Sri Lanka – Tamils – Eastern Province – Batticaloa – Colombo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHAPTER 4 Perspective of the Colombo Metropolitan Area 4.1 Identification of the Colombo Metropolitan Area

Urban Transport System Development Project for Colombo Metropolitan Region and Suburbs CoMTrans UrbanTransport Master Plan Final Report CHAPTER 4 Perspective of the Colombo Metropolitan Area 4.1 Identification of the Colombo Metropolitan Area 4.1.1 Definition The Western Province is the most developed province in Sri Lanka and is where the administrative functions and economic activities are concentrated. At the same time, forestry and agricultural lands still remain, mainly in the eastern and south-eastern parts of the province. And also, there are some local urban centres which are less dependent on Colombo. These areas have less relation with the centre of Colombo. The Colombo Metropolitan Area is defined in order to analyse and assess future transport demands and formulate a master plan. For this purpose, Colombo Metropolitan Area is defined by: A) areas that are already urbanised and those to be urbanised by 2035, and B) areas that are dependent on Colombo. In an urbanised area, urban activities, which are mainly commercial and business activities, are active and it is assumed that demand for transport is high. People living in areas dependent on Colombo area assumed to travel to Colombo by some transport measures. 4.1.2 Factors to Consider for Future Urban Structures In order to identify the CMA, the following factors are considered. These factors will also define the urban structure, which is described in Section 4.3. An effective transport network will be proposed based on the urban structure as well as the traffic demand. At the same time, the new transport network proposed will affect the urban structure and lead to urban development. -

Newsletter Supporting Communities in Need

NEWSLETTER ICRC JULY-SEPTEMBER 2014 SUPPORTING COMMUNITIES IN NEED Economic security and water and sanitation for the vulnerable Dear Reader, they could reduce the immense economic This year, the ICRC started a Community Conflicts destroy livelihoods and hardships and poverty under which they Based Livelihood Support Programme infrastructure which provide water and and their families are living at present” (para (CBLSP) to support vulnerable communities sanitation to communities. Throughout 5.112). in the Mullaitivu and Kilinochchi districts the world, the ICRC strives to enable access to establish or consolidate an income to clean water and sanitation and ensure The ICRC’s response during the recovery generating activity. economic security for people affected by phase to those made vulnerable by the conflict so they can either restore or start a conflict was the piloting of a Micro Economic The ICRC’s economic security programmes livelihood. Initiatives (MEI) programme for women- are closely linked to its water and sanitation headed households, people with disabilities initiatives. In Sri Lanka today, the ICRC supports and extremely vulnerable households in vulnerable households and communities In Sri Lanka, the ICRC restores wells the Vavuniya district in 2011. The MEI is in the former conflict areas to become contaminated as a result of monsoonal a programme in which each beneficiary economically independent through flooding, and renovates and builds pipe identifies and designs the livelihood sustainable income generation activities and networks, overhead water tanks, and for which he or she needs assistance to provides them clean water and sanitation by toilets in rural communities for returnee implement, thereby employing a bottom- cleaning wells and repairing or constructing populations to have access to clean water up needs-based approach. -

Beautification and the Embodiment of Authenticity in Post-War Eastern Sri Lanka

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Undergraduate Humanities Forum 2014-2015: Penn Humanities Forum Undergraduate Color Research Fellows 5-2015 Ornamenting Fingernails and Roads: Beautification and the Embodiment of Authenticity in Post-War Eastern Sri Lanka Kimberly Kolor University of Pennsylvania Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/uhf_2015 Part of the Asian History Commons Kolor, Kimberly, "Ornamenting Fingernails and Roads: Beautification and the Embodiment of uthenticityA in Post-War Eastern Sri Lanka" (2015). Undergraduate Humanities Forum 2014-2015: Color. 7. https://repository.upenn.edu/uhf_2015/7 This paper was part of the 2014-2015 Penn Humanities Forum on Color. Find out more at http://www.phf.upenn.edu/annual-topics/color. This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/uhf_2015/7 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ornamenting Fingernails and Roads: Beautification and the Embodiment of Authenticity in Post-War Eastern Sri Lanka Abstract In post-conflict Sri Lanka, communal tensions continue ot be negotiated, contested, and remade. Color codes virtually every aspect of daily life in salient local idioms. Scholars rarely focus on the lived visual semiotics of local, everyday exchanges from how women ornament their nails to how communities beautify their open—and sometimes contested—spaces. I draw on my ethnographic data from Eastern Sri Lanka and explore ‘color’ as negotiated through personal and public ornaments and notions of beauty with a material culture focus. I argue for a broad view of ‘public,’ which includes often marginalized and feminized public modalities. This view also explores how beauty and ornament are salient technologies of community and cultural authenticity that build on histories of ethnic imaginaries. -

