The Limits of the Unlimited Attitudes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhism Key Terms Pairs

Pairs! Cut out the pairs and challenge your classmate to a game of pairs! There are a number of key terms each of which correspond to a teaching or belief. The key concepts are those that are underlined and the others are general words to help your understanding of the concepts. Can you figure them out? Practicing Doctrine of single-pointed impermanence – Non-injury to living meditation through which states nothing things; the doctrine of mindfulness of Anicca ever is but is always in Samatha Ahimsa non-violence. breathing in order to a state of becoming. calm the mind. ‘Foe Destroyer’. A person Phenomena arising who has destroyed all The Buddhist doctrine together in a mutually delusions through Anatta of no-self. Pratitya interdependent web of Arhat training on the spiritual cause and effect. path. They will never be reborn again in Samsara. A person who has Loving-kindness generated spontaneous meditation practiced bodhichitta but who Pain, suffering, disease Metta in order to ‘cultivate has not yet become a and disharmony. Bodhisattva Dukkha loving-kindness’ Buddha; delaying their Bhavana towards others. parinirvana in order to help mankind. Meditation practiced in (Skandhas – Sanskrit): Theravada Buddhism The four sublime The five aggregates involving states: metta, karuna, which make up the Brahmavihara Khandas Vipassana concentration on the mudita and upekkha. self, as we know it. body or its sensations. © WJEC CBAC LTD 2016 Pairs! A being who has completely abandoned Liberation and true Path to the cessation all delusions and their cessation of the cycle of suffering – the Buddha imprints. In general, Enlightenment of Samsara. -

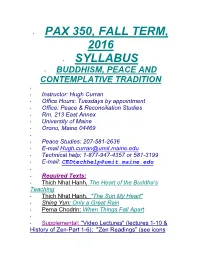

Pax 350, Fall Term, 2016 Syllabus

• PAX 350, FALL TERM, 2016 • SYLLABUS • BUDDHISM, PEACE AND CONTEMPLATIVE TRADITION • • Instructor: Hugh Curran • Office Hours: Tuesdays by appointment • Office: Peace & Reconciliation Studies • Rm. 213 East Annex • University of Maine • Orono, Maine 04469 • • Peace Studies: 207-581-2636 • E-mail [email protected] • Technical help: 1-877-947-4357 or 581-3199 • E-mail: [email protected] • • Required Texts: • Thich Nhat Hanh, The Heart of the Buddha’s Teaching • Thich Nhat Hanh, "The Sun My Heart" • Shing Yun: Only a Great Rain • Pema Chodrin: When Things Fall Apart • • Supplemental: “Video Lectures" (lectures 1-10 & History of Zen-Part 1-6); "Zen Readings” (see icons above lessons): Articles include: The Way of Zen; The Spirit of Zen; Mysticism; Sermons of a Buddhist Abbot ;Dharma Rain; • • Recommended: • Donald Lopez, “The Story of Buddhism” • Dalai Lama: How to Practice Thich Nhat Hanh:"Commentaries on the Heart Sutra" • • The UMA Bookstore 800 number is: 1-800-621- 0083 • The Fax number of the UMA Bookstore is: 1-800- 243-7338The UM Bookstore number is:1-207- 581- 1700 and e-mail at [email protected] • • Course Objective: • Course Objective: • This course is designed as an introduction to Buddhism, especially the practice of Zen (Ch'an). We will examine spiritual & ethical aspects including stories, sutras, ethical precepts, ecological issues, and how we can best embody the Way in our daily lives. • • University Policy: • In complying with the letter and spirit of applicable laws and in pursuing its own goals of pluralism, the University of Maine shall not discriminate on the grounds of race, color, religion, sex, sexual orientation, national origin or citizenship status, age, disability, or veterans status in employment, education, and all other areas of the University. -

