A History and Description of Mediaeval Art Work in Copper, Brass And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Antiphonary of Bangor and Its Musical Implications

The Antiphonary of Bangor and its Musical Implications by Helen Patterson A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Music University of Toronto © Copyright by Helen Patterson 2013 The Antiphonary of Bangor and its Musical Implications Helen Patterson Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Music University of Toronto 2013 Abstract This dissertation examines the hymns of the Antiphonary of Bangor (AB) (Antiphonarium Benchorense, Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana C. 5 inf.) and considers its musical implications in medieval Ireland. Neither an antiphonary in the true sense, with chants and verses for the Office, nor a book with the complete texts for the liturgy, the AB is a unique Irish manuscript. Dated from the late seventh-century, the AB is a collection of Latin hymns, prayers and texts attributed to the monastic community of Bangor in Northern Ireland. Given the scarcity of information pertaining to music in early Ireland, the AB is invaluable for its literary insights. Studied by liturgical, medieval, and Celtic scholars, and acknowledged as one of the few surviving sources of the Irish church, the manuscript reflects the influence of the wider Christian world. The hymns in particular show that this form of poetical expression was significant in early Christian Ireland and have made a contribution to the corpus of Latin literature. Prompted by an earlier hypothesis that the AB was a type of choirbook, the chapters move from these texts to consider the monastery of Bangor and the cultural context from which the manuscript emerges. As the Irish peregrini are known to have had an impact on the continent, and the AB was recovered in ii Bobbio, Italy, it is important to recognize the hymns not only in terms of monastic development, but what they reveal about music. -

Quality Silversmiths Since 1939. SPAIN

Quality Silversmiths since 1939. SPAIN www.molina-spain.com - ARTIMETAL - PROCESSIONALIA 2014-2015 Quality Silversmiths since 1939. SPAIN ARTISTIC SILVER INDEXINDEX Presentation ......................................................................................... Pag. 1-12 ARTISTIC SILVER - ARTIMETAL ARTISTICPresentation SILVER & ARTIMETAL Pag. 1-12 ChalicesChalices && CiboriaCiboria ........................................................................... Pag. 13-6713-52 MonstrancesCruet Sets & Ostensoria ...................................................... Pag. 68-7853 TabernaclesJug & Basin,........................................................................................... Buckets Pag. 79-9654 AltarMonstrances accessories & Ostensoria Pag. 55-63 &Professional Bishop’s appointments Crosses ......................................................... Pag. 97-12264 Tabernacles Pag. 65-80 PROCESIONALIAAltar accessories ............................................................................. Pag. 123-128 & Bishop’s appointments Pag. 81-99 General Information ...................................................................... Pag. 129-132 ARTIMETAL Chalices & Ciboria Pag. 101-115 Monstrances Pag. 116-117 Tabernacles Pag. 118-119 Altar accessories Pag. 120-124 PROCESIONALIA Pag. 125-130 General Information Pag. 131-134 Quality Silversmiths since 1939. SPAIN www.molina-spain.com Luis Molina Acedo, S.A. Justo Dorado, 12 28040 Madrid, Spain Product design: Luis Molina Acedo, S.A. CHALICES & CIBORIA Our silversmiths combine -

