Beautification and the Embodiment of Authenticity in Post-War Eastern Sri Lanka

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northern Sri Lanka Jane Derges University College London Phd In

Northern Sri Lanka Jane Derges University College London PhD in Social Anthropology UMI Number: U591568 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U591568 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Fig. 1. Aathumkkaavadi DECLARATION I, Jane Derges, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources I confirm that this has been indicated the thesis. ABSTRACT Following twenty-five years of civil war between the Sri Lankan government troops and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), a ceasefire was called in February 2002. This truce is now on the point of collapse, due to a break down in talks over the post-war administration of the northern and eastern provinces. These instabilities have lead to conflicts within the insurgent ranks as well as political and religious factions in the south. This thesis centres on how the anguish of war and its unresolved aftermath is being communicated among Tamils living in the northern reaches of Sri Lanka. -

Minutes of Parliament Present

(Ninth Parliament - First Session) No. 62.] MINUTES OF PARLIAMENT Thursday, March 25, 2021 at 10.00 a.m. PRESENT : Hon. Mahinda Yapa Abeywardana, Speaker Hon. Angajan Ramanathan, Deputy Chairperson of Committees Hon. Mahinda Amaraweera, Minister of Environment Hon. Dullas Alahapperuma, Minister of Power Hon. Mahindananda Aluthgamage, Minister of Agriculture Hon. Udaya Gammanpila, Minister of Energy Hon. Dinesh Gunawardena, Minister of Foreign and Leader of the House of Parliament Hon. (Dr.) Bandula Gunawardana, Minister of Trade Hon. Janaka Bandara Thennakoon, Minister of Public Services, Provincial Councils & Local Government Hon. Nimal Siripala de Silva, Minister of Labour Hon. Vasudeva Nanayakkara, Minister of Water Supply Hon. (Dr.) Ramesh Pathirana, Minister of Plantation Hon. Johnston Fernando, Minister of Highways and Chief Government Whip Hon. Prasanna Ranatunga, Minister of Tourism Hon. C. B. Rathnayake, Minister of Wildlife & Forest Conservation Hon. Chamal Rajapaksa, Minister of Irrigation and State Minister of National Security & Disaster Management and State Minister of Home Affairs Hon. Gamini Lokuge, Minister of Transport Hon. Wimal Weerawansa, Minister of Industries Hon. (Dr.) Sarath Weerasekera, Minister of Public Security Hon. M .U. M. Ali Sabry, Minister of Justice Hon. (Dr.) (Mrs.) Seetha Arambepola, State Minister of Skills Development, Vocational Education, Research and Innovation Hon. Lasantha Alagiyawanna, State Minister of Co-operative Services, Marketing Development and Consumer Protection ( 2 ) M. No. 62 Hon. Ajith Nivard Cabraal, State Minister of Money & Capital Market and State Enterprise Reforms Hon. (Dr.) Nalaka Godahewa, State Minister of Urban Development, Coast Conservation, Waste Disposal and Community Cleanliness Hon. D. V. Chanaka, State Minister of Aviation and Export Zones Development Hon. Sisira Jayakody, State Minister of Indigenous Medicine Promotion, Rural and Ayurvedic Hospitals Development and Community Health Hon. -

Migration and Morality Amongst Sri Lankan Catholics

UNLIKELY COSMPOLITANS: MIGRATION AND MORALITY AMONGST SRI LANKAN CATHOLICS A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Bernardo Enrique Brown August, 2013 © 2013 Bernardo Enrique Brown ii UNLIKELY COSMOPOLITANS: MIGRATION AND MORALITY AMONGST SRI LANKAN CATHOLICS Bernardo Enrique Brown, Ph.D. Cornell University, 2013 Sri Lankan Catholic families that successfully migrated to Italy encountered multiple challenges upon their return. Although most of these families set off pursuing very specific material objectives through transnational migration, the difficulties generated by return migration forced them to devise new and creative arguments to justify their continued stay away from home. This ethnography traces the migratory trajectories of Catholic families from the area of Negombo and suggests that – due to particular religious, historic and geographic circumstances– the community was able to develop a cosmopolitan attitude towards the foreign that allowed many of its members to imagine themselves as ―better fit‖ for migration than other Sri Lankans. But this cosmopolitanism was not boundless, it was circumscribed by specific ethical values that were constitutive of the identity of this community. For all the cosmopolitan curiosity that inspired people to leave, there was a clear limit to what values and practices could be negotiated without incurring serious moral transgressions. My dissertation traces the way in which these iii transnational families took decisions, constantly navigating between the extremes of a flexible, rootless cosmopolitanism and a rigid definition of identity demarcated by local attachments. Through fieldwork conducted between January and December of 2010 in the predominantly Catholic region of Negombo, I examine the work that transnational migrants did to become moral beings in a time of globalization, individualism and intense consumerism. -

