Imaging of the Sublingual and Submandibular Spaces

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

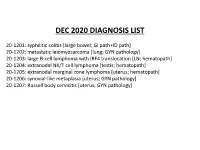

Dec 2020 Summary Slides

DEC 2020 DIAGNOSIS LIST 20-1201: syphilitic colitis [large bowel; GI path+ID path] 20-1202: metastatic leiomyosarcoma [lung; GYN pathology] 20-1203: large B-cell lymphoma with IRF4 translocation [LN; hematopath] 20-1204: extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma [testis; hematopath] 20-1205: extranodal marginal zone lymphoma [uterus; hematopath] 20-1206: synovial-like metaplasia [uterus; GYN pathology] 20-1207: Russell body cervicitis [uterus; GYN pathology] Disclosures December 7, 2020 Dr. Ankur Sangoi has disclosed a financial relationship with Google (consultant). South Bay Pathology Society has determined that this relationship is not relevant to the planning of the activity or the clinical cases being presented. The following planners and faculty had no financial relationships with commercial interests to disclose: Presenters: Activity Planners/Moderator: Natalie Patel, MD Kristin Jensen, MD Mahendra Ranchod, MD Megan Troxell, MD, PhD Ashley Volaric, MD Yaso Natkunam, MD, PhD Neslihan Kayraklioglu, MD Robert Ohgami, MD, PhD Josh Menke, MD Charles Lombard, MD 20-1201 scanned slide avail! Natalie Patel; El Camino Hospital 58-year-old M, reported h/o IBD/UC. Recently presented with rectal bleeding, stool cultures negative for C.diff. Patient put back on mesalamine and bleeding improved, however continued to have discomfort. Left colon/rectal biopsy performed, rule out CMV. IHCs • Warthin starry: Negative • CMV: Negative • Treponema pallidum: Positive Treponema pallidum IHC Treponema pallidum immunostain Findings • Colonoscopy: Rectal ulceration • History of colitis for 3 years – diagnosis of ulcerative colitis on mesalamine • History of unprotected sex with men 4 months prior • Tests: • 1. HIV/Hep B/Tb/Gonorrhea/chlamydia: negative • 2. RPR: Reactive (titer: 1:256 ) • 3. -

29360-Oral Cavity Dr. Alexandra Borges.Pdf

ORAL CAVITY: ANATOMY AND PATHOLOGIES Alexandra Borges, MD COI Disclosure Instituto Português de Oncologia de Lisboa I have nothing to disclose Champalimaud Foundation Lisbon, Portugal ECHNNR 2021 ECHNNR 2021 MR ANATOMY LEARNING OBJECTIVES • Become familiar with OC anatomy and the importance of using adequate terminology when reporting OC studies NASOPHARYNX NASAL CAVITY • Learn how to tailor imaging studies • Understand the different patterns of malignant tumor spread according to the different tumor subsites OROPHARYNX ORAL CAVITY HYPOPHARYNX BOUNDARIES CONTENTS: ORAL TONGUE Superior: • hard palate • superior alveolar ridge Inferior: • floor of the mouth • inferior alveolar ridge ITM Laterally: • cheeks and buccal mucosaosa Anterior: • Lips Posterior: • oropharynx ORAL TONGUE: Extrinsic tongue muscles EM: Styloglossus tongue retraction and elevation Styloglossus Palatoglossus Hyoglossus SG Geniglossus HG GG CN XII CN X EM: Palatoglossus elevation of the tongue EM: Hyoglossus tongue depression and retraction EM: Genioglossus tongue protrusion ORAL TONGUE: Extrinsic muscles GG GH TONGUE INNERVATION ORAL CAVITY IX sensitive and Spatial subdivision taste CN X Motor • Mucosal area • Tongue root • Sublingual space CN XII Motor • Submandibular space Lingual nerve: Sensitive (branch of V3) • Buccomasseteric region Taste (chorda tympani) ORAL MUCOSAL SPACE ROOT OF THE TONGUE 1. Lips 2. Gengiva (sup. alveolar ridge) 3. Gengiva (inf. alveolar ridge) 4. Buccal 5. Palatal 6. Sublingual/FOM 7. Retromolar trigone GG 8. Tongue ROT BOT Vestibule GH Mucosa -

