Space and Narrative in the Films of Ozu1 Kristin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“We'll Embrace One Another and Go On, All Right?” Everyday Life in Ozu

“We’ll embrace one another and go on, all right?” Everyday life in Ozu Yasujirô’s post-war films 1947-1949. University of Turku Faculty of Humanities Cultural History Master’s thesis Topi E. Timonen 17.5.2019 The originality of this thesis has been checked in accordance with the University of Turku quality assurance system using the Turnitin OriginalityCheck service. UNIVERSITY OF TURKU School of History, Culture and Arts Studies Faculty of Humanities TIMONEN, TOPI E.: “We’ll embrace one another and go on, all right?” Everyday life in Ozu Yasujirô’s post-war films 1947-1949. Master’s thesis, 84 pages. Appendix, 2 pages. Cultural history May 2019 Summary The subject of my master’s thesis is the depiction of everyday life in the post-war films of Japanese filmmaker Ozu Yasujirô (1903-1963). My primary sources are his three first post- war films: Record of a Tenement Gentleman (Nagaya shinshiroku, 1947), A Hen in the Wind (Kaze no naka no mendori, 1948) and Late Spring (Banshun, 1949). Ozu’s aim in his filmmaking was to depict the Japanese people, their society and their lives in a realistic fashion. My thesis offers a close reading of these films that focuses on the themes that are central in their everyday depiction. These themes include gender roles, poverty, children, nostalgia for the pre-war years, marital equality and the concept of arranged marriage, parenthood, and cultural juxtaposition between Japanese and American influences. The films were made under American censorship and I reflect upon this context while examining the presentation of the themes. -

Cinefiles Document #37926

Document Citation Title Yasujiro Ozu: filmmaker for all seasons Author(s) Source Pacific Film Archive Date 2003 Nov 23 Type program note Language English Pagination No. of Pages 10 Subjects Ozu, Yasujiro (1903-1963), Tokyo, Japan Film Subjects Hitori musuko (The only son), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1936 Shukujo wa nani o wasureta ka (What did the lady forget?), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1937 Todake no kyodai (The brothers and sisters of the Toda family), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1941 Chichi ariki (There was a father), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1942 Nagaya shinshiroku (The record of a tenement gentleman), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1947 Ohayo (Good morning), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1959 Tokyo no yado (An inn at Tokyo), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1935 Hogaraka ni ayume (Walk cheerfully), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1930 Tokyo monogatari (Tokyo story), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1953 WARNING: This material may be protected by copyright law (Title 17 U.S. Code) Dekigokoro (Passing fancy), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1933 Shukujo to hige (The lady and the beard), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1931 Wakaki hi (Days of youth), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1929 Sono yo no tsuma (That night's wife), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1930 Kohayagawa-ke no aki (The end of summer), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1961 Rakudai wa shita keredo (I flunked, but...), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1930 Tokyo no gassho (Tokyo chorus), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1931 Banshun (Late spring), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1949 Seishun no yume ima izuko (Where now are the dreams of youth?), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1932 Munekata shimai (The Munekata sisters), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1950 Hijosen no onna (Dragnet girl), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1933 Ochazuke no aji (The flavor of green tea over rice), Ozu, -

