{Replace with the Title of Your Dissertation}

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

News Pdf 311.Pdf

2013 World Baseball Classic- The Nominated Players of Team Japan(Dec.3,2012) *ICC-Intercontinental Cup,BWC-World Cup,BAC-Asian Championship Year&Status( A-Amateur,P-Professional) *CL-NPB Central League,PL-NPB Pacific League World(IBAF,Olympic,WBC) Asia(BFA,Asian Games) Other(FISU.Haarlem) 12 Pos. Name Team Alma mater in Amateur Baseball TB D.O.B Asian Note Haarlem 18U ICC BWC Olympic WBC 18U BAC Games FISU CUB- JPN P 杉内 俊哉 Toshiya Sugiuchi Yomiuri Giants JABA Mitsubishi H.I. Nagasaki LL 1980.10.30 00A,08P 06P,09P 98A 01A 12 Most SO in CL P 内海 哲也 Tetsuya Utsumi Yomiuri Giants JABA Tokyo Gas LL 1982.4.29 02A 09P 12 Most Win in CL P 山口 鉄也 Tetsuya Yamaguchi Yomiuri Giants JHBF Yokohama Commercial H.S LL 1983.11.11 09P ○ 12 Best Holder in CL P 澤村 拓一 Takuichi Sawamura Yomiuri Giants JUBF Chuo University RR 1988.4.3 10A ○ P 山井 大介 Daisuke Yamai Chunichi Dragons JABA Kawai Musical Instruments RR 1978.5.10 P 吉見 一起 Kazuki Yoshimi Chunichi Dragons JABA TOYOTA RR 1984.9.19 P 浅尾 拓也 Takuya Asao Chunichi Dragons JUBF Nihon Fukushi Univ. RR 1984.10.22 P 前田 健太 Kenta Maeda Hiroshima Toyo Carp JHBF PL Gakuen High School RR 1988.4.11 12 Best ERA in CL P 今村 猛 Takeshi Imamura Hiroshima Toyo Carp JHBF Seihou High School RR 1991.4.17 ○ P 能見 篤史 Atsushi Nomi Hanshin Tigers JABA Osaka Gas LL 1979.5.28 04A 12 Most SO in CL P 牧田 和久 Kazuhisa Makita Seibu Lions JABA Nippon Express RR 1984.11.10 P 涌井 秀章 Hideaki Wakui Seibu Lions JHBF Yokohama High School RR 1986.6.21 04A 08P 09P 07P ○ P 攝津 正 Tadashi Settu Fukuoka Softbank Hawks JABA Japan Railway East-Sendai RR 1982.6.1 07A 07BWC Best RHP,12 NPB Pitcher of the Year,Most Win in PL P 大隣 憲司 Kenji Otonari Fukuoka Softbank Hawks JUBF Kinki University LL 1984.11.19 06A ○ P 森福 允彦 Mitsuhiko Morifuku Fukuoka Softbank Hawks JABA Shidax LL 1986.7.29 06A 06A ○ P 田中 将大 Masahiro Tanaka Tohoku Rakuten Golden Eagles JHBF Tomakomai H.S.of Komazawa Univ. -

Feelin' Casual! Feelin' Casual!

