UC Irvine UC Irvine Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feelin' Casual! Feelin' Casual!

Feelin’ casual! Feelin’ casual! to SENDAI to YAMAGATA NIIGATA Very close to Aizukougen Mt. Chausu NIIGATA TOKYO . Very convenient I.C. Tohoku Expressway Only 50minutes by to NIKKO and Nasu Nasu FUKUSHIMA other locations... I.C. SHINKANSEN. JR Tohoku Line(Utsunomiya Line) Banetsu Utsunomiya is Kuroiso Expressway FUKUSHIMA AIR PORT Yunishigawa KORIYAMA your gateway to Tochigi JCT. Yagan tetsudo Line Shiobara Nasu Nishinasuno- shiobara shiobara I.C. Nishi- nasuno Tohoku Shinkansen- Kawaji Kurobane TOBU Utsunomiya Line Okukinu Kawamata 3 UTSUNO- UTSUNOMIYA MIYA I.C. Whole line opening Mt. Nantai Kinugawa Jyoutsu Shinkansen Line to traffic schedule in March,2011 Nikko KANUMA Tobu Bato I.C. Utsunomiya UTSUNOMIYA 2 to NAGANO TOCHIGI Line TOCHIGI Imaichi TSUGA Tohoku Shinkansen Line TAKA- JCT. MIBU USTUNOMIYA 6 SAKI KAMINOKAWA 1 Nagono JCT. IWAFUNE I.C. 1 Utsunomiya → Nikko JCT. Kitakanto I.C. Karasu Shinkansen Expressway yama Line HITACHI Ashio NAKAMINATO JR Nikko Line Utsunomiya Tohoku Shinkansen- I.C. I.C. TAKASAKI SHIN- Utsunomiya Line TOCHIGI Kanuma Utsunomiya Tobu Nikko Line IBARAKI AIR PORT Tobu Motegi KAWAGUCHI Nikko, where both Japanese and international travelers visit, is Utsuno- 5 JCT. miya MISATO OMIYA an international sightseeing spot with many exciting spots to TOCHIGI I.C. see. From Utsunomiya, you can enjoy passing through Cherry Tokyo blossom tunnels or a row of cedar trees on Nikko Highway. Utsunomiya Mashiko Tochigi Kaminokawa NERIMA Metropolitan Mibu I.C. Moka I.C. Expressway Tsuga I.C. SAPPORO JCT. Moka Kitakanto Expressway UENO Nishikiryu I.C. ASAKUSA JR Ryomo Line Tochigi TOKYO Iwafune I.C. Kasama 2 Utsunomiya → Kinugawa Kitakanto Expressway JCT. -

List of Institutional Investors Signing up to “Principles for Responsible Institutional Investors” ≪Japan's Stewardship

