2009 MMUF Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellowship Journal 2018

The Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellowship Journal 2018 Through subtle shades of color, the cover design represents the layers of richness and diversity that flourish within minority communities. The Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellowship Journal 2018 A collection of scholarly research by fellows of the Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellowship Program Preface We are proud to present to you the 2018 edition of the Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellowship Journal. For more than 30 years, the Mellon Mays Undergraduate Fellowship (MMUF) program has endeavored to promote diversity in the faculty of higher education, specifically by supporting thousands of students from underrepresented minority groups in their goal of obtaining PhDs. With the MMUF Journal, we provide an additional opportunity for students to experience academia through exposure to the publishing process. In addition to providing an audience for student work, the journal offers an introduction to the publishing process, including peer review and editor-guided revision of scholarly work. For the majority of students, the MMUF Journal is their first experience in publishing a scholarly article. The 2018 Journal features writing by 27 authors from 22 colleges and universities that are part of the program’s member institutions. The scholarship represented in the journal ranges from research conducted under the MMUF program, introductions to senior theses, and papers written for university courses. The work presented here includes scholarship from a wide range of disciples, from history to linguistics to political science. The papers presented here will take the reader on a journey. Readers will travel across the U.S., from Texas to South Carolina to California, and to countries ranging from Brazil and Nicaragua to Germany and South Korea, as they learn about theater, race relations, and the refugee experience. -

Women, Business and the Law 2020 World Bank Group

WOMEN, BUSINESS AND THE LAW 2020 AND THE LAW BUSINESS WOMEN, WOMEN, BUSINESS AND THE LAW 2020 WORLD BANK GROUP WORLD WOMEN, BUSINESS AND THE LAW 2020 © 2020 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org Some rights reserved 1 2 3 4 23 22 21 20 This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the govern- ments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Nothing herein shall constitute or be considered to be a limitation upon or waiver of the privileges and immunities of The World Bank, all of which are specifically reserved. Rights and Permissions This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/3.0/igo. Under the Creative Commons Attribution license, you are free to copy, distribute, transmit, and adapt this work, including for commercial purposes, under the following conditions: Attribution—Please cite the work as follows: World Bank. 2020. Women, Business and the Law 2020. -

Science Chunks: Plants Sample Packet Teach Your Students the Basics About Plants in Bite-Sized Chunks

Science Chunks: Plants Sample Packet Teach your students the basics about plants in bite-sized chunks. The following sample packet includes most of the first lesson of the Science Chunks: Plants digital unit study. You will see: 9 The Introduction (beginning on p. 4) 9 The Lesson (beginning on p. 8) 9 The Lapbooking Templates (beginning on p. 11) 9 The Notebooking Templates (beginning on p. 14) If you have questions about what you see, please let us know by emailing support@ elementalscience.com. To get started, head to: https://elementalscience.com/products/science-chunks-plants-unit A Peek Inside a Science Chunks Unit 5 1. Lesson Topic 1 Focus on one main idea throughout the week. You will learn about these ideas by reading from visually appealing encyclopedias, recording what 2 the students learned, and doing coordinating hands-on science activities. 2. Information Assignments Find two reading options—one for younger 3 students, one for older students, plus optional library books. 3. Notebooking Assignments Record what your students have learned with either a lapbook or a notebook. The directions for these options are included for 4 your convenience in this section along with the vocabulary the lesson will cover. 4. Hands-on Science Assignments Get the directions for coordinating hands-on science activities that relate to the week’s topic. 5 5. Lesson To-Do Lists See what is essential for you to do each week and what is optional. You can check these off as you work through the lesson so that you will know when you are ready to move on to the next 6 one. -

Youth and Child Advocate and Educator Manual of Activities and Exercises for Children and Youth

