Does M&A Create Value in the Pharmaceutical Sector?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Lipid Association Annual Summary of Clinical Lipidology 2016 Disclosures Dr. Harold E. Bays: Dr. Bays Discloses That He

National Lipid Association Annual Summary of Clinical Lipidology 2016 Disclosures Dr. Harold E. Bays: Dr. Bays discloses that he has received research grants from Arena Pharmaceuticals, Boehringer Ingelheim, Cargill Inc., GlaxoSmithKline, Novo Nordisk, Orexigen Therapeutics, Shionogi, Takeda, Stratum Nutrition, California Raisin Board, Esperion, Essentialis, Forest, Gilead Sciences Inc., Given, Hoffman-LaRoche, Home Access, Novartis, Omthera, Pfizer, Trygg Pharmaceuticals, TWI Bio, Xoma, Ardea Inc., High Point Pharmaceuticals LLC, Micropharma Limited, TransTech Pharma Inc., TIMI, Pozen, Regeneron, and Elcelyx. He further discloses that he has received honoraria/research grants from Amarin, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Catabasis, Daiichi-Sankyo Inc., Eisai, Merck & Co, VIVUS, Zeomedex, and WPU. Dr. Peter H. Jones: Dr. Jones has received consulting or speaker honoraria from Merck and Co., Amgen, and Sanofi-Aventis/Regeneron. Dr. W. Virgil Brown: Dr. Brown is the editor of the Journal of Clinical Lipidology and further discloses that he has received consulting fees/honoraria from Akcea, Esperion, Regeneron, Amgen, Genzyme, Pfizer Inc., Merck and Co, GlaxoSmithKline, Medtelligence, and Vindico. Dr. Terry A. Jacobson: Dr. Jacobson has received consulting fees from Merck and Co., Amarin, Amgen, AstraZeneca, and Regeneron/Sanofi-Aventis. Dr. Karen E. Aspry: Dr. Aspry has no disclosures to report. Dr. Christie M. Ballantyne: Dr. Ballantyne has received research grants from Abbott Diagnostics, Amarin, Amgen, Eli Lilly, Esperion, ISIS Pharmaceuticals, Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Otsuka, Regeneron, Roche Diagnostic, Sanofi-Synthelabo, and Takeda Pharmaceuticals. He has also received consulting fees from Abbott Diagnostics, Amarin, Amgen, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Esperion, Genzyme, ISIS Pharmaceuticals, Matinas BioPharma Inc., Merck and Co., Novartis Pharmaceuticals, Pfizer, Regeneron, Roche, and Sanofi-Synthelabo. -

Executive Profile: Genzyme's CEO on Dark Times, Transition and the Long

June 15th 2015 scripintelligence.com Executive profile: Genzyme’s CEO on dark times, transition and the long view David Meeker, CEO of Sanofi company Genzyme, recently found himself hustling back to Genzyme’s Kendall Square offices from a nearby meeting to talk to Scrip’s editor Eleanor Malone about the challenges and opportunities he has encountered in his varied career. In the first of a two-part series, he discusses his experiences in the company that he joined in 1994, and expounds upon issues faced by the industry as a whole. Eleanor Malone: Genzyme went through some dark times before the Sanofi acquisition with the manufacturing issues that led to shortages of enzyme replacement therapies. What lessons did you draw from those difficulties? David Meeker: You are absolutely correct; they were incredibly painful, dark moments. We failed to deliver on the implicit promise David Meeker addresses employees at of ensuring that patients can access the Genzyme’s HQ following a torch relay connecting the company’s sites near Boston medicines that they need. I think we learned to mark International Rare Diseases Day many lessons. On a very tactical level we learned about the lead time that it takes to bring biologic manufacturing up – we realised it right for the patient, given the limitations Many acquisitions destroy value, and a lot too late that we were not going to be at an we had. We were short of product so we had of the destruction happens when people adequate capacity and by the time we started to focus on how to manage the distribution leave: you have the products but you lose to build, even though it was several years of that product in a way which was most the know-how and the critical talent that ahead of when we ran out of medicine, we equitable. -

