Submandibular Space Infection: a Potentially Lethal Infection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Anatomical Overview

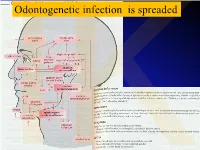

IKOdontogenetic infection is spreaded Možné projevy zlomenin a zánětů IKPossible signs of fractures or inflammations Submandibular space lies between the bellies of the digastric muscles, mandible, mylohyoid muscle and hyoglossus and styloglossus muscles IK IK IK IK IK Submandibulární absces Submandibular abscess IK Sběhlý submandibulární absces Submandibular abscess is getting down IK Submental space lies between the mylohyoid muscles and the investing layer of deep cervical fascia superficially IK IK Spatium peritonsillare IK IK Absces v peritonsilární krajině Abscess in peritonsilar region IK Fasciae Neck fasciae cervicales Demarcate spaces • fasciae – Superficial (investing): • f. nuchae, f. pectoralis, f. deltoidea • invests m. sternocleidomastoideus + trapezius • f. supra/infrahyoidea – pretrachealis (middle neck f.) • form Δ, invests infrahyoid mm. • vagina carotica (carotic sheet) – Prevertebral (deep cervical f.) • Covers scaleni mm. IK• Alar fascia Fascie Fascia cervicalis superficialis cervicales Fascia cervicalis media Fascia cervicalis profunda prevertebralis IKsuperficialis pretrachealis Neck spaces - extent • paravisceral space – Continuation of parafaryngeal space – Nervous and vascular neck bundle • retrovisceral space – Between oesophagus and prevertebral f. – Previsceral space – mezi l. pretrachealis a orgány – v. thyroidea inf./plx. thyroideus impar • Suprasternal space – Between spf. F. and pretracheal one IK– arcus venosus juguli 1 – sp. suprasternale suprasternal Spatia colli 2 – sp. pretracheale pretracheal 3 – -

ODONTOGENTIC INFECTIONS Infection Spread Determinants

ODONTOGENTIC INFECTIONS The Host The Organism The Environment In a state of homeostasis, there is Peter A. Vellis, D.D.S. a balance between the three. PROGRESSION OF ODONTOGENIC Infection Spread Determinants INFECTIONS • Location, location , location 1. Source 2. Bone density 3. Muscle attachment 4. Fascial planes “The Path of Least Resistance” Odontogentic Infections Progression of Odontogenic Infections • Common occurrences • Periapical due primarily to caries • Periodontal and periodontal • Soft tissue involvement disease. – Determined by perforation of the cortical bone in relation to the muscle attachments • Odontogentic infections • Cellulitis‐ acute, painful, diffuse borders can extend to potential • fascial spaces. Abscess‐ chronic, localized pain, fluctuant, well circumscribed. INFECTIONS Severity of the Infection Classic signs and symptoms: • Dolor- Pain Complete Tumor- Swelling History Calor- Warmth – Chief Complaint Rubor- Redness – Onset Loss of function – Duration Trismus – Symptoms Difficulty in breathing, swallowing, chewing Severity of the Infection Physical Examination • Vital Signs • How the patient – Temperature‐ feels‐ Malaise systemic involvement >101 F • Previous treatment – Blood Pressure‐ mild • Self treatment elevation • Past Medical – Pulse‐ >100 History – Increased Respiratory • Review of Systems Rate‐ normal 14‐16 – Lymphadenopathy Fascial Planes/Spaces Fascial Planes/Spaces • Potential spaces for • Primary spaces infectious spread – Canine between loose – Buccal connective tissue – Submandibular – Submental -

