Lance Corporal Adolf Hitler on the Western Front, 1914-1918 Charles Bracelen Flood

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fitzgerald in the Late 1910S: War and Women Richard M

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Duquesne University: Digital Commons Duquesne University Duquesne Scholarship Collection Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2009 Fitzgerald in the Late 1910s: War and Women Richard M. Clark Follow this and additional works at: https://dsc.duq.edu/etd Recommended Citation Clark, R. (2009). Fitzgerald in the Late 1910s: War and Women (Doctoral dissertation, Duquesne University). Retrieved from https://dsc.duq.edu/etd/416 This Immediate Access is brought to you for free and open access by Duquesne Scholarship Collection. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Duquesne Scholarship Collection. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FITZGERALD IN THE LATE 1910s: WAR AND WOMEN A Dissertation Submitted to the McAnulty College and Graduate School Duquesne University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Richard M. Clark August 2009 Copyright by Richard M. Clark 2009 FITZGERALD IN THE LATE 1910s: WAR AND WOMEN By Richard M. Clark Approved July 21, 2009 ________________________________ ________________________________ Linda Kinnahan, Ph.D. Greg Barnhisel, Ph.D. Professor of English Assistant Professor of English (Dissertation Director) (2nd Reader) ________________________________ ________________________________ Frederick Newberry, Ph.D. Magali Cornier Michael, Ph.D. Professor of English Professor of English (1st Reader) (Chair, Department of English) ________________________________ Christopher M. Duncan, Ph.D. Dean, McAnulty College and Graduate School of Liberal Arts iii ABSTRACT FITZGERALD IN THE LATE 1910s: WAR AND WOMEN By Richard M. Clark August 2009 Dissertation supervised by Professor Linda Kinnahan This dissertation analyzes historical and cultural factors that influenced F. -

December 1914

News from the Front December 1914 been given a commission, worked to within 50 yards, and commences training at nearly up to our barbed wire High Wycombe shortly; entanglements. This is not a whilst their eldest daughter, critical position, as where the Kathleen, has been appointed rest of the line moves senior assistant at the forward we will be able to Military Hospital in do so, but no advantage will Felixstowe.” be gained by moving 19th December 1914 independently. North-Eastern Daily Gazette The Germans say in the papers that Ypres is untouched, but this is not CHRISTMAS POST true. A large number of the “The Post Office notifies that houses are blown to pieces, Christmas parcels for the and it is still being shelled. Expeditionary Force must not The Cathedral has had exceed seven pounds in several shells through the weight, and must not be roof. There is little change posted later than the 12th here, and this battle looks December. Letters should not like lasting longer.” th be later than the 14 5th December 1914 December.” Stockton & Thornaby Herald th greatest wars in history. 5 December 1914 A STOCKTON APPEAL “Mr R. Tyson Hodgson, The coming Christmas to Stockton & Thornaby Herald CHRISTMAS PLUM honourable secretary of the the wives, families, and PUDDING RECIPE Stockton branch of the Soldiers’ widowed mothers will lack QUIETNESS AT THE “Take three-quarters of a and Sailors’ Families’ much of its cheerfulness on FRONT pound of flour, two heaped- Association makes the following account of the absence of many “A Billingham Trooper in the up teaspoonfuls of appeal on behalf of the wives, that are dear to them, and the Northumberland Hussars, Borwick’s Baking Powder, families and widows of soldiers anxious circumstances in which writing from the front, refers two ounces of breadcrumbs, and sailors in Stockton and they are placed. -