CHAP 9 Sri Lanka

79o 00' 79o 30' 80o 00' 80o 30' 81o 00' 81o 30' 82o 00' Kankesanturai Point Pedro A I Karaitivu I. Jana D Peninsula N Kayts Jana SRI LANKA I Palk Strait National capital Ja na Elephant Pass Punkudutivu I. Lag Provincial capital oon Devipattinam Delft I. Town, village Palk Bay Kilinochchi Provincial boundary - Puthukkudiyiruppu Nanthi Kadal Main road Rameswaram Iranaitivu Is. Mullaittivu Secondary road Pamban I. Ferry Vellankulam Dhanushkodi Talaimannar Manjulam Nayaru Lagoon Railroad A da m' Airport s Bridge NORTHERN Nedunkeni 9o 00' Kokkilai Lagoon Mannar I. Mannar Puliyankulam Pulmoddai Madhu Road Bay of Bengal Gulf of Mannar Silavatturai Vavuniya Nilaveli Pankulam Kebitigollewa Trincomalee Horuwupotana r Bay Medawachchiya diya A d o o o 8 30' ru 8 30' v K i A Karaitivu I. ru Hamillewa n a Mutur Y Pomparippu Anuradhapura Kantalai n o NORTH CENTRAL Kalpitiya o g Maragahewa a Kathiraveli L Kal m a Oy a a l a t t Puttalam Kekirawa Habarane u 8o 00' P Galgamuwa 8o 00' NORTH Polonnaruwa Dambula Valachchenai Anamaduwa a y O Mundal Maho a Chenkaladi Lake r u WESTERN d Batticaloa Naula a M uru ed D Ganewatta a EASTERN g n Madura Oya a G Reservoir Chilaw i l Maha Oya o Kurunegala e o 7 30' w 7 30' Matale a Paddiruppu h Kuliyapitiya a CENTRAL M Kehelula Kalmunai Pannala Kandy Mahiyangana Uhana Randenigale ya Amparai a O a Mah Reservoir y Negombo Kegalla O Gal Tirrukkovil Negombo Victoria Falls Reservoir Bibile Senanayake Lagoon Gampaha Samudra Ja-Ela o a Nuwara Badulla o 7 00' ng 7 00' Kelan a Avissawella Eliya Colombo i G Sri Jayewardenepura -

A Case Study of Kalmunai Municipal Area in Ampara District

Available online at www.worldscientificnews.com WSN 59 (2016) 35-51 EISSN 2392-2192 Emerging challenges of urbanization: a case study of Kalmunai municipal area in Ampara district M. B. Muneera* and M. I. M. Kaleel** Department of Geography, Faculty of Arts and Culture South Eastern University of Sri Lanka, Sri Lanka *,**E-mail address: [email protected] , [email protected] ABSTRACT Urban population refers to people living in urban areas as defined by national statistical offices. It is calculated using World Bank population estimates and urban ratios from the United Nations World Urbanization Prospects. Aggregation of urban and rural population may not add up to total population because of different country coverages. The study based on the Kalmunai MC area and the main objective of this study is to identify the emerging challenges of urbanization in the study area. The study used the methodologies are primary data collection as questionnaire, interview, observation and the secondary data collection and SWOT analysis to made for getting the better result. The study finds that the SWOT analysis process provided a number of results and ideas for future planning. Collecting the results around themes has highlighted the breadth of ideas within KMC. A number of common issues emerged which require immediate action and clearly relate to developing KMC as a resilient urban. However, to generate energy requires heap quantities of plastic wastage and as a result of the process a byproduct of methane will be produced. Nevertheless, this process is not much financially viable as the quantities are limited in Sri Lanka. Control of water pollution is the demand of the day cooperation of the common man, social organizations, natural government and non - governmental organizations; is required for controlling water pollution through different curative measures. -

Post-Tsunami Reconstruction Needs Assessment Northeast Planning and Development Secretariat