Feelin’ casual! Feelin’ casual! to SENDAI to YAMAGATA NIIGATA Very close to Aizukougen Mt. Chausu NIIGATA TOKYO . Very convenient I.C. Tohoku Expressway Only 50minutes by to NIKKO and Nasu Nasu FUKUSHIMA other locations... I.C. SHINKANSEN. JR Tohoku Line(Utsunomiya Line) Banetsu Utsunomiya is Kuroiso Expressway FUKUSHIMA AIR PORT Yunishigawa KORIYAMA your gateway to Tochigi JCT. Yagan tetsudo Line Shiobara Nasu Nishinasuno- shiobara shiobara I.C. Nishi- nasuno Tohoku Shinkansen- Kawaji Kurobane TOBU Utsunomiya Line Okukinu Kawamata 3 UTSUNO- UTSUNOMIYA MIYA I.C. Whole line opening Mt. Nantai Kinugawa Jyoutsu Shinkansen Line to traffic schedule in March,2011 Nikko KANUMA Tobu Bato I.C. Utsunomiya UTSUNOMIYA 2 to NAGANO TOCHIGI Line TOCHIGI Imaichi TSUGA Tohoku Shinkansen Line TAKA- JCT. MIBU USTUNOMIYA 6 SAKI KAMINOKAWA 1 Nagono JCT. IWAFUNE I.C. 1 Utsunomiya → Nikko JCT. Kitakanto I.C. Karasu Shinkansen Expressway yama Line HITACHI Ashio NAKAMINATO JR Nikko Line Utsunomiya Tohoku Shinkansen- I.C. I.C. TAKASAKI SHIN- Utsunomiya Line TOCHIGI Kanuma Utsunomiya Tobu Nikko Line IBARAKI AIR PORT Tobu Motegi KAWAGUCHI Nikko, where both Japanese and international travelers visit, is Utsuno- 5 JCT. miya MISATO OMIYA an international sightseeing spot with many exciting spots to TOCHIGI I.C. see. From Utsunomiya, you can enjoy passing through Cherry Tokyo blossom tunnels or a row of cedar trees on Nikko Highway. Utsunomiya Mashiko Tochigi Kaminokawa NERIMA Metropolitan Mibu I.C. Moka I.C. Expressway Tsuga I.C. SAPPORO JCT. Moka Kitakanto Expressway UENO Nishikiryu I.C. ASAKUSA JR Ryomo Line Tochigi TOKYO Iwafune I.C. Kasama 2 Utsunomiya → Kinugawa Kitakanto Expressway JCT. -

El Sable Viene Bajito

Image not found or type unknown www.juventudrebelde.cu Image not found or type unknown De Ichiro Suzuki se echará de menos su experiencia competitiva. Autor: Internet Publicado: 21/09/2017 | 05:28 pm El sable viene bajito Pese a las anunciadas ausencias de sus estrellas «internacionales», el elenco nipón muestra una sólida escuadra de probada calidad Publicado: Domingo 09 diciembre 2012 | 02:18:14 am. Publicado por: Raiko Martín Al equipo de Japón le teme todo el mundo y ese miedo no es gratuito. Viene precedido por los inobjetables títulos conquistados en las únicas dos ediciones del Clásico Mundial de béisbol, y en la capacidad probada de armar un sólida escuadra, aunque no estén disponibles aquellos actualmente enrolados en las Grandes Ligas estadounidenses. Para algunos, las anunciadas ausencias de sus estrellas «internacionales» restan potencia al elenco nipón. Sin embargo, no son pocos los analistas que las asumen como una ventaja, teniendo en cuenta que estas figuras tienden a no seguir el ritmo de trabajo de sus compañeros. La mayoría de los expertos se inclinan a pensar que será el diestro Yu Darvish el que más se extrañe dentro de la nómina, aun cuando tampoco hayan aceptado la invitación notables lanzadores como Hiroki Kuroda y Hisashi Iwakuma. Si hay un área en la que sobre talento dentro, esa es la de los lanzadores. De el icónico Ichiro Suzuki se echará de menos la experiencia y su halo mediático, pero los entendidos señalan al menos cinco jardineros con la capacidad de batear, correr o defender con tanta o mayor calidad que él. -

“We'll Embrace One Another and Go On, All Right?” Everyday Life in Ozu

“We’ll embrace one another and go on, all right?” Everyday life in Ozu Yasujirô’s post-war films 1947-1949. University of Turku Faculty of Humanities Cultural History Master’s thesis Topi E. Timonen 17.5.2019 The originality of this thesis has been checked in accordance with the University of Turku quality assurance system using the Turnitin OriginalityCheck service. UNIVERSITY OF TURKU School of History, Culture and Arts Studies Faculty of Humanities TIMONEN, TOPI E.: “We’ll embrace one another and go on, all right?” Everyday life in Ozu Yasujirô’s post-war films 1947-1949. Master’s thesis, 84 pages. Appendix, 2 pages. Cultural history May 2019 Summary The subject of my master’s thesis is the depiction of everyday life in the post-war films of Japanese filmmaker Ozu Yasujirô (1903-1963). My primary sources are his three first post- war films: Record of a Tenement Gentleman (Nagaya shinshiroku, 1947), A Hen in the Wind (Kaze no naka no mendori, 1948) and Late Spring (Banshun, 1949). Ozu’s aim in his filmmaking was to depict the Japanese people, their society and their lives in a realistic fashion. My thesis offers a close reading of these films that focuses on the themes that are central in their everyday depiction. These themes include gender roles, poverty, children, nostalgia for the pre-war years, marital equality and the concept of arranged marriage, parenthood, and cultural juxtaposition between Japanese and American influences. The films were made under American censorship and I reflect upon this context while examining the presentation of the themes. -

