as “Novel Corona Virus”. On Returnees (+ close contacts) Sri Lankans 3 30/01, WHO has declared it as a Public Health Emergency of from other countries Foreigners 0 International Concern (PHEIC). On 11/02/2020 the WHO renamed Kandakadu Rehab. Center detainees and their contacts 0 the disease as COVID-19 and on 11/03/2020 declared as pandemic. Hospital samples (admitted with clinical signs/symptoms) 0 The incubation period is reported as 2-14 days. Brandix Minuwangoda cluster 121 Local Situation Details of COVID 19 diagnosed patients – Last 24H 4752* Number COVID 19 Discharged Number Number Total Number Confirmed inward as at Positive - from the of deaths inward as Imported Cases Foreigners 86 yesterday-10 last 24H hospital - last - last 24H at today- (Returnees from other Sri Lankans 1446 countries) am 24H 10 am Local Cases Navy & their close contacts 950 1308 124 10 0 1422** Kandakadu cluster & their close 651 contacts Brandix Minuwangoda cluster 1306 Hospital distribution of COVID 19 diagnosed Others 313 patients Inward Today -

World Bank Document

Document of The World Bank FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY Public Disclosure Authorized Report No: 3 8 147 - LK PROJECT APPRAISAL DOCUMENT ON A Public Disclosure Authorized PROPOSED CREDIT IN THE AMOUNT OF SDR 21.7 MILLION (US$32 MILLION EQUIVALENT) TO THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA FOR A PUTTALAM HOUSING PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized JANUARY 24,2007 Sustainable Development South Asia Region Public Disclosure Authorized This document has a restricted distribution and may be used by recipients only in the performance of their official duties. Its contents may not otherwise be disclosed without World Bank authorization. CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS (Exchange Rate Effective December 13,2006) Currency Unit = Sri Lankan Rupee 108 Rupees (Rs.) = US$1 US$1.50609 = SDR 1 FISCAL YEAR January 1 - December 31 ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS ADB Asian Development Bank LTF Land Task Force AG Auditor General LTTE Liberation Tigers ofTamil Eelam CAS Country Assistance Strategy NCB National Competitive Bidding CEB Ceylon Electricity Board NGO Non Governmental Organization CFAA Country Financial Accountability Assessment NEIAP North East Irrigated Agriculture Project CQS Selection Cased on Consultants Qualifications NEHRP North East Housing Reconstruction Program CSIA Continuous Social Impact Assessment NPA National Procurement Agency CSP Camp Social Profile NPV Not Present Value CWSSP Community Water Supply and Sanitation NWPEA North Western Provincial Environmental Act Project DMC District Monitoring Committees NWPRD NorthWest Provincial Roads Department -