Tokyo Story (Tokyo Monogatari, Yasujiro Ozu, 1953) Discussion Points 1

FAC@JGC John Gray Centre Star Room April 2016 Tokyo Story (Tokyo monogatari, Yasujiro Ozu, 1953) Discussion Points 1. Think about what is at the core (theme) of the story? 2. How does Ozu depict family dynamics in this film – specifically the bond between parents and children? 3. How do you respond to the slow pace of the film? 4. What is your opinion on the portrayal of women in the narrative? 5. What do you think is the effect of presenting: (a) frames in which the camera is right between the two people conversing and films each person directly? (b) so-called tatami shots (the camera is placed as if it were a person kneeling on a tatami mat)? 1 Dr Hanita Ritchie Twitter: @CineFem FAC@JGC John Gray Centre Star Room April 2016 6. How does Ozu present the progression of time in the story? 7. Think about the following translated dialogue between Kyoko, the youngest daughter in the family, and Noriko, the widowed daughter-in-law, after Mrs Hirayama’s death. How would you interpret it in terms of the story as a whole? K: “I think they should have stayed a bit longer.” N: “But they’re busy.” K: “They’re selfish. Demanding things and leaving like this.” N: “They have their own affairs.” K: “You have yours too. They’re selfish. Wanting her clothes right after her death. I felt so sorry for poor mother. Even strangers would have been more considerate.” N: “But look Kyoko. At your age I thought so too. But children do drift away from their parents. -

AN AUTUMN AFTERNOON (Sanma No Aji) Directed by Yasujiro Ozu Japan, 1962, 112 Mins, Cert PG

AN AUTUMN AFTERNOON (Sanma no aji) Directed by Yasujiro Ozu Japan, 1962, 112 mins, Cert PG With Chishu Ryu, Shima Iwashita, Keiji Sada, Mariko Okada New 2K restoration Opening on 16 May 2014 at BFI Southbank and selected cinemas nationwide 17/3/14 – Now ravishingly restored by Shochiku Studios, Japan’s National Film Centre and the National Museum of Modern Art, Tokyo, An Autumn Afternoon is the final work of Japanese master filmmaker Yasujiro Ozu (1903 – 1963). One of the greatest last films in all of cinema history, it is released by the BFI in cinemas nationwide on 16 May. While the film’s original Japanese title (which translates as ‘The Taste of Mackerel’) is less obviously elegiac than its English one, Ozu’s masterpiece is truly autumnal, charting the inevitable eclipse of older generations by irreverent youth. Revisiting the storyline of his earlier Late Spring (1949), Ozu collaborates once more with his regular screenwriter Kogo Noda and casts the familiar face of Chishu Ryu in the role of Hirayama, an elderly widower worried about the unmarried daughter who keeps house for him. Counselled on all sides to marry her off before it is too late, Hirayama plays matchmaker and reluctantly prepares to bid his old life farewell. The themes throughout are familiar from much of the director’s greatest work: everyday life with all its ups and downs – at home, at work, in local bars, with family, with old friends. These are ordinary people whose stories may not have big melodramatic moments, but whose concerns – loneliness, ageing parents, family responsibility – resonate deeply with us all. -

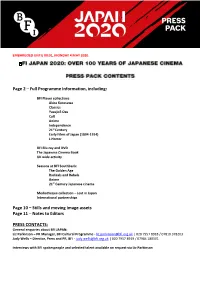

Notes to Editors PRESS

EMBARGOED UNTIL 00:01, MONDAY 4 MAY 2020. Page 2 – Full Programme Information, including: BFI Player collections Akira Kurosawa Classics Yasujirō Ozu Cult Anime Independence 21st Century Early Films of Japan (1894-1914) J-Horror BFI Blu-ray and DVD The Japanese Cinema Book UK wide activity Seasons at BFI Southbank: The Golden Age Radicals and Rebels Anime 21st Century Japanese cinema Mediatheque collection – Lost in Japan International partnerships Page 10 – Stills and moving image assets Page 11 – Notes to Editors PRESS CONTACTS: General enquiries about BFI JAPAN: Liz Parkinson – PR Manager, BFI Cultural Programme - [email protected] | 020 7957 8918 / 07810 378203 Judy Wells – Director, Press and PR, BFI - [email protected] | 020 7957 8919 / 07984 180501 Interviews with BFI spokespeople and selected talent available on request via Liz Parkinson FULL PROGRAMME HIGHLIGHTS EMBARGOED UNTIL 00:01, MONDAY 4 MAY 2020. BFI PLAYER COLLECTIONS The BFI’s VOD service BFI Player will be the premier destination for Japanese film this year with thematic collections launching over a six month period (May – October): Akira Kurosawa (11 May), Classics (11 May), Yasujirō Ozu (5 June), Cult (3 July), Anime (31 July), Independence (21 August), 21st Century (18 September) and J-Horror (30 October). All the collections will be available to BFI Player subscribers (£4.99 a month), with a 14 day free trial available to new customers. There will also be a major new free collection Early Films of Japan (1894-1914), released on BFI Player on 12 October, featuring material from the BFI National Archive’s significant collection of early films of Japan dating back to 1894. -

