Mid-August Lunch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“We'll Embrace One Another and Go On, All Right?” Everyday Life in Ozu

“We’ll embrace one another and go on, all right?” Everyday life in Ozu Yasujirô’s post-war films 1947-1949. University of Turku Faculty of Humanities Cultural History Master’s thesis Topi E. Timonen 17.5.2019 The originality of this thesis has been checked in accordance with the University of Turku quality assurance system using the Turnitin OriginalityCheck service. UNIVERSITY OF TURKU School of History, Culture and Arts Studies Faculty of Humanities TIMONEN, TOPI E.: “We’ll embrace one another and go on, all right?” Everyday life in Ozu Yasujirô’s post-war films 1947-1949. Master’s thesis, 84 pages. Appendix, 2 pages. Cultural history May 2019 Summary The subject of my master’s thesis is the depiction of everyday life in the post-war films of Japanese filmmaker Ozu Yasujirô (1903-1963). My primary sources are his three first post- war films: Record of a Tenement Gentleman (Nagaya shinshiroku, 1947), A Hen in the Wind (Kaze no naka no mendori, 1948) and Late Spring (Banshun, 1949). Ozu’s aim in his filmmaking was to depict the Japanese people, their society and their lives in a realistic fashion. My thesis offers a close reading of these films that focuses on the themes that are central in their everyday depiction. These themes include gender roles, poverty, children, nostalgia for the pre-war years, marital equality and the concept of arranged marriage, parenthood, and cultural juxtaposition between Japanese and American influences. The films were made under American censorship and I reflect upon this context while examining the presentation of the themes. -

Yasujiro OZU

Yasujiro OZU Le cinéaste japonais de l’humanisme Iconographie : ©Studios SHOCHIKU et Internet Des plans fixes, presque au ras du sol, filmant très sobrement des scènes de la vie si criantes de vérité qu’on se croirait membre d’une famille japonaise dans les années 1940-60, telle est la marque de fabrique de ce maître mondial du cinéma moderne japonais, Ozu. « Bonjour », « Le goût du saké », « Fleurs d’équinoxe », au charme lancinant si marquant, à l’équilibre sobre des dialogues et des contextes: ces titres, parmi tant d’autres, auront marqué des générations entières de cinéphiles, incluant l’auteur de ces lignes. Il est mort bien jeune, à la soixantaine pile, nous laissant 36 œuvres encore disponibles sur les plus de 50 qu’il a créées, car certains originaux ont disparu avec leurs négatifs dans les aléas de l’après-guerre des années 1940, tout bêtement. Il aura été le cinéaste nous donnant une vision vraie, humaine, et juste de la société japonaise de son époque. La disponibilité actuelle en France de 2 packs vidéo de 5 DVD chacun de ses films constitue une vraie aubaine, pour ceux qui ne connaîtraient pas encore ce maître du cinéma japonais faisant partie de la trilogie fameuse que forment ces légendes au nom illustre: Mizoguchi, Kurosawa, et naturellement lui-même, Ozu. A une différence, cependant : alors que les 2 autres dépeignent des personnages parfois historiques dans des situations souvent shakespeariennes (plus Kurosawa que Mizoguchi par ailleurs), Ozu se contente de dépeindre des gens simples de la société civile japonaise moderne dans des contextes totalement quotidiens. -