List of institutional investors signing up to “Principles for Responsible Institutional Investors” ≪Japan’s Stewardship Code≫ - To promote sustainable growth of companies through investment and dialogue - As of June 30, 2021 【Total︓309】 Website (URL) where the announcement of the Website (URL) where the disclosure items described in Updates Updates Disclosure of Voting Stewardship Activity Institution’s name (alphabetical order) acceptance of the Code has been disclosed the Code have been disclosed for 2017 Revision for 2020 Revision Results Reasons for Votes Reports Website (URL) Trust banks(subtotal︓6) Mitsubishi UFJ Trust and Banking 1 https://www.tr.mufg.jp/ippan/release/pdf_mutb/200515_1.pdf https://www.tr.mufg.jp/houjin/jutaku/pdf/stewardship_ja_pdf.pdf ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ https://www.tr.mufg.jp/houjin/jutaku/pdf/stewardship_mutb_pdf.pdf?180905 Corporation 2 Mizuho Trust & Banking Co,. Ltd. https://www.mizuho-tb.co.jp/corporate/unyou/pdf/stewardship.pdf https://www.mizuho-tb.co.jp/corporate/unyou/pdf/stewardship.pdf ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ https://www.mizuho-tb.co.jp/corporate/unyou/stewardship_katsudo.html 3 Resona Bank, Limited. http://www.resonabank.co.jp/nenkin/sisan/prii/index.html https://www.resonabank.co.jp/nenkin/sisan/prii/pdf/Stewardship_code_policy.pdf ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ https://www.resona-am.co.jp/investors/ssc.html 4 Sumitomo Mitsui Trust Bank, Limited https://www.smtb.jp/business/instrument/voting/stewardship.html https://www.smtb.jp/business/instrument/voting/stewardship.html ○ ○ ○ ○ ○ https://www.smtb.jp/business/instrument/voting/stewardship_activity.html 5 The Nomura Trust and Banking Co., Ltd. http://www.nomura-trust.co.jp/news/140528.html https://www.nomura-trust.co.jp/company/stewardship/ ○ ○ △ ○ https://www.nomura-trust.co.jp/company/stewardship/pdf/hyouka2020.pdf The Norinchukin Trust and Banking 6 http://www.nochutb.co.jp/about/governance.html http://www.nochutb.co.jp/about/governance.html ○ ○ △ ○ http://www.nochutb.co.jp/about/pdf/2020_stewardship.pdf Co.,Ltd. -

Jprail-Timetable-Kamiki.Pdf

JPRail.com train timetable ThisJPRail.com timetable contains the following trains: JPRail.com 1. JR limited express trains in Hokkaido, Hokuriku, Chubu and Kansai area 2. Major local train lines in Hokkaido 3. Haneda airport access trains for the late arrival and the early departure 4. Kansai airport access trains for the late arrival and the early departure You may find the train timetables in the links below too. 1. JR East official timetable (Hokkaido, Tohoku, Akita, Yamagata, Joetsu and Hokuriku Shinkansens, Narita Express, Limited Express Azusa, Odoriko, Hitachi, Nikko, Inaho, and major joyful trains in eastern Japan) 2.JPRail.comJR Kyushu official timetable (Kyushu Shinkansen, JPRail.com Limited Express Yufuin no Mori, Sonic, Kamome, and major D&S trains) Timetable index (valid until mid March 2020) *The timetables may be changed without notice. The Limited Express Super Hokuto (Hakodate to Sapporo) 4 The Limited Express Super Hokuto (Sapporo to Hakodate) 5 JPRail.comThe Limited Express Suzuran (Muroran to Sapporo) JPRail.com6 The Limited Express Suzuran (Sapporo to Muroran) 6 The Limited Express Kamui and Lilac (Sapporo to Asahikawa) 7 The Limited Express Kamui and Lilac (Asahikawa to Sapporo) 8 The Limited Express Okhotsk and Taisetsu 9 The Limited Express Super Ozora and Super Tokachi (Sapporo to Obihiro and Kushiro) 10 The Limited Express Super Ozora and Super Tokachi (Obihiro and Kushiro to Sapporo) 11 JPRail.comThe Limited Express Soya and Sarobetsu JPRail.com12 Hakodate line local train between Otaru and Oshamambe (Oshamambe -

