The Colbiana Vol. 3 No. 2 (February, 1915)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World War I Timeline C

6.2.1 World War I Timeline c June 28, 1914 Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophia are killed by Serbian nationalists. July 26, 1914 Austria declares war on Serbia. Russia, an ally of Serbia, prepares to enter the war. July 29, 1914 Austria invades Serbia. August 1, 1914 Germany declares war on Russia. August 3, 1914 Germany declares war on France. August 4, 1914 German army invades neutral Belgium on its way to attack France. Great Britain declares war on Germany. As a colony of Britain, Canada is now at war. Prime Minister Robert Borden calls for a supreme national effort to support Britain, and offers assistance. Canadians rush to enlist in the military. August 6, 1914 Austria declares war on Russia. August 12, 1914 France and Britain declare war on Austria. October 1, 1914 The first Canadian troops leave to be trained in Britain. October – November 1914 First Battle of Ypres, France. Germany fails to reach the English Channel. 1914 – 1917 The two huge armies are deadlocked along a 600-mile front of Deadlock and growing trenches in Belgium and France. For four years, there is little change. death tolls Attack after attack fails to cross enemy lines, and the toll in human lives grows rapidly. Both sides seek help from other allies. By 1917, every continent and all the oceans of the world are involved in this war. February 1915 The first Canadian soldiers land in France to fight alongside British troops. April - May 1915 The Second Battle of Ypres. Germans use poison gas and break a hole through the long line of Allied trenches. -

The London Gazette, 5 February, 1915

1252 THE LONDON GAZETTE, 5 FEBRUARY, 1915. on the 29th day of October, 1910), are, on or before died in or about the month of September, 1913), are, the 10th day of March, 1915, to send by post, pre- on or before the 9th day of March, 1915, to send by- paid, to Mr. William Edward Farr, a member of the post, prepaid;, to° Mr. H. A. "Carter, of the firm, of firm of Messrs. Booth, Wade, Farr and Lomas- Messrs. Eallowes and Carter, of 39, Bedford-row, Walker, of Leeds, the Solicitors of the defendant, London, W.C., the Solicitor of ,the defendant, Charles Mary Matilda Ingham (the wife of Henry Ingham), Daniel William Edward Brown, the executor of the the administratrix of the estate of the said Eli deceased, their Christian and surname, addresses and Dalton, deceased, their Christian and surnames, descriptions, the full parfcieuJars of their claims, a addresses and descriptions1, the full particulars of statement of (their accounts, and the mature of the their claims, a statement of their accounts, and the securities (if any) held by them, or in default thereof nature of the securities (if any) -held by them, or in they will be peremptorily excluded from it-he* benefit of default thereof they will be peremptorily excluded the said order. Every creditor holding any security is from the benefit of the said judgment. Every credi- to produce the same at the Chambers of the said tor holding any security is to produce the same at Judge, Room No. 696, Royal 'Courts of Justice, the Chambers of Mr. -

The War and Fashion

F a s h i o n , S o c i e t y , a n d t h e First World War i ii Fashion, Society, and the First World War International Perspectives E d i t e d b y M a u d e B a s s - K r u e g e r , H a y l e y E d w a r d s - D u j a r d i n , a n d S o p h i e K u r k d j i a n iii BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square, London, WC1B 3DP, UK 1385 Broadway, New York, NY 10018, USA 29 Earlsfort Terrace, Dublin 2, Ireland BLOOMSBURY, BLOOMSBURY VISUAL ARTS and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published in Great Britain 2021 Selection, editorial matter, Introduction © Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian, 2021 Individual chapters © their Authors, 2021 Maude Bass-Krueger, Hayley Edwards-Dujardin, and Sophie Kurkdjian have asserted their right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identifi ed as Editors of this work. For legal purposes the Acknowledgments on p. xiii constitute an extension of this copyright page. Cover design by Adriana Brioso Cover image: Two women wearing a Poiret military coat, c.1915. Postcard from authors’ personal collection. This work is published subject to a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial No Derivatives Licence. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher Bloomsbury Publishing Plc does not have any control over, or responsibility for, any third- party websites referred to or in this book. -

Primary Source and Background Documents D

Note: Original spelling is retained for this document and all that follow. Appendix 1: Primary source and background documents Document No. 1: Germany's Declaration of War with Russia, August 1, 1914 Presented by the German Ambassador to St. Petersburg The Imperial German Government have used every effort since the beginning of the crisis to bring about a peaceful settlement. In compliance with a wish expressed to him by His Majesty the Emperor of Russia, the German Emperor had undertaken, in concert with Great Britain, the part of mediator between the Cabinets of Vienna and St. Petersburg; but Russia, without waiting for any result, proceeded to a general mobilisation of her forces both on land and sea. In consequence of this threatening step, which was not justified by any military proceedings on the part of Germany, the German Empire was faced by a grave and imminent danger. If the German Government had failed to guard against this peril, they would have compromised the safety and the very existence of Germany. The German Government were, therefore, obliged to make representations to the Government of His Majesty the Emperor of All the Russias and to insist upon a cessation of the aforesaid military acts. Russia having refused to comply with this demand, and having shown by this refusal that her action was directed against Germany, I have the honour, on the instructions of my Government, to inform your Excellency as follows: His Majesty the Emperor, my august Sovereign, in the name of the German Empire, accepts the challenge, and considers himself at war with Russia. -

