Marginal Zone Lymphoma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

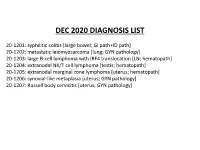

Dec 2020 Summary Slides

DEC 2020 DIAGNOSIS LIST 20-1201: syphilitic colitis [large bowel; GI path+ID path] 20-1202: metastatic leiomyosarcoma [lung; GYN pathology] 20-1203: large B-cell lymphoma with IRF4 translocation [LN; hematopath] 20-1204: extranodal NK/T cell lymphoma [testis; hematopath] 20-1205: extranodal marginal zone lymphoma [uterus; hematopath] 20-1206: synovial-like metaplasia [uterus; GYN pathology] 20-1207: Russell body cervicitis [uterus; GYN pathology] Disclosures December 7, 2020 Dr. Ankur Sangoi has disclosed a financial relationship with Google (consultant). South Bay Pathology Society has determined that this relationship is not relevant to the planning of the activity or the clinical cases being presented. The following planners and faculty had no financial relationships with commercial interests to disclose: Presenters: Activity Planners/Moderator: Natalie Patel, MD Kristin Jensen, MD Mahendra Ranchod, MD Megan Troxell, MD, PhD Ashley Volaric, MD Yaso Natkunam, MD, PhD Neslihan Kayraklioglu, MD Robert Ohgami, MD, PhD Josh Menke, MD Charles Lombard, MD 20-1201 scanned slide avail! Natalie Patel; El Camino Hospital 58-year-old M, reported h/o IBD/UC. Recently presented with rectal bleeding, stool cultures negative for C.diff. Patient put back on mesalamine and bleeding improved, however continued to have discomfort. Left colon/rectal biopsy performed, rule out CMV. IHCs • Warthin starry: Negative • CMV: Negative • Treponema pallidum: Positive Treponema pallidum IHC Treponema pallidum immunostain Findings • Colonoscopy: Rectal ulceration • History of colitis for 3 years – diagnosis of ulcerative colitis on mesalamine • History of unprotected sex with men 4 months prior • Tests: • 1. HIV/Hep B/Tb/Gonorrhea/chlamydia: negative • 2. RPR: Reactive (titer: 1:256 ) • 3. -

The Impact of Neutrophils on the Sensitivity of Lymphoma B Cells to Cancer Therapy Taghreed Hirz

Polymorphonuclear neutrophils and cancer : the impact of neutrophils on the sensitivity of lymphoma B cells to cancer therapy Taghreed Hirz To cite this version: Taghreed Hirz. Polymorphonuclear neutrophils and cancer : the impact of neutrophils on the sensi- tivity of lymphoma B cells to cancer therapy. Cancer. Université Claude Bernard - Lyon I, 2015. English. NNT : 2015LYO10327. tel-01417800 HAL Id: tel-01417800 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-01417800 Submitted on 16 Dec 2016 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. No d’ordre 327-2015 Année 2015 THESE DE L’UNIVERSITE DE LYON Délivrée par L’UNIVERSITE CLAUDE BERNARD LYON I ECOLE DOCTORALE BIOLOGIE MOLECULAIRE, INTEGRATIVE ET CELLULAIRE DIPLOME DE DOCTORAT (arrêté du 7 août 2006) soutenue publiquement le 14 Décembre 2015 par HIRZ Taghreed TITRE Neutrophiles polymorphonucléaires et cancer: L'impact des neutrophiles sur la sensibilité des cellules de lymphome B aux thérapies anti-cancéreuses Directeur de thèse : DUMONTET Charles Jury: Mme. Catherine THIEBLEMONT, Professeure, Paris, France M. Christophe CAUX, Directeur de Recherche, Université Lyon 1, France M. Charles DUMONTET, Professeur, Université Lyon 1, France M. Sebastien JAILLON, Directeur de Recherche, Milan, I UNIVERSITE CLAUDE BERNARD - LYON 1 Président de l’Université M. -

The Bacterial Microbiota of Gastrointestinal Cancers: Role in Cancer Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Perspectives