ABOUT the Middle of the Thirteenth Century the Dean and Chapter of St

XIII.—Visitations of certain Churches in the City of London in the patronage of St. Paul's Cathedral Church, between the years 1138 and 1250. By W. SPARROW SIMPSON, D.D., Sub-Dean and Librarian of St. Paul's. Read January 16, 1896. ABOUT the middle of the thirteenth century the Dean and Chapter of St. Paul's Cathedral Church made a minute and careful visitation of churches in their gift, lying in the counties of Essex, Hertfordshire, and Middlesex. The text of that visitation has been lately printed in a volume issued by the Camden Society.'1 The record of their proceedings is so copious that a clear and distinct account can be given of the ornaments, vestments, books, and plate belonging to these churches; and some insight can be gained into the relations which existed between the parishioners, the patrons, and the parish priest. The visitations now for the first time printed are not so full and ample as could be desired. But so little authentic information is to be gathered about the furniture and ornaments of churches in the city of London at this very early period, that even these brief records may be acceptable to antiquaries. The manuscript from which these inventories have been transcribed is one of very high importance. Mr. Maxwell Lyte describes it as " a fine volume, of which the earlier part was written in the middle of the twelfth century," and he devotes about eighteen columns of closely-printed matter to a calendar of its contents illustrated by very numerous extracts." The book is known as Liber L, and the most important portions of it are now in print. -

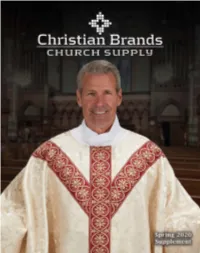

Cbcs Spring 20.Pdf

TM Dear Friends, We are pleased to introduce the 2020 Church Supply Spring Sudbury Brass™, the oldest church sanctuary furnishing firm Supplement Catalog. Please use this in addition to our annual in the United States, has added new products across most 2019-2020 Church Supply Catalog for all of your ordering needs. product lines in addition to all your favorite classic Sudbury offerings on pages 45-51. Be sure to check out our newest This spring, we’ve added nearly 200 new products from your 10-minute prayer candles from Will & Baumer® and specially ™ ™ favorite brands; R.J. Toomey , Cambridge , Celebration designed candle holder. The candle holder fits into existing ™ ® ® ™ Banners , Robert Smith , Will & Baumer and Sudbury Brass . votive glass and holds the 10 minute prayer candle upright and burns clean leaving no mess to cleanup. R.J. Toomey™, the industry leader in clergy vestments and accessories, is pleased to announce additions to the customer As always, thank you for making Christian Brands™ a partner favorite Coronation and Avignon collections, as well as the in your business. If there is anything we can do to help, first introduction of the new Monreale Collection. Choose from please feel free to contact us anytime. dozens of new chasubles, dalmatics, stoles, albs, surplices, paraments, mass linens and so much more. See pages 4-15 for Best regards, the complete R.J. Toomey™ selection of new offerings. Celebration Banners™ has quickly become the industry leader in high quality worship banners for all occasions. This season Chris Vallely [email protected] we are excited to introduce our new Sacred Image Retractable Banners, as well as a new mix of modern and traditional designs in the best-selling banner sizes and styles. -

Places of Prayer in the Monastery of Batalha Places of Prayer in the Monastery of Batalha 2 Places of Prayer in the Monastery of Batalha

PLACES OF PRAYER IN THE MONASTERY OF BATALHA PLACES OF PRAYER IN THE MONASTERY OF BATALHA 2 PLACES OF PRAYER IN THE MONASTERY OF BATALHA CONTENTS 5 Introduction 9 I. The old Convent of São Domingos da Batalha 9 I.1. The building and its grounds 17 I. 2. The keeping and marking of time 21 II. Cloistered life 21 II.1. The conventual community and daily life 23 II.2. Prayer and preaching: devotion and study in a male Dominican community 25 II.3. Liturgical chant 29 III. The first church: Santa Maria-a-Velha 33 IV. On the temple’s threshold: imagery of the sacred 37 V. Dominican devotion and spirituality 41 VI. The church 42 VI.1. The high chapel 46 VI.1.1. Wood carvings 49 VI.1.2. Sculptures 50 VI.2. The side chapels 54 VI.2.1. Wood carvings 56 VI.3. The altar of Jesus Abbreviations of the authors’ names 67 VII. The sacristy APA – Ana Paula Abrantes 68 VII.1. Wood carvings and furniture BFT – Begoña Farré Torras 71 VIII. The cloister, chapter, refectory, dormitories and the retreat at Várzea HN – Hermínio Nunes 77 IX. The Mass for the Dead MJPC – Maria João Pereira Coutinho MP – Milton Pacheco 79 IX.1. The Founder‘s Chapel PR – Pedro Redol 83 IX.2. Proceeds from the chapels and the administering of worship RQ – Rita Quina 87 X. Popular Devotion: St. Antão, the infante Fernando and King João II RS – Rita Seco 93 Catalogue SAG – Saul António Gomes SF – Sílvia Ferreira 143 Bibliography SRCV – Sandra Renata Carreira Vieira 149 Credits INTRODUCTION 5 INTRODUCTION The Monastery of Santa Maria da Vitória, a veritable opus maius in the dark years of the First Republic, and more precisely in 1921, of artistic patronage during the first generations of the Avis dynasty, made peace, through the transfer of the remains of the unknown deserved the constant praise it was afforded year after year, century soldiers killed in the Great War of 1914-1918 to its chapter room, after century, by the generations who built it and by those who with their history and homeland. -

