Kisaburo-, Kuniyoshi and the “Living Doll”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

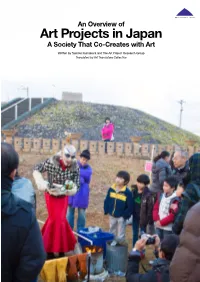

Art Projects in Japan a Society That Co-Creates with Art

An Overview of Art Projects in Japan A Society That Co-Creates with Art Written by Sumiko Kumakura and The Art Project Research Group Translated by Art Translators Collective Table of Contents Introduction 2 What are Art Projects?: History and Relationship to Local Areas 3 by Sumiko Kumakura and Yūichirō Nagatsu What are “Art Projects”? The Prehistory of Art Projects Regional Art Projects Column 1 An Overview of Large-Scale Art Festivals in Japan Case Studies from Japan’s Art Projects: Their History and Present State, 1990-2012 13 by The Art Project Research Group 1 Universities and Art Projects: Hands-On Learning and Hubs for Local Communities 2 Alternative Spaces and Art Projects: New Developments in Realizing Sustainable Support Systems 3 Museums and Art Projects: Community Projects Initiated by Museums 4 Urban Renewal and Art Projects: Building Social Capital 5 Art Project Staff: The Different Faces of Local Participants 6 Art Projects and Society: Social Inclusion and Art 7 Companies and Art Projects: Why Companies Support Art Projects 8 Artists and Art Projects: The Good and Bad of Large-Scale Art Festivals Held in Depopulated Regions 9 Trends After the 3.11 Earthquake: Art Projects Confronting Affected Areas of the Tōhoku Region Thinking about the Aesthetic and Social Value of Art Projects 28 by Sumiko Kumakura Departure from a Normative Definition of the Artwork Trends and Cultural Background of Art Project Research in Japan Local People as Evaluators of Art Projects Column 2 Case Studies of Co-Creative Projects 1: Jun Kitazawa’s -

Full Download

VOLUME 1: BORDERS 2018 Published by National Institute of Japanese Literature Tokyo EDITORIAL BOARD Chief Editor IMANISHI Yūichirō Professor Emeritus of the National Institute of Japanese 今西祐一郎 Literature; Representative Researcher Editors KOBAYASHI Kenji Professor at the National Institute of Japanese Literature 小林 健二 SAITō Maori Professor at the National Institute of Japanese Literature 齋藤真麻理 UNNO Keisuke Associate Professor at the National Institute of Japanese 海野 圭介 Literature KOIDA Tomoko Associate Professor at the National Institute of Japanese 恋田 知子 Literature Didier DAVIN Associate Professor at the National Institute of Japanese ディディエ・ダヴァン Literature Kristopher REEVES Associate Professor at the National Institute of Japanese クリストファー・リーブズ Literature ADVISORY BOARD Jean-Noël ROBERT Professor at Collège de France ジャン=ノエル・ロベール X. Jie YANG Professor at University of Calgary 楊 暁捷 SHIMAZAKI Satoko Associate Professor at University of Southern California 嶋崎 聡子 Michael WATSON Professor at Meiji Gakuin University マイケル・ワトソン ARAKI Hiroshi Professor at International Research Center for Japanese 荒木 浩 Studies Center for Collaborative Research on Pre-modern Texts, National Institute of Japanese Literature (NIJL) National Institutes for the Humanities 10-3 Midori-chō, Tachikawa City, Tokyo 190-0014, Japan Telephone: 81-50-5533-2900 Fax: 81-42-526-8883 e-mail: [email protected] Website: https//www.nijl.ac.jp Copyright 2018 by National Institute of Japanese Literature, all rights reserved. PRINTED IN JAPAN KOMIYAMA PRINTING CO., TOKYO CONTENTS -

The Otaku Phenomenon : Pop Culture, Fandom, and Religiosity in Contemporary Japan