Lance Corporal Peter Conacher Died

Name: Peter Conacher Position: Lance Corporal DOB-DOD: 1919- 9 September 1943 Peter Conacher, Lance Corporal for the Royal Signals 231st Brigade, British Army, died during the period of Allied invasion of the Italian mainland. The Allied invasion of Sicily was to be the first of three amphibious assault landings conducted by the 231st Brigade during the war. The brigade was constituted as an independent brigade group under the command of Brigadier Roy Urquhart (later famous as commander of the 1st Airborne Division which was destroyed at Arnhem in September 1944). After some hard fighting, including the 2nd Devons at Regalbuto amongst the foothills of Mount Etna, the Germans were driven from Sicily and the Allies prepared to invade Italy. The 231st Brigade's second assault landing was at Porto San Venere on 7 September 1943, when the Allies invaded Italy. They were now experienced amphibious assault troops, however during this period Lance Corporal Peter Conacher died. After the September assault, the 231st Brigade became an integral part of the veteran 50th (Northumbrian) Infantry Division and was recalled to England with the division, to prepare for the Allied invasion of Normandy, scheduled for the spring of 1944. In February 1944 Brigadier Sir A.B.G. Stanier assumed command of the brigade. Peter was remembered by his parents Hugh and Marion Conacher of Dundee. He is buried in Salerno War Cemetery and his name is also recorded on a memorial situated in Dundee Telephone Hse having joined PO Engineering in March 1942. His parents provided a very touching and deeply moving inscription in memory of their son “THOUGH ABSENT HE IS EVER NEAR STILL MISSED, STILL LOVED EVER DEAR”. -

Special Libraries, December 1914 Special Libraries Association

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Special Libraries, 1914 Special Libraries, 1910s 12-1-1914 Special Libraries, December 1914 Special Libraries Association Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sla_sl_1914 Part of the Cataloging and Metadata Commons, Collection Development and Management Commons, Information Literacy Commons, and the Scholarly Communication Commons Recommended Citation Special Libraries Association, "Special Libraries, December 1914" (1914). Special Libraries, 1914. Book 10. http://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sla_sl_1914/10 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Libraries, 1910s at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Special Libraries, 1914 by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Special Libraries a - Vol. 5 DEORMBER, 1014 No. 1 0 - -- ---- PUBLISHED BY THE EXECUTIVX BOARD SPECIAL LIBRARIES ASSOCIATION Prcs~dent, V~ce-Preslclent, Secrclary-Tret~surer, Monthly except July and August Edltorlai and Publ~calionOfice Indiana BilTenu Clnr~nceR. Leslcr, \VisconsIn Lcfilslatlve Ref- oC Leg-lnlatlve Informat~on,~n~lanapolls, Ind. erence L~brary; Marian R. Glenn, Amerlckm Subscrlgt~ons, 93 BronA street, Boston, Mass. Uanlrers' Ashoc~aLlon, New Yorlc Clly. Zntered at the Postomce at Ind~nnapohs,Ind., Manng~ngEditor of Spec~alLil.warles .-.fohn A. as second-clash matter. Lapp, Bureau of Lcglslatlve InCormn'tlon, In- Subscription. .....$2.00 a year (10 numbers) dianapolis, Ind. Single copies .....................25 cents Assishnt Editor, Ethel Clelnntl, Burcil~~of Lop- Presl(1enL . .............li 13. Johnston lslatlvc Inlor1iiallon, lndlnnapolls, Ind. Bur_eau of" i7:aliway ~conornlcs,WashinpLon, -U. C Vice-Prcsideut ...........ElIrabetti V. DobMns American Telephone and Tclegrngll Co., NOW I?. -