Dyax Corp. 300 Technology Square Cambridge, MA 02139 617 225-2500

Dyax Corp. 300 Technology Square Cambridge, MA 02139 617 225-2500 www.dyax.com Other Offices Dyax SA, Liege, Belgium ADVANCING NOVEL THERAPEUTIC PRODUCTS Dyax Corp. Annual Report 2003 Corporate Information Dyax Achievements 2003 Dyax Goals 2004 Directors Executive Officers and Stock Listing Henry E. Blair Key Employees Common stock has been traded on the Nasdaq Stock Market Advances in Clinical Development Clinical Development Chairman, President and Henry E. Blair* under the symbol DYAX since our initial public offering in Milestones Chief Executive Officer, Chairman, President and August 14, 2000. DX-88/Hereditary Angioedema Dyax Corp. Chief Executive Officer DX-88/Hereditary Constantine E. Stephen S. Galliker, CPA* The following table gives the quarterly high and low sales G Completed 9-patient Phase II trial, met primary endpoints Angioedema Anagnostopoulos, Ph.D. EVP Finance and prices of our common stock for the last three years. G Genzyme Corporation joined Dyax as joint venture partner Managing General Partner, Administration and G Complete Phase II 2001 2002 2003 G Gateway Associates, LP Chief Financial Officer Completed 3 of 4 dose cohorts in 48-patient Phase II EDEMA1 trial EDEMA1 study High Low High Low High Low G Susan B. Bayh, J.D. Lynn G. Baird, Ph.D.* Initiated Phase II EDEMA2 trial G Periodically observe James W. Fordyce SVP Development First Quarter $20.94 $6.56 $11.38 $3.10 $2.25 $1.52 G Orphan Drug designation granted in U.S. and Europe effects of repeat dosing in Phase II EDEMA2 Managing Partner, Robert C. Ladner, Ph.D. Second Quarter $19.99 $6.81 $ 4.68 $3.20 $4.90 $1.67 Fordyce & Gabrielson, LLC SVP and Chief DX-88/On-Pump Open Heart Surgery (CABG) study Third Quarter $21.24 $6.05 $ 4.20 $1.65 $7.50 $2.58 Mary Ann Gray, Ph.D. -

Cerezyme, INN-Imiglucerase

ANNEX I SUMMARY OF PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS 1 1. NAME OF THE MEDICINAL PRODUCT Cerezyme 400 Units Powder for concentrate for solution for infusion 2. QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION Each vial contains 400 units* of imiglucerase**. After reconstitution, the solution contains 40 units (approximately 1.0 mg) of imiglucerase per ml (400 U/10 ml). * An enzyme unit (U) is defined as the amount of enzyme that catalyses the hydrolysis of one micromole of the synthetic substrate para-nitrophenyl β-D-glucopyranoside (pNP-Glc) per minute at 37°C. ** Imiglucerase is a modified form of human acid β-glucosidase and is produced by recombinant DNA technology using a mammalian Chinese Hamster Ovary (CHO) cell culture, with mannose modification for targeting macrophages. Excipients: For the full list of excipients, see section 6.1. This medicinal product contains sodium and is administered in 0.9% sodium chloride intravenous solution (see section 6.6). After reconstitution, the solution contains 1.24 mmol sodium (400 U/10 mL). To be taken into consideration by patients on a controlled sodium diet. 3. PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Powder for concentrate for solution for infusion. Cerezyme is a white to off-white powder. 4. CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 Therapeutic indications Cerezyme (imiglucerase) is indicated for use as long-term enzyme replacement therapy in patients with a confirmed diagnosis of non-neuronopathic (Type 1) or chronic neuronopathic (Type 3) Gaucher disease who exhibit clinically significant non-neurological manifestations of the disease. The non-neurological manifestations of Gaucher disease include one or more of the following conditions: • anaemia after exclusion of other causes, such as iron deficiency • thrombocytopenia • bone disease after exclusion of other causes such as Vitamin D deficiency • hepatomegaly or splenomegaly 4.2 Posology and method of administration Disease management should be directed by physicians knowledgeable in the treatment of Gaucher disease. -