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 12-2017 The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan. Kendra Nicole Sheehan University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Japanese Studies Commons, and the Other Religion Commons Recommended Citation Sheehan, Kendra Nicole, "The otaku phenomenon : pop culture, fandom, and religiosity in contemporary Japan." (2017). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 2850. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/2850 This Doctoral Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Humanities Department of Humanities University of Louisville Louisville, Kentucky December 2017 Copyright 2017 by Kendra Nicole Sheehan All rights reserved THE OTAKU PHENOMENON: POP CULTURE, FANDOM, AND RELIGIOSITY IN CONTEMPORARY JAPAN By Kendra Nicole Sheehan B.A., University of Louisville, 2010 M.A., University of Louisville, 2012 A Dissertation Approved on November 17, 2017 by the following Dissertation Committee: __________________________________ Dr. -

Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogunâ•Žs

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations School of Arts and Sciences October 2012 Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 1 Cecilia S. Seigle Ph.D. University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Economics Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Seigle, Cecilia S. Ph.D., "Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 1" (2012). Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations. 7. https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/7 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/7 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 1 Abstract In this study I shall discuss the marriage politics of Japan's early ruling families (mainly from the 6th to the 12th centuries) and the adaptation of these practices to new circumstances by the leaders of the following centuries. Marriage politics culminated with the founder of the Edo bakufu, the first shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu (1542-1616). To show how practices continued to change, I shall discuss the weddings given by the fifth shogun sunaT yoshi (1646-1709) and the eighth shogun Yoshimune (1684-1751). The marriages of Tsunayoshi's natural and adopted daughters reveal his motivations for the adoptions and for his choice of the daughters’ husbands. The marriages of Yoshimune's adopted daughters show how his atypical philosophy of rulership resulted in a break with the earlier Tokugawa marriage politics. -

©Copyright 2012 Sachi Schmidt-Hori

1 ©Copyright 2012 Sachi Schmidt-Hori 2 Hyperfemininities, Hypermasculinities, and Hypersexualities in Classical Japanese Literature Sachi Schmidt-Hori A Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2012 Reading Committee: Paul S. Atkins, Chair Davinder L. Bhowmik Tani E. Barlow Kyoko Tokuno Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Department of Asian Languages and Literature 3 University of Washington Abstract Hyperfemininities, Hypermasculinities, and Hypersexualities in Classical Japanese Literature Sachi Schmidt-Hori Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Associate Professor Paul S. Atkins Asian Languages and Literature This study is an attempt to elucidate the complex interrelationship between gender, sexuality, desire, and power by examining how premodern Japanese texts represent the gender-based ideals of women and men at the peak and margins of the social hierarchy. To do so, it will survey a wide range of premodern texts and contrast the literary depictions of two female groups (imperial priestesses and courtesans), two male groups (elite warriors and outlaws), and two groups of Buddhist priests (elite and “corrupt” monks). In my view, each of the pairs signifies hyperfemininities, hypermasculinities, and hypersexualities of elite and outcast classes, respectively. The ultimate goal of 4 this study is to contribute to the current body of research in classical Japanese literature by offering new readings of some of the well-known texts featuring the above-mentioned six groups. My interpretations of the previously studied texts will be based on an argument that, in a cultural/literary context wherein defiance merges with sexual attractiveness and/or sexual freedom, one’s outcast status transforms into a source of significant power. -

Animagazin 5. Sz. (2012. Szeptember 10.)