English Ground Floor

English Ground floor Romanesque art [Artistic style] The Romanesque is a style of art that was produced in West- ern Europe’s feudal kingdoms in the Middle Ages from about the end of the 10th century to the opening decades of the 13th century. It is an artistic style with a common aesthetic language that was to be found throughout Christian Europe and beyond, from Cape Finisterre to the Holy Land and from Scandinavia to the Mediterranean. Indeed, the Romanesque was one of the first international art styles. 1st floor Art, architecture and painting Our little country, Andorra, has preserved a number of iso- lated Romanesque churches which are scattered through- out our territory. These structures are dominated by a little semicircular apse that is oriented to the east (with a few exceptions), symbolically pointing to the rising sun. The apse is where the altar is located, making it the focal point of worship in the church. A triumphal arch separates the apse –as the place reserved for God– from the nave, which is the place for the faithful. These churches have an austere appearance and a great simplicity, standing out for the uniformity of their masonry walls built with usually unhewn local stone set in lime mortar. The walls are decorated with Lombard bands, formed by simple blind arcades on the exterior of the building beneath the roof, as at Sant Miquel d’Engolasters, combining with saw-toothed friezes as at Sant Esteve d’Andorra la Vella, or lesenes (also known as pilaster strips) on the apse, as at Sant Romà de les Bons, and on the bell tower, as at Santa Colo- ma, Sant Joan de Caselles, Santa Eulàlia d’Encamp. -

Some Anomalies 1N English Candlestick Design by W C

PpoLL }dtJ 135 1 Some Anomalies 1n English Candlestick Design BY W C. MACKAY THOMAS N the latter half of the XVth century the simple Encircling the base of this candlestick is an inscription English candlestick was eclipsed by the introduction which reads, "In ye begynnyng God be my," and has I of a Venetian model which the Venetians in turn been interpreted, "In the beginning God made me," had copied from the Near East, and it became very and by the style of lettering and the mode of spelling popular on account of its appeal to the bell-founders, the authorities pronounce it of XVlth century origin. for the profile of their smaller bells could be utilised Being fashioned in brass at a period prior to its in the formation of the base. The sketch in Fig. I manufacture in this country, it must have been con shows such an example made of bell-metal in the reign structed from foreign metal and at a time when a great of Henry VI and is now in the writer's collection. quantity had been thrown .on the market by the melting Before proceeding further it is essential to under down of church brasses. Starting with the Dissolution stand why a city so far removed from this country of Monasteries, the practice became so remunerative that should have so dominant an influence. As. in this brief the custom of despoiling the churches on the slightest article, it would be impossible to treat fully the cause of pretext by tearing the brass tablets from their stone this close association between Venice and England, a matrices was all too prevalent even in Elizabethan times, few salient facts must suffice. -

