1 How to Read the Good Manners of Yasujiro

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Port of Flowers Hanasaku Minato

Retrospectiva de Keisuke Kinoshita Port of Flowers Hanasaku minato B&W / Standard / 1943 / 82 min / Shochiku Cast: Director: Kinoshita Keisuke Shuzo: Ozawa Eitaro Script: Tsuji Yoshihiro Tomekichi: Uehara Ken Based on a play by: Kikuta Kazuo Okano: HiGashiyama Chieko CinematoGraphy: Kusuda Hiroshi Nobatama: Ryu Chishu Art Director: Motoki Isamu Hayashida: Tono Eijiro Music: Abe Sakari Okuda, villaGe chief: Sakamoto Takeshi Ryoji, his assistant: Hanzawa Yosuke Producer: Endo ShinGo Oharu, Ryoji’s sister: Mito Mitsuko Setsuyo: Maki Fusako Yuki: Murase Sachiko SettinG: A small island in Kyushu in 1941 Synopsis: A patriotic comedy about two con men arrivinG suddenly to work a scam on the inhabitants of a small Japanese island just as the nation beGins its entrance into World War II. The men claim to be the orphan sons of Watase Kenzo, who had come to the island and initiated a project to construct a shipyard 15 years prior. He left with the project half-completed but is remembered with Great fondness by the mayor and the Group of people who hold the most influence on the island, includinG Nobatama who runs the horse and carriaGe shop; Hayashida, the boss of the fishermen; and Okano, the owner of the inn. Okano had once chased Watase all the way to PenanG, still to find her love unrequited. Because of this history, she takes care of the two con men she has just met as if they were her own sons. The more experienced of the two, Shuzo, takes the name Kensuke (Watase), GivinG his partner Tomekichi the name Kenji. They announce their desire to revive the shipyard project, a proposal met with enthusiastic support from all but Hayashida, who is forever concerned with money. -

“We'll Embrace One Another and Go On, All Right?” Everyday Life in Ozu

“We’ll embrace one another and go on, all right?” Everyday life in Ozu Yasujirô’s post-war films 1947-1949. University of Turku Faculty of Humanities Cultural History Master’s thesis Topi E. Timonen 17.5.2019 The originality of this thesis has been checked in accordance with the University of Turku quality assurance system using the Turnitin OriginalityCheck service. UNIVERSITY OF TURKU School of History, Culture and Arts Studies Faculty of Humanities TIMONEN, TOPI E.: “We’ll embrace one another and go on, all right?” Everyday life in Ozu Yasujirô’s post-war films 1947-1949. Master’s thesis, 84 pages. Appendix, 2 pages. Cultural history May 2019 Summary The subject of my master’s thesis is the depiction of everyday life in the post-war films of Japanese filmmaker Ozu Yasujirô (1903-1963). My primary sources are his three first post- war films: Record of a Tenement Gentleman (Nagaya shinshiroku, 1947), A Hen in the Wind (Kaze no naka no mendori, 1948) and Late Spring (Banshun, 1949). Ozu’s aim in his filmmaking was to depict the Japanese people, their society and their lives in a realistic fashion. My thesis offers a close reading of these films that focuses on the themes that are central in their everyday depiction. These themes include gender roles, poverty, children, nostalgia for the pre-war years, marital equality and the concept of arranged marriage, parenthood, and cultural juxtaposition between Japanese and American influences. The films were made under American censorship and I reflect upon this context while examining the presentation of the themes. -

Cinefiles Document #37926

Document Citation Title Yasujiro Ozu: filmmaker for all seasons Author(s) Source Pacific Film Archive Date 2003 Nov 23 Type program note Language English Pagination No. of Pages 10 Subjects Ozu, Yasujiro (1903-1963), Tokyo, Japan Film Subjects Hitori musuko (The only son), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1936 Shukujo wa nani o wasureta ka (What did the lady forget?), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1937 Todake no kyodai (The brothers and sisters of the Toda family), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1941 Chichi ariki (There was a father), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1942 Nagaya shinshiroku (The record of a tenement gentleman), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1947 Ohayo (Good morning), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1959 Tokyo no yado (An inn at Tokyo), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1935 Hogaraka ni ayume (Walk cheerfully), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1930 Tokyo monogatari (Tokyo story), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1953 WARNING: This material may be protected by copyright law (Title 17 U.S. Code) Dekigokoro (Passing fancy), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1933 Shukujo to hige (The lady and the beard), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1931 Wakaki hi (Days of youth), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1929 Sono yo no tsuma (That night's wife), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1930 Kohayagawa-ke no aki (The end of summer), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1961 Rakudai wa shita keredo (I flunked, but...), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1930 Tokyo no gassho (Tokyo chorus), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1931 Banshun (Late spring), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1949 Seishun no yume ima izuko (Where now are the dreams of youth?), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1932 Munekata shimai (The Munekata sisters), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1950 Hijosen no onna (Dragnet girl), Ozu, Yasujiro, 1933 Ochazuke no aji (The flavor of green tea over rice), Ozu, -