Felhasznált irodalom BBC cikkek/vallások: SINTÓ // pintergreg (Pintér Gergő) Shinto A sintó szorosan kapcsolódik Japánhoz és a japán kultúrához, mond- Encyclopedia of Shinto hatni egyidős velük, a japánok azonban nem vallásként tekintenek rá, inkább Wikipédia (en, hu) Shinto, életstílusnak nevezhetnénk. Shintai, Shinto shrine, Hokora stb. cikkei Green shinto, szentélyek Bevezető Kami a világban Terebess Ázsia A sintó egy kifejezetten helyi Bár a kami szót leggyakrabban Lexikon / Sintó vallás, és most nem csak arra gon- istennek fordítják, pontosabb lenne / Shimenawa dolok, hogy egy országra korlátozódik, a ,,lélek”, ,,szellem” kifejezés, azonban még Japánon belül is az, ugyanis a semmiképpen nem keverendő össze a / Esküvő követői nem egy egységes nagy val- nyugati istenfogalommal. A kami nem láshoz köthetők, hanem egy-egy helyi mindenható, nem tökéletes, időnként szentélyhez kötődő kamihoz. hibázik (akár az ember), természetétől A shintō (神道) szót két kanji fogva nem is különbözik tőle, ráadásul alkotja. Az első ,,shin” (神), jelentése ugyanabban a világban is él, mint az ,,lélek”, ,,isten”, és a kínai shên (isten) ember. De kami lehet egy erdő, egy szóból származik, a második a ,,to” hegy, vagy egy természeti jelenség pl. (道), ami a szintén kínai ,,tao” szóból vihar vagy cunami, de akár egy ember ered, és utat jelent. A sintó jelentése is kamivá válhat halála után. Ugyan- tehát ,,az istenek útja”. akkor nem minden kami rendelkezik A sintó felfogás szerint a lelkek névvel, ilyenkor úgy hivatkoznak rá, is ugyanabban a világban léteznek, mint pl. ennek vagy annak a helynek mint az emberek, bár létezik látható a kamija. (kenkai) és láthatatlan (yukai) világ, ezek nem különülnek el egymástól, hanem egy szoros egységet alkotnak és kapcsolatban állnak egymással. -

Rare Finds from Private Collections to Highlight Christie’S Old Master Paintings Sale in New York

For Immediate Release 14 January 2009 Contact: Erin McAndrew [email protected] 212.636.2680 RARE FINDS FROM PRIVATE COLLECTIONS TO HIGHLIGHT CHRISTIE’S OLD MASTER PAINTINGS SALE IN NEW YORK Important Old Master Paintings and Sculpture January 28, 2009 New York – Christie’s is pleased to announce details of its upcoming Important Old Master Paintings and Sculpture sale on January 28, 2009. The sale of over 200 items brings together a remarkable selection of artwork from the leading masters of European art, including a number of rare, privately- sourced, and historically significant items not seen on the market for decades. Highlights of the sale include an altarpiece study by Barocci, landscapes by Turner and Constable, Italian Renaissance tondi from the studio of Botticelli and the anonymous Master of Memphis, portraits by Girodet and Van Dyck, still lifes by Chardin and van Veerendael, and an excellent selection of bronze and wooden sculpture. Old Masters Week at Christie’s New York begins Monday, January 26, with a 6 p.m. lecture on J.M.W. Turner entitled, "Continuing Revolution: A Life in Watercolor" by Andrew Wilton, Former Curator of the Turner Collection, Tate Britain. On Tuesday, January 27 the sales begin with Part I of The Scholar’s Eye: Property from the Julius Held Collection. Important Old Master Paintings and Sculpture on January 28 is followed by Old Master and 19th Century Drawings on Thursday, January 29, and Part II of The Scholar’s Eye on Friday, January 30. Barocci’s Head of Saint John the Evangelist A thrilling recent discovery from a private collection, Head of Saint John the Evangelist is a full-scale study in oil on paper by the 16th century Italian painter Federico Barocci. -

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-48194-6 — Japan's Castles Oleg Benesch , Ran Zwigenberg Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-48194-6 — Japan's Castles Oleg Benesch , Ran Zwigenberg Index More Information Index 10th Division, 101, 117, 123, 174 Aichi Prefecture, 77, 83, 86, 90, 124, 149, 10th Infantry Brigade, 72 171, 179, 304, 327 10th Infantry Regiment, 101, 108, 323 Aizu, Battle of, 28 11th Infantry Regiment, 173 Aizu-Wakamatsu, 37, 38, 53, 74, 92, 108, 12th Division, 104 161, 163, 167, 268, 270, 276, 277, 12th Infantry Regiment, 71 278, 279, 281, 282, 296, 299, 300, 14th Infantry Regiment, 104, 108, 223 307, 313, 317, 327 15th Division, 125 Aizu-Wakamatsu Castle, 9, 28, 38, 62, 75, 17th Infantry Regiment, 109 77, 81, 277, 282, 286, 290, 311 18th Infantry Regiment, 124, 324 Akamatsu Miyokichi, 64 19th Infantry Regiment, 35 Akasaka Detached Palace, 33, 194, 1st Cavalry Division (US Army), 189, 190 195, 204 1st Infantry Regiment, 110 Akashi Castle, 52, 69, 78 22nd Infantry Regiment, 72, 123 Akechi Mitsuhide, 93 23rd Infantry Regiment, 124 Alnwick Castle, 52 29th Infantry Regiment, 161 Alsace, 58, 309 2nd Division, 35, 117, 324 Amakasu Masahiko, 110 2nd General Army, 2 Amakusa Shirō , 163 33rd Division, 199 Amanuma Shun’ichi, 151 39th Infantry Regiment, 101 American Civil War, 26, 105 3rd Cavalry Regiment, 125 anarchists, 110 3rd Division, 102, 108, 125 Ansei Purge, 56 3rd Infantry Battalion, 101 anti-military feeling, 121, 126, 133 47th Infantry Regiment, 104 Aoba Castle (Sendai), 35, 117, 124, 224 4th Division, 77, 108, 111, 112, 114, 121, Aomori, 30, 34 129, 131, 133–136, 166, 180, 324, Aoyama family, 159 325, 326 Arakawa -