CHAP 9 Sri Lanka

79o 00' 79o 30' 80o 00' 80o 30' 81o 00' 81o 30' 82o 00' Kankesanturai Point Pedro A I Karaitivu I. Jana D Peninsula N Kayts Jana SRI LANKA I Palk Strait National capital Ja na Elephant Pass Punkudutivu I. Lag Provincial capital oon Devipattinam Delft I. Town, village Palk Bay Kilinochchi Provincial boundary - Puthukkudiyiruppu Nanthi Kadal Main road Rameswaram Iranaitivu Is. Mullaittivu Secondary road Pamban I. Ferry Vellankulam Dhanushkodi Talaimannar Manjulam Nayaru Lagoon Railroad A da m' Airport s Bridge NORTHERN Nedunkeni 9o 00' Kokkilai Lagoon Mannar I. Mannar Puliyankulam Pulmoddai Madhu Road Bay of Bengal Gulf of Mannar Silavatturai Vavuniya Nilaveli Pankulam Kebitigollewa Trincomalee Horuwupotana r Bay Medawachchiya diya A d o o o 8 30' ru 8 30' v K i A Karaitivu I. ru Hamillewa n a Mutur Y Pomparippu Anuradhapura Kantalai n o NORTH CENTRAL Kalpitiya o g Maragahewa a Kathiraveli L Kal m a Oy a a l a t t Puttalam Kekirawa Habarane u 8o 00' P Galgamuwa 8o 00' NORTH Polonnaruwa Dambula Valachchenai Anamaduwa a y O Mundal Maho a Chenkaladi Lake r u WESTERN d Batticaloa Naula a M uru ed D Ganewatta a EASTERN g n Madura Oya a G Reservoir Chilaw i l Maha Oya o Kurunegala e o 7 30' w 7 30' Matale a Paddiruppu h Kuliyapitiya a CENTRAL M Kehelula Kalmunai Pannala Kandy Mahiyangana Uhana Randenigale ya Amparai a O a Mah Reservoir y Negombo Kegalla O Gal Tirrukkovil Negombo Victoria Falls Reservoir Bibile Senanayake Lagoon Gampaha Samudra Ja-Ela o a Nuwara Badulla o 7 00' ng 7 00' Kelan a Avissawella Eliya Colombo i G Sri Jayewardenepura -

Update UNHCR/CDR Background Paper on Sri Lanka

NATIONS UNIES UNITED NATIONS HAUT COMMISSARIAT HIGH COMMISSIONER POUR LES REFUGIES FOR REFUGEES BACKGROUND PAPER ON REFUGEES AND ASYLUM SEEKERS FROM Sri Lanka UNHCR CENTRE FOR DOCUMENTATION AND RESEARCH GENEVA, JUNE 2001 THIS INFORMATION PAPER WAS PREPARED IN THE COUNTRY RESEARCH AND ANALYSIS UNIT OF UNHCR’S CENTRE FOR DOCUMENTATION AND RESEARCH ON THE BASIS OF PUBLICLY AVAILABLE INFORMATION, ANALYSIS AND COMMENT, IN COLLABORATION WITH THE UNHCR STATISTICAL UNIT. ALL SOURCES ARE CITED. THIS PAPER IS NOT, AND DOES NOT, PURPORT TO BE, FULLY EXHAUSTIVE WITH REGARD TO CONDITIONS IN THE COUNTRY SURVEYED, OR CONCLUSIVE AS TO THE MERITS OF ANY PARTICULAR CLAIM TO REFUGEE STATUS OR ASYLUM. ISSN 1020-8410 Table of Contents LIST OF ACRONYMS.............................................................................................................................. 3 1 INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................................... 4 2 MAJOR POLITICAL DEVELOPMENTS IN SRI LANKA SINCE MARCH 1999................ 7 3 LEGAL CONTEXT...................................................................................................................... 17 3.1 International Legal Context ................................................................................................. 17 3.2 National Legal Context........................................................................................................ 19 4 REVIEW OF THE HUMAN RIGHTS SITUATION............................................................... -