TAR and Non-Benefit List: Codes 40000 Thru 49999 Page Updated: January 2021

tar and non cd4 1 TAR and Non-Benefit List: Codes 40000 thru 49999 Page updated: January 2021 Surgery Digestive System Note: Refer to the TAR and Non-Benefit: Introduction to List in this manual for more information about the categories of benefit restrictions. Lips Excision Code Description Benefit Restrictions 40490 Biopsy of lip Assistant Surgeon services not payable Other Procedures Code Description Benefit Restrictions 40799 Unlisted procedure, lips Requires TAR, Primary Surgeon/ Provider Vestibule of Mouth Incision Code Description Benefit Restrictions 40800 Drainage of abscess/cyst, mouth, simple Assistant Surgeon services not payable 40801 Drainage of abscess/cyst, mouth, complicated Assistant Surgeon services not payable 40804 Removal of embedded foreign body, mouth, simple Assistant Surgeon services not payable 40805 Removal of embedded foreign body, mouth, Assistant Surgeon complicated services not payable 40806 Incision labial frenum Non-Benefit Excision Code Description Benefit Restrictions 40808 Biopsy, vestibule of mouth Assistant Surgeon services not payable 40810 Excision of lesion mucosa/submucosa, mouth, without Non-Benefit repair Part 2 – TAR and Non-Benefit List: Codes 40000 thru 49999 tar and non cd4 2 Page updated: January 2021 Excision (continued) Code Description Benefit Restrictions 40812 Excision of lesion mucosa/submucosa, mouth, simple Assistant Surgeon repair services not payable 40816 Excision of lesion, mouth, mucosa/submucosa, Assistant Surgeon complex services not payable 40819 Excision of frenum, labial -

Acute Fascial Space Abscess Upon Dental Implantation to Patients with Diabetes Mellitus

CASE REPORT J Korean Dent Sci. 2015;8(2):89-94 http://dx.doi.org/10.5856/JKDS.2015.8.2.89 ISSN 2005-4742 Acute Fascial Space Abscess upon Dental Implantation to Patients with Diabetes Mellitus Chae Yoon Lee, Baek Soo Lee, Yong Dae Kwon, Joo Young Oh, Jung Woo Lee, Suk Huh, Byeong Joon Choi Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, School of Dentistry, Kyung Hee University, Seoul, Korea As popularity of dental implantation is increasing, the number of cases associated with complications also increase. Evaluation on diabetes mellitus is often neglected due to the disease's irrelevance to implantability. However, patients with diabetes mellitus are susceptible to infection due to impaired bactericidal ability of neutrophils, cellular immunity and activity of complements. Due to this established connection between diabetes mellitus and infection, a couple of cases were selected to present patients with diabetes mellitus with glycemic incontrollability, suffering from post-implantation dentigerous inter-fascial space abscess. Key Words: Deep neck abscess; Diabetes mellitus; Implant complication; Klebsiella pneumoniae Introduction to other conditions involved with administration of anticoagulant formulation and bisphosphonate As popularity of dental implantation is increasing, formulation associated with bisphosphonate-related the number of cases associated with complications osteonecrosis of the jaw (BRONJ) which have direct also increase. While there are plenty of researches association with implantability. on locally manifested etiological causes of dental Being the most common systemic disease affecting implant failure, systemic causes have barely been infection of deep neck, diabetes mellitus hinders studied and reported. In clinical settings, there is immunity1) and causes prolonged healingwith poor insufficient evaluation of systemic factors prior to prognosis1). -

Deep Neck Space Infection

European Journal of Molecular & Clinical Medicine ISSN 2515-8260 Volume 07, Issue 03, 2020 DEEP NECK SPACE INFECTION- A CLINICAL INSIGHT Correspondance to:Dr.Vijay Ebenezer 1, Professor Head of the department of oral and maxillofacial surgery, Sree balaji dental college and hospital, pallikaranai, chennai-100. Email id: [email protected], Contact no: 9840136328 Names of the author(s): 1)Dr. Vijay Ebenezer1 ,Professor and Head of the department of oral and maxillofacial surgery, Sree Balaji dental college and hospital , BIHER, Chennai-600100, Tamilnadu , India. 2)Dr. Balakrishnan Ramalingam2, professor in the department of oral and maxillofacial surgery, Sree balaji dental college and hospital, pallikaranai, chennai-100. INTRODUCTION Deep neck infections are a life threatening condition but can be treated, the infections affects the deep cervical space and is characterized by rapid progression. These infections remains as a serious health problem with significant morbidity and potential mortality. These infections most frequently has its origin from the local extension of infections from tonsils, parotid glands, cervical lymph nodes, and odontogenic structures. Classically it presents with symptoms related to local pressure effects on the respiratory, nervous, or gastrointestinal (GI) tract (particularly neck mass/swelling/induration, dysphagia, dysphonia, and trismus). The specific presenting symptoms will be related to the deep neck space involved (parapharyngeal, retropharyngeal, prevertebral, submental, masticator, etc).1,2,3,4,5 ETIOLOGY Deep neck space infections are polymicrobial, with their source of origin from the normal flora of the oral cavity and upper respiratory tract. The most common deep neck infections among adults arise from dental and periodontal structures, with the second most common source being from the tonsils. -