Programmation Septembre 2020

Une sélection du meilleur du cinéma de patrimoine par Carlotta Films ! PROGRAMMATION SEPTEMBRE 2020 MIKIO NARUSE RÉALISATEUR DU MOIS 4 fi lms majeurs AU GRÉ DU COURANT (1956) QUAND UNE FEMME MONTE L’ESCALIER (1960) UNE FEMME DANS LA TOURMENTE (1964) NUAGES ÉPARS (1967) UNE FAMILLE DÉVOYÉE ÉVÉNEMENT SPÉCIAL : AVANT-PREMIÈRE EXCEPTIONNELLE un fi lm de Masayuki Suo (1984) - EXCLUSIVITÉ LE VIDÉO CLUB CARLOTTA FILMS (Int. -16 ans) - THE ENDLESS SUMMER DÉJÀ CULTE un fi lm de Bruce Brown (1966) THE EXTERMINATOR (LE DROIT DE TUER) DÉJÀ CULTE un fi lm de James Glickenhaus (1980) A FULLER LIFE DÉCOUVERTES & RARETÉS un fi lm de Samantha Fuller (2013) LE COUSIN JULES DÉCOUVERTES & RARETÉS un fi lm de Dominique Benicheti (1973) LE MONDE SUR LE FIL LE FILM FLEUVE un fi lm de Rainer Werner Fassbinder (1973) LEVIDEOCLUB.CARLOTTAFILMS.COM CARLOTTA FILMS 5-7, imp. Carrière-Mainguet 75011 Paris Tél. : 01 42 24 10 86 LE RÉALISATEUR DU MOIS MIKIO NARUSE DÉCOUVREZ 4 MAGNIFIQUES PORTRAITS DE FEMME PAR L’UN DES PLUS GRANDS CINÉASTES JAPONAIS AU GRÉ DU COURANT QUAND UNE FEMME MONTE L’ESCALIER UNE FEMME DANS LA TOURMENTE NUAGES ÉPARS Longtemps méconnue en Occident, l’œuvre de Mikio Naruse est aujourd’hui élevée au même rang que celle de ses compatriotes Mizoguchi, Ozu et Kurosawa. À partir des années 1950, il se spécialise dans le shomin geki, genre qui vise à dépeindre le quotidien des gens de la classe moyenne. Son œuvre à la fois poétique et réaliste, pleinement ancrée dans son temps, donne à voir de magnifiques portraits de femmes, portés par les plus grandes actrices du cinéma nippon comme Hideko Takamine, sa muse, ou Yoko Tsukasa. -

1. Title: 13 Tzameti ISBN: 5060018488721 Sebastian, A

1. Title: 13 Tzameti ISBN: 5060018488721 Sebastian, a young man, has decided to follow instructions intended for someone else, without knowing where they will take him. Something else he does not know is that Gerard Dorez, a cop on a knife-edge, is tailing him. When he reaches his destination, Sebastian falls into a degenerate, clandestine world of mental chaos behind closed doors in which men gamble on the lives of others men. 2. Title: 12 Angry Men ISBN: 5050070005172 Adapted from Reginald Rose's television play, this film marked the directorial debut of Sidney Lumet. At the end of a murder trial in New York City, the 12 jurors retire to consider their verdict. The man in the dock is a young Puerto Rican accused of killing his father, and eleven of the jurors do not hesitate in finding him guilty. However, one of the jurors (Henry Fonda), reluctant to send the youngster to his death without any debate, returns a vote of not guilty. From this single event, the jurors begin to re-evaluate the case, as they look at the murder - and themselves - in a fresh light. 3. Title: 12:08 East of Bucharest ISBN: n/a 12:08pm on the 22 December 1989 was the exact time of Ceausescu's fall from power in Romania. Sixteen years on, a provincial TV talk show decides to commemorate the event by asking local heroes to reminisce about their own contributions to the revolution. But securing suitable guests proves an unexpected challenge and the producer is left with two less than ideal participants - a drink addled history teacher and a retired and lonely sometime-Santa Claus grateful for the company. -