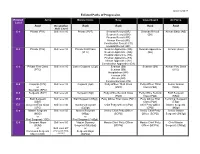

Enlisted Paths of Progression Chart

Updated 2/24/17 Enlisted Paths of Progression Enlisted Army Marine Corps Navy Coast Guard Air Force Level Rank Occupation Rank Rank Rank Rank Skill Level E-1 Private (PV1) Skill level 10 Private (PVT) Seaman Recruit (SR) Seaman Recruit Airman Basic (AB) Seaman Recruit (SR) (SR) Fireman Recruit (FR) Airman Recruit (AR) Construction Recruit (CR) Hospital Recruit (HR) E-2 Private (PV2) Skill level 10 Private First Class Seaman Apprentice (SA) Seaman Apprentice Airman (Amn) (PFC) Seaman Apprentice (SA) (SA) Hospital Apprentice (HA) Fireman Apprentice (FA) Airman Apprentice (AA) Construction Apprentice (CA) E-3 Private First Class Skill level 10 Lance Corporal (LCpl) Seaman (SN) Seaman (SN) Airman First Class (PFC) Seaman (SN) (A1C) Hospitalman (HN) Fireman (FN) Airman (AN) Constructionman (CN) E-4 Corporal (CPL) Skill level 10 Corporal (Cpl) Petty Officer Third Class Petty Officer Third Senior Airman or (PO3) Class (PO3) (SRA) Specialist (SPC) E-5 Sergeant (SGT) Skill level 20 Sergeant (Sgt) Petty Office Second Class Petty Office Second Staff Sergeant (PO2) Class (PO2) (SSgt) E-6 Staff Sergeant Skill level 30 Staff Sergeant (SSgt) Petty Officer First Class (PO1) Petty Officer First Technical Sergeant (SSG) Class (PO1) (TSgt) E-7 Sergeant First Class Skill level 40 Gunnery Sergeant Chief Petty Officer (CPO) Chief Petty Officer Master Sergeant (SFC) (GySgt) (CPO) (MSgt) E-8 Master Sergeant Skill level 50 Master Sergeant Senior Chief Petty Officer Senior Chief Petty Senior Master (MSG) (MSgt) (SCPO) Officer (SCPO) Sergeant (SMSgt) or or First Sergeant (1SG) First Sergeant (1stSgt) E-9 Sergeant Major Skill level 50 Master Gunnery Master Chief Petty Officer Master Chief Petty Chief Master (SGM) Sergeant (MGySgt) (MCPO) Officer (MCPO) Sergeant (CMSgt) or Skill level 60* or Command Sergeant (*For some fields, Sergeant Major Major (CSM) not all.) (SgtMaj) . -

Leigh Chronicle," for This Week Only Four Pages, Fri 21 August 1914 Owing to Threatened Paper Famine

Diary of Local Events 1914 Date Event England declared war on Germany at 11 p.m. Railways taken over by the Government; Territorials Tue 04 August 1914 mobilised. Jubilee of the Rev. Father Unsworth, of Leigh: Presentation of illuminated address, canteen of Tue 04 August 1914 cutlery, purse containing £160, clock and vases. Leigh and Atherton Territorials mobilised at their respective drill halls: Leigh streets crowded with Wed 05 August 1914 people discussing the war. Accidental death of Mr. James Morris, formerly of Lowton, and formerly chief pay clerk at Plank-lane Wed 05 August 1914 Collieries. Leigh and Atherton Territorials leave for Wigan: Mayor of Leigh addressed the 124 Leigh Territorials Fri 07 August 1914 in front of the Town Hall. Sudden death of Mr. Hugh Jones (50), furniture Fri 07 August 1914 dealer, of Leigh. Mrs. J. Hartley invited Leigh Women's Unionist Association to a garden party at Brook House, Sat 08 August 1914 Glazebury. Sat 08 August 1914 Wingate's Band gave recital at Atherton. Special honour conferred by Leigh Buffaloes upon Sun 09 August 1914 Bro. R. Frost prior to his going to the war. Several Leigh mills stopped for all week owing to Mon 10 August 1914 the war; others on short time. Mon 10 August 1914 Nearly 300 attended ambulance class at Leigh. Leigh Town Council form Committee to deal with Tue 11 August 1914 distress. Death of Mr. T. Smith (77), of Schofield-street, Wed 12 August 1914 Leigh, the oldest member of Christ Church. Meeting of Leigh War Distress Committee at the Thu 13 August 1914 Town Hall. -

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945. T939. 311 rolls. (~A complete list of rolls has been added.) Roll Volumes Dates 1 1-3 January-June, 1910 2 4-5 July-October, 1910 3 6-7 November, 1910-February, 1911 4 8-9 March-June, 1911 5 10-11 July-October, 1911 6 12-13 November, 1911-February, 1912 7 14-15 March-June, 1912 8 16-17 July-October, 1912 9 18-19 November, 1912-February, 1913 10 20-21 March-June, 1913 11 22-23 July-October, 1913 12 24-25 November, 1913-February, 1914 13 26 March-April, 1914 14 27 May-June, 1914 15 28-29 July-October, 1914 16 30-31 November, 1914-February, 1915 17 32 March-April, 1915 18 33 May-June, 1915 19 34-35 July-October, 1915 20 36-37 November, 1915-February, 1916 21 38-39 March-June, 1916 22 40-41 July-October, 1916 23 42-43 November, 1916-February, 1917 24 44 March-April, 1917 25 45 May-June, 1917 26 46 July-August, 1917 27 47 September-October, 1917 28 48 November-December, 1917 29 49-50 Jan. 1-Mar. 15, 1918 30 51-53 Mar. 16-Apr. 30, 1918 31 56-59 June 1-Aug. 15, 1918 32 60-64 Aug. 16-0ct. 31, 1918 33 65-69 Nov. 1', 1918-Jan. 15, 1919 34 70-73 Jan. 16-Mar. 31, 1919 35 74-77 April-May, 1919 36 78-79 June-July, 1919 37 80-81 August-September, 1919 38 82-83 October-November, 1919 39 84-85 December, 1919-January, 1920 40 86-87 February-March, 1920 41 88-89 April-May, 1920 42 90 June, 1920 43 91 July, 1920 44 92 August, 1920 45 93 September, 1920 46 94 October, 1920 47 95-96 November, 1920 48 97-98 December, 1920 49 99-100 Jan. -