Ruwanwella) Mrs

Lady Members First State Council (1931 - 1935) Mrs. Adline Molamure by-election (Ruwanwella) Mrs. Naysum Saravanamuttu by-election (Colombo North) (Mrs. Molamure was the first woman to be elected to the Legislature) Second State Council (1936 - 1947) Mrs. Naysum Saravanamuttu (Colombo North) First Parliament (House of Representatives) (1947 - 1952) Mrs. Florence Senanayake (Kiriella) Mrs. Kusumasiri Gunawardena by-election (Avissawella) Mrs. Tamara Kumari Illangaratne by-election (Kandy) Second Parliament (House of (1952 - 1956) Representatives) Mrs. Kusumasiri Gunawardena (Avissawella) Mrs. Doreen Wickremasinghe (Akuressa) Third Parliament (House of Representatives) (1956 - 1959) Mrs. Viviene Goonewardene (Colombo North) Mrs. Kusumasiri Gunawardena (Kiriella) Mrs. Vimala Wijewardene (Mirigama) Mrs. Kusuma Rajaratna by-election (Welimada) Lady Members Fourth Parliament (House of (March - April 1960) Representatives) Mrs. Wimala Kannangara (Galigomuwa) Mrs. Kusuma Rajaratna (Uva-Paranagama) Mrs. Soma Wickremanayake (Dehiowita) Fifth Parliament (House of Representatives) (July 1960 - 1964) Mrs. Kusuma Rajaratna (Uva-Paranagama) Mrs. Soma Wickremanayake (Dehiowita) Mrs. Viviene Goonewardene by-election (Borella) Sixth Parliament (House of Representatives) (1965 - 1970) Mrs. Sirima R. D. Bandaranaike (Attanagalla) Mrs. Sivagamie Obeyesekere (Mirigama) Mrs. Wimala Kannangara (Galigomuwa) Mrs. Kusuma Rajaratna (Uva-Paranagama) Mrs. Leticia Rajapakse by-election (Dodangaslanda) Mrs. Mallika Ratwatte by-election (Balangoda) Seventh Parliament (House of (1970 - 1972) / (1972 - 1977) Representatives) & First National State Assembly Mrs. Kusala Abhayavardhana (Borella) Mrs. Sirima R. D. Bandaranaike (Attanagalla) Mrs. Viviene Goonewardene (Dehiwala - Mt.Lavinia) Lady Members Mrs. Tamara Kumari Ilangaratne (Galagedera) Mrs. Sivagamie Obeyesekere (Mirigama) Mrs. Mallika Ratwatte (Balangoda) Second National State Assembly & First (1977 - 1978) / (1978 - 1989) Parliament of the D.S.R. of Sri Lanka Mrs. Sirima R. D. Bandaranaike (Attanagalla) Miss. -

Cover & Back of SLWC Volume 2

Assessment of Risks to Water Bodies due to Residues of Agricultural Fungicide in Intensive Farming Areas in the Up-country of Sri Lanka using an Indicator Model Ransilu C. Watawala1, Janitha A. Liyanage1 and Ananda Mallawatantri2 1Department of Chemistry, University of Kelaniya, Kelaniya, Sri Lanka 2United Nations Development Programme, Colombo, Sri Lanka Introduction Indiscriminate use of agrochemicals poses a major environmental threat to surface and groundwater. Intensive vegetable cultivation on the steep slopes of up-country hills requires extremely high levels of pesticides (insecticides and fungicides) and fertilizers to maintain high yields and profitability. Farmers do not necessarily follow the doses and frequencies recommended in the instructions but apply higher doses more frequently, as they believe that this will increase yields. The implications of these decisions are not considered by farmers due to the lack of information and understanding of the environmental pathways of chemicals after application. In addition, the methods available to account for the variability of soils, climate and other factors influencing the risk of pesticide use are complex. Potato cultivation in Nuwara Eliya, Bandarawela and Welimada Sri Lanka is a good example of the effects of excessive pesticide use. In these areas precipitation exceeds 1,830mm per annum and crops are affected by a number of diseases and insect attacks, such as late blight caused by Phytopthora infestance. The prevailing misty conditions also promote fungal growth requiring famers to use contact and systemic fungicides for prevention. Lack of understanding of pesticide pathways and the desire to ensure that the disease is under control often lead to overdoses and higher frequency application of pesticides. -