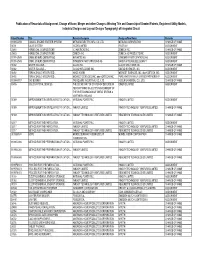

Publication of Recordals of Assignment, Change of Name

Publication of Recordals of Assignment, Change of Name, Merger and other Changes Affecting Title and Ownership of Granted Patents, Registered Utility Models, Industrial Designs and Lay-out Designs Topography) of Integrated Circuit Patent Number Title Patentee/Assignor Assignee/New Name Remarks 1199654059 COAXIAL ENGINE STARTER SYSTEM MITSUBA ELECTRIC MFG. CO. LTD. MITSUBA CORPORATION CHANGE OF NAME 31731 VALVE SYSTEM ISCOR LIMITED IPCOR NV ASSIGNMENT 25483 HERBICIDAL COMPOSITIONS ICI AMERICAS INC. ZENECA INC. CHANGE OF NAME 25483 HERBICIDAL COMPOSITIONS ZENECA INC. ZENECA AG PRODUCTS INC. ASSIGNMENT 1199142549 OXIME ETHERS DERIVATIVES NOVARTIS AG SYNGENTA PARTICIPATIONS AG ASSIGNMENT 1199142549 OXIME ETHERS DERIVATIVES SYNGENTA PARTICIPATIONS AG BAYER AKTIENGESELLSCHAFT ASSIGNMENT 31882 WATER SOLUBLE… GLAXO INC. GLAXO WELLCOME INC. CHANGE OF NAME 31882 WATER SOLUBLE… GLAXO WELLCOME INC. GILEAD SCIENCES, INC. ASSIGNMENT 31492 REPLACEABLE INTEGRATED… AMOS KORIN MIDWEST SCIENCES, INC. dba KORTECH, INC. ASSIGNMENT 31492 REPLACEABLE INTEGRATED… MIDWEST SCIENCES, INC. dba KORTECH, INC. PURE WATER FAMILY LIMITED PARTNERSHIP ASSIGNMENT 1199447817 GAS BURNER TRI-SQUARE INDUSTRIAL CO., LTD. HOSUN UNIVERSAL CO., LTD. CHANGE OF NAME 18495 LIQUID CRYSTAL DEVICES THE SECRETARY OF STATE FOR DEFENSE IN QINETIQ LIMITED ASSIGNMENT HER BRITTANIC MAJESTY'S GOVERNMENT OF THE UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT BRITAIN & NORTHERN IRELAND 31389 IMPROVEMENTS IN OR RELATING TO CATION… NATIONAL POWER PLC INNOGY LIMITED ASSIGNMENT 31389 IMPROVEMENTS IN OR RELATING TO CATION… -

Concert Management

CoNCERT Management Roger D. Tung President and Chief Executive Officer Roger D. Tung, Ph.D. is our scientific founder and has served as our President and Chief Executive Officer and as a mem- ber of our board of directors since April 2006. Before Concert, Dr. Tung was a founding scientist at Vertex Pharmaceuticals, a pharmaceutical company, where he was employed from 1989 to 2005, most recently as its Vice President of Drug Dis- covery. Prior to Vertex, he held various positions at Merck, Sharp & Dohme Research Laboratories, a global healthcare pro- vider, and The Squibb Institute for Medicinal Chemistry. He also serves as a member of the University of Wisconsin- Madison School of Pharmacy’s Board of Visitors, faculty mentor in the MIT IMPACT program, and strategic advisor to Long- wood Founder’s Fund. Dr. Tung received a B.A. in Chemistry from Reed College and a Ph.D. in Medicinal Chemistry at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Marc Becker Chief Financial Officer Mr. Marc Becker has served as our Chief Financial Officer since January 2018. Prior to joining Concert, Mr. Becker served as Senior Vice President and Chief Financial Officer at CRISPR Therapeutics from February 2016 to September 2017. Prior to joining CRISPR Therapeutics, Mr. Becker served as Chief Financial Officer and Senior Vice President of rEVO Biologics, a biopharmaceutical from January 2012 to February 2016. Before rEVO, Mr. Becker spent 10 years at Genzyme Corpora- tion, most recently serving as Finance Director for the UK and Ireland before returning to the United States to become the Vice President of Finance for Genzyme’s Renal and Endocrine business. -

PPCO Twist System

Connect. Collaborate. Contribute. NOVEMBER 2016 Sanofi Genzyme: Expanding Beyond Rare Disease Into Specialty Care p. 18 David Meeker, executive VP and head, Sanofi Genzyme Clinical Trials 26 Allergan R&D 30 Biopharma 32 DC Insider 10 How A Chief Medical Officer Why The Company Women In Bio: Looking CEO Corner 12 Changed The Data-sharing Is Focusing On An Through The Glass Ceiling Culture At J&J And Across “Open-Science Platform” Companies To Watch 16 The Industry Global Update 48 Bringing together the best of When it’s YOUR compound, every step matters. www.pfizercentreone.com API DRUG PRODUCT PC1-16-0005-8.25x10.875 in-Mar., 2016 © 2016 Pfizer Inc. All rights reserved. inVentiv Health. Genetically engineered for success in the new pharmaceutical world. inVentiv Health processes and capabilities can accelerate business performance. The fact is, getting a new drug across the fi nish line is hard work every day. But lately, the challenges have increased exponentially. Today, it’s not enough to simply obtain regulatory approval; market success is now as mission-critical as trial success. Smart outsourcing partners begin with the end in mind. That’s why inVentiv purpose-built an organization in which both clinical and commercial work together under one roof as teammates and colleagues, not distant relatives. From early development through product launch, they share knowledge capital, data and insights. Our superior clinical trial design combined with highly effective commercial launch capabilities creates a unique environment in which processes and systems are constantly being challenged and evolved with an eye towards greater effi ciency, higher quality and, of course, getting to market faster. -