Neck Formation and Growth. MAIN TOPOGRAPHIC REGIONS in NECK

Neck formation and growth. MAIN TOPOGRAPHIC REGIONS IN NECK. ANATOMICAL BACKGROUND FOR URGENT LIFE SAVING PERFORMANCES. orofac Ivo Klepáček orofac Vymezení oblasti krku Extent of the neck region Sensitivní oblasti V1, V2, V3., plexus cervicalis orofac * * * * * orofac** * orofac orofac orofaccranial middle caudal orofac orofac Clinical classification of neck lymph nodes orofacClinical classification of neck lymphatic nodes: I - VI Nodi lymphatici out of regiones above: Perifacial, periparotic, retroauricular, suboccipital, retropharyngeal Metastasa v krčních uzlinách Metastasis in cervical orofaclymphonodi TOPOGRAPHIC REGIONS orofacand SPACES Regio colli anterior anterior neck triangle Trigonae : submentale, submandibulare, caroticum (musculare), regio suprasternalis Triangles : submental, submandibular, carotic (muscular), orofacsuprasternal region podkožní sval na povrchové krční fascii r. colli nervi facialis ovládá napětí kůže krku Platysma orofac proc. mastoideus manubrium sterni, clavicula Sternocleidomastoid m. n.accessorius (XI) + branches sternocleidomastoideus from plexus cervicalis orofac Punctum nervosum (Erb ´s point) : there C5 and C6 nerves are connected, + branches from suprascapulari and subclavian nerves orofacWilhelm Heinrich Erb (1840 - 1921), German neurologist orofac orofac mm. suprahyoid suprahyoidei and et mm. infrahyoid orofacinfrahyoidei muscles orofac Thyroid gland and vascular + nerve bundle in neck orofac orofac Žíly veins orofac štítná žláza příštitné orofactělísko a. thyroidea inferior n. laryngeus inferior -

Rare Case of Plunging Ranula with Parapharyngeal Extension and Absent Submandibular Gland: Excision by Transcervical Approach

Central Journal of Ear, Nose and Throat Disorders Bringing Excellence in Open Access Case Report *Corresponding author Abhishek Bhardwaj, Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Safdarjung Hospital Rare Case of Plunging Ranula &Vardhmann Mahavir Medical College, Ansari Nagar, New Delhi-110029, India, Tel: 91-989907792; Email: with Parapharyngeal Extension Submitted: 04 January 2017 Accepted: 29 March 2017 and Absent Submandibular Published: 31 March 2017 ISSN: 2475-9473 Copyright Gland: Excision by Transcervical © 2017 Bhardwaj et al. Approach OPEN ACCESS Keywords Abhishek Bhardwaj*, Sudhagar Eswaran, and Hari Shankar • Ranula Niranjan • Submandibular gland Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Vardhmann Mahavir Medical College and • Pharynx Safdarjung Hospital, India • Skull Base • Neck Abstract Plunging ranula extending into parapharyngeal space till the skull base with associated absence of submandibular gland is a rare finding. Transcervical approach for its excision is a challenging procedure in view of limited exposure and presence of important neurovascular structures in the field. We present a clinical case of a left sided plunging ranula extending into the parapharyngeal space till skull base in a 19 year old male who presented to a tertiary care hospital with complaints of slowly increasing swelling in neck and oral cavity for duration of six months. Ultrasound neck revealed well defined heterogeneously hypoechoic collection in left submandibular region. Contrast enhanced computed tomography revealed a non-enhancing, cystic mass involving left submandibular space extending into left parapharyngeal space till skull base and absent left submandibular gland. Ranula measuring 10cm*6cm was excised in to by tanscervical approach without damage to any neurovascular structure. Histopathology was consistent with low ranula. Patient is in follow up for past six months without any recurrence. -