Rosella Norwood Gampola Do. Kadugannawa Nawalapitiya

IST of Persons in the Central Province qualified to serve as Jurors and Assessors, under the provision! L of the 257th section of the Ordinance No. 15 of 1898 (Criminal Procedure Code) for the year 1908. [N.B.—The letter s prefixed to a name signifies that the person is qualified to serve both as a Special and an Ordinary (English-speaking) Juror. The mark * prefixed to a name denotes a fresh name added (Section 258, Criminal Procedure Code).] ENGLISH-SPEAKING JURORS. 5 Acton, C. J., superintendent, S Aste, P. H., planter, Bin-oya (in 1 Stonyhurst and Orwell Gampola Europe) Rosella Adams, P. C., Wategodaestate Matale * Astell, A., planter, Gleneaim Norwood Agar, Roper, planter, Logie Talawakele * Astell, T. W., planter, Gangawatte Maskeliya * Agar, J., planter, Choisy Pundalu-oya Atkin, R.L., planter, Dandukalawe Hatton s Aitken, W. H., planter, Glen- Atkinson, P., Sinayapitiya Gampola cairn Norwood Atkins. A. D., Cleveland do. Alger, A., Iona Agrapatana Atkinson, R. S., proprietory, s Alleyn, H. M., planter, Choisy Pundalu-oya planter, Heatherton (in Europe) Arabegama Allison, J. A. W., Oodewelle Kandy Avery, W., Oswald, superintendent Allon, T. B., Miller & Co. do. Kumaragala Kadugannawa S Alston, G. C., planter, Queensland S Aymer, J., Goorookoya Nawalapitiya (in England) Maskeliya Badcock, R. G. R., Eildon Hall Lindula Alston,-R. G. F., planter, Hornsey Dikoya Badelay, C. F. B., planter, Erls* Alwis, D. L. de, clerk, Mercantile j mere Dikoya Bank of India Kandy | (Udu Pustel- Anderson, C. P., planter, Bandara- | lawa and a SL u, G. S. junior, Ttenp K S a k .I . ' S =“«<*■ C W*“ “ » t d . -

Beautification and the Embodiment of Authenticity in Post-War Eastern Sri Lanka

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Undergraduate Humanities Forum 2014-2015: Penn Humanities Forum Undergraduate Color Research Fellows 5-2015 Ornamenting Fingernails and Roads: Beautification and the Embodiment of Authenticity in Post-War Eastern Sri Lanka Kimberly Kolor University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/uhf_2015 Part of the Asian History Commons Kolor, Kimberly, "Ornamenting Fingernails and Roads: Beautification and the Embodiment of uthenticityA in Post-War Eastern Sri Lanka" (2015). Undergraduate Humanities Forum 2014-2015: Color. 7. https://repository.upenn.edu/uhf_2015/7 This paper was part of the 2014-2015 Penn Humanities Forum on Color. Find out more at http://www.phf.upenn.edu/annual-topics/color. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/uhf_2015/7 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ornamenting Fingernails and Roads: Beautification and the Embodiment of Authenticity in Post-War Eastern Sri Lanka Abstract In post-conflict Sri Lanka, communal tensions continue ot be negotiated, contested, and remade. Color codes virtually every aspect of daily life in salient local idioms. Scholars rarely focus on the lived visual semiotics of local, everyday exchanges from how women ornament their nails to how communities beautify their open—and sometimes contested—spaces. I draw on my ethnographic data from Eastern Sri Lanka and explore ‘color’ as negotiated through personal and public ornaments and notions of beauty with a material culture focus. I argue for a broad view of ‘public,’ which includes often marginalized and feminized public modalities. This view also explores how beauty and ornament are salient technologies of community and cultural authenticity that build on histories of ethnic imaginaries. -

