“We'll Embrace One Another and Go On, All Right?” Everyday Life in Ozu

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Space and Narrative in the Films of Ozu1 Kristin

Space and Narrative in the Films of Ozu1 Kristin Thompson David Bordwell Downloaded from The surviving films of Ozu Yasujiro, being only gradually introduced to Western audiences, are already Un'" comfortably assimilated as screen.oxfordjournals.org noble, conservative works. Young j _.ese directors seem to con- sider Ozu's films old-fashioned, while English-language critics' praise their ' beautiful' stories of traditional Japanese family situations. Yet Ozu's films can most productively be read as modernist, inno- vative works. Because no rigorous critical analysis has been per- at Serials Department on May 3, 2011 formed upon Ozu's films (in English), we propose to make a first step by using a method adapted from Russian Formalist poetics. In ' On Literary Evolution ', Tynyanov writes, ' A work is correlated with a particular literary system depending on its deviation, its " difference " as compared with the literary system with which it is confronted ' (L Matejka and K Pomorska, eds: Readings in Russian Poetics, Cambridge, Mass 1971, p 72). In this article we shall situate Ozu's work against a paradigm of ' classical Hollywood cinema'. We have chosen to utilise the paradigm for several reasons: the entity it names coincides intuitively with our familiar sense of what' a film ' is; the paradigm has been explicitly codified by many of its practitioners (eg the host of ' rule-books ' on ' technique'); and the style of the paradigm has, historically, become a pervasive ' ordinary usage ' of the cinema. A background set consisting of this paradigm throws into relief certain stylistic alternatives present in Ozu's films. Though we plan in subsequent 1. -

News Pdf 311.Pdf

2013 World Baseball Classic- The Nominated Players of Team Japan(Dec.3,2012) *ICC-Intercontinental Cup,BWC-World Cup,BAC-Asian Championship Year&Status( A-Amateur,P-Professional) *CL-NPB Central League,PL-NPB Pacific League World(IBAF,Olympic,WBC) Asia(BFA,Asian Games) Other(FISU.Haarlem) 12 Pos. Name Team Alma mater in Amateur Baseball TB D.O.B Asian Note Haarlem 18U ICC BWC Olympic WBC 18U BAC Games FISU CUB- JPN P 杉内 俊哉 Toshiya Sugiuchi Yomiuri Giants JABA Mitsubishi H.I. Nagasaki LL 1980.10.30 00A,08P 06P,09P 98A 01A 12 Most SO in CL P 内海 哲也 Tetsuya Utsumi Yomiuri Giants JABA Tokyo Gas LL 1982.4.29 02A 09P 12 Most Win in CL P 山口 鉄也 Tetsuya Yamaguchi Yomiuri Giants JHBF Yokohama Commercial H.S LL 1983.11.11 09P ○ 12 Best Holder in CL P 澤村 拓一 Takuichi Sawamura Yomiuri Giants JUBF Chuo University RR 1988.4.3 10A ○ P 山井 大介 Daisuke Yamai Chunichi Dragons JABA Kawai Musical Instruments RR 1978.5.10 P 吉見 一起 Kazuki Yoshimi Chunichi Dragons JABA TOYOTA RR 1984.9.19 P 浅尾 拓也 Takuya Asao Chunichi Dragons JUBF Nihon Fukushi Univ. RR 1984.10.22 P 前田 健太 Kenta Maeda Hiroshima Toyo Carp JHBF PL Gakuen High School RR 1988.4.11 12 Best ERA in CL P 今村 猛 Takeshi Imamura Hiroshima Toyo Carp JHBF Seihou High School RR 1991.4.17 ○ P 能見 篤史 Atsushi Nomi Hanshin Tigers JABA Osaka Gas LL 1979.5.28 04A 12 Most SO in CL P 牧田 和久 Kazuhisa Makita Seibu Lions JABA Nippon Express RR 1984.11.10 P 涌井 秀章 Hideaki Wakui Seibu Lions JHBF Yokohama High School RR 1986.6.21 04A 08P 09P 07P ○ P 攝津 正 Tadashi Settu Fukuoka Softbank Hawks JABA Japan Railway East-Sendai RR 1982.6.1 07A 07BWC Best RHP,12 NPB Pitcher of the Year,Most Win in PL P 大隣 憲司 Kenji Otonari Fukuoka Softbank Hawks JUBF Kinki University LL 1984.11.19 06A ○ P 森福 允彦 Mitsuhiko Morifuku Fukuoka Softbank Hawks JABA Shidax LL 1986.7.29 06A 06A ○ P 田中 将大 Masahiro Tanaka Tohoku Rakuten Golden Eagles JHBF Tomakomai H.S.of Komazawa Univ. -