Youth and Child Advocate and Educator Manual of Activities and Exercises for Children and Youth Compiled by Youth and Child Advocates and Youth Educators of the Vermont Network Against Domestic and Sexual Violence October 2009 Revised January 2011 PO Box 405, Montpelier, VT 05601 (802) 223-1302/ www.vtnetwork.org Youth and Child Advocate and Educator Manual of Activities and Exercises for Children and Youth Compiled by Youth and Child Advocates and Youth Educators of the Vermont Network Against Domestic and Sexual Violence October 2009 Revised January 2011 For use at Network Programs Credit is noted where activities were adapted or derived from other sources We have made every best effort to cite the origins of the activities contained in this manual. Some activities have been handed down through generations of Advocates without documentation and their origins are unknown to us. Our intention is to give credit where credit is due and we respectfully request any recognized or updated information be forwarded to the Vermont Network Against Domestic and Sexual Violence for citation purposes. PO Box 405, Montpelier, VT 05601 (802) 223-1302/ www.vtnetwork.org This project was supported by grant no. 2004-WR-AX-0030 awarded by the Violence Against Women Office, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. Points of view in this document are those of author and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. Table of Contents Body Image ............................................................................................................................................................... 5 1. Good Body (Circle), Middle and High School .................................................................................................. 6 2. What My Body Does for Me (The Advocacy Program at Umbrella) K-12; Adults .......................................... -

Catalogue 229 Japanese and Chinese Books, Manuscripts, and Scrolls Jonathan A. Hill, Bookseller New York City

JonathanCatalogue 229 A. Hill, Bookseller JapaneseJAPANESE & AND Chinese CHINESE Books, BOOKS, Manuscripts,MANUSCRIPTS, and AND ScrollsSCROLLS Jonathan A. Hill, Bookseller Catalogue 229 item 29 Catalogue 229 Japanese and Chinese Books, Manuscripts, and Scrolls Jonathan A. Hill, Bookseller New York City · 2019 JONATHAN A. HILL, BOOKSELLER 325 West End Avenue, Apt. 10 b New York, New York 10023-8143 telephone: 646-827-0724 home page: www.jonathanahill.com jonathan a. hill mobile: 917-294-2678 e-mail: [email protected] megumi k. hill mobile: 917-860-4862 e-mail: [email protected] yoshi hill mobile: 646-420-4652 e-mail: [email protected] member: International League of Antiquarian Booksellers, Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association of America & Verband Deutscher Antiquare terms are as usual: Any book returnable within five days of receipt, payment due within thirty days of receipt. Persons ordering for the first time are requested to remit with order, or supply suitable trade references. Residents of New York State should include appropriate sales tax. printed in china item 24 item 1 The Hot Springs of Atami 1. ATAMI HOT SPRINGS. Manuscript on paper, manuscript labels on upper covers entitled “Atami Onsen zuko” [“The Hot Springs of Atami, explained with illustrations”]. Written by Tsuki Shirai. 17 painted scenes, using brush and colors, on 63 pages. 34; 25; 22 folding leaves. Three vols. 8vo (270 x 187 mm.), orig. wrappers, modern stitch- ing. [ Japan]: late Edo. $12,500.00 This handsomely illustrated manuscript, written by Tsuki Shirai, describes and illustrates the famous hot springs of Atami (“hot ocean”), which have been known and appreciated since the 8th century. -

® Wiseburn Administrators Earn Honors Seeking the Truth of Ancestry

FREE Education + Communication = A Better Nation ® Covering the Wiseburn School District VOLUME 5, IssUE 13 www.SchoolNewsRollCall.com MARCh–MAY 2013 SUPERINTENDENT Wiseburn Administrators Earn Honors Wiseburn By Chris Jones, Ed.D. Director of Curriculum, Unification and Instruction, and Technology Wiseburn High Dr. Tom Johnstone: Pepperdine School Project University Superintendent of the Year Closing in on Since 2008, Superintendent Dr. Tom Johnston Success has led the Wiseburn School District toward As we move new levels of success. His boundless energy and deeper into 2013, determination to create innovative programs Dr. Tom the Wiseburn School Johnstone designed to help all students succeed have resulted District continues to in his being designated as Superintendent of forge ahead on two very significant the Year for 2013 by Pepperdine University. This fronts: Wiseburn unification and the distinction caps off a year of unprecedented Wiseburn High School Project. milestones achieved by Wiseburn in student There is much excitement in academic performance, facilities upgrades, and the community as Wiseburn gets significant progress in the long-desired movement closer to establishing a beautiful towards a unified K–12 Wiseburn School District. high school facility that will be Before joining the Wiseburn School District, Dr. the centerpiece of the Wiseburn Johnstone was a familiar face around town, as two community in the decades that of his children attended Anza School, where his lie ahead. On January 11, 2013, wife Terry is a first-grade teacher. Dr. Johnstone the district started the 45-day had established his professional reputation in the public review period for the Draft area by faithfully serving students in the Lennox Environmental Impact Report School District for 28 years as a teacher, counselor, (DEIR) for Wiseburn High School. -