February 1915 I = A= I .The Institute I I Monthly I F = I I I ----:-- I

• 1••I lIIIIIIII1l11l11DmnllDlRm-.•••• ,llIlIIImIlllBlllBmllDDU~ ••••• Ullm:nnIUIl"I!IIIIIIIII_lIIlIIUIl!I. • i r I r February 1915 I = a= I .The Institute I I Monthly I f = I I I ----:-- I •• ~~~~~~~I~~ II vThe Institute Monthi;'1 Entered as second-class matter January 29, 1914. at the post office at Institute. West Virginia. under the Act of March 3. 1879 Devoted to the Interests of The West Virginia Colored Institute ; AT~~~~:~OL§E~~~~t; 25 Cents the Scholastic Year : : : . : 5 Cents Per Copy _··m· Contents for February J 9J 5 1915 PAGE and Lasts Six Editorials. 4 ~ ~eeks Negro Education in West Virginia. 5 Back to the Farm . 9 TWO MAIN COURSES: Buy Maine Seed Potatoes. .10 Teachers' Review and Professional. EXPENSES LOW Our Exchanges. .11 ; Special Program. .12 Junior and Senior Academics give a Creditable Program .. 12 Student Notes. .13 FOR FURTHER Around the Institute. .14 INFORMATION, WRITE HON. M. P. SHAWKEY,Charleston, W. Va. N. B. Communications for publication should be given or sent to or the Editor, or Managing Editor. All news will reach these columns through the Editors. PROF. BYRDPRILLERMAN, Institute, W. Va. EDITOR BYRD PRILLERMAN MANAGING EDITOR S. H. Guss BUSINESS MANAGER C. E. MITCHELL THE INSTITUTE MONTHLY • THE INSTITUTE MONTHLY 5 and the postal requirements. ~ Govern yourselves accordingly. ~ ~~ E HAVEBEENGENTLYCRITICIZEDBYA FEWOF THE ALUMNI, 1.111~ for not having more items of interest of what the alumni \. I are doing. ~ We depend upon you, dear alumni, in a ~ great measure, for information. Anything you send of tEbttnrtal.a interest and worth will be given space. Be a critic, but be a construct- ive one. -

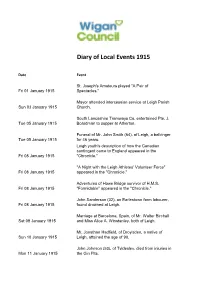

Diary of Local Events 1915

Diary of Local Events 1915 Date Event St. Joseph's Amateurs played "A Pair of Fri 01 January 1915 Spectacles." Mayor attended intercession service at Leigh Parish Sun 03 January 1915 Church. South Lancashire Tramways Co. entertained Pte. J. Tue 05 January 1915 Boardman to supper at Atherton. Funeral of Mr. John Smith (64), of Leigh, a bellringer Tue 05 January 1915 for 46 years. Leigh youth's description of how the Canadian contingent came to England appeared in the Fri 08 January 1915 "Chronicle." "A Night with the Leigh Athletes' Volunteer Force" Fri 08 January 1915 appeared in the "Chronicle." Adventures of Howe Bridge survivor of H.M.S. Fri 08 January 1915 "Formidable" appeared in the "Chronicle." John Sanderson (32), an Earlestown farm labourer, Fri 08 January 1915 found drowned at Leigh. Marriage at Barcelona, Spain, of Mr. Walter Birchall Sat 09 January 1915 and Miss Alice A. Winstanley, both of Leigh. Mr. Jonathan Hadfield, of Droylsden, a native of Sun 10 January 1915 Leigh, attained the age of 90. John Johnson (53), of Tyldesley, died from injuries in Mon 11 January 1915 the Gin Pits. Leigh Town Council: The Distress Committee Tue 12 January 1915 criticised. Tyldesley and District Feather Society's annual Tue 12 January 1915 meeting. Soldiers and Belgians entertained to tea and concert Wed 13 January 1915 at Formby Hall, Atherton. Funeral of Mr. Thomas Prescott (49), of Schofield- Fri 15 January 1915 street, Leigh, warehouseman at Victoria mills. Mawdsley pension of 5s.a week awarded to Mr. Sat 16 January 1915 Robert Radcliffe (76), a Bedford spinner. -