Dragnet Girl

Saturday 15 March | 19:30 Dragnet Girl (Hijôsen No Onna) Dir. Yasujiro Ozu | Japan | 1933 | b/w | 1h 36m Accompanied live by Jane Gardner, Hazel Morrison and Roddy Long Screening supported by Film Hub Scotland, part of BFI’s Film Audience Network Yasujiro Ozu's silent films reveal not just his early mastery of the medium but also the popular basis of his art. One of the greatest of Ozu’s silent films, Dragnet Girl (1933) is a vigorous and stylish work that feels almost casual yet heartfelt. Ozu spins his little story (concocted by himself) of crime, love and redemption with skill while staying close to the concerns of the mass audience of early-1930s Japan, hungry for up-to-date thrills but ambivalent about the changes modernity had brought to the society. For a 21st-century audience that knows Ozu mainly for his later masterworks such as Late Spring (1949), Early Summer (1951) and Tokyo Story (1953), the subject matter of Dragnet Girl may come as a shock. No doubt this melodrama of the criminal underworld appears aberrant in the career of a filmmaker renowned for his elegiac films about middle-class families. The late Donald Richie, a pioneer in Western appreciation of Japanese cinema, mentions Dragnet Girl only fleetingly in his book on Ozu. Even the director himself wrote in his diary that he felt ill at ease working on the film. Ozu has been famously called “the most Japanese of directors,” but Dragnet Girl takes place in a universe that denies Japanese-ness. At the office where the heroine, Tokiko (Kinuyo Tanaka), works during the day, typists use Remington typewriters; at the boxing gym where Tokiko’s boyfriend, Joji (Joji Oka), hangs out and in the apartment the couple share, the walls are covered with posters for American boxing matches and Hollywood films (The Champ and All Quiet on the Western Front); the dance club where Tokiko and Joji spend their nights is conspicuously Western-style. -

El Sable Viene Bajito

Image not found or type unknown www.juventudrebelde.cu Image not found or type unknown De Ichiro Suzuki se echará de menos su experiencia competitiva. Autor: Internet Publicado: 21/09/2017 | 05:28 pm El sable viene bajito Pese a las anunciadas ausencias de sus estrellas «internacionales», el elenco nipón muestra una sólida escuadra de probada calidad Publicado: Domingo 09 diciembre 2012 | 02:18:14 am. Publicado por: Raiko Martín Al equipo de Japón le teme todo el mundo y ese miedo no es gratuito. Viene precedido por los inobjetables títulos conquistados en las únicas dos ediciones del Clásico Mundial de béisbol, y en la capacidad probada de armar un sólida escuadra, aunque no estén disponibles aquellos actualmente enrolados en las Grandes Ligas estadounidenses. Para algunos, las anunciadas ausencias de sus estrellas «internacionales» restan potencia al elenco nipón. Sin embargo, no son pocos los analistas que las asumen como una ventaja, teniendo en cuenta que estas figuras tienden a no seguir el ritmo de trabajo de sus compañeros. La mayoría de los expertos se inclinan a pensar que será el diestro Yu Darvish el que más se extrañe dentro de la nómina, aun cuando tampoco hayan aceptado la invitación notables lanzadores como Hiroki Kuroda y Hisashi Iwakuma. Si hay un área en la que sobre talento dentro, esa es la de los lanzadores. De el icónico Ichiro Suzuki se echará de menos la experiencia y su halo mediático, pero los entendidos señalan al menos cinco jardineros con la capacidad de batear, correr o defender con tanta o mayor calidad que él. -

Cinefiles Document #37926

Document Citation Title Yasujiro Ozu: filmmaker for all seasons Author(s) Source Pacific Film Archive Date 2003 Nov 23 Type program note Language English Pagination No. of Pages 10 Subjects Ozu, Yasujiro (1903-1963), Tokyo, Japan Film Subjects Hitori musuko (The only son), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1936 Shukujo wa nani o wasureta ka (What did the lady forget?), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1937 Todake no kyodai (The brothers and sisters of the Toda family), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1941 Chichi ariki (There was a father), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1942 Nagaya shinshiroku (The record of a tenement gentleman), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1947 Ohayo (Good morning), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1959 Tokyo no yado (An inn at Tokyo), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1935 Hogaraka ni ayume (Walk cheerfully), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1930 Tokyo monogatari (Tokyo story), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1953 WARNING: This material may be protected by copyright law (Title 17 U.S. Code) Dekigokoro (Passing fancy), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1933 Shukujo to hige (The lady and the beard), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1931 Wakaki hi (Days of youth), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1929 Sono yo no tsuma (That night's wife), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1930 Kohayagawa-ke no aki (The end of summer), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1961 Rakudai wa shita keredo (I flunked, but...), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1930 Tokyo no gassho (Tokyo chorus), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1931 Banshun (Late spring), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1949 Seishun no yume ima izuko (Where now are the dreams of youth?), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1932 Munekata shimai (The Munekata sisters), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1950 Hijosen no onna (Dragnet girl), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1933 Ochazuke no aji (The flavor of green tea over rice), Ozu, -