From Screen to Page: Japanese Film As a Historical Document, 1931-1959

FROM SCREEN TO PAGE: JAPANESE FILM AS A HISTORICAL DOCUMENT, 1931-1959 by Olivia Umphrey A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Boise State University May 2009 © 2009 Olivia Umphrey ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BOISE STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COLLEGE DEFENSE COMMITTEE AND FINAL READING APPROVALS of the thesis submitted by Olivia Anne Umphrey Thesis Title: From Screen to Page: Japanese Film as a Historical Document, 1931- 1959 Date of Final Oral Examination: 03 April 2009 The following individuals read and discussed the thesis submitted by student Stephanie Stacey Starr, and they also evaluated her presentation and response to questions during the final oral examination. They found that the student passed the final oral examination, and that the thesis was satisfactory for a master’s degree and ready for any final modifications that they explicitly required. L. Shelton Woods, Ph.D. Chair, Supervisory Committee Lisa M. Brady, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee Nicanor Dominguez, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee The final reading approval of the thesis was granted by L. Shelton Woods, Ph.D., Chair of the Supervisory Committee. The thesis was approved for the Graduate College by John R. Pelton, Ph.D., Dean of the Graduate College. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author wishes to thank her advisor, Dr. Shelton Woods, for his guidance and patience, as well as her committee members, Dr. Lisa Brady and Dr. Nicanor Dominguez, for their insights and assistance. iv ABSTRACT This thesis explores to what degree Japanese film accurately reflects the scholarly accounts of Japanese culture and history. -

Trashionals 12 Round 8 Toss-Ups

TRASHionals 12 Round 8 Toss-Ups 1. This man's gravesite is inscribed with the character "Mu." Early films made by him include the gangster drama Dragnet Girl and a comedy about mischievous children called I Was Born, But .... His works in color, like Equinox Flower, Good Morning, The End of Summer, and An Autumn Afternoon, show an obsession with symmetrical composition and an almost total absence of camera tracking. Also known for his use of "pillow shots," he frequently worked with Chishu Ryu and Setsuko Hara on such family dramas as Floating Weeds, Late Spring, and Late Autumn, and well as his masterpiece, which climaxes with the question, "Isn't life disappointing?" for ten points, name this Japanese director of Tokyo Story. Answer: Yasujiro Ozu 2. Tonya Antonucci was named its commissioner in September 2007, fitting as she was the CEO of the corporation it was founded from. Teams are owned by local investors and notables like Yahoo president Jeff Mallett and NBAer Steve Nash. Puma has an exclusive deal to outfit the teams and provide all equipment, including the game ball. It plans to expand into Atlanta and Philadelphia in 2010, complimenting its five new teams and two carry overs from a previous league. It opened play on March 29, with the Los Angeles Sol squaring off against one of the surviving WUSA teams, the Washington Freedom. With other new teams like FC Gold Pride and St. Louis Athletica, name for ten points, this new top-level association football league for females. Answer: Women's Professional Soccer 3. -

JAPANESE CINEMA DONALD Eichie Has Lodg Been the Internationally Acclaimed Expert on the Japanese Film