Clinical and Experimental Gastroenterology Dovepress open access to scientific and medical research Open Access Full Text Article REVIEW The Bacterial Microbiota of Gastrointestinal Cancers: Role in Cancer Pathogenesis and Therapeutic Perspectives This article was published in the following Dove Press journal: Clinical and Experimental Gastroenterology Lina Elsalem1 Abstract: The microbiota has an essential role in the pathogenesis of many gastrointestinal Ahmad A Jum’ah 2 diseases including cancer. This effect is mediated through different mechanisms such as dama- Mahmoud A Alfaqih 3 ging DNA, activation of oncogenic pathways, production of carcinogenic metabolites, stimula- fl Osama Aloudat4 tion of chronic in ammation, and inhibition of antitumor immunity. Recently, the concept of “pharmacomicrobiomics” has emerged as a new field concerned with exploring the interplay 1 Department of Pharmacology, Faculty of between drugs and microbes. Mounting evidence indicates that the microbiota and their meta- Medicine, Jordan University of Science and Technology, Irbid, Jordan; bolites have a major impact on the pharmacodynamics and therapeutic responses toward antic- 2Department of Conservative Dentistry, ancer drugs including conventional chemotherapy and molecular-targeted therapeutics. In Faculty of Dentistry, Jordan University of Science and Technology, Irbid, Jordan; addition, microbiota appears as an attractive target for cancer prevention and treatment. In this 3Department of Physiology and review, we discuss the role of bacterial microbiota -

Extranodal Marginal Zone (Malt) Lymphoma in Common Variable Immunodeficiency

s h o r T r E v i E w Extranodal marginal zone (malT) lymphoma in common variable immunodeficiency I.M.E. Desar1, M. Keuter1, J.M.M. Raemaekers2, J.B.M.J. Jansen3, J.H.J. van Krieken4, J.W.M. van der Meer1* Departments of 1General Internal Medicine, 2Haematology, 3Gastroenterology and Hepatology, and 4Pathology, Radboud University Nijmegen Medical Centre, PO Box 9101, 6500 HB Nijmegen, the Netherlands, *corresponding author: [email protected] AB s T r ACT i NT r o d u CT i o N we describe two patients with common variable In 1983, Isaacson and Wright introduced the term immunodeficiency (CVID) who developed extranodal mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma marginal zone lymphoma (formerly described as to characterise a primary low-grade B-cell lymphoma mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma or MAlT originating in the gut-associated lymphoid tissue.1 lymphoma). one patient, with documented pernicious Nowadays, the nomenclature has been changed to anaemia and chronic atrophic gastritis with metaplasia, extranodal marginal zone lymphoma, representing extra- developed a Helicobacter pylori-positive extranodal marginal nodal low-grade B-cell lymphoma with a similar histology, zone lymphoma in the stomach. Three triple regimens of also occurring in the salivary glands and lungs. antibiotics were necessary to eliminate the H. pylori, after which the lymphoma completely regressed. Patient B had The normal gastric mucosa contains no organised an H. pylori-negative extranodal marginal zone lymphoma lymphoid tissue. Bacterial colonisation of the gastric of the parotid gland, which remarkably regressed after mucosa leads to lymphoid infiltration, which becomes treatment with clarithromycin. -

Helicobacter Pylori Infection in a Mouse Model: Development, Optimization and Inhibitory Effects of Antioxidants Wang

Helicobacter pylori infection in a mouse model: Development, optimization and inhibitory effects of antioxidants Wang, Xin 2001 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Wang, X. (2001). Helicobacter pylori infection in a mouse model: Development, optimization and inhibitory effects of antioxidants. Xin Wang, Dept. of Med. Microbiol., Dermatol. & Infect., Lund University, Sölvegatan 23, S-223 62 Lund, Sweden,. Total number of authors: 1 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 Helicobacter pylori infection in a mouse model Development, optimization and inhibitory effects of antioxidants Xin Wang 2001 Helicobacter pylori infection in a mouse model Development, optimization and inhibitory effects of antioxidants Akademisk avhanding som med vederborligt tillsttind av Medicinska fakulteten vid Lunds Universitet for avlaggande av doktorsexamen i medicinsk vetenskap kommer att offentligen forsvaras i Rune Grubb Salen, BMC, Solvegatan 19, Lund, Fredag den 12 Oktober 200 1, kl. -