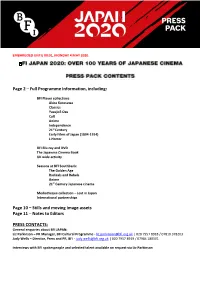

Notes to Editors PRESS

EMBARGOED UNTIL 00:01, MONDAY 4 MAY 2020. Page 2 – Full Programme Information, including: BFI Player collections Akira Kurosawa Classics Yasujirō Ozu Cult Anime Independence 21st Century Early Films of Japan (1894-1914) J-Horror BFI Blu-ray and DVD The Japanese Cinema Book UK wide activity Seasons at BFI Southbank: The Golden Age Radicals and Rebels Anime 21st Century Japanese cinema Mediatheque collection – Lost in Japan International partnerships Page 10 – Stills and moving image assets Page 11 – Notes to Editors PRESS CONTACTS: General enquiries about BFI JAPAN: Liz Parkinson – PR Manager, BFI Cultural Programme - [email protected] | 020 7957 8918 / 07810 378203 Judy Wells – Director, Press and PR, BFI - [email protected] | 020 7957 8919 / 07984 180501 Interviews with BFI spokespeople and selected talent available on request via Liz Parkinson FULL PROGRAMME HIGHLIGHTS EMBARGOED UNTIL 00:01, MONDAY 4 MAY 2020. BFI PLAYER COLLECTIONS The BFI’s VOD service BFI Player will be the premier destination for Japanese film this year with thematic collections launching over a six month period (May – October): Akira Kurosawa (11 May), Classics (11 May), Yasujirō Ozu (5 June), Cult (3 July), Anime (31 July), Independence (21 August), 21st Century (18 September) and J-Horror (30 October). All the collections will be available to BFI Player subscribers (£4.99 a month), with a 14 day free trial available to new customers. There will also be a major new free collection Early Films of Japan (1894-1914), released on BFI Player on 12 October, featuring material from the BFI National Archive’s significant collection of early films of Japan dating back to 1894. -

小津安二郎ありき Ozu Yasujirō Retrospective at Yale University

小津安二郎ありき Ozu Yasujirō Retrospective at Yale University September 19 – November 13, 2008 Presented by the Council on East Asian Studies at Yale University and the Cinema at the Whitney We are very pleased to be able to present thirteen films by one of the world’s most renowned film directors, Ozu Yasujirō. Among the trio of great Japanese cinema masters, Ozu, Kurosawa Akira, and Mizoguchi Kenji, Ozu was the last to be introduced abroad (largely after his death in 1963), yet is now arguably the most celebrated. His Tokyo Story was selected as the fifth best film of all time in Sight and Sound’s illustrious poll of world critics in 2002, and a legion of directors, from Wim Wenders to Hou Hsiao-hsien, have professed their admiration and influence. With the celebration of the centenary of his birth in 2003, there are still studies on Ozu coming out, including a translation or the director Yoshida Yoshishige’s marvelous Ozu’s Anti-Cinema (Ann Arbor: Center for Japanese Studies, University of Michigan, 2003), in which the New Wave director who once criticized his studio elder, re-appraises him forty years later. There is a veritable cottage industry of books on him in Japan. Why does Ozu still fascinate us after so many years? In some ways, it is because his films are so versatile and can speak to multiple perspectives and multiple generations. To some, he is the most Japanese of directors, depicting the sweet pathos of family life through a still camera that remains close to the floor, like a Japanese guest sitting on a tatami mat. -

From Screen to Page: Japanese Film As a Historical Document, 1931-1959

FROM SCREEN TO PAGE: JAPANESE FILM AS A HISTORICAL DOCUMENT, 1931-1959 by Olivia Umphrey A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Boise State University May 2009 © 2009 Olivia Umphrey ALL RIGHTS RESERVED BOISE STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE COLLEGE DEFENSE COMMITTEE AND FINAL READING APPROVALS of the thesis submitted by Olivia Anne Umphrey Thesis Title: From Screen to Page: Japanese Film as a Historical Document, 1931- 1959 Date of Final Oral Examination: 03 April 2009 The following individuals read and discussed the thesis submitted by student Stephanie Stacey Starr, and they also evaluated her presentation and response to questions during the final oral examination. They found that the student passed the final oral examination, and that the thesis was satisfactory for a master’s degree and ready for any final modifications that they explicitly required. L. Shelton Woods, Ph.D. Chair, Supervisory Committee Lisa M. Brady, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee Nicanor Dominguez, Ph.D. Member, Supervisory Committee The final reading approval of the thesis was granted by L. Shelton Woods, Ph.D., Chair of the Supervisory Committee. The thesis was approved for the Graduate College by John R. Pelton, Ph.D., Dean of the Graduate College. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author wishes to thank her advisor, Dr. Shelton Woods, for his guidance and patience, as well as her committee members, Dr. Lisa Brady and Dr. Nicanor Dominguez, for their insights and assistance. iv ABSTRACT This thesis explores to what degree Japanese film accurately reflects the scholarly accounts of Japanese culture and history. -

Tokyo Story Are Donald Richie, Ozu (1977); David Bordwell, Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema (Rep