World War I Timeline C

6.2.1 World War I Timeline c June 28, 1914 Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife Sophia are killed by Serbian nationalists. July 26, 1914 Austria declares war on Serbia. Russia, an ally of Serbia, prepares to enter the war. July 29, 1914 Austria invades Serbia. August 1, 1914 Germany declares war on Russia. August 3, 1914 Germany declares war on France. August 4, 1914 German army invades neutral Belgium on its way to attack France. Great Britain declares war on Germany. As a colony of Britain, Canada is now at war. Prime Minister Robert Borden calls for a supreme national effort to support Britain, and offers assistance. Canadians rush to enlist in the military. August 6, 1914 Austria declares war on Russia. August 12, 1914 France and Britain declare war on Austria. October 1, 1914 The first Canadian troops leave to be trained in Britain. October – November 1914 First Battle of Ypres, France. Germany fails to reach the English Channel. 1914 – 1917 The two huge armies are deadlocked along a 600-mile front of Deadlock and growing trenches in Belgium and France. For four years, there is little change. death tolls Attack after attack fails to cross enemy lines, and the toll in human lives grows rapidly. Both sides seek help from other allies. By 1917, every continent and all the oceans of the world are involved in this war. February 1915 The first Canadian soldiers land in France to fight alongside British troops. April - May 1915 The Second Battle of Ypres. Germans use poison gas and break a hole through the long line of Allied trenches. -

Guides to German Records Microfilmed at Alexandria, Va

GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA. No. 32. Records of the Reich Leader of the SS and Chief of the German Police (Part I) The National Archives National Archives and Records Service General Services Administration Washington: 1961 This finding aid has been prepared by the National Archives as part of its program of facilitating the use of records in its custody. The microfilm described in this guide may be consulted at the National Archives, where it is identified as RG 242, Microfilm Publication T175. To order microfilm, write to the Publications Sales Branch (NEPS), National Archives and Records Service (GSA), Washington, DC 20408. Some of the papers reproduced on the microfilm referred to in this and other guides of the same series may have been of private origin. The fact of their seizure is not believed to divest their original owners of any literary property rights in them. Anyone, therefore, who publishes them in whole or in part without permission of their authors may be held liable for infringement of such literary property rights. Library of Congress Catalog Card No. 58-9982 AMERICA! HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION COMMITTEE fOR THE STUDY OP WAR DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECOBDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXAM)RIA, VA. No* 32» Records of the Reich Leader of the SS aad Chief of the German Police (HeiehsMhrer SS und Chef der Deutschen Polizei) 1) THE AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION (AHA) COMMITTEE FOR THE STUDY OF WAE DOCUMENTS GUIDES TO GERMAN RECORDS MICROFILMED AT ALEXANDRIA, VA* This is part of a series of Guides prepared -