JAPANESE CINEMA DONALD EiCHiE has loDg been the internationally acclaimed expert on the Japanese film. He is a former member of Uni- Japan Film and film critic for The Japan Times, and is pres- ently Curator of the Film Department at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. He designed and presented the Kurosawa and Ozu retrospectives, as well as the massive 1970 retrospective at the museum, The Japanese Film. His book on The Films of Akira Kurosawa has been called a "virtual model for future studies in the field." Mr. Richie has been a resident of Japan for the past twenty-five years. Film books by Donald Richie: The Cinematographic View: A Study of the Film. 1958. The Japanese Film: Art and Industry. 1959. Co-authored with Joseph L. Anderson. Japanese Movies. 1961. The Japanese Movie: An Illustrated History. 1965. The Films of Akira Kurosawa. 1965. George Stevens: An American Romantic. 1970. Japanese Cine2wa Film Style and National Character Donald Ricliie Anchor Books DOUBLEDAY & COMPANY, INC., GABDKN CTTY, NEW YORK This book is an extensively revised, expanded, and updated version of Japanese Movies, © 1961 by Japan Travel Bureau. Original material reprinted by pemMSsion of the Japan Travel Bureau, Inc., Japan. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 77-163122 Copyright © 1971 by Donald Richie Copyright © 1961 by Japan Travel Bureau All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States of America CONTENTS List of Illiistrations vii Introduction xvii 1896-1945 1 194&-1971 59 Appendix 239 Index 250 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS The Abe Clan, 1938. 29 An Actor's Revenge, 1963. -

The Golden Era of Japanesa Cinema

THE GOLDEN ERA OF JAPANESE CINEMA The 1950s are widely considered the Golden Age of Japanese cinema. Three Japanese films from this decade made the Sight & Sound's 2002 Critics and Directors Poll for the best films of all time. Rashomon Seven Samurai Tokyo Story The period after the American Occupation led to a rise in diversity in movie distribution thanks to the increased output and popularity of the film studios: Toho Daiei Shochiku Nikkatsu Toei This period gave rise to the four great directors of Japanese cinema: Masaki Kobayashi Akira Kurosawa Kenji Mizoguchi Yasujirō Ozu. Two types of dramas Gendai–Geki : Contemporary Drama/Social Issues Jidai-Geki: Costume or Period Drama (Samurai Films) TIME LINE: 1946 - The Civil Censorship Department was created within the Civil Intelligence Section of the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers. It exercised considerable influence over the operation and administration of the American Occupation of Japan after World War II. Bans 31 Separate topics from films – including imperial propaganda (i.e. Samurai Films) 1948 – US vs Paramount. The beginning the end for the studio system. 1949 November- The Civil Censorship Department becomes less heavy handed. 1950 - The decade started with Akira Kurosawa's Rashomon (1950), which won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival in 1951 and the Academy Award for Best Foreign Language Film in 1952, and marked the entrance of Japanese cinema onto the world stage. It was also the breakout role for legendary star Toshiro Mifune. 1950 - The Blue Ribbon Awards were established in 1950. The first winner for Best Film was Until We Meet Again by Tadashi Imai. -

Ainu Ethnobiology

Williams Ainu Ethnobiology In the last 20 years there has been an increasing focus on study of Ainu culture in Japan, the United States, and in Europe. is has resulted in a number of major exhibitions and publications such as “Ainu, Spirit of a Northern People” published in 1999 by the Ainu Ethnobiology Smithsonian and the University of Washington Press. While such e orts have greatly enhanced our general knowledge of the Ainu, they did not allow for a full understanding of the way in which the Ainu regarded and used plants and animals in their daily life. is study aims at expanding our knowledge of ethnobiology as a central component of Ainu culture. It is based in large part on an analysis of the work of Ainu, Japanese, and Western researchers working in the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries. Ainu Ethnobiology Dai Williams was born in Lincoln, England in 1941. He received a BA in Geography and Anthropology from Oxford University in 1964 and a MA in Landscape Architecture from the University of Pennsylvania in 1969. He spent the majority of his career in city and regional planning. His cultural research began through museum involvement in the San Francisco Bay Area. Based in Kyoto from 1989, he began research on the production and use of textiles in 19th century rural Japan. His research on the Ainu began in 1997 but primarily took place in Hokkaido between 2005 and 2009. Fieldwork focused on several areas of Hokkaido, like the Saru River Basin and the Shiretoko Peninsula, which the Ainu once occupied. -