Japanese Spatial Culture, Nature and Architecture

PATTERNS and LAYERING Japanese Spatial Culture, Nature and Architecture Foreword by Kengo KUMA Edited by Salvator-John A. LIOTTA and Matteo BELFIORE PATTERNS and LAYERING Japanese Spatial Culture, Nature and Architecture Foreword: Kengo KUMA Editors: Salvator-John A. LIOTTA Matteo BELFIORE Graphic edition by: Ilze PakloNE Rafael A. Balboa Foreword 4 Kengo Kuma Background 6 Salvator-John A. Liotta and Matteo Belfiore Patterns, Japanese Spatial Culture, Nature, and Generative Design 8 Salvator-John A. Liotta Spatial Layering in Japan 52 Matteo Belfiore Thinking Japanese Pattern Eccentricities 98 Rafael Balboa and Ilze Paklone Evolution of Geometrical Pattern 106 Ling Zhang Development of Japanese Traditional Pattern Under the Influence of Chinese Culture 112 Yao Chen Patterns in Japanese Vernacular Architecture: Envelope Layers and Ecosystem Integration 118 Catarina Vitorino Distant Distances 126 Bojan Milan Končarević European and Japanese Space: A Different Perception Through Artists’ Eyes 134 Federico Scaroni Pervious and Phenomenal Opacity: Boundary Techniques and Intermediating Patterns as Design Strategies 140 Robert Baum Integrated Interspaces: An Urban Interpretation of the Concept of Oku 146 Cristiano Lippa Craft Mediated Designs: Explorations in Modernity and Bamboo 152 Kaon Ko Doing Patterns as Initiators of Design, Layering as Codifier of Space 160 Ko Nakamura and Mikako Koike On Pattern and Digital Fabrication 168 Yusuke Obuchi Foreword Kengo Kuma When I learned that Salvator-John A. Liotta and Matteo Belfiore in my laboratory had launched a study on patterns and layering, I had a premonition of something new and unseen in preexisting research on Japan. Conventional research on Japan has been initiated out of deep affection for Japanese architecture and thus prone to wetness and sentimentality, distanced from the universal and lacking in potential breadth of architectural theories. -

The Abode of Fancy, of Vacancy, and of the Unsymmetrical

The University of Iceland School of Humanities Japanese Language and Culture The Abode of Fancy, of Vacancy, and of the Unsymmetrical How Shinto, Daoism, Confucianism, and Zen Buddhism Interplay in the Ritual Space of Japanese Tea Ceremony BA Essay in Japanese Language and Culture Francesca Di Berardino Id no.: 220584-3059 Supervisor: Gunnella Þorgeirsdóttir September 2018 Abstract Japanese tea ceremony extends beyond the mere act of tea drinking: it is also known as chadō, or “the Way of Tea”, as it is one of the artistic disciplines conceived as paths of religious awakening through lifelong effort. One of the elements that shaped its multifaceted identity through history is the evolution of the physical space where the ritual takes place. This essay approaches Japanese tea ceremony from a point of view that is architectural and anthropological rather than merely aesthetic, in order to trace the influence of Shinto, Confucianism, Daoism, and Zen Buddhism on both the architectural elements of the tea room and the different aspects of the ritual. The structure of the essay follows the structure of the space where the ritual itself is performed: the first chapter describes the tea garden where guests stop before entering the ritual space of the tea room; it also provides an overview of the history of tea in Japan. The second chapter figuratively enters the ritual space of the tea room, discussing how Shinto, Confucianism, Daoism, and Zen Buddhism merged into the architecture of the ritual space. Finally, the third chapter looks at the preparation room, presenting the interplay of the four cognitive systems within the ritual of making and serving tea. -