Copyrighted Material

18_543229 bindex.qxd 5/18/04 10:06 AM Page 295 Index See also Accommodations and Restaurant indexes, below. GENERAL INDEX Aka Renga (Red Brick Ware- Area code, 53 house; Yokohama), 261 Art galleries, 206–207 Akasaka, 48 Art museums, 170–172 A ARP, 28 accommodations, 76–78, Asakura Choso Above and Beyond Tours, 27 84–85, 92–94, 100 Museum, 200 Access America, 24 nightlife, 229 Bridgestone Museum Accommodations, 1–2, bars, 239 of Art (Bridgestone 64–101. See also Accom- restaurants, 150–153 Bijutsukan), 170 modations Index Akihabara, 47 Ceramic Art Messe Akasaka, 76–78, 84–85, Akihabara Electric Town Mashiko (Togei Messe 92–94, 100 (Denkigai), 7, 212 Mashiko), 257 Aoyama, 92 All Nippon Airways, 34, 39 Crafts Gallery (Bijutsukan arcades in hotels, 205 AMDA International Medical Kogeikan), 173 Asakusa, 88–90, 96–97 Information Center, 54 Hakone Art Museum, 268 best bets, 8–10 American Airlines, 34 Hara Museum of busy times, 64–65 American Express Contemporary Art capsule hotels, 97 emergency number, 57 (Hara Bijutsukan), 170 Ebisu, 75–76 traveler’s checks, 17 Japan Ukiyo-e Museum expensive, 79–86 American Pharmacy, 54 (Matsumoto), 206 family-friendly, 75 Ameya Yokocho, 46, 196, Mori Art Museum (Mori Ginza, 71, 79–80, 87 215–216 Bijutsukan), 170–171 Hakone, 270–272 Amida (Kamakura), 247 Museum of Contemporary Hibiya, 79–80 Amusement and theme Art, Tokyo (MOT; Tokyo-to Ikebukuro, 101 parks Gendai Bijutsukan), 171 inexpensive, 95–101 Hanayashiki, 178–179, 188 Narukawa Art Museum Japanese-style, 65–68 LaQua, 179 (Moto-Hakone), 269–270 love hotels, -

FR-1985-11-21.Pdf

11-21-85 Thursday Vol. 50 No. 225- November 21, 1985 Pages 48073-48160 Briefings on How To Use the Federal Register— For information on briefings in Philadelphia, PA, see announcement on the inside cover of this issue. Selected Subjects Aviation Safety Federal Aviation Administration Bridges Coast Guard Credit Union National Credit Union Administration Energy National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration Marine Safety Coast Guard Medicaid Health Care Financing Administration Medical Devices Food and Drug Administration Postal Service Postal Service Radio Broadcasting Federal Communications Commission Television Broadcasting Federal Communications Commission Warehouses Commodity Credit Corporation Wine Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms Bureau II Federal Register / Voi. 50, No. 225 / Thursday, November 21,1985 FEDERAL REGISTER Published daily, Monday through Friday, (not published on Saturdays, Sundays, or on official holidays), by the Office of the Federal Register, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC 20408, under the Federal Register Act (49 Stat. 500, as amended; 44 U.S.C. Ch. 15) and the regulations of the Administrative Committee of the Federal Register (1 CFR Ch. I). Distribution is made only by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC 20402. The Federal Register provides a uniform system for making available to the public regulations and legal notices issued by Federal agencies. These include Presidential proclamations and Executive Orders and Federal agency documents having general applicability and legal effect, documents required to be published by act of Congress and other Federal agency documents of public interest. Documents are on file for public inspection in the Office of the Federal Register the day before they are published, unless earlier filing is requested by the issuing agency. -

JAPAN RAIL PASS Validity

※Terms of use for Kansai Area Passes should conform to below. JAPAN RAIL PASS validity 1. Transportation services ■ The JAPAN RAIL PASS is valid for the railways, buses, and ferry boats shown in Table 1. Railways: All JR Group Railways-Shinkansen"bullet trains" (except any reserved or non-reserved seat on “NOZOMI”and”MIZUHO”trains) limited express trains, express trains, and rapid or local trains. (With some exceptions) *JAPAN RAIL PASS holders can also use the Tokyo monorail. *Aoimori Railway (Metoki-Aomori. However, the use of local or rapid trains between Aomori-Hachinohe, Aomori-Noheji and Hachinohe-Noheji is permitted. Passengers disembarking on Aoimori Railway lines in these sections must pay separate fares. However, passengers disembarking at Aomori Station, Noheji Station, or Hachinohe Station do not need to pay separate fares. Buses: Local lines of JR bus companies*1 (excluding some local lines) (Pass validity for particular routes is subject to change.) *1 JR Hokkaido Bus, JR Bus Tohoku, JR Bus Kanto, JR Tokai Bus, West Japan JR Bus, Chugoku JR Bus, JR Kyushu Bus *The PASS is not valid for travel on express bus routes operated by JR bus companies. Ferry: Only the JR Miyajima ferry is covered. The JR Hakata-Pusan (Korea) ferry is not covered. Important notes: The JAPAN RAIL PASS is not valid for any seats, reserved or non-reserved, on “NOZOMI” and “MIZUHO” trains on the Tokaido, Sanyo and Kyushu Shinkansen lines. (The pass holders must take “HIKARI,” “SAKURA,” “KODAMA,” or “TSUBAME” trains.) If you use a “NOZOMI” or “MIZUHO” train, you must pay the basic fare and the limited express charge, and for a Green Car the Green Car surcharge. -