Special Libraries, February 1915 Special Libraries Association

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Special Libraries, 1915 Special Libraries, 1910s 2-1-1915 Special Libraries, February 1915 Special Libraries Association Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sla_sl_1915 Part of the Cataloging and Metadata Commons, Collection Development and Management Commons, Information Literacy Commons, and the Scholarly Communication Commons Recommended Citation Special Libraries Association, "Special Libraries, February 1915" (1915). Special Libraries, 1915. Book 2. http://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sla_sl_1915/2 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Libraries, 1910s at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Special Libraries, 1915 by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Special Libraries PUBLISHED BY THE EXECUTIVE BOARD SPECIAL LIBRARIES ASSOCIATION Montllls exccpt July al~dAugust President, Vlce-Prcsldcnt, Secretary-Treasurer, Ec11Lorlal nnd 1'11hlIcal1on Omce, Indiana Bureau Cl~iranceB. Lester, Wisconsin Legislative Ref- of Leglslallve Ii~formntion,lndlanapol~s, Ind. elence Library ; hInrlan R. Glenn, Amerlcnn 3uhscrlptlnns, 03 nload alrect, Bouton. Mass Rankers' Associatwn, Ncw Yorlc Clty. Entercd nt the Puatufflce at Ir~dlanapol~s,Ind, hItknamng IEdltor of Spccial L~brar~es.-John A. as second-class mat ler. Ln~p,Bureau of Leglslnt~veInformallon. In- Subscription.. ... .52.00 a year (10 numbers) dlanapolls, Ind. Single copies .....................25 cents- hwstant IEdltor. Rtl~elClclancl, Eureuu of Leg- PresldcnL .................... .ll 1-1. Johr~ston Islat~veInfor~natlon, Indian:ipol~s, Ind. pzau of Rail way Eco~iomics, \Yashlng ton, U. G. Vice-Pl'esldent .......... .E!~znbeth V. Dobbins Arnerican 'hlcpl10tlc nnd lclegrngh Co., New P N. -

Rice Family Correspondence

TITLE: Rice family correspondence DATE RANGE: 1912-1919 CALL NUMBER: MS 0974 PHYSICAL DESCRIPTION: 2 linear ft. (4 boxes) PROVENANCE: Donated by Hester Rice Clark and Sylvia Rice Hilsinger on May 13, 1980. COPYRIGHT: The Arizona Historical Society owns the copyright to this collection. RESTRICTIONS: This collection is unrestricted. CREDIT LINE: Rice family correspondence, MS 0974, Arizona Historical Society-Tucson PROCESSED BY: Finding aid transcribed by Nancy Siner, November 2015 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE: Harvey Clifton Rice was born in Liberal, Kansas on September 1, 1889, to Katherine Lane Rice and Joseph Davenport Rice. He lived with his parents and sister, Sarah, in Tecumseh, Kansas until 1914, when the family moved to Hayden, Arizona. Harvey and his father were employed by the Ray Consolidated Copper Company. Sarah worked as a telephone operator until she married and moved to Humboldt, Arizona in 1916. In Hayden, the Rice family lived in a tent to which they later added rooms. Harvey Rice was drafted into the United States Army in 1917. He was plagued by poor health during his term of service and was discharged on July 27, 1919. Charlotte Abigail Burre was born in Independence, Missouri on December 11, 1888. Her parents, Henry Burre and Mary Catherine Sappenfield Burre, had five other daughters: Hester, Lucy, Henrietta, Martha and George; and three sons: Robert, Carrol and Ed. Charlotte’s father was a carpenter and the family supplemented his income by taking boarders in the home. Charlotte’s brother, Carrol, was drafted and served in France where he was awarded the distinguished Served Cross and the Croix de Guerre. -

Lance Corporal Adolf Hitler on the Western Front, 1914-1918 Charles Bracelen Flood

The Kentucky Review Volume 5 | Number 3 Article 2 1985 Lance Corporal Adolf Hitler on the Western Front, 1914-1918 Charles Bracelen Flood Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/kentucky-review Part of the European History Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Flood, Charles Bracelen (1985) "Lance Corporal Adolf Hitler on the Western Front, 1914-1918," The Kentucky Review: Vol. 5 : No. 3 , Article 2. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/kentucky-review/vol5/iss3/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Kentucky Libraries at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Kentucky Review by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lance Corporal Adolf Hitler on the Western Front, 1914-1918 Charles Bracelen Flood The following is excerpted from the forthcoming Hitler to Power, to be published by Houghton Mifflin. The book traces Hitler's early life, with emphasis upon his experiences during the First World War, before detailing his activities from 1919, when he entered political life, until 30 January 1933, when he became chancellor of Germany. The pages immediately before this excerpt deal with his prewar existence in Vienna, during which he lived in public institutions for homeless men while eking out a living as a painter of postcards and illustrations used by framemakers who found that their frames sold more readily when there were pictures in them. -