China Rare Disease Market: Large and Untapped Opportunity

Delivering Life-Changing Therapies to Patients June 2019 Mission and Vision To be a global biopharmaceutical company delivering life-changing therapeutics built upon a foundation in China CANbridge Pharmaceuticals 2 Investment Highlights Pioneer in Balanced Leverage Comprehensive Deep, Advanced China’s Orphan Business Technology Global Solution Portfolio Drug Market Model Partnerships Provider Leadership: Foundation: Leverage Portfolio: Strategy: Mission: Sole Deputy Director near term revenue from 1 marketed, 2 near- Partner with leading To be a global General from industry oncology to support commercial, 5 rare academic institutions biopharmaceutical for China’s Alliance for orphan drug disease and 2 and biopharma company delivering Rare Disease (CARD) development oncology clinical companies life-changing candidates therapeutics built upon Experience: Future: Execution: a foundation in China CANbridge Team The premier partner for De-risked: Partnership with Wuxi launched first rare China and global rare Most candidates target and GC Pharma to disease drug in China disease drug commercially validated prosecute product development pathways candidates in China Visionary Management Team Thought leaders and political influencers directly involved in shaping the future of China’s orphan drug market CANbridge Pharmaceuticals 3 World Class Leadership Team with Deep Experience James Xue, Ph.D., M.B.A Ben Wu, M.B.A. • Brings significant orphan drug experience from across Asia Founder, Chairman, Head of Rare • Joined Genzyme in 2008 to pioneer -

Exploring Technological Change in the German Pharmaceutical Industry

Exploring technological change in the German pharmaceutical industry A history-friendly model of technological change and technology adoption in a science-based industry Zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Doktors der Wirtschaftswissenschaften (Dr. rer. pol.) von der Fakultät für Wirtschaftswissenschaften der Universität Fridericiana zu Karlsruhe genehmigte Dissertation von lic. rer. pol. Iciar Dominguez Lacasa Tag der mündlichen Prüfung: 17. Juli 2005 Referent: Prof. Dr. Hariolf Grupp Koreferent: Prof. Dr. Hagen Lindstädt E R K L Ä R U N G (gemäß §4, Abs. 4 der Promotionsordnung vom 21. April 1989) Ich versichere wahrheitsgemäß, die Dissertation bis auf die in der Abhandlung angegebe Hilfe selbständig angefertigt, alle benutzten Hilfsmittel vollständig und genau angegeben und genau kenntlich gemacht zu haben, was aus Arbeiten anderer und aus eigenen Veröffentlichungen unverändert oder mit Abänderungen entnommen wurde. Acknowledgements The driving ideas for this project came from a working paper my supervisor gave me from the Danish Research Unit for Industrial Dynamics (DRUID). Already on the first pages I found a family of economic terms that were quite new for an economist with a strong neo-classical background like me: complex dynamics, behavioural patterns, invention, innovation, selection mechanisms, simulation model etc. Both, my curiosity to find out more about these terms and my interest for the economics of technological change motivated the learning process I have been involved in the last 4 years. This document is the result of this intellectual adventure. There are a number of people that have been important and I would like to thank here. First, I would like to express my special thanks to Hariolf Grupp for providing me with enough intellectual freedom and guidance when I needed it to complete this effort. -