Hakuba Kogen Hotel, Hakuba Marchen House, Hakuba

HAKUBA KOGEN HOTEL, HAKUBA MARCHEN HOUSE, HITACHI TELECOM TECHNOLOGIES, LTD., HITACHI HOTEL SAN MARUTE, HOTEL SANKEIEN, HOTEL HAKUBA MOMINOKI HOTEL, HAKUBA MONTBIEN, TRANSPORT SYSTEM LTD., HITOKUWADA TENNOUSAI SANNOUKAKU, HOTEL SEIHUU-EN, HOTEL SEIZAN, HAKUBA PARK HOTEL, HAKUBA PIEMON YAMAJU, HOZONKAI, HIYOSHI VILLAGE, HOKKAIDO SHIEI KEIBA HOTEL SHIGA ASPEN, HOTEL SHIGA SUNVALLEY, HOTEL HAKUBA RESORT HOTEL LA NEIGE, HAKUBA RESORT KUMIAI, HOKUREN NOGYO KYODO KUMIAI RENGOKAI, SHINANOEN, HOTEL SHINANOJI, HOTEL SHINONOI, HOTEL LA NEIGE HIGASHIKAN, HAKUBA ROYAL HOTEL, HOKURIKU REGIONAL CONSTRUCTION BREAU, HOTEL SHINSHO, HOTEL SHIRAKABA(SANADA TOWN), HAKUBA SANROKU MINSHUKU KITAYA-KAN, HAKUBA HOKUSHIN CHIHO JIMUSHO, HOKUSHIN ESTATE, HOTEL SHIRAKABA-SOU(SHIGA-KOGEN AREA), HOTEL SKI KAN, HAKUBA SOIRU KOGYO, HAKUBA TOKYU HOKUSHIN GENERAL HOSPITAL, HOKUSHIN KENSETSU SHIROGANE, HOTEL SHOWAEN, HOTEL SILK WOOD, HOTEL, HAKUBA VILLAGE, HAKUBA VILLAGE SKI CLUB, JIGYO KYODO KUMIAI, HOKUSHIN SPORT MEDICAL HOTEL SILK-INN MADARAO, HOTEL SOYOKAZE, HOTEL HAKUBAKAN CO., LTD., HAKUBAMURA ASSOCIATION, HOKUTO SANGYO CO., LTD., HOLIDAY ST.MORITZ SHIGA, HOTEL SUEHIRO-KAN, HOTEL KENSETSUGYOKUMIAI, HAKUBAMURA INN EXPRESS NAGANO, HOMERUN, HOMUSHO, SUIMEIKAN, HOTEL SUNLIGHT MYOUKOU, HOTEL OLYMPIQUEÅEPARALYMPIQUE SUISHINIINKAI, HOMUSHO NAGOYA NYUKOKU KANRI KYOKU NAGOYA SUNROUTE MATSUMOTO, HOTEL SUNROUTE HAKURA-SOU, HAKU-UN-ROU, HAMADA KUKO SHUTTYOJO, HOMUSHO OSAKA NYUKOKU SHIGAKOGEN, HOTEL TAGAWA, HOTEL TAIGAKUKAN, TERUHIKO,SUPERINTENDENT OF MPC VENUE, HAMANO KANRIKYOKU -