UN-Habitat Implements Disaster Risk Reduction Initiatives in Mannar Town in Sri Lanka's Northern Province

UN‐Habitat Implements Disaster Risk Reduction Initiatives in Mannar Town in Sri Lanka’s Northern Province May 2014, Mannar, Sri Lanka. The United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN‐Habitat), in collaboration with the Mannar Urban Council, is implementing a number of small scale Disaster Risk Reduction (DRR) initiatives to assist communities cope with the adverse impacts of natural disasters through the Disaster Resilient City Development Strategies for four Cities in the Northern and Eastern Provinces of Sri Lanka (Phase II) Project. Funded by the Government of Australia, the project is being implemented by UN‐Habitat in the towns of Mannar, Vavuniya, Mullaitivu and Akkaraipattu in collaboration with the Local Authorities, the Ministry of Disaster Management, and Urban Development Authority (UDA), Sri Lanka Institute of Local Governance (SLILG), Institute for Construction Training and Development (ICTAD) and the University of Moratuwa. Implementing small scale DRR interventions is a key output of the Disaster Resilient Urban Planning and Development Unit that has been established at the Mannar Urban Council. The need for such DRR activities was identified by the project partners as a key priority during the implementation of Phase I during 2012‐2013. As a result, additional funding has been allocated to implement small scale DRR activities in the four cities during the second phase. Small scale infrastructure has been identified by the communities and the LAs to reduce the vulnerability to disasters of settlements and communities. In the Mannar Urban Council area, the infrastructure activities 50 Housing Scheme Road before rehabilitation identified included rehabilitation of two internal roads and laying of Hume pipes and culverts to release storm water from flood‐prone areas. -

Batticaloa District

LAND USE PLAN BATTICALOA DISTRICT 2016 Land Use Policy Planning Department No.31 Pathiba Road, Colombo 05. Tel.0112 500338,Fax: 0112368718 1 E-mail: [email protected] Secretary’s Message Lessons Learnt and Reconciliation Commission (LLRC) made several recommendations for the Northern and Eastern Provinces of Sri Lanka so as to address the issues faced by the people in those areas due to the civil war. The responsibility of implementing some of these recommendations was assigned to the different institutions coming under the purview of the Ministry of Lands i.e. Land Commissioner General Department, Land Settlement Department, Survey General Department and Land Use Policy Planning Department. One of The recommendations made by the LLRC was to prepare Land Use Plans for the Districts in the Northern and Eastern Provinces. This responsibility assigned to the Land Use Policy Planning Department. The task was completed by May 2016. I would like to thank all the National Level Experts, District Secretary and Divisional Secretaries in Batticaloa District and Assistant Director (District Land Use.). Batticaloa and the district staff who assisted in preparing this plan. I also would like to thank Director General of the Land Use Policy Planning Department and the staff at the Head Office their continuous guiding given to complete this important task. I have great pleasure in presenting the Land Use Plan for the Batticaloa district. Dr. I.H.K. Mahanama Secretary, Ministry of Lands 2 Director General’s Message I have great pleasure in presenting the Land Use Plan for the Batticaloa District prepared by the officers of the Land Use Policy Planning Department. -