EL INTENDENTE SANSHO (V.O.S.) Martes, 5 De Junio, 18:00 Horas

ELEGÍA DE NANIWA (v.o.s) Martes, 17 de abril, 18:00 horas SINOPSIS FICHA TÉCNICA Ayako es una joven operadora telefónica Titulo Naniwa erejî prometida a su compañero Susumu, quien Genero Drama observa impasible el acoso que sufre la joven por Nacionalidad Japón parte de su jefe Asai. Tras enfrentarse a su padre Idioma original Japonés por una deuda que podría hundir a la familia, Duración 69 minutos Ayako se encuentra en la calle sin saber dónde Año de producción 1936 acudir. Llevada por la desesperación, la joven Dirección Kenji Mizoguchi acepta ser acogida por Asai como amante, Productor Masaichi Nagata enfrentándose a la humillación y el rechazo de su Guión Kenji Mizoguchi familia... Tadashi Fujiwara Yoshikata Yoda Basado en el relato “Mieko” de Saburo Okada Música Kôichi Takagi Fotografía bl. y n. Minoru Miki FICHA ARTíSTICA Ayako Murai Isuzu Yamada Susumu Nishimura Kensaku Hara Sonosuke Asai Benkei Shiganoya Junzo Murai Seiichi Takegawa Sachiko Murai Chiyoko Okura Hiroshi Murai Shinpachiro Asaka Sumiko Asai Yôko Umemura CRÍTICA “El primer filme sonoro del imprescindible Kenji Mizoguchi anuncia su madurez como cineasta, ya que tras 54 títulos mudos de temática melodramática y folletinesca éste decantó su obra hacia el realismo y la denuncia social. Elegía de Naniwa, que junto a Las hermanas Gion conforman un osado díptico que se acerca desde una óptica netamente feminista a la situación de la mujer en la patriarcal sociedad japonesa, narra el drama personal de Ayako, una joven telefonista que para sufragar las deudas contraídas por su padre se ve obligada a convertirse en la querida de un acaudalado empresario. -

March 10—April 27, 2006 in THIS ISSUE WELCOME to Contents the SILVER! in Less Than Three Years, AFI Silver Theatre 2

AMERICAN FILM INSITUTE GUIDE TO THEATRE AND MEMBER EVENTS March 10—April 27, 2006 IN THIS ISSUE WELCOME TO Contents THE SILVER! In less than three years, AFI Silver Theatre 2. LETTER FROM THE DIRECTOR has established itself as one of Washington’s premier cultural destinations, with BILLY WILDER AT 100 3. exceptional movies, premieres 3. SPECIAL EVENT: SOME LIKE IT HOT, WITH and star-studded events. To AFI FOUNDING DIRECTOR GEORGE STEVENS, JR. spread the word, we’re delight- ed to offer our AFI PREVIEW film 6. JAPANESE MASTER MIKIO NARUSE: “A CALM SURFACE programming guide to AFI Silver AND A RAGING CURRENT” Members and more than 100,000 households in the area through The 9. CINEMA TROPICAL: 25 WATTS, DIAS DE SANTIAGO Gazette. To those of you new to AFI Silver, welcome. And to our more AND EL CARRO than 5,000 loyal members, thank you for your continued support. With digital video projection and Lucasfilm THX certification in all 10. THE WORLD OF TERRENCE MALICK three of its gorgeous theaters, AFI Silver also offers the most advanced and most comfortable movie-going experience available anywhere. If SAVE THE DATE! SILVERDOCS: “THE PRE-EMINENT 11. you haven’t visited yet, there’s a treat waiting for you. From the earliest US DOCUMENTARY FEST” silent movies to 70mm epics to the latest digital technologies, AFI Silver 12. MEMBERSHIP NEWS connects you to the best the art form has to offer. Just leaf through these pages and see what is in store for you. This 13. SPECIAL ENGAGEMENTS: LIMITED RUNS! past year, in addition to such first-run sensations as CRASH, HOTEL BLACK ORPHEUS, THE RIVER AND MOUCHETTE RWANDA, MARCH OF THE PENGUINS and GOOD NIGHT, AND 14. -