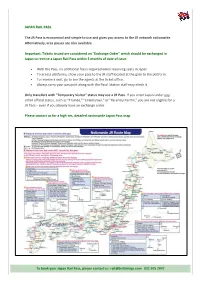

JAPAN RAIL PASS the JR Pass Is Economical And

JAPAN RAIL PASS The JR Pass is economical and simple to use and gives you access to the JR network nationwide. Alternatively, area passes are also available. Important: Tickets issued are considered an "Exchange Order" which should be exchanged in Japan to receive a Japan Rail Pass within 3 months of date of issue. With the Pass, no additional fee is required when reserving seats in Japan. To access platforms, show your pass to the JR staff located at the gate to the platform. To reserve a seat, go to see the agents at the ticket office. Always carry your passport along with the Pass! Station staff may check it. Only travellers with "Temporary Visitor" status may use a JR Pass. If you enter Japan under any other official status, such as "Trainee," "Entertainer," or "Re-entry Permit," you are not eligible for a JR Pass – even if you already have an exchange order. Please contact us for a high-res, detailed nationwide Japan Pass map. To book your Japan Rail Pass, please contact us [email protected] 021 975 2047 Activating your Japan Rail Pass In order to activate your JR Pass please exchange your voucher at a JR office. These offices can be found at the airport (Narita, New Chitose and Kansai) or in the main train stations. An Exchange Order and Pass are ONLY valid for the person named on the Exchange Order and Japan Rail Pass and are not transferable. You will need: Your passport with entry stamp AND your Japan Pass Exchange order ticket. 1. -

Kisaburo-, Kuniyoshi and the “Living Doll”

100 Kisaburo-, Kuniyoshi and the “Living Doll” Kinoshita Naoyuki or many years now, I have been researching different aspects of nineteenth-century Japanese culture, making a conscious decision Fnot to distinguish between “fine art” and “popular culture.” I clearly remember the occasion some twenty years ago that prompted me to adopt this approach. It was my first encounter with the termiki-ningyo - (“liv- ing dolls”), as coined in Japanese. I had absolutely no idea what the phrase meant, nor even how to pronounce the Chinese characters. The majority of modern Japanese, unfamiliar with the term, end up pronouncing it nama- ningyo-. The impulse to pronounce the first character asnama derives from its meaning of something “vivid” or “fresh” (namanamashii). In the culinary idiom, the adjective brings to mind not grilled or boiled fish, but raw fish (sashimi) at the instant the dish is set down, or even the moments before- hand, as one’s mouth begins to water watching the fish being prepared. Now I have a little better understanding of what “living dolls” means. In the city of Edo (now Tokyo), a popular form of street entertainment was the re-creation of themes from legends or history with life-size, lifelike < Fig. 2. Matsumoto Kisaburo-. Tani- dolls––an inanimate counterpart to the European tableau vivant of the gumi Kannon. 1871/1898. Wood, with same period. It is difficult to prove exactly whatiki meant to Japanese peo- pigment, textile, glass, horsehair. 160 cm. ple in the nineteenth century, but the term iki-ningyo- was a neologism that Jo-kokuji, Kumamoto City, Kumamoto first appeared in connection with a public spectacle, known as amisemono , Prefecture mounted in Osaka in 1854. -