Deep Neck Infections 55

Deep Neck Infections 55 Behrad B. Aynehchi Gady Har-El Deep neck space infections (DNSIs) are a relatively penetrating trauma, surgical instrument trauma, spread infrequent entity in the postpenicillin era. Their occur- from superfi cial infections, necrotic malignant nodes, rence, however, poses considerable challenges in diagnosis mastoiditis with resultant Bezold abscess, and unknown and treatment and they may result in potentially serious causes (3–5). In inner cities, where intravenous drug or even fatal complications in the absence of timely rec- abuse (IVDA) is more common, there is a higher preva- ognition. The advent of antibiotics has led to a continu- lence of infections of the jugular vein and carotid sheath ing evolution in etiology, presentation, clinical course, and from contaminated needles (6–8). The emerging practice antimicrobial resistance patterns. These trends combined of “shotgunning” crack cocaine has been associated with with the complex anatomy of the head and neck under- retropharyngeal abscesses as well (9). These purulent col- score the importance of clinical suspicion and thorough lections from direct inoculation, however, seem to have a diagnostic evaluation. Proper management of a recog- more benign clinical course compared to those spreading nized DNSI begins with securing the airway. Despite recent from infl amed tissue (10). Congenital anomalies includ- advances in imaging and conservative medical manage- ing thyroglossal duct cysts and branchial cleft anomalies ment, surgical drainage remains a mainstay in the treat- must also be considered, particularly in cases where no ment in many cases. apparent source can be readily identifi ed. Regardless of the etiology, infection and infl ammation can spread through- Q1 ETIOLOGY out the various regions via arteries, veins, lymphatics, or direct extension along fascial planes. -

Marginal Zone Lymphoma

311 Original Article Marginal Zone Lymphoma Omid S. Shaye, MD, and Alexandra M. Levine, MD, Los Angeles, California Key Words common of the 3 subtypes is extranodal MZL of MALT Marginal zone lymphoma, MALT lymphoma, splenic marginal zone type, which represents 8% of non-Hodgkin lymphomas.3 lymphoma, nodal marginal zone lymphoma Gastric MALT lymphoma (GML) is the prototype of this entity, with considerable data describing its association Abstract with chronic gastritis secondary to Helicobacter pylori. Marginal zone lymphomas (MZLs) comprise 3 distinct entities: extra- The other MZL subtypes are less common, with SMZL and nodal MZL of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT), splenic MZL, and nodal MZL. Gastric MALT lymphoma is the most common NMZL each composing less than 1% of all lymphomas. extranodal MZL and often develops as a result of chronic Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Such cases frequently respond to antibiotics directed against H. pylori. Antigen-driven lymphomatous disease can also be Extranodal MZL of MALT Type seen in the association of Borrelia burgdorferi with MALT lymphoma Isaacson and Wright4 first described MALT lymphoma of the skin, Chlamydia psittaci with MALT lymphoma of the ocular adnexa, Campylobacter jejuni with immunoproliferative disease of in 1983. Since then, the unique pathogenesis of disease, the small intestine, and hepatitis C with splenic MZL. This article dis- which is related to antigen-induced proliferation of lym- cusses the pathogenesis and clinical features of MZL and the treat- phoid tissue, has received increasing attention. MALT ment options available to patients. (JNCCN 2006;4:311–318) can be found in 2 situations. The usual and normal form consists of lymphoid tissue present in specific areas in the In 1994, the Revised European-American Lymphoma gut, such as Peyer patches. -

The Oromaxillofacial Rehabilitation in Orthodontic-Surgical Protocols

DOI: 10.1051/odfen/2015044 J Dentofacial Anom Orthod 2016;19:203 © The authors The oromaxillofacial rehabilitation in orthodontic-surgical protocols Th. Gouzland1,2, M. Fournier1 1 Kinesiologist, specializing in oromaxillofacial rehabilitation 2 Educator SUMMARY Oro-maxillo-facial rehabilitation is an ancient practice that has developed over recent years through research and integration with physiotherapists in multidisciplinary teams, as is the case with orthodontic- surgical procedures. At the same time, the progress made in orthognathic and orthodontic surgery over the last 20 years encourages more and more patients to undergo surgery. Preoperative treatment is based on early assessment and preparation for optimal surgical conditions to come up with a functional plan. A short stay in a hospital, focusing on rehabilitation, is recommended. During the postoperative phase, the key objectives are to ensure the muscles and arteries all function perfectly, acceptance of the new face, and the immediate correction of any orofacial dyspraxia that has occurred during myofunc- tional therapy. The various specialists in this multidisciplinary team must constantly be in communication. The importance of postoperative physiotherapy will be illustrated by a study consisting of 35 cases of maxillomandibular osteotomy with orthodontic preparation and monitoring. The purpose of this study is to show occurrence of suboccipital and cervical muscle tensions as well as masticatory muscles. Then we will be able to see the importance of these practices, the impact on recovery, the impact on posture and how best to treat. KEYWORDS Physiotherapy, orthognathic surgery, orthodontic, myofunctional therapy, muscles, posture INTRODUCTION The progress made in the techniques and comfortable recovery. This fits into and the results obtained by coupling the current social view where one’s orthognathic surgery with orthodontics image is given greater importance. -