Diaspora Engagement on Country Entrepreneurship and Investment Poli Cy Trends and Notable Practices in the Rabat Process Region

Background Paper Diaspora Engagement on Country Entrepreneurship and Investment Poli cy Trends and Notable Practices in the Rabat Process region Authors Valérie Wolff, International Centre for Migration Policy Development ICMPD Stella Opoku-Owusu, African Foundation for Development, AFFORD Diasmer Bloe, African Foundation for Development, AFFORD Background paper coordinated by the Secretariat of the Rabat Process, ICMPD Background paper for the Rabat Process Thematic Meeting on Diaspora Engagement Strategies: Entrepreneurship and Investment, 5-6 October in Bamako, Mali Project financed by the European Union Project implemented by ICMPD In the framework of the project “Support to Africa-EU Migration and Mobility Dialogue (MMD)” Introduction Diaspora entrepreneurship and investments are often hailed as drivers of economic development and positive change, and there is enough evidence to support this: 80% of FDI in China is from the Chinese diaspora, Indian diasporas in the USA have played an instrumental role in building up India’s IT industry and creating a second ‘Silicon Valley’ in their country -- to name some of the well-known success stories. This is no different to African diaspora actors. So who are these people and how have they become so engaged with their home countries? Often classified as ‘diaspora entrepreneurs’, they represent the group of migrants or those of migrant origin who are entrepreneurs, live outside of their home country, yet stay involved.1 It implies a transnational element of entrepreneurship between one or more -

Terrorist and Organized Crime Groups in the Tri-Border Area (Tba) of South America

TERRORIST AND ORGANIZED CRIME GROUPS IN THE TRI-BORDER AREA (TBA) OF SOUTH AMERICA A Report Prepared by the Federal Research Division, Library of Congress under an Interagency Agreement with the Crime and Narcotics Center Director of Central Intelligence July 2003 (Revised December 2010) Author: Rex Hudson Project Manager: Glenn Curtis Federal Research Division Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 205404840 Tel: 2027073900 Fax: 2027073920 E-Mail: [email protected] Homepage: http://loc.gov/rr/frd/ p 55 Years of Service to the Federal Government p 1948 – 2003 Library of Congress – Federal Research Division Tri-Border Area (TBA) PREFACE This report assesses the activities of organized crime groups, terrorist groups, and narcotics traffickers in general in the Tri-Border Area (TBA) of Argentina, Brazil, and Paraguay, focusing mainly on the period since 1999. Some of the related topics discussed, such as governmental and police corruption and anti–money-laundering laws, may also apply in part to the three TBA countries in general in addition to the TBA. This is unavoidable because the TBA cannot be discussed entirely as an isolated entity. Based entirely on open sources, this assessment has made extensive use of books, journal articles, and other reports available in the Library of Congress collections. It is based in part on the author’s earlier research paper entitled “Narcotics-Funded Terrorist/Extremist Groups in Latin America” (May 2002). It has also made extensive use of sources available on the Internet, including Argentine, Brazilian, and Paraguayan newspaper articles. One of the most relevant Spanish-language sources used for this assessment was Mariano César Bartolomé’s paper entitled Amenazas a la seguridad de los estados: La triple frontera como ‘área gris’ en el cono sur americano [Threats to the Security of States: The Triborder as a ‘Grey Area’ in the Southern Cone of South America] (2001). -