4 Pages Cycle Japon 2.Indd

Ciné-mémoire Japon EEldoradoldorado SSaintaint PierrePierre En Juillet & Août 2018 Faire un cycle ciné-mémoire sur le Japon, c’est obligatoirement sélectionner et faire des choix difficiles tant la cinématographie japonaise est pourvue en chef-d’oeuvre du 7e art. Notre sélection s’est portée sur quelques grands maîtres des différentes périodes : - Pour les années 30/50 : Yasujiro Ozu et Akira Kurosawa CINE CONCERT Les années 60 : Mikio Naruse et Seijun Susiki Les années 70 : Nagisa Oshima Les années 80 : Shôhei Immara Les années 90 : Takeshi Kitano et Hayao Miyazaki ciné - concert Mer 8 août 21h accompagné en direct par le pianiste Christofer Bjurström avec le film muet Gosses de Tokyo d’ Yasujiro Ozu. Nous ferons une incursion dans le cinéma japonais contemporain lors d’une journée exceptionnelle 15h 18h 21h du 12 au 15 juillet les 18,19, & 22 juillet les 28, 27, & 29 juillet RAN UNE FEMME DANS LA LA BALLADE DE Drame - 1985- 2h45 TOURMENTE de Akira Kurosawa NARAYAMA Drame - 1964 - 1h38 Drame - 1983 - 2h10 avec Tatsuya Nakadai, Akira Terao, Jinpachi de Mikio Naruse de Shôhei Imamura Nezu avec Kumeko Urabe, Yûzô Kayama, Hideko avec Ken Ogata, Sumiko Sakamoto, Aki Takejo Takamine, Aiko Mimasu, MitsukoKusabue Palme d’or au festival de Cannes 1983 Dans le Japon du XVIe siècle, le seigneur Hidetora Ichimonji décide de se retirer et de partager son domaine entre ses trois fi ls, Taro, Jiro et Saburo. Mais la répartition de cet héritage va déchirer la famille. Orin, une vieille femme des montagnes du Reiko, veuve de guerre qui s’occupe du petit Shinshu, atteint l’âge fatidique de soixante- Akira Kurosawa était fasciné par l’histoire de commerce de ses beaux-parents, voit son dix ans. -

Cinema Year Book of Japan 1938

.1 Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2017 with funding from Media History Digital Library https://archive.org/details/cinemayearbookof00inte_0 CINEMA YEAR BOOK OF JAPAN 1938 EDITED BY THE INTERNATIONAL CINEMA ASSOCIATION OF JAPAN PUBLISHED BY KQKUSAI BUNKA SHINKOKAI The Society for International Cultural Relations TOKYO, JAPAN PRINTED IN JAPAN, 1938 PREFACE The vigorous culture of Japan is rooted in the traditions of more than twenty-five centuries. Through many years Japan has been looked upon with admiration as a land of dreams and imagination by only a limited number of interested people. Still less is the number of those who know the real Japan in which old tradition is harmoniously blended with the civilization of the new age. Herein lies the necessity to introduce to the world the true features of present-day Japan. The cultural activities of our country have witnessed a remarkable advance in recent years in civilization, whether liberal arts or arts. Cinematography too, has kept every field of spiritual fine , abreast with this general cultural advancement. The motion-picture industry of our country which, only a few years ago, met barely ivith the needs within the country, has begun to send forth its pro- ductions to the international market, the realization of an ideal cherished for many years. The Japanese film production to-day is steadily equipping itself ivith the ultimate aim of participating in the stage of international cinema activities. As already mentioned in the Cinema Year Book of last year, it will not be long before the Japanese films will play a significant role in the world market. -