The Moment of Instability: the Textual and Intertextual Analysis of Ozu Yasujiro’S Passing Fancy

〈Research Article〉 The Moment of Instability: The Textual and Intertextual Analysis of Ozu Yasujiro’s Passing Fancy Yuki Takinami Abstract This paper analyzes Ozu Yasujiro’s 1933 film, Passing Fancy (Dekigokoro), in terms of its narrative structure utilizing the minimal narration of repetition and differentiation and the usage of his idiosyncratic shot/reverse shots in which the eyelines of characters are mismatched. This paper also clarifies some references to Hollywood films, such as So, This is Paris, Docks of New York, It, and Marriage Circle, in Passing Fancy and investigates their implications in terms of the moment of instability. Through these examinations, this paper finally addresses the famous debate between Noël Burch and David Bordwell over whether Ozu’s idiosyncratic shot/reverse shots contain a sense of discountinuity, or not. Keywords: Ozu Yasujiro, silent film, narration, shot/reverse shot, Hollywood cinema Passing Fancy (Diekigokoro, 1933) is not a totally neglected film among Ozu Yasujiro’s silent oeuvre, but it is rare for this Kinema junpo Best Film award winner of 1933 to be chosen for detailed discussion, particularly in terms of its aesthetics. 1 However, Ozu in the early 1930s had rapidly developed his aesthetics—as is clear from a brief comparison between his earliest surviving films, such as Days of Youth (Wakaki hi, 1929) and I Flunked But… (Rakudai ha shitakeredo, 1930), and his more integrated and better-wrought films in the mid-1930s, such as Dragnet Girl (Hijosen no onna, 1933) and A Story of Floating Weeds (Ukikusa monogatari, 1934). What, then, had Ozu done in 1933’s Passing Fancy that developed his idiosyncratic film style and narration? What importance does Passing Fancy have in the trajectory of Ozu’s oeuvre? This chapter considers these questions by examining Passing Fancy in terms of (1) Ozu’s minimalist narration, (2) the influence of Hollywood cinema on him, and (3) his usage of eyeline- mismatches and idiosyncratic shot/reverse shots. -

Tokyo Story (Tokyo Monogatari, Yasujiro Ozu, 1953) Discussion Points 1

FAC@JGC John Gray Centre Star Room April 2016 Tokyo Story (Tokyo monogatari, Yasujiro Ozu, 1953) Discussion Points 1. Think about what is at the core (theme) of the story? 2. How does Ozu depict family dynamics in this film – specifically the bond between parents and children? 3. How do you respond to the slow pace of the film? 4. What is your opinion on the portrayal of women in the narrative? 5. What do you think is the effect of presenting: (a) frames in which the camera is right between the two people conversing and films each person directly? (b) so-called tatami shots (the camera is placed as if it were a person kneeling on a tatami mat)? 1 Dr Hanita Ritchie Twitter: @CineFem FAC@JGC John Gray Centre Star Room April 2016 6. How does Ozu present the progression of time in the story? 7. Think about the following translated dialogue between Kyoko, the youngest daughter in the family, and Noriko, the widowed daughter-in-law, after Mrs Hirayama’s death. How would you interpret it in terms of the story as a whole? K: “I think they should have stayed a bit longer.” N: “But they’re busy.” K: “They’re selfish. Demanding things and leaving like this.” N: “They have their own affairs.” K: “You have yours too. They’re selfish. Wanting her clothes right after her death. I felt so sorry for poor mother. Even strangers would have been more considerate.” N: “But look Kyoko. At your age I thought so too. But children do drift away from their parents. -