Manufacturers & Importers of Fine Church Goods

Essential Church Products 2017-2018 Manufacturers & Importers of Fine Church Goods INDEX INDEX INDEX INDEX INDEX INDEX Index A O Ablution Cup .......................... .41 Cruet Brush ........................... .45 Oil Stocks ........................ 30,41,42 Advent Wreath ......................... 2,3 Cruet Drainer .......................... .45 Bishops’ ........................... .42 Altar Cloth Fasteners .................... .47 Cruet Set ............................. .45 Ceremonial ......................... 30 Ambry/Holy Oil Safe ..................... 41 Processional ........................ 45 Offering Box ........................... 48 Ambry Set ............................ .41 Cruet Spoon ........................... 45 Ostensorium ...................... .9,10,11 Ash Holder ............................ 41 Crystal Asterisk .............................. .47 Ambry Set ......................... .41 P Chalice, Cruets, Flagon, Paten ........ 44,45 Pastoral Set ......................... 30,31 B Miscellaneous Items ................ 41,44 Paten ......................... 32,36,38,39 Bags for Sacred Vessels ................. .47 Cup Carrier ............................ 39 Bowl ......................... 38,39,44 Banner Stands ........................ 5,48 Communion ........................ .38 Baptismal Bowl ........................ .40 D Credence .......................... .47 Baptismal Cover ........................ 40 Deacon’s Set .......................... .31 Well-type .......................... .38 Baptismal Set ......................... -

Censer Stands Sprinkler Included Items Shown on Censer Stands Not Included

Essential Church Products 2018-2019 orters of Imp Fin s & e C er hu ur r t ch c fa G u o n o a d s M 800-243-6385 INDEX INDEX INDEX INDEX INDEX INDEX Index A O Ablution Cup .......................... .41 Cruet Brush ........................... .45 Oil Stocks ........................ 30,41,42 Advent Wreath ......................... 2,3 Cruet Drainer .......................... .45 Bishops’ ........................... .42 Altar Cloth Fasteners .................... .47 Cruet Set ............................. .45 Ceremonial ......................... 30 Ambry/Holy Oil Safe ..................... 41 Processional ........................ 45 Offering Box ........................... 48 Ambry Set ............................ .41 Cruet Spoon ........................... 45 Ostensorium ...................... .9,10,11 Ash Holder ............................ 41 Crystal Asterisk .............................. .47 Ambry Set ......................... .41 P Chalice, Cruets, Flagon, Paten ........ 44,45 Pastoral Set ......................... 30,31 B Miscellaneous Items ................ 41,44 Paten ......................... 32,36,38,39 Bags for Sacred Vessels ................. .47 Cup Carrier ............................ 39 Bowl ......................... 38,39,44 Banner Stands ........................ 5,48 Communion ........................ .38 Baptismal Bowl ........................ .40 D Credence .......................... .47 Baptismal Cover ........................ 40 Deacon’s Set .......................... .31 Well-type .......................... .38 Baptismal -

What Is the Roman Missal My Account | Register | Help

What Is The Roman Missal My Account | Register | Help My Dashboard Get Published Home Books Search Support About Get Published Us Most Popular New Releases Top Picks eBook Finder... SEARCH R O M A N M I S S A L Article Id: WHEBN0000025878 Reproduction Date: Title: Roman Missal Author: World Heritage Encyclopedia Language: English Subject: Latin liturgical rites, Canon of the Mass, Ad orientem, Embolism (liturgy), Nicene Creed Catholic Liturgical Books, Christian Terminology, Eucharist, Mass (Liturgy), Missals, Collection: Tridentine Mass Publisher: World Heritage Encyclopedia Publication Date: Flag as Inappropriate Email this Article ROMAN MISSAL The Roman Missal (Latin: Missale Romanum) is the liturgical book that contains the texts and rubrics for the celebration of the Mass in the Roman Rite of the Catholic Church. HISTORY CONTENTS History 1 Situation before the Council of Trent 1.1 From the Council of Trent to the Second Vatican Council 1.2 Revision of the Missal following the Second Vatican Council 1.3 More recent changes 1.4 Continued use of earlier editions 1.5 Official English translations 2 See also 3 Further reading 4 References 5 Online texts of editions of the Roman Missal 6 Full texts of the Missale Romanum 6.1 Texts of Roman Rite missals earlier than the 1570 Roman Missal 6.2 The 2011 English translation 6.3 Partial texts 6.4 SITUATION BEFORE THE COUNCIL OF TRENT Before the high Middle Ages, several books were used at Mass: a Sacramentary with the prayers, one or more books for the Scriptural readings, and one or more books for the antiphons and other chants. -