List of Institutional Investors Signing up to “Principles for Responsible Institutional Investors” ≪Japan's Stewardship

List of institutional investors signing up to “Principles for Responsible Institutional Investors” ≪Japan’s Stewardship Code≫ - To promote sustainable growth of companies through investment and dialogue - As of June 30, 2021 【Total︓309】 Website (URL) where the announcement of the Website (URL) where the disclosure items described in Updates Updates Disclosure of Voting Stewardship Activity Institution’s name (alphabetical order) acceptance of the Code has been disclosed the Code have been disclosed for 2017 Revision for 2020 Revision Results Reasons for Votes Reports Website (URL) Trust banks(subtotal︓6) Mitsubishi UFJ Trust and Banking 1 https://www.tr.mufg.jp/ippan/release/pdf_mutb/200515_1.pdf https://www.tr.mufg.jp/houjin/jutaku/pdf/stewardship_ja_pdf.pdf ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ https://www.tr.mufg.jp/houjin/jutaku/pdf/stewardship_mutb_pdf.pdf?180905 Corporation 2 Mizuho Trust & Banking Co,. Ltd. https://www.mizuho-tb.co.jp/corporate/unyou/pdf/stewardship.pdf https://www.mizuho-tb.co.jp/corporate/unyou/pdf/stewardship.pdf ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ https://www.mizuho-tb.co.jp/corporate/unyou/stewardship_katsudo.html 3 Resona Bank, Limited. http://www.resonabank.co.jp/nenkin/sisan/prii/index.html https://www.resonabank.co.jp/nenkin/sisan/prii/pdf/Stewardship_code_policy.pdf ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ https://www.resona-am.co.jp/investors/ssc.html 4 Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Bank, Limited https://www.smtb.jp/business/instrument/voting/stewardship.html https://www.smtb.jp/business/instrument/voting/stewardship.html ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ https://www.smtb.jp/business/instrument/voting/stewardship_activity.html 5 The Nomura Trust and Banking Co., Ltd. http://www.nomura-trust.co.jp/news/140528.html https://www.nomura-trust.co.jp/company/stewardship/ ○ ○ △ ○ https://www.nomura-trust.co.jp/company/stewardship/pdf/hyouka2020.pdf The Norinchukin Trust and Banking 6 http://www.nochutb.co.jp/about/governance.html http://www.nochutb.co.jp/about/governance.html ○ ○ △ ○ http://www.nochutb.co.jp/about/pdf/2020_stewardship.pdf Co.,Ltd. -

Jprail-Timetable-Kamiki.Pdf

JPRail.com train timetable ThisJPRail.com timetable contains the following trains: JPRail.com 1. JR limited express trains in Hokkaido, Hokuriku, Chubu and Kansai area 2. Major local train lines in Hokkaido 3. Haneda airport access trains for the late arrival and the early departure 4. Kansai airport access trains for the late arrival and the early departure You may find the train timetables in the links below too. 1. JR East official timetable (Hokkaido, Tohoku, Akita, Yamagata, Joetsu and Hokuriku Shinkansens, Narita Express, Limited Express Azusa, Odoriko, Hitachi, Nikko, Inaho, and major joyful trains in eastern Japan) 2.JPRail.comJR Kyushu official timetable (Kyushu Shinkansen, JPRail.com Limited Express Yufuin no Mori, Sonic, Kamome, and major D&S trains) Timetable index (valid until mid March 2020) *The timetables may be changed without notice. The Limited Express Super Hokuto (Hakodate to Sapporo) 4 The Limited Express Super Hokuto (Sapporo to Hakodate) 5 JPRail.comThe Limited Express Suzuran (Muroran to Sapporo) JPRail.com6 The Limited Express Suzuran (Sapporo to Muroran) 6 The Limited Express Kamui and Lilac (Sapporo to Asahikawa) 7 The Limited Express Kamui and Lilac (Asahikawa to Sapporo) 8 The Limited Express Okhotsk and Taisetsu 9 The Limited Express Super Ozora and Super Tokachi (Sapporo to Obihiro and Kushiro) 10 The Limited Express Super Ozora and Super Tokachi (Obihiro and Kushiro to Sapporo) 11 JPRail.comThe Limited Express Soya and Sarobetsu JPRail.com12 Hakodate line local train between Otaru and Oshamambe (Oshamambe -