¡Cuidado Con El Balón

14 DEPORTES DOMINGO 09 DE DICIEMBRE DE 2012 juventud rebelde por JOSÉ LUIS LÓPEZ SADO [email protected] fotos TOMADAS DE INTERNET ¡Cuidado con NO hace falta hacer un sondeo nacional para sentenciar que nuestros jóvenes conocen las particularidades, como deportistas y seres humanos, de sus ídolos futbolísticos, entre los que aparecen Lionel Messi, Cristiano Ronaldo, el balón: es de oro! Andrés Iniesta o Zlatan Ibrahimovic, por solo citar cuatro ejemplos. El próximo 7 de enero, la FIFA dará a conocer quién ganó el Balón Muestra de ello es que a nuestra redacción han llegado correos electrónicos y llamadas telefónicas de jóvenes que de Oro 2012. Hoy, JR comparte con ustedes la historia y actualidad solicitan información sobre la historia del archifamoso Balón de este galardón de Oro, especialmente la rica disputa acerca de quién se lo agenciará este año. ÉRASE UN BALÓN… Según ha trascendido, el Balón de Oro fue un premio indi- vidual otorgado, desde el año 1956 hasta el 2009, por la revista francesa especializada France Football al mejor juga- dor inscrito cada año en algún campeonato de fútbol profe- sional europeo. Por ese motivo también se le conoció como el Premio al mejor jugador europeo del año (European Foot- baller of the Year award). Instituido en 1956 por Gabriel Hanot, director de la men- cionada revista y precursor de la Copa de Campeones de Europa, en un principio el galardón estuvo dirigido exclusiva- mente a futbolistas de nacionalidad europea. El primer gana- dor fue el inglés Stanley Matthews, quien ese año jugaba para el Blackpool Football Club. -

Ka As Shomin-Geki: Problematizing Videogame Studies William Huber 34 Rausch Street 401 San Francisco, CA 94103 USA +1 415 861 5863 [email protected]

Ka as shomin-geki: Problematizing videogame studies William Huber 34 Rausch Street 401 San Francisco, CA 94103 USA +1 415 861 5863 [email protected] ABSTRACT The paper addresses limitations of strictly interactive theories of videogame genre, proposes a supplementary, historicist inter-media alternative, and interprets the videogame Ka as a ludic worked based in the shomin-geki tradition of Japanese cinema. Keywords Japanese cultural history, videogame genre theory, shomin-geki, domesticity, intertextuality Rather than looking at videogames in general, this paper examines one game in particular as a cultural artifact: Ka, produced in Japan in 2001, and later released in the US and Europe as Mister Mosquito. By bringing a historicist sensibility to the study of individual games in the aftermath of the initial ludology/narratology formalist discussions, the purpose of this paper is to demonstrate a way to access videogames as texts in ways that recognize their inherent, media-specific structure as videogames, yet also explore their inevitable intertextualities. To begin with, I look at some general aspects of genre theory as they affect the study of games. I then turn to the game itself, breaking out the structure in a table of interactive and narrative events. An explanation of the shomin-geki comedy drama follows, with attention to how the texts of that genre react to historical changes in the discursive field it tracks, ultimately to include Ka in its concern with the ongoing construction of domesticity in Japan. By tracking genre-formation to historical anxieties within cultural practice, and seeing game-texts as participants in intertextual, thematic genres, we can better understand how they generate discursive positions within gameplay. -

100 Jahre Ozu 100 Years Ozu

5 100 Jahre Ozu 100 Years Ozu Aus Anlass des 100. Geburtstages (im Dezember 2003) des japani- To mark the 100th anniversary (in December 2003) of the schen Filmregisseurs Ozu Yasujiro (1903-1963) hat die Produktionsge- birth of Japanese film director Ozu Yasujiro (1903-1963), sellschaft Shochiku, für die Ozu zeitlebens tätig war und die meisten the Shochiku production company – for which Ozu worked seiner Filme drehte, alle noch erhaltenen Ozu-Filme ihrer eigenen throughout his life and where he shot most of his films – Produktion aus den Jahren 1927-1962 neu englisch untertitelt und struck new prints of all surviving Ozu films that it produced auf gutes Kopienmaterial gebracht; diese dreiunddreißig Filme wur- between 1927 and 1962 and had them subtitled anew in den zu einer Werkschau zusammengestellt, die auf der Berlinale 2003 English. These 33 films have been put together into a show- ihre Uraufführung erlebt. Neun Ozu-Filme laufen auf der Berlinale, case of the director’s work which will premiere at the 2003 darunter vier im Programm des Forums; die Retrospektive wird an- Berlin Film Festival. Nine Ozu films will be shown at the schließend an die Berlinale im Arsenal (bis Ende März 2003) mit einer Berlinale, four of them in the Forum programme. The retro- nochmaligen kompletten Übersicht über alle erhaltenen Ozu-Filme fort- spective will then continue at the Arsenal cinema after the gesetzt. festival ends (and until late March 2003), providing an- Aus Anlass der großen Ozu-Retrospektive erscheint bei den Freunden other complete overview of all the available Ozu films. der Deutschen Kinemathek in der Reihe ‘Kinemathek‘ ein Ozu Yasujiro On the occasion of the big Ozu retrospective, the Friends gewidmetes Heft, das auf 192 Seiten Beiträge zum Werk und zur of the German Film Archive have produced a book dedi- Person Ozus präsentiert sowie eine kommentierte Aufstellung sämtli- cated to Ozu Yasujiro as part of their ‘Kinemathek’ series. -