Victorian Heritage Database Place Details - 27/9/2021 ST KILIANS CATHOLIC CHURCH

Victorian Heritage Database place details - 27/9/2021 ST KILIANS CATHOLIC CHURCH Location: 173 MCCRAE STREET BENDIGO, GREATER BENDIGO CITY Victorian Heritage Register (VHR) Number: H1341 Listing Authority: VHR Extent of Registration: 1. All the building including the German organ marked B1; iron and granite fence to Chapel and McCrae Streets, and the iron fence surrounding Dr Backhaus' grave marked B2; Dr Backhaus' grave marked B3; bell- tower and bell marked B4; on Diagram 600048 held by the Executive Director. 2. All the land marked L1 on Diagram 600048, held by the Executive Director, being part of the land described in Certificate of Title Vol 1038 Folio 537, City and Parish of Sandhurst, County of Bendigo. 3. All the specified movable objects: marble and granite baptismal font; 56 curve-ended pews; organ bench seat; Dr Backhaus' stump chair; small nave table; high altar and reredos; high altar side table; the altar; altar candlestick; the sedile; two side altars; two side altar tables. 4. All the Washingtonia robusta (Washington palms); the Phoenix canariensis (Canary Island palms); and the Trachycarpus fortunei (Chinese windmill palm); marked T1, T2 and T3 respectively on Diagram 600048, held by the Executive Director. Statement of Significance: Within months of gold being discovered in Bendigo in 1851, the Rev Father Dr Henry Backhaus (1811-1882) arrived on the diggings and celebrated the first 1 mass. For over a year he conducted services in a tent, before a bark and slab chapel was built for him by the diggers. The first St Kilian's church was constructed in 1857. -

February 14/15, 2021 the Transfiguration of Our Lord

February 14/15, 2021 The Transfiguration of our Lord Redeemer Lutheran Church and 3K/4K Preschool 1712 Menasha Ave. Manitowoc, Wisconsin (920) 684-3989 www.redeemermanty.com Welcome I was glad when they said to me, “Let us go to the house of the LORD!” Psalm 122:1 Please maintain proper distancing. When we distribute Holy Communion the entire Pulpit/right side of the sanctuary will be communed followed then by the left side of the church. DO NOT fill out a Communion card. For the time being we will practice “Continuous Communion.” What that means is that while we will still line up down the main aisle one person at a time will take Communion. You will receive the host and then receive the cup. After that you will return to your seat as normal. Through all of this we remember, especially when we gather for worship: This is the day that the LORD has made; let us rejoice and be glad in it! Psalm 118:24 Prayer Before Worship O Lord, my creator, redeemer, and comforter, as I come to worship You in spirit and in truth, I humbly pray that You would open my heart to the preaching of Your Word so that I may repent of my sins, believe in Jesus Christ as my only Savior, and grow in grace and holiness. Hear me for the sake of His name. Amen. Prayer Before Communing Dear Savior, at Your gracious invitation I come to Your table to eat and drink Your holy body and blood. Let me find favor in Your eyes to receive this holy Sacrament in faith for the salvation of my soul and to the glory of Your holy name; for You live and reign with the Father and the Holy Spirit, one God, now and forever.