¡Cuidado Con El Balón

14 DEPORTES DOMINGO 09 DE DICIEMBRE DE 2012 juventud rebelde por JOSÉ LUIS LÓPEZ SADO [email protected] fotos TOMADAS DE INTERNET ¡Cuidado con NO hace falta hacer un sondeo nacional para sentenciar que nuestros jóvenes conocen las particularidades, como deportistas y seres humanos, de sus ídolos futbolísticos, entre los que aparecen Lionel Messi, Cristiano Ronaldo, el balón: es de oro! Andrés Iniesta o Zlatan Ibrahimovic, por solo citar cuatro ejemplos. El próximo 7 de enero, la FIFA dará a conocer quién ganó el Balón Muestra de ello es que a nuestra redacción han llegado correos electrónicos y llamadas telefónicas de jóvenes que de Oro 2012. Hoy, JR comparte con ustedes la historia y actualidad solicitan información sobre la historia del archifamoso Balón de este galardón de Oro, especialmente la rica disputa acerca de quién se lo agenciará este año. ÉRASE UN BALÓN… Según ha trascendido, el Balón de Oro fue un premio indi- vidual otorgado, desde el año 1956 hasta el 2009, por la revista francesa especializada France Football al mejor juga- dor inscrito cada año en algún campeonato de fútbol profe- sional europeo. Por ese motivo también se le conoció como el Premio al mejor jugador europeo del año (European Foot- baller of the Year award). Instituido en 1956 por Gabriel Hanot, director de la men- cionada revista y precursor de la Copa de Campeones de Europa, en un principio el galardón estuvo dirigido exclusiva- mente a futbolistas de nacionalidad europea. El primer gana- dor fue el inglés Stanley Matthews, quien ese año jugaba para el Blackpool Football Club. -

Copyrighted Material

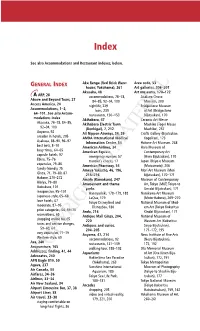

18_543229 bindex.qxd 5/18/04 10:06 AM Page 295 Index See also Accommodations and Restaurant indexes, below. GENERAL INDEX Aka Renga (Red Brick Ware- Area code, 53 house; Yokohama), 261 Art galleries, 206–207 Akasaka, 48 Art museums, 170–172 A ARP, 28 accommodations, 76–78, Asakura Choso Above and Beyond Tours, 27 84–85, 92–94, 100 Museum, 200 Access America, 24 nightlife, 229 Bridgestone Museum Accommodations, 1–2, bars, 239 of Art (Bridgestone 64–101. See also Accom- restaurants, 150–153 Bijutsukan), 170 modations Index Akihabara, 47 Ceramic Art Messe Akasaka, 76–78, 84–85, Akihabara Electric Town Mashiko (Togei Messe 92–94, 100 (Denkigai), 7, 212 Mashiko), 257 Aoyama, 92 All Nippon Airways, 34, 39 Crafts Gallery (Bijutsukan arcades in hotels, 205 AMDA International Medical Kogeikan), 173 Asakusa, 88–90, 96–97 Information Center, 54 Hakone Art Museum, 268 best bets, 8–10 American Airlines, 34 Hara Museum of busy times, 64–65 American Express Contemporary Art capsule hotels, 97 emergency number, 57 (Hara Bijutsukan), 170 Ebisu, 75–76 traveler’s checks, 17 Japan Ukiyo-e Museum expensive, 79–86 American Pharmacy, 54 (Matsumoto), 206 family-friendly, 75 Ameya Yokocho, 46, 196, Mori Art Museum (Mori Ginza, 71, 79–80, 87 215–216 Bijutsukan), 170–171 Hakone, 270–272 Amida (Kamakura), 247 Museum of Contemporary Hibiya, 79–80 Amusement and theme Art, Tokyo (MOT; Tokyo-to Ikebukuro, 101 parks Gendai Bijutsukan), 171 inexpensive, 95–101 Hanayashiki, 178–179, 188 Narukawa Art Museum Japanese-style, 65–68 LaQua, 179 (Moto-Hakone), 269–270 love hotels, -