Dvd Press Release

DVD & Blu-ray press release More Yasujiro Ozu Dual Format Edition releases from the BFI on 23 May 2011 On 23 May the BFI adds more titles to its ongoing strand, The Ozu Collection with the release of Late Autumn (1960) and An Autumn Afternoon (1962). Presented in Dual Format Editions (a Blu-ray and a DVD disc in one box), each main feature is complemented by an early Ozu film that has never been made available in the UK before. The Ozu Collection, which will eventually feature all 32 of the world-renowned Japanese director’s surviving films made for the Shochiku Studio, already contains Tokyo Story, Early Summer, Late Spring, Equinox Flower and Good Morning. Late Autumn (Akibiyori) & A Mother Should be Loved (Haha O Kowazuya) When college nostalgia inspires a group of middle-aged businessmen to match-make for the widow of a friend – played with measured dignity by Setsuko Hara (Tokyo Story) – and her daughter, they have no idea of the strife their careless interference will cause. Late Autumn’s examination of familial upheaval moves effortlessly from comedy to pathos and is amongst the finest of Ozu’s post-war films. Also included here is surviving version of Ozu’s moving silent drama A Mother Should be Loved. Missing both first and last reels, the incomplete film nevertheless achieves a dramatic intensity in its portrayal of a young man struggling to deal with a disturbing family secret. It is presented with an alternative, newly commissioned, score by composer Ed Hughes. Special features Standard Definition and High Definition presentations of Late Autumn (DVD & Blu-ray) Standard Definition presentation of A Mother Should be Loved Optional score for A Mother Should be Loved by Ed Hughes, commissioned exclusively for the BFI Illustrated booklet with a new sleevenote essay by Asian cinema expert Alexander Jacoby New and improved English subtitles An Autumn Afternoon (Sanma No Aji) & A Hen in the Wind (Kaze No Naka No Mendori) Yasujiro Ozu’s elegiac final film An Autumn Afternoon charts the inevitable eclipse of older generations by irreverent youth. -

Ozu and World Cinema Daisuke Miyao Postdoctoral Fellow, Film

EAAS V3317: Ozu and World Cinema Daisuke Miyao Postdoctoral Fellow, Film Studies, University of California, Berkeley First offered as an ExEAS course at Columbia University in Fall 2003 Class Meetings: Monday & Wednesday 4:10-5:25 Screenings: Monday 6:10- 1. Course Description: Since the1960s, Japanese director Yasujiro Ozu (1903-1963) has been the object of increased popular and critical attention by international film scholars and audiences. Ozu is widely considered “the most Japanese” of Japanese directors, but what does “the most Japanese” mean? Do Ozu’s films express the special characteristics of Japanese cinema? If so, what constitutes the cultural specificity of Japanese cinema? At the same time, Ozu was a big fan of foreign films. The director considered “the most Japanese” was in fact steeped in foreign popular culture. How can Ozu be located in global film cultures and international histories of cinema? This course reexamines Ozu’s works in terms of their social and cultural context, from both national and transnational perspectives. It locates Ozu’s films at a dialogic focal point of Japanese, American and European cinema. Through an intense examination of Ozu’s films as primary texts, this course pays particular attention to Japanese modernization in the 1920s; the influence of wartime film policy; reconfiguration of traditional Japanese art forms during the postwar Occupation; the decline of the Japanese film studio system and the popularization of international film festivals. We will also discuss the mutual influence between American and European cinema and Ozu’s films and Ozu’s legacy in international films, including New German Cinema (Wim Wenders), American independent films (Jim Jarmusch), and contemporary Japanese films (Kiju Yoshida, Masayuki Suo).