Client List LATEST

Client number client name country area code client comments corporate number 1382 3 FHEA LAB AD GER SONER C11612 1017 3M MEDICAL DEPARTMENT USA ST PAUL 785 A.H. MARNE & CO LTD UK BRADFORD C11634 1781 ART JAPAN INC. JAP TOKYO 103 Applied Ananlytical Immagary Inc. 644 ABBOTT LABORATORIES LTD US ilILLINOIS Abbott Park C10042 1789 ACTIVE BIOTECH RESEARCH SWE LUND Lund Research Centre AB 1244 AGAN CHEMICAL ITA C10693 1245 AGOURON PHARMACEUTICALS INC. USA SAN DIEGO C10007 774 AGREVO UK LTD UK Now use 1849 Aventis CropScience 1302 AGRITECH UK LIMITED UK SELBOURNE C11646 619 AGRO KAHEAHO COMPANY LTD JAP TOKYO C10854 1773 AIR PRODUCTS AND CHEMICALS INC USA USA C10007 702 AJIMOMOTO CO INC JAP C10323 1946 AJIMOMOTO PHARMACEUTICALS EURO UK REDHILL EUROPE LTD 1043 AKED INTERVET NET C10211 1710 AKZO NOBEL SWE STENLUNGEUN C10210 254 ALBRIGHT & WILSON UK LIMITED UK HENLEY C11661 ALEEN LABORATORIES INC USA FORT WORTH C10663 1747 ALIZYME THERAPEUTICSLTD UK CAMBRIDGE C14475 ALLELEX BIO PHARMACEUTICALS CAN ONTARIO C14103 804 ALLERMAN UK C10903 2791 ALLERCENE LTD RAMAT ISRAEL 1725 ALLERGY THERAPEUTICS LTD UK WORTHING 635 ALMIRALL SPA BARCELONA C10320 1741 ALPHARMA AU NOR OSLO C23276 628 AMERICAN CYANAMID COMPANY USA C10016 1838 AMRAD OPERATIONS PTY LTD AUS RICHMOND C10135 1702 AMVAC CHEMICAL CORPORATIONUSA USA CITY OF CO City of COMMERCE, California C10814 1184 AMYLIN EUROPE LTD UK OXFORD C10020 1070 ANCARE NEW ZEALAND LTD NZ AUCKLAND 607 ANT. INTERNATIONAL LTD UK SUDBURY C11694 1622 ANTISEPTICA GmbH GER 1070 AORTECH EUROPE LTD UK LEEDS 1098 APHTON CORPORATION USA WOODLAND CITY C10916 1737 APOTEX RESEARCH INC. CAN ONTARIO C14502 1628 AQUAMARINE (LONDON) LTD UK HOUNSLOW 1711 ARIAD PHARMACEUTICALS INC USA MASS. -

Annual Report on Form 20-F 2018

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 20-F (Mark One) ☐ REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OR (g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 or ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2018 Or ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Or ☐ SHELL COMPANY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Date of event requiring this shell company report For the transition period from to Commission File Number: 001-31368 Sanofi (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) N/A (Translation of registrant’s name into English) France (Jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) 54, Rue La Boétie, 75008 Paris, France (Address of principal executive offices) Karen Linehan, Executive Vice President Legal Affairs and General Counsel 54, Rue La Boétie, 75008 Paris, France. Fax: 011 + 33 1 53 77 43 03. Tel: 011 + 33 1 53 77 40 00 (Name, Telephone, E-mail and/or Facsimile number and Address of Company Contact Person) Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class: Name of each exchange on which registered: American Depositary Shares, each representing one half of one ordinary share, par value€2 per share NASDAQ Global Select Market Ordinary shares, par value€2 per share NASDAQ Global Select Market* Contingent Value Rights NASDAQ Global Market Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None The number of outstanding shares of each of the issuer’s classes of capital or common stock as of December 31, 2018 was: Ordinary shares: 1,245,454,385 Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. -

Development of Therapeutic Antibodies for the Treatment Of

Lu et al. Journal of Biomedical Science (2020) 27:1 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12929-019-0592-z REVIEW Open Access Development of therapeutic antibodies for the treatment of diseases Ruei-Min Lu1, Yu-Chyi Hwang1, I-Ju Liu1†, Chi-Chiu Lee1†, Han-Zen Tsai1†, Hsin-Jung Li1 and Han-Chung Wu1,2* Abstract It has been more than three decades since the first monoclonal antibody was approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (US FDA) in 1986, and during this time, antibody engineering has dramatically evolved. Current antibody drugs have increasingly fewer adverse effects due to their high specificity. As a result, therapeutic antibodies have become the predominant class of new drugs developed in recent years. Over the past five years, antibodies have become the best-selling drugs in the pharmaceutical market, and in 2018, eight of the top ten bestselling drugs worldwide were biologics. The global therapeutic monoclonal antibody market was valued at approximately US$115.2 billion in 2018 and is expected to generate revenue of $150 billion by the end of 2019 and $300 billion by 2025. Thus, the market for therapeutic antibody drugs has experienced explosive growth as new drugs have been approved for treating various human diseases, including many cancers, autoimmune, metabolic and infectious diseases. As of December 2019, 79 therapeutic mAbs have been approved by the US FDA, but there is still significant growth potential. This review summarizes the latest market trends and outlines the preeminent antibody engineering technologies used in the development of therapeutic antibody drugs, such as humanization of monoclonal antibodies, phage display, the human antibody mouse, single B cell antibody technology, and affinity maturation.