The Role of the Brahmavihāra in Psychotherapeutic Practice

THE ROLE OF THE BRAHMAVIHĀRA IN PSYCHOTHERAPEUTIC PRACTICE The following is an essay written early in 2006 for an MA-course in Buddhist Psychotherapy. It addresses some questions on the relevance and the relationship of a key aspect of Buddhist understanding and prac- tice (namely the Four Brahmavihàra) to the psychotherapeutic setting and, in particular, to their role in Core Process Psychotherapy. ekamantaṃ nisinno kho asibandhakaputto gāmaṇi bhagavantaṃ etadavoca || nanu bhante | bhagavā sabbapāṇabhūtahitānukampī viharatīti || evaṃ gāmaṇi | tathāgato sabbapāṇabhūtahitānukampī viharatīti || (S iv 314) Sitting down to one side the headman Asibandhakaputto addressed the Blessed One thus: »Does the Blessed One abide in compassion and care for the welfare of all sentient beings? – »Ideed, headman, it is so. The Tathāgata abides in compassion and care for the welfare of all sentient beings.« (Saṁyutta Nikāya S 42, 7) The role of the Brahmavihàra in Core Process Psychotherapy – Akincano M. Weber 2006 – 1 – INTRODUCTION Core Process Psychotherapy is a contemplative Psychotherapy and refers explicitly to a Buddhist understanding of health and mind-development (bhàvanà). The following es- say is an attempt to understand the concept of the four Brahmavihàra, their place and function in Buddhist mind-training and to address the questions of how they inform and relate to Core Process Psychotherapy. In PART ONE the first segment of the topic will be contextualised. The teaching of the Four Brahmavihàra in their Indian background will be looked at in some detail and as- pects of the Buddhist teaching on mind-cultivation relevant to Core Process Psycho- therapy will be drawn from. In PART TWO I will be looking briefly at the Western concepts of presence, embodiment, holding environment, relational field and Source-Being-Self. -

A Buddhist Approach Based on Loving- Kindness: the Solution of the Conflict in Modern World

A BUDDHIST APPROACH BASED ON LOVING- KINDNESS: THE SOLUTION OF THE CONFLICT IN MODERN WORLD Venerable Neminda A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Buddhist Studies) Graduate School Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University C.E. 2019 A Buddhist Approach Based on Loving-kindness: The Solution of the Conflict in Modern World Venerable Neminda A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Buddhist Studies) Graduate School Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University C.E. 2019 (Copyright by Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University) Dissertation Title : A Buddhist Approach Based on Loving-Kindness: The Solution of the Conflict in Modern World Researcher : Venerable Neminda Degree : Doctor of Philosophy (Buddhist Studies) Dissertation Supervisory Committee : Phramaha Hansa Dhammahaso, Assoc. Prof. Dr., Pāḷi VI, B.A. (Philosophy), M.A. (Buddhist Studies), Ph.D. (Buddhist Studies) : Asst. Prof. Dr. Sanu Mahatthanadull, B.A. (Advertising) M.A. (Buddhist Studies), Ph.D. (Buddhist Studies) Date of Graduation : February/ 26/ 2019 Abstract The dissertation is a qualitative research. There are three objectives, namely:- 1) To explore the concept of conflict and its cause found in the Buddhist scriptures, 2) To investigate the concept of loving-kindness for solving the conflicts in suttas and the best practices applied by modern scholars 3) To present a Buddhist approach based on loving-kindness: The solution of the conflict in modern world. This finding shows the concept of conflicts and conflict resolution method in the Buddhist scriptures. The Buddhist resolution is the loving-kindness. These loving- kindness approaches provide the method, and integration theory of the Buddhist teachings, best practice of modern scholar method which is resolution method in the modern world. -

The Bodhisattva Ideal in Selected Buddhist

i THE BODHISATTVA IDEAL IN SELECTED BUDDHIST SCRIPTURES (ITS THEORETICAL & PRACTICAL EVOLUTION) YUAN Cl Thesis Submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Oriental and African Studies University of London 2004 ProQuest Number: 10672873 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10672873 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Abstract This thesis consists of seven chapters. It is designed to survey and analyse the teachings of the Bodhisattva ideal and its gradual development in selected Buddhist scriptures. The main issues relate to the evolution of the teachings of the Bodhisattva ideal. The Bodhisattva doctrine and practice are examined in six major stages. These stages correspond to the scholarly periodisation of Buddhist thought in India, namely (1) the Bodhisattva’s qualities and career in the early scriptures, (2) the debates concerning the Bodhisattva in the early schools, (3) the early Mahayana portrayal of the Bodhisattva and the acceptance of the six perfections, (4) the Bodhisattva doctrine in the earlier prajhaparamita-siltras\ (5) the Bodhisattva practices in the later prajnaparamita texts, and (6) the evolution of the six perfections (paramita) in a wide range of Mahayana texts. -