Gastric MALT Lymphoma: a Model of Chronic Inflammation-Induced Tumor Development Xavier Sagaert, Eric Van Cutsem, Gert De Hertogh, Karel Geboes and Thomas Tousseyn

REVIEWS Gastric MALT lymphoma: a model of chronic inflammation-induced tumor development Xavier Sagaert, Eric Van Cutsem, Gert De Hertogh, Karel Geboes and Thomas Tousseyn Abstract | Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma, or extranodal marginal zone lymphoma of MALT, is an indolent B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma arising in lymphoid infiltrates that are induced by chronic inflammation in extranodal sites. The stomach is the most commonly affected organ, in which MALT lymphoma pathogenesis is clearly associated with Helicobacter pylori gastroduodenitis. Gastric MALT lymphoma has attracted attention because of the involvement of genetic aberrations in the nuclear factor κB (NFκB) pathway, one of the most investigated pathways in the fields of immunology and oncology. This Review presents gastric MALT lymphoma as an outstanding example of the close pathogenetic link between chronic inflammation and tumor development, and describes how this information can be integrated into daily clinical practice. Gastric MALT lymphoma is considered one of the best models of how genetic events lead to oncogenesis, determine tumor biology, dictate clinical behavior and represent viable therapeutic targets. Moreover, in view of the association of gastric MALT lymphoma with dysregulation of the NFκB pathway, this signaling pathway will be discussed in depth in both normal and pathological conditions, highlighting strategies to identify new therapeutic targets in this lymphoma. Sagaert, X. et al. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 7, 336–346 (2010); published -

Trends of Incidence and Survival Rates of Mucosa-Associated

J Korean Med Sci. 2020 Sep 14;35(36):e294 https://doi.org/10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e294 eISSN 1598-6357·pISSN 1011-8934 Original Article Trends of Incidence and Survival Rates Oncology & Hematology of Mucosa-associated Lymphoid Tissue Lymphoma in the Korean Population: Analysis of the Korea Central Cancer Registry Database Seok-Hoo Jeong ,1 Shin Young Hyun ,2 Ja Sung Choi ,1 and Hee Man Kim 3 1Division of Gastroenterology, Department of Internal Medicine, Catholic Kwandong University International St. Mary's Hospital, Incheon, Korea Received: Jun 1, 2020 2Division of Hematology and Oncology, Yonsei University Wonju College of Medicine, Wonju, Korea Accepted: Jul 16, 2020 3Department of Internal Medicine, Yonsei University Wonju College of Medicine, Wonju, Korea Address for Correspondence: Hee Man Kim, MD, PhD Department of Internal Medicine, Yonsei ABSTRACT University Wonju College of Medicine, 20 Ilsan-ro, Wonju 26426, Republic of Korea. Background: Extranodal marginal zone B-cell lymphoma of mucosa-associated lymphoid E-mail: [email protected] tissue (MALT-lymphoma) is an extranodal lymphoma that occurs at various sites in the © 2020 The Korean Academy of Medical body. There is a limited understanding of the incidence and survival rates of MALT- Sciences. lymphoma. To investigate the nation-wide incidence and survival rates of MALT-lymphoma This is an Open Access article distributed in Korea during 1999–2017, the data on MALT-lymphoma were retrieved from the Korea under the terms of the Creative Commons Central Cancer Registry. Attribution Non-Commercial License (https:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/) Methods: During the time period of 1999–2017, 11,128 patients were diagnosed with MALT- which permits unrestricted non-commercial lymphoma. -