{Replace with the Title of Your Dissertation}

Japanese Transit-Oriented Development: The Framed Market and the Production of Alternative Landscapes A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Justin Price Jacobson IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Judith A. Martin and Roger P. Miller May 2010 © Justin Price Jacobson Acknowledgements The completion of this dissertation would not have been possible without assistance. I would like to thank the National Science Foundation and the Japan Foundation for fellowships used for the research and writing stages of the project. The SSRC Japan Studies Dissertation Workshop was another valuable source of support and encouragement. I would like to thank the following mentors for their help in various stages: Judith Martin and Roger Miller, who served as advisors for my graduate education and as readers of this dissertation; Ann Forsyth, who sponsored me through various research assistantships and agreed to be a reader; and Rod Squires, who chaired the examination. I also thank Abdi Samatar, whose research development class was instrumental in preparing the research proposal for this dissertation. My graduate school colleagues have been a tremendous help in encouraging me and offering their guidance. Although there are many I could name, I would especially like to thank Max Handler, Jonathan Schroeder and Tim Mennel. In Tokyo, I have benefited form the guidance of my faculty advisor at the University of Tokyo, Junichiro Okata, as well as Hideki Koizumi and Rikutaro Manabe. I also appreciate the help of various librarians at the University of Tokyo, especially the Department of Urban Engineering Library, as well as the National Diet Library and Setagaya Ward Central Library. -

Design of the Stations and Trains of JR East Railway Company

Interpretive Article Design of the Stations and Trains of JR East Railway Company Susumu Hashizume* and Koji Yamamoto** *Transport Rolling Stock Department Assistant Manager **Equipment Department Assistant Manager JR East Railway Company A feeling of "comfort" is an emotion that results from an awareness of the environment, circumstances, experience, and psychological status. For this reason, in order to ensure comfort, various conditions need to be taken into consideration and the space and articles involved need to be concretely identified. This process is none other than the process of design. Stations and trains that constitute the management resources of JR East Railway Company are designed from a variety of perspectives. This paper will attempt to explain our company's design concept of stations and trains taking historical flow into consideration. room of Shimbashi and listening to the apparently busy sound of 1 Introduction wooden sandals makes me feel that I have embarked on a trip A person feels comfort as a result of awareness or supplementation of without moving, providing me with a free yet wistful feeling" (Kocha external and internal elements such as the environment, no Ato (After Tea) 1911). Visitors to the rejuvenated former circumstances, experience, and psychological status. In the case of a Shimbashi Depot will surely think back to the history of railways and railway, human response is a composite of environmental conditions stations that began from this small structure (Figure 2). In the in the stations and trains, memories of having used such facilities in sections that follow, the design of the stations of JR East Railway the past, the characteristics of the location of the station, and the Company will be explained looking back into history route to be taken. -

Hokkaido Railway Company (JR Hokkaido) Corporate Planning Headquarters, Management Planning Department

20 Years After JNR Privatization Vol. 2 Hokkaido Railway Company (JR Hokkaido) Corporate Planning Headquarters, Management Planning Department Introduction Main Initiatives in Last 20 Years JR Hokkaido celebrated the 20th anniversary of its Safety and technology transfer establishment on 1 April this year. However, things have JR Hokkaido, which is a major transport provider in been far from plain sailing over this time, which includes Hokkaido, has taken a range of initiatives based on the Japan’s Lost Decade, caused by the collapse of the bubble principle of putting the customer first at all times with a economy in 1991. Hokkaido has not been isolated from firm focus on maintaining safety. As a company providing these events and, in particular, the bankruptcy of transportation, we must put safety before everything else, Hokkaido Takushoku Bank, one of the prefecture’s main so customers can ride our trains with full peace of mind. financial institutions, almost devastated the local Notwithstanding this emphasis, a number of serious economy. JR Hokkaido has also faced many difficulties accidents have occurred on JR Hokkaido lines. In from changes in the operating environment. We look February 1994, high winds derailed and overturned a back with deep emotion to think that it has been 20 years limited express travelling on the Sekisho Line, injuring since JR Hokkaido was established. 25 passengers. In March 2007, a local train on the When Japanese National Railways (JNR) was privatized, Sekihoku Line carrying many high-school students it was thought that JR Hokkaido would have the toughest collided with a large trailer at a level crossing, injuring time of the seven JR companies established.