Brahmavihara Meditation & Its Potential Benefits for a Harmonious Workplace

Brahmavihara meditation & its potential benefits for a harmonious workplace Author: Jyotsna Agrawal*, Poonam Bir Kaur Sahota** *Assistant Professor (corresponding author), ** M.Phil Scholar, Department of Clinical Psychology, National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences (NIMHANS), Bangalore Email id: [email protected] Abstract: For an organization to succeed it is important to give attention to employees’ well-being. With the advent of Positive Psychology, there is empirical evidence to suggest positive experiences, and individuals leads to a profitable organization, through building personal and social resources. When it comes to application of meditation as an intervention for this purpose, research has predominantly focused upon the beneficial aspects of concentrative and mindfulness meditation. The meditative traditions have a long and rich tradition, which also includes interpersonal aspects, however research in this area trails behind. Since the vedic times, there has been an emphasis on the development of qualities called brahmavihara and in yoga tradition, Patanjali has emphasized it for overcoming a variety of difficulties. The work place interpersonal context can become a fertile ground for development of jealousy, hatred, unhealthy competitiveness etc ( Sarawasti, 2013). To counter these Brahmavihara meditation may be practiced, which includes cultivation of feelings of friendliness (Maitri), joy and goodwill (Mudita), compassion (Karuna) and acceptance and equanimity (Upeksha). These specific meditations and interventions -

Introduction to Buddhism Course Materials

INTRODUCTION TO BUDDHISM Readings and Materials Tushita Meditation Centre Dharamsala, India Tushita Meditation Centre is a member of the FPMT (Foundation for the Preservation of the Mahayana Tradition), an international network of more than 150 meditation centers and social service projects in over 40 countries under the spiritual guidance of Lama Zopa Rinpoche. More information about the FPMT can be found at: www.fpmt.org CARE OF DHARMA MATERIALS This booklet contains Dharma (teachings of the Buddha). All written materials containing Dharma teachings should be handled with respect as they contain the tools that lead to freedom and enlightenment. They should never be stepped over or placed directly on the floor or seat (where you sit or walk); a nice cloth or text table should be placed underneath them. It is best to keep all Dharma texts in a high clean place. They should be placed on the uppermost shelf of your bookcase or altar. Other objects, food, or even one’s mala should not be placed on top of Dharma texts. When traveling, Dharma texts should be packed in a way that they will not be damaged, and it is best if they are wrapped in a cloth or special Dharma book bag (available in Tushita’s library). PREPARATION OF THIS BOOKLET The material in this booklet was compiled using the ―Introductory Course Readings and Materials‖ booklet prepared by Ven. Sangye Khadro for introductory courses at Tushita, and includes several extensive excerpts from her book, How to Meditate. Ven. Tenzin Chogkyi made extensive additions and changes to this introductory course material in November 2008, while further material was added and some alterations made by Glen Svensson in July 2011, for this version. -