FR-1985-11-21.Pdf

11-21-85 Thursday Vol. 50 No. 225- November 21, 1985 Pages 48073-48160 Briefings on How To Use the Federal Register— For information on briefings in Philadelphia, PA, see announcement on the inside cover of this issue. Selected Subjects Aviation Safety Federal Aviation Administration Bridges Coast Guard Credit Union National Credit Union Administration Energy National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Marine Safety Coast Guard Medicaid Health Care Financing Administration Medical Devices Food and Drug Administration Postal Service Postal Service Radio Broadcasting Federal Communications Commission Television Broadcasting Federal Communications Commission Warehouses Commodity Credit Corporation Wine Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms Bureau II Federal Register / Voi. 50, No. 225 / Thursday, November 21,1985 FEDERAL REGISTER Published daily, Monday through Friday, (not published on Saturdays, Sundays, or on official holidays), by the Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC 20408, under the Federal Register Act (49 Stat. 500, as amended; 44 U.S.C. Ch. 15) and the regulations of the Administrative Committee of the Federal Register (1 CFR Ch. I). Distribution is made only by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402. The Federal Register provides a uniform system for making available to the public regulations and legal notices issued by Federal agencies. These include Presidential proclamations and Executive Orders and Federal agency documents having general applicability and legal effect, documents required to be published by act of Congress and other Federal agency documents of public interest. Documents are on file for public inspection in the Office of the Federal Register the day before they are published, unless earlier filing is requested by the issuing agency. -

UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Ainu Fever: Indigenous Representation in a Transnational Visual Economy, 1868–1933 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/83f1b2rm Author Spiker, Christina Marie Publication Date 2015 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, IRVINE Ainu Fever: Indigenous Representation in a Transnational Visual Economy, 1868–1933 DISSERTATION submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in Visual Studies by Christina M. Spiker Dissertation Committee: Professor Bert Winther-Tamaki, Chair Associate Professor Fatimah Tobing Rony Associate Professor Roberta Wue 2015 © 2015 Christina M. Spiker TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF FIGURES iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS vi CURRICULUM VITAE vii ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION x INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER 1: ‘Civilized’ Men and ‘Superstitious’ Women: Isabella Bird, Edward 42 Greey, and Late Nineteenth-Century Visualizations of the Ainu CHAPTER 2: Narrating a Multi-Layered Visual Experience at the 1904 St. 103 Louis Exposition: W. J. McGee, Frederick Starr, and Pete Gorō CHAPTER 3: Art, Science, and the Artist-Explorer: Arnold Genthe and A. H. 144 Savage Landor, 1893–1908 CHAPTER 4: A Modern Tourist Experience in Shiraoi: Kondō Kōichiro’s 187 Illustrations in the Yomiuri Shinbun, 1917 CHAPTER 5: Asserting Identity in the Face of Disappearance: Katahira 223 Tomijirō, Takekuma Tokusaburō, and Reverend John Batchelor, 1918–1933 EPILOGUE: Ainu Visual Economy Enters the Digital Age: New Battlegrounds 271 of Representation BIBLIOGRAPHY 287 ii LIST OF FIGURES Figure Page 1 “Hairy Ainu to be Brought to America,” New York Tribune, 1904 2 2 Broughton, “A Man & Woman of Volcano Bay,” 1804 12 3 Bird, “Ainos of Yezo” frontispiece, 1880 64 4 Stillfried, “Ainos,” ca. -