AN AUTUMN AFTERNOON (Sanma No Aji) Directed by Yasujiro Ozu Japan, 1962, 112 Mins, Cert PG

AN AUTUMN AFTERNOON (Sanma no aji) Directed by Yasujiro Ozu Japan, 1962, 112 mins, Cert PG With Chishu Ryu, Shima Iwashita, Keiji Sada, Mariko Okada New 2K restoration Opening on 16 May 2014 at BFI Southbank and selected cinemas nationwide 17/3/14 – Now ravishingly restored by Shochiku Studios, Japan’s National Film Centre and the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, An Autumn Afternoon is the final work of Japanese master filmmaker Yasujiro Ozu (1903 – 1963). One of the greatest last films in all of cinema history, it is released by the BFI in cinemas nationwide on 16 May. While the film’s original Japanese title (which translates as ‘The Taste of Mackerel’) is less obviously elegiac than its English one, Ozu’s masterpiece is truly autumnal, charting the inevitable eclipse of older generations by irreverent youth. Revisiting the storyline of his earlier Late Spring (1949), Ozu collaborates once more with his regular screenwriter Kogo Noda and casts the familiar face of Chishu Ryu in the role of Hirayama, an elderly widower worried about the unmarried daughter who keeps house for him. Counselled on all sides to marry her off before it is too late, Hirayama plays matchmaker and reluctantly prepares to bid his old life farewell. The themes throughout are familiar from much of the director’s greatest work: everyday life with all its ups and downs – at home, at work, in local bars, with family, with old friends. These are ordinary people whose stories may not have big melodramatic moments, but whose concerns – loneliness, ageing parents, family responsibility – resonate deeply with us all. -

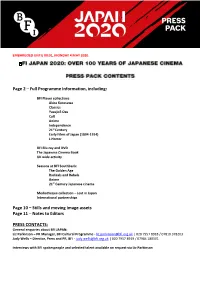

Notes to Editors PRESS

EMBARGOED UNTIL 00:01, MONDAY 4 MAY 2020. Page 2 – Full Programme Information, including: BFI Player collections Akira Kurosawa Classics Yasujirō Ozu Cult Anime Independence 21st Century Early Films of Japan (1894-1914) J-Horror BFI Blu-ray and DVD The Japanese Cinema Book UK wide activity Seasons at BFI Southbank: The Golden Age Radicals and Rebels Anime 21st Century Japanese cinema Mediatheque collection – Lost in Japan International partnerships Page 10 – Stills and moving image assets Page 11 – Notes to Editors PRESS CONTACTS: General enquiries about BFI JAPAN: Liz Parkinson – PR Manager, BFI Cultural Programme - [email protected] | 020 7957 8918 / 07810 378203 Judy Wells – Director, Press and PR, BFI - [email protected] | 020 7957 8919 / 07984 180501 Interviews with BFI spokespeople and selected talent available on request via Liz Parkinson FULL PROGRAMME HIGHLIGHTS EMBARGOED UNTIL 00:01, MONDAY 4 MAY 2020. BFI PLAYER COLLECTIONS The BFI’s VOD service BFI Player will be the premier destination for Japanese film this year with thematic collections launching over a six month period (May – October): Akira Kurosawa (11 May), Classics (11 May), Yasujirō Ozu (5 June), Cult (3 July), Anime (31 July), Independence (21 August), 21st Century (18 September) and J-Horror (30 October). All the collections will be available to BFI Player subscribers (£4.99 a month), with a 14 day free trial available to new customers. There will also be a major new free collection Early Films of Japan (1894-1914), released on BFI Player on 12 October, featuring material from the BFI National Archive’s significant collection of early films of Japan dating back to 1894.