Sublime Abiding Places for the Heart

SUBLIME ABIDING PLACES FOR THE HEART adapted from a May 1999 workshop at Abhayagiri Buddhist Monastery with the Sati Center for Buddhist Studies THE BRAHMAVIHARAS ARE THE QUALITIES of loving-kindness, com- passion, sympathetic joy, and equanimity.What is often not sufficiently emphasized is that the brahmaviharas are fundamental to the Buddha’s teaching and practice. I shall begin with the chant called The Suffusion of the Divine Abidings.I find this chant very beautiful. It is the most frequent form in which the brahmaviharas are mentioned in the discourses of the Buddha. Here is the Divine Abidings chant: I will abide pervading one quarter with a mind imbued with loving-kindness; likewise the second, likewise the third, likewise the fourth; so above and below, around and everywhere; and to all as to myself. I will abide pervading the all-encompassing world with a mind imbued with loving-kindness; abundant, exalted, immeasurable, without hostility, and without ill will. The chant continues similarly with the other three qualities: I will abide pervading one quarter with a mind imbued with compassion.…I will abide pervading one quarter with a mind imbued with gladness.… 14 Ajahn Pasanno SUBLIME ABIDING PLACES FOR THE HEART 15 I will abide pervading one quarter with a mind equanimity. If I walk up and down, my walking is imbued with equanimity.… sublime; my standing, my sitting is sublime.This is what I mean when I say it is a sublime abiding place. Last February I was asked to be the spiritual advisor to a Thai man who was to be executed at San Quentin, and I spent the last few days So even the Buddha, a completely enlightened being, still directed until his death with him. -

An Analysis of Love Development in Buddhism(1)

Academic Services Journal Prince of Songkla University (2018), 29(1), 174-187 An Analysis of Love Development in Buddhism(1) Anchalee Piyapanyawong Department of Humanities, Faculty of Liberal Arts, Rajamongala University of Technology Thunyaburi Corresponding author [email protected] Received 19 December 2016 | Revised 25 April 2017 | Accepted 27 April 2017 | Published 1 April 2018 Abstract This article aims of analyzing an ordinary person’s way of love development in the four forms of love (Brahmavihara): Universal love (metta), compassion (karuna), sympathetic joy (mudita), and equanimity (upekkha). Buddhist thinkers propose their development in different three models, namely: 1) There is no cultivating step between the four forms of love; 2) There is a cultivating step from universal love to other three forms of love independently; and 3) There are cultivating steps from universal love to compassion, sympathetic joy, and equanimity respectively. The analysis discovered that the third model is the most possible way for an ordinary person to develop love because the other three forms of love are based on universal love and each step of development is different in its degrees of difficulty. As a result, the four forms of love develop as universal love purification. Keywords: love, universal love, compassion, sympathetic joy, equanimity, love development Introduction about by an attitude of hatred. Thus, creating love As we all know love is an influential factor in our is necessary for our happiness and the peace of the lives from the day we are born until the day we pass world as Thich Nhat Hanh (2007, p. 3), the Vietnamese away. -

Broad View, Boundless Heart.6

Broad View, Boundless Heart Broad View, Boundless Heart Ajahn Pasanno Ajahn Amaro Abhayagiri Buddhist Monastery Abhayagiri Buddhist Monastery DEDICATION 16201 Tomki Road Redwood Valley, CA 95470 We humbly dedicate the merits of this www.abhayagiri.org Dhamma offering to our beloved parents. 707-485-1630 © 2001 Abhayagiri Buddhist Monastery May all beings be released from suffering. Copyright is reserved only when reprinting for sale. Permission to reprint for free distribution is hereby given as long as no changes are made to the original. This book has been sponsored for free distribution. Cover art (“Lotus” watercolor, © 1999): Kathy Lewis, www.pacificsites.com/~gallery, email: [email protected] Photography (bhikkhu sweeping leaves, Wat Pah Nanachat,Thailand): Ping Amranand Cover and book design: Sumi Shin Text set in Bembo. Creatures of a day, what is anyone? What are they not? We are but a dream of a shadow. Yet when there comes as a gift of heaven a gleam of sunshine, there rests upon the heart a radiant light and, aye, a gentle life. Pindar (518-438 BCE) CONTENTS Key to Abbreviations 11 Sublime Abiding Places for the Heart 13 Ajahn Pasanno Illuminating the Dust: Brahmaviharas in Action 24 with Guided Meditation Ajahn Pasanno Theravada Buddhism in a Nutshell 36 Ajahn Amaro Ajahn Chah’s View of “the View” 54 Ajahn Amaro Abhayagiri Buddhist Monastery and the Authors 75 KEY TO ABBREVIATIONS A: Anguttara Nikaya M: Majjhima Nikaya S: Samyutta Nikaya SN: Sutta Nipata Ud: Udana SUBLIME ABIDING PLACES FOR THE HEART adapted from a May 1999 workshop at Abhayagiri Buddhist Monastery with the Sati Center for Buddhist Studies THE BRAHMAVIHARAS ARE THE QUALITIES of loving-kindness, com- passion, sympathetic joy, and equanimity.What is often not sufficiently emphasized is that the brahmaviharas are fundamental to the Buddha’s teaching and practice. -