ODONTOGENTIC INFECTIONS Infection Spread Determinants

ODONTOGENTIC INFECTIONS The Host The Organism The Environment In a state of homeostasis, there is Peter A. Vellis, D.D.S. a balance between the three. PROGRESSION OF ODONTOGENIC Infection Spread Determinants INFECTIONS • Location, location , location 1. Source 2. Bone density 3. Muscle attachment 4. Fascial planes “The Path of Least Resistance” Odontogentic Infections Progression of Odontogenic Infections • Common occurrences • Periapical due primarily to caries • Periodontal and periodontal • Soft tissue involvement disease. – Determined by perforation of the cortical bone in relation to the muscle attachments • Odontogentic infections • Cellulitis‐ acute, painful, diffuse borders can extend to potential • fascial spaces. Abscess‐ chronic, localized pain, fluctuant, well circumscribed. INFECTIONS Severity of the Infection Classic signs and symptoms: • Dolor- Pain Complete Tumor- Swelling History Calor- Warmth – Chief Complaint Rubor- Redness – Onset Loss of function – Duration Trismus – Symptoms Difficulty in breathing, swallowing, chewing Severity of the Infection Physical Examination • Vital Signs • How the patient – Temperature‐ feels‐ Malaise systemic involvement >101 F • Previous treatment – Blood Pressure‐ mild • Self treatment elevation • Past Medical – Pulse‐ >100 History – Increased Respiratory • Review of Systems Rate‐ normal 14‐16 – Lymphadenopathy Fascial Planes/Spaces Fascial Planes/Spaces • Potential spaces for • Primary spaces infectious spread – Canine between loose – Buccal connective tissue – Submandibular – Submental -

The Impact of Neutrophils on the Sensitivity of Lymphoma B Cells to Cancer Therapy Taghreed Hirz

Polymorphonuclear neutrophils and cancer : the impact of neutrophils on the sensitivity of lymphoma B cells to cancer therapy Taghreed Hirz To cite this version: Taghreed Hirz. Polymorphonuclear neutrophils and cancer : the impact of neutrophils on the sensi- tivity of lymphoma B cells to cancer therapy. Cancer. Université Claude Bernard - Lyon I, 2015. English. NNT : 2015LYO10327. tel-01417800 HAL Id: tel-01417800 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01417800 Submitted on 16 Dec 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. No d’ordre 327-2015 Année 2015 THESE DE L’UNIVERSITE DE LYON Délivrée par L’UNIVERSITE CLAUDE BERNARD LYON I ECOLE DOCTORALE BIOLOGIE MOLECULAIRE, INTEGRATIVE ET CELLULAIRE DIPLOME DE DOCTORAT (arrêté du 7 août 2006) soutenue publiquement le 14 Décembre 2015 par HIRZ Taghreed TITRE Neutrophiles polymorphonucléaires et cancer: L'impact des neutrophiles sur la sensibilité des cellules de lymphome B aux thérapies anti-cancéreuses Directeur de thèse : DUMONTET Charles Jury: Mme. Catherine THIEBLEMONT, Professeure, Paris, France M. Christophe CAUX, Directeur de Recherche, Université Lyon 1, France M. Charles DUMONTET, Professeur, Université Lyon 1, France M. Sebastien JAILLON, Directeur de Recherche, Milan, I UNIVERSITE CLAUDE BERNARD - LYON 1 Président de l’Université M. -

The Bacterial Microbiota of Gastrointestinal Cancers: Role in Cancer Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Perspectives