Official WHO Updates Combined 1996 2009 VOLUME 1

Includes proposals ratified by WHO-FIC Network at the annual meeting in Seoul, October 2009 WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION Update and Revision Committee February 2010 CUMULATIVE OFFICIAL UPDATES TO ICD-10 The following pages include the corrigenda (pages 747-750 of Volume 3) and cumulative official changes to the tabular list, instruction manual and alphabetical index of ICD-10 from 1996 to 2009. These changes are approved at the Heads of Centres meetings in October of each year. The source and implementation date for each change has been identified. Date of approval has also been indicated for all changes except the corrigenda. In 1999, the WHO ICD-10 Update Reference Committee (URC) was established. Modifications to the classification that have been recommended following the URC’s inception are uniquely identified and further defined as a major or minor change. Relevant changes in other language versions of ICD-10 and in related tools will also have to be made and disseminated by the appropriate authority. (Note: Every effort has been made in the following pages to reproduce the content of the ICD-10 in the same format as the published volumes. Page references have not been used in all instances since these do not apply to electronic versions of the Classification. Additions/changes have been indicated through the use of instructions, underline and strikeout). This document is not issued to the general public, and all rights are reserved by the World Health Organization (WHO). The document may not be reviewed, abstracted, quoted, reproduced or translated, in part or in whole, without the prior written permission of WHO. -

Submandibular Gland MALT Lymphoma Associated with Sjögren’S Syndrome: Case Report Reza Movahed, DMD,* Adam Weiss, DDS,† Ines Velez, DDS, MS,‡ and Harry Dym, DDS§

J Oral Maxillofac Surg 69:2924-2929, 2011 Submandibular Gland MALT Lymphoma Associated With Sjögren’s Syndrome: Case Report Reza Movahed, DMD,* Adam Weiss, DDS,† Ines Velez, DDS, MS,‡ and Harry Dym, DDS§ Lymphoma is a common disease of the head and neck. Mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma constitutes a rare type of extranodal lymphoma. The Waldeyer’s ring is one of the most common sites of occurrence, but MALT lymphoma may also arise in salivary glands, lung, stomach, or lacrimal glands. In the oral cavity, it may be confused with swellings from dental infection or sinus inflammation. Often, the patient will seek a dentist because of mobile teeth or because a denture no longer fits. We report a case of a female patient with salivary gland dysfunction and pain of several years’ duration, who, after numerous tests and hospitalizations, was diagnosed with Sjögren’s syndrome. She later developed mucosal-associated lymphoid tissue lymphoma. We discuss the diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of this entity. MALT lymphoma is rare in salivary glands. In primary-Sjögren’s syndrome, predisposition of the patient for development of malignant non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (4% to 10%) is well established. In this case, long-standing sialadenitis and Sjögren’s syndrome seem to be the etiological factors. In cases of chronic infection of salivary glands and the presence of autoimmune syndromes, MALT lymphoma should be considered in the differential diagnosis. Consults should be called to ophthalmology, rheumatology, and head and neck oncologists for proper workup, staging, and treat- ment. This is a US government work. There are no restrictions on its use. -

Long-Term Clinical Outcome and Predictive Factors for Relapse After

cancers Article Long-Term Clinical Outcome and Predictive Factors for Relapse after Radiation Therapy in 145 Patients with Stage I Gastric B-Cell Lymphoma of Mucosa-Associated Lymphoid Tissue Type Heerim Nam 1 , Do Hoon Lim 2,*, Jae J. Kim 3, Jun Haeng Lee 3, Byung-Hoon Min 3 and Hyuk Lee 3 1 Department of Radiation Oncology, Kangbuk Samsung Hospital, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul 03181, Korea; [email protected] 2 Department of Radiation Oncology, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul 06351, Korea 3 Department of Medicine, Samsung Medical Center, Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Seoul 06351, Korea; [email protected] (J.J.K.); [email protected] (J.H.L.); [email protected] (B.-H.M.); [email protected] (H.L.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-2-3410-2619 Simple Summary: Helicobacter pylori-associated gastric low-grade B-cell lymphoma of mucosa- associated lymphoid tissue type (MALT lymphoma) constitutes >80% of gastric MALT lymphoma. Eradication therapy has been accepted as a standard approach for initial treatment. However, in patients who present without evidence of infection or who fail to respond to eradication therapy, a solid consensus for treatment is not available. Furthermore, few studies have evaluated the predictive factors for response or relapse after radiation therapy (RT) as heterogeneous, relatively small study populations have been treated with RT, and only a small number of events have been reported after treatment. In this study, we report the long-term clinical outcome of stage I gastric MALT lymphoma treated with RT. We also identified that the tumor’s dominant location in the Citation: Nam, H.; Lim, D.H.; Kim, stomach is a predictive factor for relapse after RT. -