Deep Neck Space Infectionsdeep Neck Space Infections

Deep Neck Space InfectionsDeep Neck Space Infections Disclaimer: The pictures used in this presentation and its content has been obtained from a number of sources. Their use is purely for academic and teaching purposes. The contents of this presentation do not have any intended commercial use. In case the owner of any of the pictures has any objection and seeks their removal please contact at [email protected] . These pictures will be removed immediately. The fibrous connective tissue that constitutes the cervical fascia varies from loose areolar tissue to dense fibrous bands. This fascia serves to envelope the muscles, nerves, vessels and viscera of the neck, thereby forming planes and potential spaces that serve to divide the neck into functional units. It functions to both direct and limit the spread of disease processes in the neck. The cervical fascia can be divided into a simpler superficial layer and a more complex deep layer that is further subdivided into superficial, middle and deep layers. The superficial layer of cervical fascia ensheaths the platysma in the neck and extends superiorly in the face to cover the mimetic muscles. It is the equivalent of subcutaneous tissue elsewhere in the body and forms a continuous sheet from the head and neck to the chest, shoulders and axilla. The superficial layer of the deep cervical fascia is also known as the investing layer. It follows the “rule of twos”—it envelops two muscles, two glands and forms two spaces. It originates from the spinous processes of the vertebral column and spreads circumferentially around the neck. -

Suprahyoid and Infrahyoid Neck Overview

Suprahyoid and Infrahyoid Neck Overview Imaging Approaches & Indications by space, the skull base interactions above and IHN extension below are apparent. Neither CT nor MR is a perfect modality for imaging the • PPS has bland triangular skull base abutment without extracranial H&N. MR is most useful in the suprahyoid neck critical foramen involved; it empties inferiorly into (SHN) because it is less affected by oral cavity dental amalgam submandibular space (SMS) artifact. The SHN tissue is less affected by motion compared • PMS touches posterior basisphenoid and anterior with the infrahyoid neck (IHN); therefore, the MR image basiocciput, including foramen lacerum; PMS includes quality is not degraded by movement seen in the IHN. Axial nasopharyngeal, oropharyngeal, and hypopharyngeal and coronal T1 fat-saturated enhanced MR is superior to CECT mucosal surfaces in defining soft tissue extent of tumor, perineural tumor • MS superior skull base interaction includes zygomatic spread, and dural/intracranial spread. When MR is combined with CT of the facial bones and skull base, a clinician can obtain arch, condylar fossa, skull base, including foramen ovale (CNV3), and foramen spinosum (middle meningeal precise mapping of SHN lesions. Suprahyoid and Infrahyoid Neck artery); MS ends at inferior surface of body of mandible CECT is the modality of choice when IHN and mediastinum are • PS abuts floor of external auditory canal, mastoid tip, imaged. Swallowing, coughing, and breathing makes this area including stylomastoid foramen (CNVII); parotid tail a "moving target" for the imager. MR image quality is often extends inferiorly into posterior SMS degraded as a result. Multislice CT with multiplanar • CS meets jugular foramen (CNIX-XI) floor, hypoglossal reformations now permits exquisite images of the IHN canal (CNXII), and petrous internal carotid artery canal; unaffected by movement. -