Divisional Secretariats Contact Details

Divisional Secretariats Contact Details District Divisional Secretariat Divisional Secretary Assistant Divisional Secretary Life Location Telephone Mobile Code Name E-mail Address Telephone Fax Name Telephone Mobile Number Name Number 5-2 Ampara Ampara Addalaichenai [email protected] Addalaichenai 0672277336 0672279213 J Liyakath Ali 0672055336 0778512717 0672277452 Mr.MAC.Ahamed Naseel 0779805066 Ampara Ampara [email protected] Divisional Secretariat, Dammarathana Road,Indrasarapura,Ampara 0632223435 0632223004 Mr.H.S.N. De Z.Siriwardana 0632223495 0718010121 063-2222351 Vacant Vacant Ampara Sammanthurai [email protected] Sammanthurai 0672260236 0672261124 Mr. S.L.M. Hanifa 0672260236 0716829843 0672260293 Mr.MM.Aseek 0777123453 Ampara Kalmunai (South) [email protected] Divisional Secretariat, Kalmunai 0672229236 0672229380 Mr.M.M.Nazeer 0672229236 0772710361 0672224430 Vacant - Ampara Padiyathalawa [email protected] Divisional Secretariat Padiyathalawa 0632246035 0632246190 R.M.N.Wijayathunga 0632246045 0718480734 0632050856 W.Wimansa Senewirathna 0712508960 Ampara Sainthamarathu [email protected] Main Street Sainthamaruthu 0672221890 0672221890 Mr. I.M.Rikas 0752800852 0672056490 I.M Rikas 0777994493 Ampara Dehiattakandiya [email protected] Divisional Secretariat, Dehiattakandiya. 027-2250167 027-2250197 Mr.R.M.N.C.Hemakumara 027-2250177 0701287125 027-2250081 Mr.S.Partheepan 0714314324 Ampara Navithanvelly [email protected] Divisional secretariat, Navithanveli, Amparai 0672224580 0672223256 MR S.RANGANATHAN 0672223256 0776701027 0672056885 MR N.NAVANEETHARAJAH 0777065410 0718430744/0 Ampara Akkaraipattu [email protected] Main Street, Divisional Secretariat- Akkaraipattu 067 22 77 380 067 22 800 41 M.S.Mohmaed Razzan 067 2277236 765527050 - Mrs. A.K. Roshin Thaj 774659595 Ampara Ninthavur Nintavur Main Street, Nintavur 0672250036 0672250036 Mr. T.M.M. -

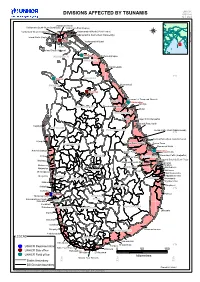

DIVISIONS AFFECTED by TSUNAMIS GIS Unit Sri Lanka

UNHCR DIVISIONS AFFECTED BY TSUNAMIS GIS Unit Sri Lanka ValikamamValikamam NorthNorth ValikamamValikamam South-WestSouth-West (Sandilipay)(Sandilipay) ValikamamValikamam EastEast (Kopay)(Kopay) Valikamam West (Chankanai) VadamaradchiVadamaradchi NorthNorth (Point(Point Perdro)Perdro) JAFFNAJAFFNA VadamaradchiVadamaradchi South-WestSouth-West (Karaveddy)(Karaveddy) Island North (Kayts) JaffnaJaffna VadamaradchiVadamaradchi EastEast Divisions.WOR Affected Jaffna DelftDelft DelftDelftIsland South (Velanai) KillinochchiKillinochchi KILINOCHCHIKILINOCHCHI KillinochchiKillinochchi PuthukudiyiruppuPuthukudiyiruppu MULLAITIVUMULLAITIVU MaritimepattuMaritimepattu 9°N MannarMannar VAVUNIYAVAVUNIYA MANNARMANNAR KuchchaveliKuchchaveli VavuniyaVavuniya TrincomaleeTrincomalee TownTown andand GravetsGravets MorawewaMorawewa TrincomaleeTrincomalee KinniyaKinniya ANURADHAPURAANURADHAPURA ThambalagamuwaThambalagamuwa MutturMuttur TRINCOMALEETRINCOMALEE SeruvilaSeruvila Verugal/Verugal/ EchchilampattaiEchchilampattai KoralaiKoralai PattuPattu NorthNorth KalpitiyaKalpitiya PUTTALAMPUTTALAM POLONNARUWAPOLONNARUWA KoralaiKoralai PattuPattu WestWest (Oddamavadi)(Oddamavadi) 8°N KoralaiKoralai PattuPattu WestWest (Valachchenai)(Valachchenai) MundelMundel KoralaiKoralai PattuPattu (South)(South) EravurEravur TownTown KURUNEGALAKURUNEGALA KoralaiKoralai PattuPattu (South)(South) EravurEravur TownTown ManmunaiManmunai NorthNorth ArachchikattuwaArachchikattuwa BatticaloaBatticaloa EravurEravur PattuPattu BatticaloaBatticaloaKattankudyKattankudy ManmunaiManmunai -