Post-Tsunami Reconstruction Needs Assessment for the NorthEast (NENA) Planning and Development Secretariat Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam January 2005 Contents Page 1 Introduction 1 2 Background 2 3 Overview 4 4 Needs Assessment- Sectoral Summaries 7 4.1 Resettlement 7 4.2 Housing 8 4.3 Health 11 4.4 Education 13 4.5 Roads & Bridges 15 4.6 Livelihood, Employment & Micro Finance 17 4.7 Fisheries 18 4.8 Agriculture 21 4.9 Tourism, Culture and Heritage 22 4.10 Environment 23 4.11 Water & Sanitation 25 4.12 Telecommunication 27 4.13 Power 28 4.14 Public Sector Infrastructure 29 4.15 Urban Development 29 4.16 Cooperative Movement 30 4.17 Coastal Protection 30 4.18 Local Government 32 4.19 Disaster Preparedness 33 5.0 Indicative Costs 34 Annex 1 Acronyms 35 Annex 2 Needs Assessment Team 36 Annex 3 Next to Needs 38 Post Tsunami Reconstruction – NorthEast Needs Assessment(NENA) Planning and Development Secretariat/LTTE 2 Post-Tsunami Reconstruction Needs Assessment for the NorthEast 1.0 Introduction The tsunami that struck the coast of Sri Lanka on 26th December 2004 is by far the worst natural disaster the country has experienced in living memory. The Northeast of the island took the greatest and direct impact and the full force of the fierce waves changing the lives of people and the landscape along more than 800 km of the coastline for ever. Within a few devastating minutes, tens of thousands of lives were lost, and billions of dollars worth of infrastructure, equipment and materials were shattered or washed to the seas; thousands more were wounded. -

Sri Lanka – Tamils – Eastern Province – Batticaloa – Colombo

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: LKA34481 Country: Sri Lanka Date: 11 March 2009 Keywords: Sri Lanka – Tamils – Eastern Province – Batticaloa – Colombo – International Business Systems Institute – Education system – Sri Lankan Army-Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam conflict – Risk of arrest This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide information on the International Business Systems Institute in Kaluvanchikkudy. 2. Is it likely that someone would attain a high school or higher education qualification in Sri Lanka without learning a language other than Tamil? 3. Please provide an overview/timeline of relevant events in the Eastern Province of Sri Lanka from 1986 to 2004, with particular reference to the Sri Lankan Army (SLA)-Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) conflict. 4. What is the current situation and risk of arrest for male Tamils in Batticaloa and Colombo? RESPONSE 1. Please provide information on the International Business Systems Institute in Kaluvanchikkudy. Note: Kaluvanchikkudy is also transliterated as Kaluwanchikudy is some sources. No references could be located to the International Business Systems Institute in Kaluvanchikkudy. The Education Guide Sri Lanka website maintains a list of the “Training Institutes Registered under the Ministry of Skills Development, Vocational and Tertiary Education”, and among these is ‘International Business System Overseas (Pvt) Ltd’ (IBS). -

Update UNHCR/CDR Background Paper on Sri Lanka

NATIONS UNIES UNITED NATIONS HAUT COMMISSARIAT HIGH COMMISSIONER POUR LES REFUGIES FOR REFUGEES BACKGROUND PAPER ON REFUGEES AND ASYLUM SEEKERS FROM Sri Lanka UNHCR CENTRE FOR DOCUMENTATION AND RESEARCH GENEVA, JUNE 2001 THIS INFORMATION PAPER WAS PREPARED IN THE COUNTRY RESEARCH AND ANALYSIS UNIT OF UNHCR’S CENTRE FOR DOCUMENTATION AND RESEARCH ON THE BASIS OF PUBLICLY AVAILABLE INFORMATION, ANALYSIS AND COMMENT, IN COLLABORATION WITH THE UNHCR STATISTICAL UNIT. ALL SOURCES ARE CITED. THIS PAPER IS NOT, AND DOES NOT, PURPORT TO BE, FULLY EXHAUSTIVE WITH REGARD TO CONDITIONS IN THE COUNTRY SURVEYED, OR CONCLUSIVE AS TO THE MERITS OF ANY PARTICULAR CLAIM TO REFUGEE STATUS OR ASYLUM. ISSN 1020-8410 Table of Contents LIST OF ACRONYMS.............................................................................................................................. 3 1 INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................... 4 2 MAJOR POLITICAL DEVELOPMENTS IN SRI LANKA SINCE MARCH 1999................ 7 3 LEGAL CONTEXT...................................................................................................................... 17 3.1 International Legal Context ................................................................................................. 17 3.2 National Legal Context........................................................................................................ 19 4 REVIEW OF THE HUMAN RIGHTS SITUATION............................................................... -