Post-Immunisation Gastritis and Helicobacter Infection in the Mouse: a Long Term Study

Gut 2001;49:467–473 467 PAPERS Gut: first published as 10.1136/gut.49.4.467 on 1 October 2001. Downloaded from Post-immunisation gastritis and Helicobacter infection in the mouse: a long term study P Sutton, S J Danon, M Walker, L J Thompson, J Wilson, T Kosaka, A Lee Abstract Helicobacter pylori is a Gram negative bacterium Background and aims—Helicobacter py- which infects solely the gastric mucosa. It has a lori is a major cause of peptic ulcers and known association with peptic ulcers, gastric gastric cancer. Vaccine development is cancer, and mucosal associated lymphoid progressing but there is concern that tissue (MALT) lymphoma.1–3 The current immunisation may exacerbate Helico- eradication regimen for infection is antimicro- bacter induced gastritis: prophylactic im- bial therapy and concurrent acid suppression. munisation followed by challenge with H Unfortunately, the development of antibiotic felis or H pylori can induce a more severe resistant strains of H pylori is already raising concerns about the long term use of these gastritis in mice than seen with infection 4 alone. The aim of this study was to investi- combination treatments. For this reason, much attention has focused on the production gate the relationship between immunity of an eVective vaccine. Using mouse models of to Helicobacter infection and post- infection with H pylori or the closely related H immunisation gastritis. felis, it has been shown that immunisation with Methods—(1) C57BL/6 mice were prophy- whole cell sonicate or single antigens protects lactically immunised before challenge mice against later bacterial challenge5–10 or even with either H felis or H pylori. -

16.Ijans-Hipotetical Possibilities of Development of Non Hodkins Lymphoma During Lyme Borreliosis

International Journal of Applied and Natural Sciences (IJANS); ISSN Print: 2319-4014; ISSN online: 2319-4022; Vol. 8, Issue 3, Apr - May 2019; 161-176 © IASET HYPOTHETICAL POSSIBILITIES OF DEVELOPMENT OF NON-HODGKINS LYMPHOMA DURING LYME BORRELIOSIS Bogdanka Andric, Brankica Dupanovic, Snezana Dragas, Stefan Mikic, Marko Vukovic & Bogdan Pajovic Medical Faculty, University of Montenegro, Podgorica, Montenegro ABSTRACT The hypothetical possibilities of the infectious genesis of malignant diseases in the past could not be confirmed, in proportion to the degree of development of science and technology development level. Contemporaneous medicine has numerous proves of these possibilities. Among them, the evident coherency of borrelia burgdorfferi (bb) with different kinds of primary skin lymphoma (1), but it is certainly necessary to do a lot of additional scientific research to get the exact answers to many unknown immunogenic mechanisms, which bring to that condition. Modern studies show great difference and prevalence rates, which could be consequence of geographical heterogeneity and variability of bb, and common participation of numerous other zoonotic and non-zoonotic agents in co- transmission, co-infections and their contribution to chronic Lyme borreliosis (LB), as well as many other factors, which usually proceed to a development of malignant diseases (2). Our investigation during the period from 2015 - 2018, even in modest possibilities and confined diagnostic conditions, were directed onto four cases, in which epidemiological, clinical data, laboratory and pathohystological diagnostic allowed assumptions about possibilities that bb is the causer and/or actuator of malignant course of the disease. In diagnosis, besides serological Elisa test onto specific bb antibodies, and confirmative (WB) test was used too.