October 22, 2002 (VI:9) Conversations about great films with Diane Christian & Bruce Jackson Yasujiro Ozu (12 December 1903, Tokyo—12 December 1963, Tokyo, cancer) directed 54 films, only 33 of which still exist. His work wasn't much known in the west until the 1960s. His last film was Sanma no aji/An Autumn Afternoon (1962); his first Zange no yaiba/Sword of Penitence (1927); the best known is Ukigusa (1959, US Floating Weeds 1970). Some of the others are Umarete wa mita keredo/I was Born But... 1932, Tokyo no onna/A Woman of Tokyo 1933, Nagaya shinshiroku/Record of a Tenement Gentleman 1947, Banshun/Late Spring 1949, Bakushu/Early Summer 1951, Higanbana/Equinox Flower 1958, Ohayo/Good Morning 1959 and Sanma no aji 1962. The best published texts on Ozu's life and work and Tokyo Story are Donald Richie, Ozu (1977); David Bordwell, Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema (rep. 1994); David Dresser, Ed., Ozu's Tokyo Story (Cambridge Film Handbooks Series, 1997); and Paul Schrader, Transcendental Style in Film : Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer rep. 1988).On the web: The University of Tokyo maintains "Behind the Camera,"an excellent site on Ozu and his cameraman on Tokyo Story, with a lot of analysis, samples from the cameraman's notebooks, and more: http://www.um.u-tokyo.ac.jp/dm2k-umdb/publish_db/books/ozu/ Another good web site on his life and workis http://homepage.mac.com/kwoy/ozu/ozu.htm. from World Film Directors. V.I. Ed. John Wakeman. H.W. Wilson Co. NY 1987 Notoriously hard-working in later years, Ozu enjoyed his stint as an In the course of his career, Ozu would receive six Kinema assistant director primarily because he “could drink all I wanted and Jumpo “best ones,” more than any other director in the history of spend my time talking.” He was nevertheless promoted before the end Japanese cinema. -

JAPANESE CINEMA DONALD Eichie Has Lodg Been the Internationally Acclaimed Expert on the Japanese Film

JAPANESE CINEMA DONALD EiCHiE has loDg been the internationally acclaimed expert on the Japanese film. He is a former member of Uni- Japan Film and film critic for The Japan Times, and is pres- ently Curator of the Film Department at the Museum of Modern Art, New York. He designed and presented the Kurosawa and Ozu retrospectives, as well as the massive 1970 retrospective at the museum, The Japanese Film. His book on The Films of Akira Kurosawa has been called a "virtual model for future studies in the field." Mr. Richie has been a resident of Japan for the past twenty-five years. Film books by Donald Richie: The Cinematographic View: A Study of the Film. 1958. The Japanese Film: Art and Industry. 1959. Co-authored with Joseph L. Anderson. Japanese Movies. 1961. The Japanese Movie: An Illustrated History. 1965. The Films of Akira Kurosawa. 1965. George Stevens: An American Romantic. 1970. Japanese Cine2wa Film Style and National Character Donald Ricliie Anchor Books DOUBLEDAY & COMPANY, INC., GABDKN CTTY, NEW YORK This book is an extensively revised, expanded, and updated version of Japanese Movies, © 1961 by Japan Travel Bureau. Original material reprinted by pemMSsion of the Japan Travel Bureau, Inc., Japan. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 77-163122 Copyright © 1971 by Donald Richie Copyright © 1961 by Japan Travel Bureau All Rights Reserved Printed in the United States of America CONTENTS List of Illiistrations vii Introduction xvii 1896-1945 1 194&-1971 59 Appendix 239 Index 250 LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS The Abe Clan, 1938. 29 An Actor's Revenge, 1963. -