The Gallipoli Campaign Learning from a Mismatch of Strategic Ends and Means

British battleship HMS Irresistible abandoned and sinking, having been shattered by explosion of floating mine in Dardanelles during attack on Narrows’ Forts, March 18, 1915 (Royal Navy/Library of Congress) The Gallipoli Campaign Learning from a Mismatch of Strategic Ends and Means By Raymond Adams orld War I began on July 28, and relatively inexpensive in terms of tactics in response to new, highly de- 1914, 1 month after the assas- blood and treasure. Almost immediately, structive weapons, resulting in massive Wsination of Archduke Franz however, the combatants faced each other casualties. Rising calls from British po- Ferdinand, heir-apparent to the Austro- in a long line of static defensive trenches. litical leaders, the media, and the public Hungarian throne.1 Most Europeans The Western Front quickly became a demanded action to break the stalemate. expected the conflict to be short—“over killing ground of unprecedented violence British strategists responded by opening by Christmas” was a common refrain— in human history: combined British, a new front in the east with two strategic French, and German casualties totaled objectives: drive Turkey out of the war 2,057,621 by January 1915.2 by attacking Constantinople, and open 3 Lieutenant Colonel Raymond Adams, USMCR, is a The character of war had changed. a route to beleaguered ally Russia. The student at the National War College. Armies had not changed their battlefield decision to open a second front in the 96 Recall / The Gallipoli Campaign JFQ 79, 4th Quarter 2015 east in 1915 ultimately failed to achieve military officers to plan for the seizure Flawed Assumptions Britain’s strategic objectives during the of the Gallipoli Peninsula, “with a view Underpinning the first full year of World War I. -

Great War Centenary 19 14-19 18 201 4-2018

HEDDLU DE CYMRU • SOUTH WALES POLICE THE GREAT WAR CENTENARY 19 14-19 18 201 4-2018 LED BY IWM LEST WE FORGET REMEMBERED WITH PRIDE IN 2 01 5 THOSE WHO DIED IN 191 5 LEARN • ENGAG1 E • REMEMBER THE GREAT WAR CENTENARY • 191 5 INTRODUCTION 1915 marked the first full year of the were wounded. This arises in the First World War. As will be seen context of our families, our from the summary of the year which communities and policing. Second, is appears in this booklet, it saw a the impact which the War had on our number of attempts by the Allies to world: its effects are still resonating break the deadlock of trench warfare down the years to our own day, which had developed on the Western particularly in the Front, including the costly Battle of Middle East. Loos when several police officers Last year we marked the centenary from our predecessor forces were of the commencement of the war killed, including six on the same day - with a booklet which sought to 27th September. provide some context and It was also a year which saw the background and details of those who Allies attempt to force Turkey out of had died during 1914. It has been the war resulting in the terrible very well received and many copies fighting and loss of life on the have been distributed to individuals, Gallipoli peninsula where a including relatives of some of those Glamorgan police officer lost his life. who died, and organisations. At the Second Battle of Ypres the Germans used poison gas on the In this year’s booklet, in addition to Western Front for the first time and profiles of those who died, we have the British responded in kind at the other sections which we hope will be Battle of Loos. -

Eggs for the Wounded’: a Study of Contributions to the National Egg Collection in West Sussex

West Sussex & the Great War Project www.westsussexpast.org.uk ‘Eggs for the Wounded’: A Study of Contributions to the National Egg Collection in West Sussex (www.loc.gov/pictures/related/?fi=subject=chickens. England 1910-1920. No known restrictions on publication.) http://www.ww1propoganderposters/ [1] By Maria Fryday 1 Maria Fryday and West Sussex County Council West Sussex & the Great War Project www.westsussexpast.org.uk Introduction: I first became intrigued by reports on ‘Eggs for the Wounded’ whilst researching some information with regard to my maternal grandparents Fanny Ethel Foskett and William Sydney Manning, who served with the Royal Sussex Regiment, and later, from 1916, with the 2/6th Battalion, Royal Warwickshire, The Royal Regiment of Fusiliers. They had apparently married during my late grandfather’s leave in October 1917, and I decided to review the local newspaper to see if, remotely, their marriage had been reported. It was not. However, weekly records of egg collections for the southern West Sussex area were noted with some pomp, and so began a trawl of reports on these items. West Sussex County Council were evidently interested in such information to collect to supplement the forthcoming documentation of information relating to persons and issues concerned with West Sussex during World War 1 (WW1) also referred to as The Great War, and so I continued to research my unintentional project, concentrating on local – for me - information detailed within the Chichester Observer and West Sussex Recorder. I had no expectation when started to research this topic that I would write to such length, nor that the Reference List at the end would become so extensive… So, a shortened version will be provided as well, to make it less challenging to read.