List of Grade Ii Officers As at 30.06.2021

LIST OF GRADE II OFFICERS AS AT 30.06.2021 * If There any corrections to be done please contact SLAS Branch. (TP 0112698605) ** We regret to inform that we are not in a position to update the details of the officers that were not sent to us after assumption of duties. Date Of Sen. Date Of File No Name Present Post Place Of Work Date Of Birth Entry To No. Promo. To II SLAS 1 75/10/3472 Mr. W.M. Gunawardane Interdicted 26-Jul-1962 16-Nov-1992 16-Nov-2002 Assistant Charity 2 75/10/4175 Ms. H.D. Thusharika Colombo Municipal Council - Western Province 7-Apr-1973 1-Sep-2003 1-Sep-2013 Commissioner 3 75/10/4574 Mr. K.G.D.C. Malraj Acting Director (Kaluthara) Department of Samurdhi Development 26-Jul-1977 2-Oct-2006 19-Jun-2017 4 75/10/4621 Mr. K.P. Kulathilake Acting Divisional Secretary Divisional Secretariat, Monaragala 7-Jun-1980 2-Oct-2006 1-Jan-2018 5 75/10/4813 Mr. B.S. Ranjitha Acting Divisional Secretary Divisional Secretariat, Hakmana 13-Jan-1964 10-Sep-2007 9-Mar-2018 6 75/10/4848 Ms. I.K.R.S. Bandara Menike Acting Divisional Secretary Divisional Secretariat, Deraniyagala 21-Feb-1967 10-Sep-2007 9-Mar-2018 7 75/10/4477 Ms. W. Warnakulasuriya Acting Divisional Secretary Divisional Secretariat, Ibbagamuwa 30-May-1972 1-Mar-2006 14-Apr-2018 Acting Senior Assistant State Ministry of Rural and Divisional Drinking Water Supply 8 75/10/4182 Mr. W.M.D.S. Gunaratne 23-Mar-1975 1-Sep-2003 27-Apr-2018 Secretary Projects Development Mr. -

Divisional Secretariats Contact Details

Divisional Secretariats Contact Details District Divisional Secretariat Divisional Secretary Assistant Divisional Secretary Life Location Telephone Mobile Code Name E-mail Address Telephone Fax Name Telephone Mobile Number Name Number 5-2 Ampara Ampara Addalaichenai [email protected] Addalaichenai 0672277336 0672279213 J Liyakath Ali 0672055336 0778512717 0672277452 Mr.MAC.Ahamed Naseel 0779805066 Ampara Ampara [email protected] Divisional Secretariat, Dammarathana Road,Indrasarapura,Ampara 0632223435 0632223004 Mr.H.S.N. De Z.Siriwardana 0632223495 0718010121 063-2222351 Vacant Vacant Ampara Sammanthurai [email protected] Sammanthurai 0672260236 0672261124 Mr. S.L.M. Hanifa 0672260236 0716829843 0672260293 Mr.MM.Aseek 0777123453 Ampara Kalmunai (South) [email protected] Divisional Secretariat, Kalmunai 0672229236 0672229380 Mr.M.M.Nazeer 0672229236 0772710361 0672224430 Vacant - Ampara Padiyathalawa [email protected] Divisional Secretariat Padiyathalawa 0632246035 0632246190 R.M.N.Wijayathunga 0632246045 0718480734 0632050856 W.Wimansa Senewirathna 0712508960 Ampara Sainthamarathu [email protected] Main Street Sainthamaruthu 0672221890 0672221890 Mr. I.M.Rikas 0752800852 0672056490 I.M Rikas 0777994493 Ampara Dehiattakandiya [email protected] Divisional Secretariat, Dehiattakandiya. 027-2250167 027-2250197 Mr.R.M.N.C.Hemakumara 027-2250177 0701287125 027-2250081 Mr.S.Partheepan 0714314324 Ampara Navithanvelly [email protected] Divisional secretariat, Navithanveli, Amparai 0672224580 0672223256 MR S.RANGANATHAN 0672223256 0776701027 0672056885 MR N.NAVANEETHARAJAH 0777065410 0718430744/0 Ampara Akkaraipattu [email protected] Main Street, Divisional Secretariat- Akkaraipattu 067 22 77 380 067 22 800 41 M.S.Mohmaed Razzan 067 2277236 765527050 - Mrs. A.K. Roshin Thaj 774659595 Ampara Ninthavur Nintavur Main Street, Nintavur 0672250036 0672250036 Mr. T.M.M. -