Clinical and Experimental Gastroenterology Dovepress open access to scientific and medical research Open Access Full Text Article REVIEW The Bacterial Microbiota of Gastrointestinal Cancers: Role in Cancer Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Perspectives This article was published in the following Dove Press journal: Clinical and Experimental Gastroenterology Lina Elsalem1 Abstract: The microbiota has an essential role in the pathogenesis of many gastrointestinal Ahmad A Jum’ah 2 diseases including cancer. This effect is mediated through different mechanisms such as dama- Mahmoud A Alfaqih 3 ging DNA, activation of oncogenic pathways, production of carcinogenic metabolites, stimula- fl Osama Aloudat4 tion of chronic in ammation, and inhibition of antitumor immunity. Recently, the concept of “pharmacomicrobiomics” has emerged as a new field concerned with exploring the interplay 1 Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of between drugs and microbes. Mounting evidence indicates that the microbiota and their meta- Medicine, Jordan University of Science and Technology, Irbid, Jordan; bolites have a major impact on the pharmacodynamics and therapeutic responses toward antic- 2Department of Conservative Dentistry, ancer drugs including conventional chemotherapy and molecular-targeted therapeutics. In Faculty of Dentistry, Jordan University of Science and Technology, Irbid, Jordan; addition, microbiota appears as an attractive target for cancer prevention and treatment. In this 3Department of Physiology and review, we discuss the role of bacterial microbiota -

TAR and Non-Benefit List: Codes 40000 Thru 49999 Page Updated: January 2021

tar and non cd4 1 TAR and Non-Benefit List: Codes 40000 thru 49999 Page updated: January 2021 Surgery Digestive System Note: Refer to the TAR and Non-Benefit: Introduction to List in this manual for more information about the categories of benefit restrictions. Lips Excision Code Description Benefit Restrictions 40490 Biopsy of lip Assistant Surgeon services not payable Other Procedures Code Description Benefit Restrictions 40799 Unlisted procedure, lips Requires TAR, Primary Surgeon/ Provider Vestibule of Mouth Incision Code Description Benefit Restrictions 40800 Drainage of abscess/cyst, mouth, simple Assistant Surgeon services not payable 40801 Drainage of abscess/cyst, mouth, complicated Assistant Surgeon services not payable 40804 Removal of embedded foreign body, mouth, simple Assistant Surgeon services not payable 40805 Removal of embedded foreign body, mouth, Assistant Surgeon complicated services not payable 40806 Incision labial frenum Non-Benefit Excision Code Description Benefit Restrictions 40808 Biopsy, vestibule of mouth Assistant Surgeon services not payable 40810 Excision of lesion mucosa/submucosa, mouth, without Non-Benefit repair Part 2 – TAR and Non-Benefit List: Codes 40000 thru 49999 tar and non cd4 2 Page updated: January 2021 Excision (continued) Code Description Benefit Restrictions 40812 Excision of lesion mucosa/submucosa, mouth, simple Assistant Surgeon repair services not payable 40816 Excision of lesion, mouth, mucosa/submucosa, Assistant Surgeon complex services not payable 40819 Excision of frenum, labial -

Rare Coexistence of Sialolithiasis and Actinomycosis in the Submandibular Gland

Case Report ENT Updates 2016;6(3):148–151 doi:10.2399/jmu.2016003010 Rare coexistence of sialolithiasis and actinomycosis in the submandibular gland O¤uzhan Dikici1, Nuray Bayar Muluk2 1Department of Otorhinolaryngology, fievket Y›lmaz Training and Research Hospital, Bursa, Turkey 2Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Faculty of Medicine, K›r›kkale University, K›r›kkale, Turkey Abstract Özet: Submandibüler bezde siyalolityaz ve aktinomikozun seyrek görülen birlikteli¤i Sialolithiasis is a condition characterized by the obstruction of salivary Siyalolityaz, tükürük bezi veya boflalt›m kanal›n›n bir tafl veya siyalolit gland or its excretory duct by a calculus or sialolith. This condition pro- ile t›kanmas› ile karakterizedir. Bu durum etkilenmifl bezin fliflmesi, a¤- vokes swelling, pain, and infection of affected gland leading to salivary ecta- r›mas› ve enfeksiyonunu teflvik ederek tükürük bezi ektazisine, hatta da- sia and even causing the subsequent dilatation of the salivary gland. The ha sonra tükürük bezinin dilatasyonuna neden olmaktad›r. Bu olgu ra- aim of this case report is to present a rare condition of sialolithiasis of the porunun amac› submandibüler bezde siyalolitle birlikte aktinomikozun submandibular gland with actinomycosis. In this report, we presented a 35- görüldü¤ü nadir bir siyalolityaz olgusunu sunmakt›r. Bu raporda sub- year-old male patient having coexistence of submandibular sialolithiasis mandibüler siyalolit ve aktinomikozu olan 35 yafl›nda erkek hasta litera- and actinomycosis with a literature review. Patient underwent excision of tür taramas› eflli¤inde raporlanm›flt›r. Siyalolityaz nedeniyle sa¤ sub- the right submandibular gland due to siaololithiasis. Pathologic examina- mandibüler bez eksize edilmifltir. Patolojik incelemede gözlemlenen tion revealed chronic sialadenitis, sialolithiasis, actinomyces which all kronik siyaladenit, siyalolityaz ve aktinomiçes nedeniyle çap› 1.5 cm tafl- necessitate the excision of right submandibular gland with stones with 1.5 larla dolu sa¤ submandibüler bezin eksizyonunun gerekti¤i görülmüfl- cm in diameter. -