The Story of the World Activity Book One Ancient Times from the Earliest Nomads to the Last Roman Emperor

The Story of the World Activity Book One Ancient Times From the Earliest Nomads to the Last Roman Emperor Edited by Susan Wise Bauer With activities, maps, and drawings by: Joyce Crandell, Sheila Graves, Terri Johnson, Lisa Logue, Karla Middleton, Tiffany Moore, Matthew and Katie Moore, Kimberly Shaw, Jeff West, and Sharon Wilson Peace Hill Press www.peacehillpress.com Table of Contents Table of Contents .....................................................................................................i Reprinting Notice ....................................................................................................v How to Use This Activity Book ...............................................................................vi Pronunciation Guide for Reading Aloud .................................................................ix Parent’s Guide (see “Chapters” list below for chapter-specific page numbers) ......................1 Each chapter contains: t&ODZDMPQFEJB$SPTT3FGFSFODFT t3FWJFX2VFTUJPOT t/BSSBUJPO&YFSDJTF t"EEJUJPOBM)JTUPSZ3FBEJOH t$PSSFTQPOEJOH-JUFSBUVSF4VHHFTUJPOT t$PMPSJOH1BHF t.BQ8PSL t"DUJWJUJFT Map Answer Key .................................................................................................167 Student Pages (indicated by “SP” preceding page number) ............................................SP 1 Chapters Introduction — How Do We Know What Happened? in The Story of the World text ......................................13 in The Story of the World text (revised) ......................... 1 Activity Book -

A •Œneo-Abolitionist Trendâ•Š in Sub-Saharan Africa? Regional Anti

Seattle Journal for Social Justice Volume 9 Issue 2 Spring/Summer 2011 Article 4 May 2011 A “Neo-Abolitionist Trend” in Sub-Saharan Africa? Regional Anti- Trafficking Patterns and a Preliminary Legislative Taxonomy Benjamin N. Lawrance Ruby P. Andrew Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/sjsj Recommended Citation Lawrance, Benjamin N. and Andrew, Ruby P. (2011) "A “Neo-Abolitionist Trend” in Sub-Saharan Africa? Regional Anti-Trafficking Patterns and a Preliminary Legislative Taxonomy," Seattle Journal for Social Justice: Vol. 9 : Iss. 2 , Article 4. Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/sjsj/vol9/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications and Programs at Seattle University School of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Seattle Journal for Social Justice by an authorized editor of Seattle University School of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 599 A “Neo-Abolitionist Trend” in Sub-Saharan Africa? Regional Anti-Trafficking Patterns and a Preliminary Legislative Taxonomy Benjamin N. Lawrance and Ruby P Andrew INTRODUCTION In the decade since the US Department of State (USDOS) instituted the production of its annual Trafficking in Persons (TIP) Report, anti- trafficking measures have been passed across the globe, and the US role in setting standards and paradigms for anti-trafficking has been extensively analyzed and criticized.1 Through its Office to Monitor and Combat Trafficking in Persons (OMCTP), the USDOS’ three-tier categorization of nations’ trafficking measures continues to play a pivotal role in shaming recalcitrant nations into responding to accusations of trafficking within and across their respective borders.2 No region has experienced so dramatic a transformation with respect to the USDOS agenda of “prevention, protection, and prosecution” than sub- Saharan Africa.3 No sub-Saharan African nation had an anti-trafficking statute at the start of the millennium. -