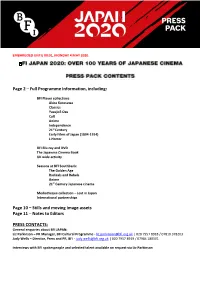

Notes to Editors PRESS

EMBARGOED UNTIL 00:01, MONDAY 4 MAY 2020. Page 2 – Full Programme Information, including: BFI Player collections Akira Kurosawa Classics Yasujirō Ozu Cult Anime Independence 21st Century Early Films of Japan (1894-1914) J-Horror BFI Blu-ray and DVD The Japanese Cinema Book UK wide activity Seasons at BFI Southbank: The Golden Age Radicals and Rebels Anime 21st Century Japanese cinema Mediatheque collection – Lost in Japan International partnerships Page 10 – Stills and moving image assets Page 11 – Notes to Editors PRESS CONTACTS: General enquiries about BFI JAPAN: Liz Parkinson – PR Manager, BFI Cultural Programme - [email protected] | 020 7957 8918 / 07810 378203 Judy Wells – Director, Press and PR, BFI - [email protected] | 020 7957 8919 / 07984 180501 Interviews with BFI spokespeople and selected talent available on request via Liz Parkinson FULL PROGRAMME HIGHLIGHTS EMBARGOED UNTIL 00:01, MONDAY 4 MAY 2020. BFI PLAYER COLLECTIONS The BFI’s VOD service BFI Player will be the premier destination for Japanese film this year with thematic collections launching over a six month period (May – October): Akira Kurosawa (11 May), Classics (11 May), Yasujirō Ozu (5 June), Cult (3 July), Anime (31 July), Independence (21 August), 21st Century (18 September) and J-Horror (30 October). All the collections will be available to BFI Player subscribers (£4.99 a month), with a 14 day free trial available to new customers. There will also be a major new free collection Early Films of Japan (1894-1914), released on BFI Player on 12 October, featuring material from the BFI National Archive’s significant collection of early films of Japan dating back to 1894. -

小津安二郎ありき Ozu Yasujirō Retrospective at Yale University

小津安二郎ありき Ozu Yasujirō Retrospective at Yale University September 19 – November 13, 2008 Presented by the Council on East Asian Studies at Yale University and the Cinema at the Whitney We are very pleased to be able to present thirteen films by one of the world’s most renowned film directors, Ozu Yasujirō. Among the trio of great Japanese cinema masters, Ozu, Kurosawa Akira, and Mizoguchi Kenji, Ozu was the last to be introduced abroad (largely after his death in 1963), yet is now arguably the most celebrated. His Tokyo Story was selected as the fifth best film of all time in Sight and Sound’s illustrious poll of world critics in 2002, and a legion of directors, from Wim Wenders to Hou Hsiao-hsien, have professed their admiration and influence. With the celebration of the centenary of his birth in 2003, there are still studies on Ozu coming out, including a translation or the director Yoshida Yoshishige’s marvelous Ozu’s Anti-Cinema (Ann Arbor: Center for Japanese Studies, University of Michigan, 2003), in which the New Wave director who once criticized his studio elder, re-appraises him forty years later. There is a veritable cottage industry of books on him in Japan. Why does Ozu still fascinate us after so many years? In some ways, it is because his films are so versatile and can speak to multiple perspectives and multiple generations. To some, he is the most Japanese of directors, depicting the sweet pathos of family life through a still camera that remains close to the floor, like a Japanese guest sitting on a tatami mat. -

Mid-August Lunch

Tokyo story Director: Yasujiro Ozu Country: Japan Date: 1953 An article by Eric Snider for film.com: Of Tokyo Story, Roger Ebert wrote: “It ennobles the cinema. It says, yes, a movie can help us make small steps against our imperfections.” Jeffrey Overstreet observed: “These characters never surprise us with anything showy, lurid, or sensational. They’re ordinary human beings, treated with fierce attention that feels like deep respect.” Philip French called it “one of the cinema’s most profound and moving studies of married love, aging and the relations between parents and children.” This is high praise for a Japanese film that the average moviegoer may not have heard of, by a director who isn’t a household name. Why does Tokyo Story win such accolades in movie-buff circles? Let’s take off our shoes by the door and investigate. The praise: Every 10 years, the British Film Institute’s Sight & Sound magazine surveys a large, international group of critics and film experts to compile a list of the greatest films of all time. Tokyo Story appeared on the two most recent lists, at No. 3 in 1992 and No. 5 in 2002. [It also ranked No.3 in 2012.] The movie is also included on Time magazine and Empire magazine’s lists of the best films of the 20th century. The context: Now considered one of Japan’s greatest directors, Yasujiro Ozu (1903-1963) wasn’t well- known outside his homeland until after his death. His most acclaimed film, Tokyo Story, was made in 1953 but didn’t play in the U.S.