Deep Neck Space Infection

European Journal of Molecular & Clinical Medicine ISSN 2515-8260 Volume 07, Issue 03, 2020 DEEP NECK SPACE INFECTION- A CLINICAL INSIGHT Correspondance to:Dr.Vijay Ebenezer 1, Professor Head of the department of oral and maxillofacial surgery, Sree balaji dental college and hospital, pallikaranai, chennai-100. Email id: [email protected], Contact no: 9840136328 Names of the author(s): 1)Dr. Vijay Ebenezer1 ,Professor and Head of the department of oral and maxillofacial surgery, Sree Balaji dental college and hospital , BIHER, Chennai-600100, Tamilnadu , India. 2)Dr. Balakrishnan Ramalingam2, professor in the department of oral and maxillofacial surgery, Sree balaji dental college and hospital, pallikaranai, chennai-100. INTRODUCTION Deep neck infections are a life threatening condition but can be treated, the infections affects the deep cervical space and is characterized by rapid progression. These infections remains as a serious health problem with significant morbidity and potential mortality. These infections most frequently has its origin from the local extension of infections from tonsils, parotid glands, cervical lymph nodes, and odontogenic structures. Classically it presents with symptoms related to local pressure effects on the respiratory, nervous, or gastrointestinal (GI) tract (particularly neck mass/swelling/induration, dysphagia, dysphonia, and trismus). The specific presenting symptoms will be related to the deep neck space involved (parapharyngeal, retropharyngeal, prevertebral, submental, masticator, etc).1,2,3,4,5 ETIOLOGY Deep neck space infections are polymicrobial, with their source of origin from the normal flora of the oral cavity and upper respiratory tract. The most common deep neck infections among adults arise from dental and periodontal structures, with the second most common source being from the tonsils. -

Surgical Approaches to the Submandibular Gland: a Review of Literatureq

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector International Journal of Surgery 7 (2009) 503–509 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect International Journal of Surgery journal homepage: www.theijs.com Review Surgical approaches to the submandibular gland: A review of literatureq David D. Beahm a, Laura Peleaz a, Daniel W. Nuss a,b,c, Barry Schaitkin b, Jayc C. Sedlmayr c, Carlos Mario Rivera-Serrano b, Adam M. Zanation d, Rohan R. Walvekar a,* a Department of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, LSU Health Science Center, 533 Bolivar Street, Suite 566 New Orleans, LA 70112, United States b Department of Otolaryngology Head and Neck Surgery, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA, United States c Department of Cell Biology and Anatomy, LSU Health Sciences Center, New Orleans, LA, United States d Department of Otolaryngology Head Neck Surgery, UNC School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, NC article info abstract Article history: Objectives: Surgical excision of the submandibular gland (SMG) is commonly indicated in patients with Received 4 July 2009 neoplasms, and non-neoplastic conditions such as chronic sialadenitis, sialolithiasis, ranula and drooling. Received in revised form Traditional SMG surgery involves a direct transcervical approach. In the recent past, alternative approaches to 4 September 2009 SMG excision have been described in effort to offer minimally invasive options or better cosmetic results. The Accepted 12 September 2009 purpose of this article is to describe the surgical approaches to the SMG and present relevant surgical anatomy Available online 24 September 2009 via cadaveric dissection and a systematic review of literature to compare and contrast each technique.