Realist Cinema As World Cinema: Non- Cinema, Intermedial Passages, Total Cinema

Realist cinema as world cinema: non- cinema, intermedial passages, total cinema Book Published Version Creative Commons: Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 Open Access Nagib, L. (2020) Realist cinema as world cinema: non-cinema, intermedial passages, total cinema. Film Culture in Transition (670). Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam. ISBN 9789462987517 doi: https://doi.org/10.5117/9789462987517 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/87792/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5117/9789462987517 Publisher: Amsterdam University Press All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online FILM CULTURE IN TRANSITION Realist Cinema as World Cinema Non-cinema, Intermedial Passages, Total Cinema lúcia nagib Realist Cinema as World Cinema Realist Cinema as World Cinema Non-cinema, Intermedial Passages, Total Cinema Lúcia Nagib Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Photo by Mateo Contreras Gallego, for the film Birds of Passages (Pájaros de Verano, Cristina Gallego and Ciro Guerra, 2018), courtesy of the authors. Cover design: Kok Korpershoek Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6298 751 7 e-isbn 978 90 4853 921 5 doi 10.5117/9789462987517 nur 670 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) L. -

Ozu and World Cinema Daisuke Miyao Postdoctoral Fellow, Film

EAAS V3317: Ozu and World Cinema Daisuke Miyao Postdoctoral Fellow, Film Studies, University of California, Berkeley First offered as an ExEAS course at Columbia University in Fall 2003 Class Meetings: Monday & Wednesday 4:10-5:25 Screenings: Monday 6:10- 1. Course Description: Since the1960s, Japanese director Yasujiro Ozu (1903-1963) has been the object of increased popular and critical attention by international film scholars and audiences. Ozu is widely considered “the most Japanese” of Japanese directors, but what does “the most Japanese” mean? Do Ozu’s films express the special characteristics of Japanese cinema? If so, what constitutes the cultural specificity of Japanese cinema? At the same time, Ozu was a big fan of foreign films. The director considered “the most Japanese” was in fact steeped in foreign popular culture. How can Ozu be located in global film cultures and international histories of cinema? This course reexamines Ozu’s works in terms of their social and cultural context, from both national and transnational perspectives. It locates Ozu’s films at a dialogic focal point of Japanese, American and European cinema. Through an intense examination of Ozu’s films as primary texts, this course pays particular attention to Japanese modernization in the 1920s; the influence of wartime film policy; reconfiguration of traditional Japanese art forms during the postwar Occupation; the decline of the Japanese film studio system and the popularization of international film festivals. We will also discuss the mutual influence between American and European cinema and Ozu’s films and Ozu’s legacy in international films, including New German Cinema (Wim Wenders), American independent films (Jim Jarmusch), and contemporary Japanese films (Kiju Yoshida, Masayuki Suo). -

BANSHUN/LATE SPRING (1949, 108 Min) Directed by Yasujirô Ozu

September 27, 2016 (XXXIII:5) Yasujirö Ozu,: BANSHUN/LATE SPRING (1949, 108 min) Directed by Yasujirô Ozu Written by Kazuo Hirotsu (based on the novel "Chichi to musume" by), Kôgo Noda (screenplay) and Yasujirô Ozu (screenplay) Produced by Takeshi Yamamoto Music Senji Itô Cinematography Yûharu Atsuta Film Editing Yoshiyasu Hamamura Art Direction Tatsuo Hamada Set Decoration Mototsugu Komaki Costume Design Bunjiro Suzuki Makeup Department Toku Sakuma (key hair stylist), Hisae Kakizawa (hair stylist), Kingorô Yoshizawa ... hair stylist Production Management Dai Watanabe Mainichi Film Concours, 1950. Won : Best Film, Yasujirô Ozu (b. December 12, 1903 in Tokyo, Japan— Yasujirô Ozu; Best Actress: Setsuko Hara for Aoi d. December 12, 1963, age 60, in Tokyo, Japan) was a sanmyaku and Ojôsan kanpai; Best Director: Yasujirô movie buff from childhood, often playing hooky from Ozu; Best Screenplay: Yasujirô Ozu and Kôgo Noda school in order to see Hollywood movies in his local theatre. In 1923 he landed a job as a camera assistant at Cast Shochiku Studios in Tokyo. Three years later, he was Chishû Ryû…Shukichi Somiya made an assistant director and directed his first film the Setsuko Hara…Noriko Somiya next year, Blade of Penitence (1927). Ozu made thirty-five Yumeji Tsukioka…Aya Kitagawa silent films, and a trilogy of youth comedies with serious Haruko Sugimura…Masa Taguchi overtones he turned out in the late 1920s and early 1930s Hôhi Aoki…Katsuyoshi placed him in the front ranks of Japanese directors. He Jun Usami…Shôichi Hattori made his first sound film in 1936, The Only Son (1936), Kuniko Miyake…Akiko Miwa but was drafted into the Japanese Army the next year, Masao Mishima…Jo Onodera being posted to China for two years and then to Singapore Yoshiko Tsubouchi…Kiku when World War II started. -