CHAP 9 Sri Lanka

79o 00' 79o 30' 80o 00' 80o 30' 81o 00' 81o 30' 82o 00' Kankesanturai Point Pedro A I Karaitivu I. Jana D Peninsula N Kayts Jana SRI LANKA I Palk Strait National capital Ja na Elephant Pass Punkudutivu I. Lag Provincial capital oon Devipattinam Delft I. Town, village Palk Bay Kilinochchi Provincial boundary - Puthukkudiyiruppu Nanthi Kadal Main road Rameswaram Iranaitivu Is. Mullaittivu Secondary road Pamban I. Ferry Vellankulam Dhanushkodi Talaimannar Manjulam Nayaru Lagoon Railroad A da m' Airport s Bridge NORTHERN Nedunkeni 9o 00' Kokkilai Lagoon Mannar I. Mannar Puliyankulam Pulmoddai Madhu Road Bay of Bengal Gulf of Mannar Silavatturai Vavuniya Nilaveli Pankulam Kebitigollewa Trincomalee Horuwupotana r Bay Medawachchiya diya A d o o o 8 30' ru 8 30' v K i A Karaitivu I. ru Hamillewa n a Mutur Y Pomparippu Anuradhapura Kantalai n o NORTH CENTRAL Kalpitiya o g Maragahewa a Kathiraveli L Kal m a Oy a a l a t t Puttalam Kekirawa Habarane u 8o 00' P Galgamuwa 8o 00' NORTH Polonnaruwa Dambula Valachchenai Anamaduwa a y O Mundal Maho a Chenkaladi Lake r u WESTERN d Batticaloa Naula a M uru ed D Ganewatta a EASTERN g n Madura Oya a G Reservoir Chilaw i l Maha Oya o Kurunegala e o 7 30' w 7 30' Matale a Paddiruppu h Kuliyapitiya a CENTRAL M Kehelula Kalmunai Pannala Kandy Mahiyangana Uhana Randenigale ya Amparai a O a Mah Reservoir y Negombo Kegalla O Gal Tirrukkovil Negombo Victoria Falls Reservoir Bibile Senanayake Lagoon Gampaha Samudra Ja-Ela o a Nuwara Badulla o 7 00' ng 7 00' Kelan a Avissawella Eliya Colombo i G Sri Jayewardenepura -

First Parliament (House of Representatives) 1947 - 1952 R

Deputy Speakers and Chairmen of Committees First Parliament (House of Representatives) 1947 - 1952 R. A. de Mel, M.P. 14 October 1947 - 23 August 1948 (Colombo South) H. W. Amarasuriya, M.P. 02 September 1948 - 14 December 1948 (Baddegama) Hon. Sir Albert F. Periris, M.P. 15 December 1948 - 13 February 1951 (Nattandiya) H. S. Ismail, MBE, M.P. 14 February 1951 - 08 April 1952 (Puttalam) Second Parliament (House of 1952 - 1956 Representatives) H. S. Ismail, MBE, M.P. 10 June 1952 - 18 February 1956 (Puttalam) Third Parliament (House of Representatives) 1956 - 1959 Piyasena Tennakoon, M.P. 20 April 1956 - 16 September 1958 (Kandy) R. S. Pelpola, M.P. 18 September 1958 - 05 December 1959 (Gampola) Fourth Parliament (House of March - April 1960 Representatives) R. S. Pelpola, M.P. 30 March 1960 - 23 April 1960 (Nawalapitiya) Fifth Parliament (House of Representatives) 1960 - 1964 Hugh Fernando, M.P. 05 August 1960 - 23 January 1964 (Wennappuwa) D. A. Rajapakse, M.P. 11 February 1964 - 12 November 1964 (Beliatte) Sixth Parliament (House of Representatives) 1965 - 1970 C. S. Shirley Corea, M.P. 05 April 1965 - 27 September 1967 (Chilaw) Deputy Speakers and Chairmen of Committees Sir Razik Fareed, OBE, M.P. 28 September 1967 - 28 February 1968 (Appointed Member) M. Sivasithamparam, M.P. 08 March 1968 - 25 March 1970 (Uduppiddi) Seventh Parliament (House of 1970 - 1972 Representatives) I. A. Cader, M.P. 07 June 1970 - 22 May 1972 (Beruwala) First National State Assembly 1972 - 1977 I. A. Cader, M.P. 22 May 1972 - 18 May 1977 (Beruwala) Second National State Assembly 1977 - 1978 M. -

Urban Transport System Development Project for Colombo Metropolitan Region and Suburbs

DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT URBAN TRANSPORT SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT PROJECT FOR COLOMBO METROPOLITAN REGION AND SUBURBS URBAN TRANSPORT MASTER PLAN FINAL REPORT TECHNICAL REPORTS AUGUST 2014 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY EI ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. JR 14-142 DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT URBAN TRANSPORT SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT PROJECT FOR COLOMBO METROPOLITAN REGION AND SUBURBS URBAN TRANSPORT MASTER PLAN FINAL REPORT TECHNICAL REPORTS AUGUST 2014 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT URBAN TRANSPORT SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT PROJECT FOR COLOMBO METROPOLITAN REGION AND SUBURBS Technical Report No. 1 Analysis of Current Public Transport AUGUST 2014 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY (JICA) ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. URBAN TRANSPORT SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT PROJECT FOR COLOMBO METROPOLITAN REGION AND SUBURBS Technical Report No. 1 Analysis on Current Public Transport TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 Railways ............................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 History of Railways in Sri Lanka .................................................................................................. 1 1.2 Railway Lines in Western Province .............................................................................................. 5 1.3 Train Operation ............................................................................................................................ -

Sri Lanka for the Clean Energy and Access Improvement Project

Sustainable Power Sector Support Project (RRP SRI 39415) Detailed Description of Project Components A. Transmission system strengthening 1. This component will contribute to a reliable, adequate and affordable power supply for sustainable economic growth and poverty reduction in Eastern, North Central, Southern and Uva provinces. The strengthened transmission system will alleviate existing sub- standard voltage conditions in Ampara district of the Eastern Province and provide increased load capacity in the Eastern, North Central, Southern and Uva provinces leading to improved efficiency and reliability in power supply. The component includes the following sub-projects: (i) New Galle Power Transmission Development: Construction of New Galle 3 x 31.5 megavolt ampere (MVA) 132/33 kilovolt (kV) grid substation and Ambalangoda-to- New Galle 40 kilometers (km) double circuit 132 kV transmission line: T1a: New 3 x 31.5 MVA 132/33 kV New Galle Grid Substation Construction of a new grid substation at Galle comprising: 132 kV double busbar switchyard with: o 4 feeder bays o 1 static VAR compensator bay +10 megavolt ampere reactive (MVAr) to - 20 MVAr for voltage support o 3 transformer bays o 1 bus-coupler bay o 3 x 31.5 MVA transformers 33 kV switchyard with: o 3 transformer bays o 2 bus-section bays o 10 feeder bays o 2 generator bays o 6 capacitor bays with total of 30 MVA capacitors for loss reduction Control room and all associated communications, protection and control. This substation is located adjacent to the existing Galle 132/33 kV substation, which is old and cannot be extended further. -

Sri Lanka – Tamils – Eastern Province – Batticaloa – Colombo

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: LKA34481 Country: Sri Lanka Date: 11 March 2009 Keywords: Sri Lanka – Tamils – Eastern Province – Batticaloa – Colombo – International Business Systems Institute – Education system – Sri Lankan Army-Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam conflict – Risk of arrest This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide information on the International Business Systems Institute in Kaluvanchikkudy. 2. Is it likely that someone would attain a high school or higher education qualification in Sri Lanka without learning a language other than Tamil? 3. Please provide an overview/timeline of relevant events in the Eastern Province of Sri Lanka from 1986 to 2004, with particular reference to the Sri Lankan Army (SLA)-Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) conflict. 4. What is the current situation and risk of arrest for male Tamils in Batticaloa and Colombo? RESPONSE 1. Please provide information on the International Business Systems Institute in Kaluvanchikkudy. Note: Kaluvanchikkudy is also transliterated as Kaluwanchikudy is some sources. No references could be located to the International Business Systems Institute in Kaluvanchikkudy. The Education Guide Sri Lanka website maintains a list of the “Training Institutes Registered under the Ministry of Skills Development, Vocational and Tertiary Education”, and among these is ‘International Business System Overseas (Pvt) Ltd’ (IBS).