The Literary Abhidhamma Text: Anuruddha's Manual of Defining Mind and Matter (Namarupapariccheda) and the Production of Pali Commentarial Literature in South India

The Literary Abhidhamma Text: Anuruddha's Manual of Defining Mind and Matter (Namarupapariccheda) and the Production of Pali Commentarial Literature in South India By Sean M. Kerr A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in South and Southeast Asian Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Alexander von Rospatt, Chair Professor Robert P. Goldman Professor Robert H. Sharf Fall 2020 ABSTRACT This dissertation is a study of the ancillary works of the well-known but little understood Pali commentator and Abhidhamma scholar, Anuruddha. Anuruddha's Manual of Defining Mind & Matter (namarupapariccheda) and Decisive Treatment of the Abhidhamma Ultimates (paramatthavinicchaya) are counted among the “sleeping texts” of the Pali commentarial tradition (texts not included in standard curricula, and therefore neglected). Anuruddha's well-studied synopsis of the subject matter of the commentarial-era Abhidhamma tradition, the Compendium of Topics of the Abhidhamma (abhidhammatthasangaha), widely known under its English title, A Comprehensive Manual of Abhidhamma, came to be regarded as the classic handbook of the orthodox Theravadin Abhidhamma system. His lesser-known works, however, curiously fell into obscurity and came to be all but forgotten. In addition to shedding new and interesting light on the Compendium of Topics of the Abhidhamma (abhidhammatthasangaha), these overlooked works reveal another side of the famous author – one as invested in the poetry of his doctrinal expositions as in the terse, unembellished clarity for which he is better remembered. Anuruddha's poetic abhidhamma treatises provide us a glimpse of a little- known early strand of Mahavihara-affiliated commentarial literature infusing the exegetical project with creative and poetic vision. -

Brahmaviharas.” Leigh Brasington’S Website: 29 Nov 2011

SD 38.5 Brahma,vihāra: The divine abodes 5 Brahma,vihāra: The divine abodes Theme: The practical cultivation of divinity in man Piya Tan ©2007, 2011 Man, one harmonious Soul of many a soul Whose nature is its own divine control Where all things flow to all, as rivers to the sea. (Percy Bysshe Shelley, Prometheus Unbound, 4.400-402. 1820) Contents (1) The significance of the divine abodes (2) The divine abodes as a set (3) Lovingkindness in practice (4) Compassion in practice (5) Gladness in practice (6) Equanimity in practice (7) Refining the divine abodes (8) Benefits of the 4 divine abodes (9) Conclusion 1 Significance of the divine abodes 1.1 THE TERM BRAHMA,VIHĀRA 1.1.1 Brahmā and brahma 1.1.1.1 The Pali term for “divine abodes” is brahma,vihāra.1 The first element, brahma, comes from the root BṚH, “to make big or strong.”2 In early Buddhism, this has nothing to do with any theistic prin- ciple but refers to the greatness or power of mental cultivation.3 Here, brahma is an adjective meaning “of or like Brahmā (the supreme God)” of the ancient Indian pantheon, and from whose mouth, the brahmins claimed, they originated. The Buddha accepts this popular and important term, but rejects its sectarian and triumphalist senses. In the early Buddhist texts, brahma (adj) refers to the supreme good, reflected in its most common commentarial gloss as “excellent, supreme, perfect” (seṭṭha).4 [1.1.1.2] Vihāra is a noun from the verb viharati, “to dwell, reside (in a place).” Here, it is used in a figurative sense, meaning “dwelling” as habitual way of life.