JAPAN RAIL PASS Validity

※Terms of use for Kansai Area Passes should conform to below. JAPAN RAIL PASS validity 1. Transportation services ■ The JAPAN RAIL PASS is valid for the railways, buses, and ferry boats shown in Table 1. Railways: All JR Group Railways-Shinkansen"bullet trains" (except any reserved or non-reserved seat on “NOZOMI”and”MIZUHO”trains) limited express trains, express trains, and rapid or local trains. (With some exceptions) *JAPAN RAIL PASS holders can also use the Tokyo monorail. *Aoimori Railway (Metoki-Aomori. However, the use of local or rapid trains between Aomori-Hachinohe, Aomori-Noheji and Hachinohe-Noheji is permitted. Passengers disembarking on Aoimori Railway lines in these sections must pay separate fares. However, passengers disembarking at Aomori Station, Noheji Station, or Hachinohe Station do not need to pay separate fares. Buses: Local lines of JR bus companies*1 (excluding some local lines) (Pass validity for particular routes is subject to change.) *1 JR Hokkaido Bus, JR Bus Tohoku, JR Bus Kanto, JR Tokai Bus, West Japan JR Bus, Chugoku JR Bus, JR Kyushu Bus *The PASS is not valid for travel on express bus routes operated by JR bus companies. Ferry: Only the JR Miyajima ferry is covered. The JR Hakata-Pusan (Korea) ferry is not covered. Important notes: The JAPAN RAIL PASS is not valid for any seats, reserved or non-reserved, on “NOZOMI” and “MIZUHO” trains on the Tokaido, Sanyo and Kyushu Shinkansen lines. (The pass holders must take “HIKARI,” “SAKURA,” “KODAMA,” or “TSUBAME” trains.) If you use a “NOZOMI” or “MIZUHO” train, you must pay the basic fare and the limited express charge, and for a Green Car the Green Car surcharge. -

Hakuba Kogen Hotel, Hakuba Marchen House, Hakuba

HAKUBA KOGEN HOTEL, HAKUBA MARCHEN HOUSE, HITACHI TELECOM TECHNOLOGIES, LTD., HITACHI HOTEL SAN MARUTE, HOTEL SANKEIEN, HOTEL HAKUBA MOMINOKI HOTEL, HAKUBA MONTBIEN, TRANSPORT SYSTEM LTD., HITOKUWADA TENNOUSAI SANNOUKAKU, HOTEL SEIHUU-EN, HOTEL SEIZAN, HAKUBA PARK HOTEL, HAKUBA PIEMON YAMAJU, HOZONKAI, HIYOSHI VILLAGE, HOKKAIDO SHIEI KEIBA HOTEL SHIGA ASPEN, HOTEL SHIGA SUNVALLEY, HOTEL HAKUBA RESORT HOTEL LA NEIGE, HAKUBA RESORT KUMIAI, HOKUREN NOGYO KYODO KUMIAI RENGOKAI, SHINANOEN, HOTEL SHINANOJI, HOTEL SHINONOI, HOTEL LA NEIGE HIGASHIKAN, HAKUBA ROYAL HOTEL, HOKURIKU REGIONAL CONSTRUCTION BREAU, HOTEL SHINSHO, HOTEL SHIRAKABA(SANADA TOWN), HAKUBA SANROKU MINSHUKU KITAYA-KAN, HAKUBA HOKUSHIN CHIHO JIMUSHO, HOKUSHIN ESTATE, HOTEL SHIRAKABA-SOU(SHIGA-KOGEN AREA), HOTEL SKI KAN, HAKUBA SOIRU KOGYO, HAKUBA TOKYU HOKUSHIN GENERAL HOSPITAL, HOKUSHIN KENSETSU SHIROGANE, HOTEL SHOWAEN, HOTEL SILK WOOD, HOTEL, HAKUBA VILLAGE, HAKUBA VILLAGE SKI CLUB, JIGYO KYODO KUMIAI, HOKUSHIN SPORT MEDICAL HOTEL SILK-INN MADARAO, HOTEL SOYOKAZE, HOTEL HAKUBAKAN CO., LTD., HAKUBAMURA ASSOCIATION, HOKUTO SANGYO CO., LTD., HOLIDAY ST.MORITZ SHIGA, HOTEL SUEHIRO-KAN, HOTEL KENSETSUGYOKUMIAI, HAKUBAMURA INN EXPRESS NAGANO, HOMERUN, HOMUSHO, SUIMEIKAN, HOTEL SUNLIGHT MYOUKOU, HOTEL OLYMPIQUEÅEPARALYMPIQUE SUISHINIINKAI, HOMUSHO NAGOYA NYUKOKU KANRI KYOKU NAGOYA SUNROUTE MATSUMOTO, HOTEL SUNROUTE HAKURA-SOU, HAKU-UN-ROU, HAMADA KUKO SHUTTYOJO, HOMUSHO OSAKA NYUKOKU SHIGAKOGEN, HOTEL TAGAWA, HOTEL TAIGAKUKAN, TERUHIKO,SUPERINTENDENT OF MPC VENUE, HAMANO KANRIKYOKU