Shropshire Cover October 2017 .Qxp Shropshire Cover 22/09/2017 14:36 Page 1

Shropshire Cover October 2017 .qxp_Shropshire Cover 22/09/2017 14:36 Page 1 ED GAMBLE AT Your FREE essential entertainment guide for the Midlands HENRY TUDOR HOUSE SHROPSHIRE WHAT’S ON OCTOBER 2017 ON OCTOBER WHAT’S SHROPSHIRE Shropshire ISSUE 382 OCTOBER 2017 ’ WhatFILM I COMEDY I THEATRE I GIGS I VISUAL ARTS I EVENTSs I FOOD On shropshirewhatson.co.uk PART OF WHAT’S ON MEDIA GROUP GROUP MEDIA ON WHAT’S OF PART inside: Yourthe 16-pagelist week by week listings guide stepAUSTENTATIOUS back in time at Theatre Severn TWITTER: @WHATSONSHROPS TWITTER: heavenlyMEGSON music and northern humour at The Hive FACEBOOK: @WHATSONSHROPSHIRE GhostlySPOOK-TASTIC! Gaslight returns to Blists Hill Victorian Town SHROPSHIREWHATSON.CO.UK Day of the Friday 10th November The Buttermarket, Shrewsbury tickets available at Dead thebuttermarket.co.uk Niko's F/P October 2017.qxp_Layout 1 25/09/2017 10:44 Page 1 Contents October Shrops.qxp_Layout 1 22/09/2017 12:23 Page 2 October 2017 Contents Disney On Ice - grab your passport for one big adventure at Genting Arena - more on page 45 Carrie Hope Fletcher Matt Lucas Awful Auntie the list talks about being part of talks about life, from Little David Walliams’ much-loved Your 16-page The Addams Family... Britain to Little Me story arrives on stage week-by-week listings guide feature page 8 interview page 19 page 30 page 53 inside: 4. First Word 11. Food 15. Music 20. Comedy 24. Theatre 39. Film 42. Visual Arts 44. Events @whatsonwolves @whatsonstaffs @whatsonshrops Wolverhampton What’s On Magazine Staffordshire What’s -

Felix Issue 0953, 1993

The Student Newspaper of Imperial College 1 U U 1 il Issue 953 15 January 1993 Imperial Alzheimers Breakthrough by Declan Curry later life. Dr Roberts' team at St. An Imperial researcher has Mary's have been investigating a predicted that a cure for Alzheimers possible link between Alzheimers disease may soon be discovered. Dr disease and head trauma by Gareth Roberts, Senior Lecturer in studying observations from 16 head Anatomy and Cell Biology at St injury cases. Mary's Hospital Medical School, Speaking on IC Radio, Dr was commenting on this week's Roberts said that brain neurons research breakthrough which shows which are first affected by the why and where of the disease. Alzheimers disease tend to contain Alzheimers disease currently more beta amyloid precursor affects almost 350,000 people in the protein than other neurons in United Kingdom. The disease has different parts of the cortex. been known to develop in a person Additional amounts of the protein in their early fifties, and those are produced around the age of above eighty are at a higher risk of fifty, when the neurons undergo developing the dementia. Dr 'resprouting'. Dr Roberts claimed Roberts' research links the onset on that the combination of the the degenerative brain disease with additional protein with the existing head injury and old age. protein 'triggers the disease This week's research focuses on process', and described the the presence in the brain of a small resprouting period as 'the critical molecule known as beta amyloid time for developing the disease'. precursor protein. This protein Dr Roberts said that the research by Gareth Light, problems and would resolve the normally helps repair and maintain had 'pulled together a lot of threads News Editor.