Sri Lanka Date: 19 September 2008

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: LKA33744 Country: Sri Lanka Date: 19 September 2008 Keywords: Sri Lanka – Freedom of movement – Checkpoints This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Can you please provide information on the ease with which people could travel in the east and north of Sri Lanka during 2002, and also in subsequent years until 2006? 2. Please include any information about check points. RESPONSE 1. Can you please provide information on the ease with which people could travel in the east and north of Sri Lanka during 2002, and also in subsequent years until 2006? 2. Please include any information about check points. Sources indicate that travel to the north and east of Sri Lanka was possible between 2002 and 2006 due to the signing of the peace agreement between the Sri Lankan Army (SLA) and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Elam (LTTE) in 2002. This agreement, whilst not adhered to by either party, at least reduced full scale military activity in then LTTE-held areas, -

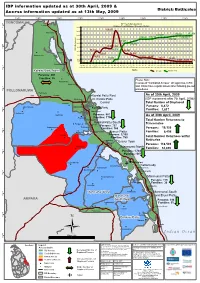

IDP Numbers and Access 30042009 GA Figures

IDP information updated as at 30th April, 2009 & District: Batticaloa Access information updated as at 13th May, 2009 81°15'0"E 81°20'0"E 81°25'0"E 81°30'0"E 81°35'0"E 81°40'0"E 81°45'0"E 81°50'0"E 81°55'0"E TRINCOMALEE (! IDP Trend - Batticaloa District Verugal Returnees Trend - Batticaloa / Trincomalee Districts 8°15'0"N 180,000 159,355 (! 160,000 Kathiravely 136,084 137,659 140,000 127,837 119,527 120,742 136,555 120,000 132,728 97,405 100,000 108,784 72,986 80,000 81,312 8°10'0"N IDPs/Returnees 60,272 68,971 60,000 51,901 (! Vaharai (! 52,685 38,230 Kaddumurivu 40,000 38,121 26,484 24,987 17,600 18,171 12,551 20,000 8,020 1,140 8,543 6,872 (! 0 Panichankerny Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr May June July Aug Sept Oct Nov Dec Jan Feb Mar Apr 2006 2006 2006 2006 2006 2006 2006 2006 2006 2007 2007 2007 2007 2007 2007 2007 2007 2007 2007 2007 2007 2008 2008 2008 2008 2008 2008 2008 2008 2008 2008 2008 2008 2009 2009 2009 2009 8°5'0"N Months IDP Trend Returnees' Trend Koralai Pattu North A 1 Persons: 201 5 Families: 55 (! Please Note: Kirimichchai In areas of "Controlled Access" UN agencies, ICRC Mankerny (! and INGO have regular access after following pre-set procedures. -

Integrated Strategic Environmental Assessment of the Northern Province of Sri Lanka Report

Integrated Strategic Environmental Assessment of the Northern Province of Sri Lanka A multi-agency approach coordinated by Central Environment Authority and Disaster Management Centre, Supported by United Nations Development Programme and United Nations Environment Programme Integrated Strategic Environmental Assessment of the Northern Province of Sri Lanka November 2014 A Multi-agency approach coordinated by the Central Environmental Authority (CEA) of the Ministry of Environment and Renewable Energy and Disaster Management Centre (DMC) of the Ministry of Disaster Management, supported by United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) Integrated Strategic Environment Assessment of the Northern Province of Sri Lanka ISBN number: 978-955-9012-55-9 First edition: November 2014 © Editors: Dr. Ananda Mallawatantri Prof. Buddhi Marambe Dr. Connor Skehan Published by: Central Environment Authority 104, Parisara Piyasa, Battaramulla Sri Lanka Disaster Management Centre No 2, Vidya Mawatha, Colombo 7 Sri Lanka Related publication: Map Atlas: ISEA-North ii Message from the Hon. Minister of Environment and Renewable Energy Strategic Environmental Assessment (SEA) is a systematic decision support process, aiming to ensure that due consideration is given to environmental and other sustainability aspects during the development of plans, policies and programmes. SEA is widely used in many countries as an aid to strategic decision making. In May 2006, the Cabinet of Ministers approved a Cabinet of Memorandum