Woodrow Wilson's Ideological War: American Intervention in Russia

Best Integrated Writing Volume 2 Article 9 2015 Woodrow Wilson’s Ideological War: American Intervention in Russia, 1918-1920 Shane Hapner Wright State University Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/biw Part of the American Literature Commons, Ancient, Medieval, Renaissance and Baroque Art and Architecture Commons, Applied Behavior Analysis Commons, Business Commons, Classical Archaeology and Art History Commons, Comparative Literature Commons, English Language and Literature Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, International and Area Studies Commons, Medicine and Health Sciences Commons, Modern Literature Commons, Nutrition Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, Religion Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hapner, S. (2015). Woodrow Wilson’s Ideological War: American Intervention in Russia, 1918-1920, Best Integrated Writing, 2. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Best Integrated Writing by an authorized editor of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact library- [email protected]. SHANE HAPNER HST 4220 Best Integrated Writing: Journal of Excellence in Integrated Writing Courses at Wright State Fall 2015 (Volume 2) Article #8 Woodrow Wilson’s Ideological War: American Intervention in Russia, 1918-1920 SHANE HAPNER HST 4220-01: Soviet Union Spring 2014 Dr. Sean Pollock Dr. Pollock notes that having carefully examined an impressive array of primary and secondary sources, Shane demonstrates in forceful, elegant prose that American intervention in the Russian civil war was consonant with Woodrow Wilson’s principle of self- determination. Thanks to the sophistication and cogency of the argument, and the clarity of the prose, the reader forgets that the paper is the work of an undergraduate. -

Interaction and Perception in Anglo-German Armies: 1689-1815

Interaction and Perception in Anglo-German Armies: 1689-1815 Mark Wishon Ph.D. Thesis, 2011 Department of History University College London Gower Street London 1 I, Mark Wishon confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 ABSTRACT Throughout the ‘long eighteenth century’ Britain was heavily reliant upon soldiers from states within the Holy Roman Empire to augment British forces during times of war, especially in the repeated conflicts with Bourbon, Revolutionary, and Napoleonic France. The disparity in populations between these two rival powers, and the British public’s reluctance to maintain a large standing army, made this external source of manpower of crucial importance. Whereas the majority of these forces were acting in the capacity of allies, ‘auxiliary’ forces were hired as well, and from the mid-century onwards, a small but steadily increasing number of German men would serve within British regiments or distinct formations referred to as ‘Foreign Corps’. Employing or allying with these troops would result in these Anglo- German armies operating not only on the European continent but in the American Colonies, Caribbean and within the British Isles as well. Within these multinational coalitions, soldiers would encounter and interact with one another in a variety of professional and informal venues, and many participants recorded their opinions of these foreign ‘brother-soldiers’ in journals, private correspondence, or memoirs. These commentaries are an invaluable source for understanding how individual Briton’s viewed some of their most valued and consistent allies – discussions that are just as insightful as comparisons made with their French enemies. -

Commander's Guide to German Society, Customs, and Protocol

Headquarters Army in Europe United States Army, Europe, and Seventh Army Pamphlet 360-6* United States Army Installation Management Agency Europe Region Office Heidelberg, Germany 20 September 2005 Public Affairs Commanders Guide to German Society, Customs, and Protocol *This pamphlet supersedes USAREUR Pamphlet 360-6, 8 March 2000. For the CG, USAREUR/7A: E. PEARSON Colonel, GS Deputy Chief of Staff Official: GARY C. MILLER Regional Chief Information Officer - Europe Summary. This pamphlet should be used as a guide for commanders new to Germany. It provides basic information concerning German society and customs. Applicability. This pamphlet applies primarily to commanders serving their first tour in Germany. It also applies to public affairs officers and protocol officers. Forms. AE and higher-level forms are available through the Army in Europe Publishing System (AEPUBS). Records Management. Records created as a result of processes prescribed by this publication must be identified, maintained, and disposed of according to AR 25-400-2. Record titles and descriptions are available on the Army Records Information Management System website at https://www.arims.army.mil. Suggested Improvements. The proponent of this pamphlet is the Office of the Chief, Public Affairs, HQ USAREUR/7A (AEAPA-CI, DSN 370-6447). Users may suggest improvements to this pamphlet by sending DA Form 2028 to the Office of the Chief, Public Affairs, HQ USAREUR/7A (AEAPA-CI), Unit 29351, APO AE 09014-9351. Distribution. B (AEPUBS) (Germany only). 1 AE Pam 360-6 ● 20 Sep 05 CONTENTS Section I INTRODUCTION 1. Purpose 2. References 3. Explanation of Abbreviations 4. General Section II GETTING STARTED 5.