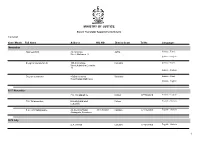

Name List of Sworn Translators in Sri Lanka

MINISTRY OF JUSTICE Sworn Translator Appointments Details 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages November Rasheed.H.M. 76,1st Cross Jaffna Sinhala - Tamil Street,Ninthavur 12 Sinhala - English Sivagnanasundaram.S. 109,4/2,Collage Colombo Sinhala - Tamil Street,Kotahena,Colombo 13 Sinhala - English Dreyton senaratna 45,Old kalmunai Baticaloa Sinhala - Tamil Road,Kalladi,Batticaloa Sinhala - English 1977 November P.M. Thilakarathne Chilaw 0777892610 Sinhala - English P.M. Thilakarathne kirimathiyana East, Chilaw English - Sinhala Lunuwilla. S.D. Cyril Sadanayake 26, De silva Road, 331490350V Kalutara 0771926906 English - Sinhala Atabagoda, Panadura 1979 July D.A. vincent Colombo 0776738956 English - Sinhala 1 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 1992 July H.M.D.A. Herath 28, Kolawatta, veyangda 391842205V Gampaha 0332233032 Sinhala - English 2000 June W.A. Somaratna 12, sanasa Square, Gampaha 0332224351 English - Sinhala Gampaha 2004 July kalaichelvi Niranjan 465/1/2, Havelock Road, Colombo English - Tamil Colombo 06 2008 May saroja indrani weeratunga 1E9 ,Jayawardanagama, colombo English - battaramulla Sinhala - 2008 September Saroja Indrani Weeratunga 1/E/9, Jayawadanagama, Colombo Sinhala - English Battaramulla 2011 July P. Maheswaran 41/B, Ammankovil Road, Kalmunai English - Sinhala Kalmunai -2 Tamil - K.O. Nanda Karunanayake 65/2, Church Road, Gampaha 0718433122 Sinhala - English Gampaha 2011 November J.D. Gunarathna "Shantha", Kalutara 0771887585 Sinhala - English Kandawatta,Mulatiyana, Agalawatta. 2 1/29/2021 Year / Month Full Name Address NIC NO District Court Tel No Languages 2012 January B.P. Eranga Nadeshani Maheshika 35, Sri madhananda 855162954V Panadura 0773188790 English - French Mawatha, Panadura 0773188790 Sinhala - 2013 Khan.C.M.S. -

Nationalism, Caste-Blindness, and the Continuing Problems of War-Displaced Panchamars in Post-War Jaffna Society

Article CASTE: A Global Journal on Social Exclusion Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 51–70 February 2020 brandeis.edu/j-caste ISSN 2639-4928 DOI: 10.26812/caste.v1i1.145 Nationalism, Caste-Blindness, and the Continuing Problems of War-Displaced Panchamars in Post-War Jaffna Society Kalinga Tudor Silva1 Abstract More than a decade after the end of the 26-year old LTTE—led civil war in Sri Lanka, a particular section of the Jaffna society continues to stay as Internally Displaced People (IDP). This paper tries to unravel why some low caste groups have failed to end their displacement and move out of the camps while everybody else has moved on to become a settled population regardless of the limitations they experience in the post-war era. Using both quantitative and qualitative data from the affected communities the paper argues that ethnic-biases and ‘caste-blindness’ of state policies, as well as Sinhala and Tamil politicians largely informed by rival nationalist perspectives are among the underlying causes of the prolonged IDP problem in the Jaffna Peninsula. In search of an appropriate solution to the intractable IDP problem, the author calls for an increased participation of these subaltern caste groups in political decision making and policy dialogues, release of land in high security zones for the affected IDPs wherever possible, and provision of adequate incentives for remaining people to move to alternative locations arranged by the state in consultation with IDPs themselves and members of neighbouring communities where they cannot be relocated at their original sites. Keywords Caste, caste-blindness, ethnicity, nationalism, social class, IDPs, Panchamars, Sri Lanka 1Department of Sociology, University of Peradeniya, Peradeniya, Sri Lanka E-mail: [email protected] © 2020 Kalinga Tudor Silva.