American Community Survey and Puerto Rico Community Survey

American Community Survey and Puerto Rico Community Survey 2016 Code List 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS ANCESTRY CODE LIST 3 FIELD OF DEGREE CODE LIST 25 GROUP QUARTERS CODE LIST 31 HISPANIC ORIGIN CODE LIST 32 INDUSTRY CODE LIST 35 LANGUAGE CODE LIST 44 OCCUPATION CODE LIST 80 PLACE OF BIRTH, MIGRATION, & PLACE OF WORK CODE LIST 95 RACE CODE LIST 105 2 Ancestry Code List ANCESTRY CODE WESTERN EUROPE (EXCEPT SPAIN) 001-099 . ALSATIAN 001 . ANDORRAN 002 . AUSTRIAN 003 . TIROL 004 . BASQUE 005 . FRENCH BASQUE 006 . SPANISH BASQUE 007 . BELGIAN 008 . FLEMISH 009 . WALLOON 010 . BRITISH 011 . BRITISH ISLES 012 . CHANNEL ISLANDER 013 . GIBRALTARIAN 014 . CORNISH 015 . CORSICAN 016 . CYPRIOT 017 . GREEK CYPRIOTE 018 . TURKISH CYPRIOTE 019 . DANISH 020 . DUTCH 021 . ENGLISH 022 . FAROE ISLANDER 023 . FINNISH 024 . KARELIAN 025 . FRENCH 026 . LORRAINIAN 027 . BRETON 028 . FRISIAN 029 . FRIULIAN 030 . LADIN 031 . GERMAN 032 . BAVARIAN 033 . BERLINER 034 3 ANCESTRY CODE WESTERN EUROPE (EXCEPT SPAIN) (continued) . HAMBURGER 035 . HANNOVER 036 . HESSIAN 037 . LUBECKER 038 . POMERANIAN 039 . PRUSSIAN 040 . SAXON 041 . SUDETENLANDER 042 . WESTPHALIAN 043 . EAST GERMAN 044 . WEST GERMAN 045 . GREEK 046 . CRETAN 047 . CYCLADIC ISLANDER 048 . ICELANDER 049 . IRISH 050 . ITALIAN 051 . TRIESTE 052 . ABRUZZI 053 . APULIAN 054 . BASILICATA 055 . CALABRIAN 056 . AMALFIAN 057 . EMILIA ROMAGNA 058 . ROMAN 059 . LIGURIAN 060 . LOMBARDIAN 061 . MARCHE 062 . MOLISE 063 . NEAPOLITAN 064 . PIEDMONTESE 065 . PUGLIA 066 . SARDINIAN 067 . SICILIAN 068 . TUSCAN 069 4 ANCESTRY CODE WESTERN EUROPE (EXCEPT SPAIN) (continued) . TRENTINO 070 . UMBRIAN 071 . VALLE DAOSTA 072 . VENETIAN 073 . SAN MARINO 074 . LAPP 075 . LIECHTENSTEINER 076 . LUXEMBURGER 077 . MALTESE 078 . MANX 079 . -

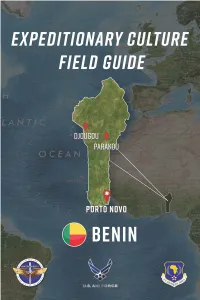

ECFG-Benin-Apr-19.Pdf

About this Guide This guide is designed to prepare you to deploy to culturally complex environments and achieve mission objectives. The fundamental information contained within will help you understand the decisive cultural dimension of your assigned location and gain skills necessary for success (Photo: Beninese medics perform routine physical examinations on local residents of Wanrarou, Benin). ECFG The guide consists of 2 parts: Part 1 introduces “Culture General,” the foundational knowledge you need to operate effectively in any global environment. Benin Part 2 presents “Culture Specific” Benin, focusing on unique cultural features of Beninese society and is designed to complement other pre-deployment training. It applies culture- general concepts to help increase your knowledge of your assigned deployment location (Photo: Beninese Army Soldier practices baton strikes during peacekeeping training with US Marine in Bembereke, Benin). For further information, visit the Air Force Culture and Language Center (AFCLC) website at www.airuniversity.af.edu/AFCLC/ or contact AFCLC’s Region Team at [email protected]. Disclaimer: All text is the property of the AFCLC and may not be modified by a change in title, content, or labeling. It may be reproduced in its current format with the expressed permission of the AFCLC. All photography is provided as a courtesy of the US government, Wikimedia, and other sources as indicated. GENERAL CULTURE PART 1 – CULTURE GENERAL What is Culture? Fundamental to all aspects of human existence, culture shapes the way humans view life and functions as a tool we use to adapt to our social and physical environments. A culture is the sum of all of the beliefs, values, behaviors, and symbols that have meaning for a society.