(A) Cinema 41 the State of Things

FILM CULTURE IN TRANSITION Realist Cinema as World Cinema Non-cinema, Intermedial Passages, Total Cinema lúcia nagib Realist Cinema as World Cinema Realist Cinema as World Cinema Non-cinema, Intermedial Passages, Total Cinema Lúcia Nagib Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Photo by Mateo Contreras Gallego, for the film Birds of Passages (Pájaros de Verano, Cristina Gallego and Ciro Guerra, 2018), courtesy of the authors. Cover design: Kok Korpershoek Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout isbn 978 94 6298 751 7 e-isbn 978 90 4853 921 5 doi 10.5117/9789462987517 nur 670 Creative Commons License CC BY NC ND (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0) L. Nagib / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2020 Some rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, any part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise). Every effort has been made to obtain permission to use all copyrighted illustrations reproduced in this book. Nonetheless, whosoever believes to have rights to this material is advised to contact the publisher. Table of Contents List of Illustrations 7 Acknowledgements 11 Introduction 15 Part I Non-cinema 1 The Death of (a) Cinema 41 The State of Things 2 Jafar Panahi’s Forbidden Tetralogy 63 This Is Not a Film, Closed Curtain, Taxi Tehran, Three Faces 3 Film as Death 87 The Act of Killing 4 The Blind Spot of History 107 Colonialism in Tabu Part II -

Cteq-2019-Calendar.Pdf

FEBRUARY 6 FEBRUARY 13–27 MELBOURNE CINÉMATHÈQUE 2019 SCREENINGS OPENING NIGHT FIGURATIVE LANDSCAPES AND SOCRATIC CONVERSATIONS: FROM 6 FEBRUARY TO 22 MAY: THE VISIONARY CINEMA OF NURI BILGE CEYLAN WEDNESDAYS FROM 7PM AT ACMI, FEDERATION SQUARE, MELBOURNE. FROM 29 MAY TO 18 DECEMBER: WEDNESDAYS FROM 6:30PM (CHECK FOR EXCEPTIONS) AT RMIT CAPITOL THEATRE, 113 SWANSTON STREET, MELBOURNE. Presented by the Melbourne Cinémathèque and The Australian Centre WEDNESDAY 6 FEBRUARY WEDNESDAY 13 FEBRUARY WEDNESDAY 20 FEBRUARY WEDNESDAY 27 FEBRUARY for the Moving Image. The opening night of our 2019 program 7:00pm Nuri Bilge Ceylan (1959–) is one of 7:00pm 7:00pm 7:00pm Curated by the Melbourne Cinémathèque. features a recent restoration of one of ONCE UPON A TIME IN AMERICA the most critically lauded directors in ONCE UPON A TIME IN ANATOLIA THREE MONKEYS WINTER SLEEP the great “last works” of any director (EXTENDED VERSION) contemporary cinema and it’s easy to Nuri Bilge Ceylan (2011) 157 mins – M Nuri Bilge Ceylan (2008) 109 mins – M Nuri Bilge Ceylan (2014) 194 mins – M Supported by Film Victoria, the City of Melbourne Arts Grants Program and in the history of cinema, Sergio Sergio Leone (1984) 251 mins see why: his style frequently and openly the School of Media and Communication, RMIT University. Leone’s (1929–1989) truly monumental, Unclassified 18+ † evokes the sensibilities of some of the With this expressively forensic and A businessman accidentally kills a Ceylan’s exquisite but divisive Palme d’Or deeply cinephilic and profoundly cinema’s most highly revered auteurs beautifully detailed police procedural, pedestrian when driving late at night and winner is a “huge, sombre and compelling ANNUAL MEMBERSHIP knowing final film, Once Upon a Time A crime saga truly unparalleled in like Ingmar Bergman, Michelangelo Ceylan fully emerged as one of the great bargains with his chauffeur to take the tragicomedy” (Peter Bradshaw) set Admission for 12 months from date of purchase: in America.