Complex Odontogenic Infections

Complex Odontogenic Infections Larry ). Peterson CHAPTEROUTLINE FASCIAL SPACE INFECTIONS Maxillary Spaces MANDIBULAR SPACES Secondary Fascial Spaces Cervical Fascial Spaces Management of Fascial Space Infections dontogenic infections are usually mild and easily and causes infection in the adjacent tissue. Whether or treated by antibiotic administration and local sur- not this becomes a vestibular or fascial space abscess is 0 gical treatment. Abscess formation in the bucco- determined primarily by the relationship of the muscle lingual vestibule is managed by simple intraoral incision attachment to the point at which the infection perfo- and drainage (I&D) procedures, occasionally including rates. Most odontogenic infections penetrate the bone dental extraction. (The principles of management of rou- in such a way that they become vestibular abscesses. tine odontogenic infections are discussed in Chapter 15.) On occasion they erode into fascial spaces directly, Some odontogenic infections are very serious and require which causes a fascial space infection (Fig. 16-1). Fascial management by clinicians who have extensive training spaces are fascia-lined areas that can be eroded or dis- and experience. Even after the advent of antibiotics and tended by purulent exudate. These areas are potential improved dental health, serious odontogenic infections spaces that do not exist in healthy people but become still sometimes result in death. These deaths occur when filled during infections. Some contain named neurovas- the infection reaches areas distant from the alveolar cular structures and are known as coinpnrtments; others, process. The purpose of this chapter is to present which are filled with loose areolar connective tissue, are overviews of fascial space infections of the head and neck known as clefts. -

Factors Affecting the Necessity of Tracheostomy in Patients with Deep Neck Infection

diagnostics Article Factors Affecting the Necessity of Tracheostomy in Patients with Deep Neck Infection Shih-Lung Chen 1,2 , Chi-Kuang Young 2,3, Tsung-You Tsai 1,2 , Huei-Tzu Chien 2,4 , Chung-Jan Kang 1,2 , Chun-Ta Liao 1,2 and Shiang-Fu Huang 1,5,* 1 Department of Otorhinolaryngology & Head and Neck Surgery, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Linkou 333, Taiwan; [email protected] (S.-L.C.); [email protected] (T.-Y.T.); [email protected] (C.-J.K.); [email protected] (C.-T.L.) 2 School of Medicine, Chang Gung University, Taoyuan 333, Taiwan; [email protected] (C.-K.Y.); [email protected] (H.-T.C.) 3 Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Keelung 204, Taiwan 4 Department of Nutrition and Health Sciences, Chang Gung University of Science and Technology, Taoyuan 333, Taiwan 5 Graduate Institute of Clinical Medical Sciences, Chang Gung University, Taoyuan 333, Taiwan * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +886-3-3281200 (ext. 3972); Fax: +886-3-3979361 Abstract: Deep neck infection (DNI) is a serious disease that can lead to airway obstruction, and some patients require a tracheostomy to protect the airway instead of intubation. However, no previous study has explored risk factors associated with the need for a tracheostomy in patients with DNI. This article investigates the risk factors for the need for tracheostomy in patients with DNI. Between September 2016 and February 2020, 403 subjects with DNI were enrolled. Clinical findings and critical deep neck spaces associated with a need for tracheostomy in patients with DNI were assessed. -

A Guide to Deep Neck Space Fascial Infections for the Dental Team

Main, B. , Collin, J., Coyle, M., Hughes, C., & Thomas, S. (2017). A guide to deep neck space fascial infections for the dental team. Dental Update, 43(8), 745-752. https://doi.org/10.12968/denu.2016.43.8.745 Peer reviewed version Link to published version (if available): 10.12968/denu.2016.43.8.745 Link to publication record in Explore Bristol Research PDF-document This is the accepted author manuscript (AAM). The final published version (version of record) is available online via George Warman Publications at http://www.dental-update.co.uk/articleMatchListArticle.asp?aKey=1577. Please refer to any applicable terms of use of the publisher. University of Bristol - Explore Bristol Research General rights This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the reference above. Full terms of use are available: http://www.bristol.ac.uk/red/research-policy/pure/user-guides/ebr-terms/ Oral Surgery A guide to deep neck space fascial infections for the dental team Authors: Mr Barry Main MRCS (Ed), MFDS (Ed), MB ChB (Hons), BDS (Hons), BMSc (Hons) Doctoral Research Fellow and Honorary Specialty Registrar in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, School of Oral and Dental Science, University of Bristol, Lower Maudlin Street, Bristol BS1 2LY Mr John Collin BSc, MB ChB, MRCS, BDS Specialty Registrar in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, Division of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, School of Oral and Dental Science, University of Bristol, Lower Maudline Street, Bristol BS1 2LY Ms Margaret Coyle BA,