Translation Today

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

APPENDIX-V FOREIGN CONTRIBUTION (REGULATION) ACT, 1976 During the Emergency Regime in the Mid-1970S, Voluntary Organizations

APPENDIX-V FOREIGN CONTRIBUTION (REGULATION) ACT, 1976 During the Emergency Regime in the mid-1970s, voluntary organizations played a significant role in Jayaprakash Narayan's (JP) movement against Mrs. Indira Gandhi. With the intervention of voluntary organizations, JP movement received funds from external sources. The government became suspicious of the N GOs as mentioned in the previous chapter and thus appointed a few prominent people in establishing the Kudal Commission to investigate the ways in which JP movement functioned. Interestingly, the findings of the investigating team prompted the passage of the Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Act during the Emergency Period. The government prepared a Bill and put it up for approval in 1973 to regulate or control the use of foreign aid which arrived in India in the form of donations or charity but it did not pass as an Act in the same year due to certain reasons undisclosed. However, in 1976, Foreign Contribution (Regulation) Act was introduced to basically monitor the inflow of funds from foreign countries by philanthropists, individuals, groups, society or organization. Basically, this Act was enacted with a view to ensure that Parliamentary, political or academic institutions, voluntary organizations and individuals who are working in significant areas of national life may function in a direction consistent with the values of a sovereign democratic republic. Any organizations that seek foreign funds have to register with the Ministry of Home Affairs, FCRA, and New Delhi. This Act is applicable to every state in India including organizations, societies, companies or corporations in the country. NGOs can apply through the FC-8 Form for a permanent number. -

ಕ ೋವಿಡ್ ಲಸಿಕಾಕರಣ ಕ ೋೇಂದ್ರಗಳು (COVID VACCINATION CENTRES) Sl No District CVC Na

ಕ ೋ풿蓍 ಲಕಾಕರಣ ಕ ೋᲂ飍ರಗಳು (COVID VACCINATION CENTRES) Sl No District CVC Name Category 1 Bagalkot SC Karadi Government 2 Bagalkot SC TUMBA Government 3 Bagalkot Kandagal PHC Government 4 Bagalkot SC KADIVALA Government 5 Bagalkot SC JANKANUR Government 6 Bagalkot SC IDDALAGI Government 7 Bagalkot PHC SUTAGUNDAR COVAXIN Government 8 Bagalkot Togunasi PHC Government 9 Bagalkot Galagali Phc Government 10 Bagalkot Dept.of Respiratory Medicine 1 Private 11 Bagalkot PHC BENNUR COVAXIN Government 12 Bagalkot Kakanur PHC Government 13 Bagalkot PHC Halagali Government 14 Bagalkot SC Jagadal Government 15 Bagalkot SC LAYADAGUNDI Government 16 Bagalkot Phc Belagali Government 17 Bagalkot SC GANJIHALA Government 18 Bagalkot Taluk Hospital Bilagi Government 19 Bagalkot PHC Linganur Government 20 Bagalkot TOGUNSHI PHC COVAXIN Government 21 Bagalkot SC KANDAGAL-B Government 22 Bagalkot PHC GALAGALI COVAXIN Government 23 Bagalkot PHC KUNDARGI COVAXIN Government 24 Bagalkot SC Hunnur Government 25 Bagalkot Dhannur PHC Covaxin Government 26 Bagalkot BELUR PHC COVAXINE Government 27 Bagalkot Guledgudd CHC Covaxin Government 28 Bagalkot SC Chikkapadasalagi Government 29 Bagalkot SC BALAKUNDI Government 30 Bagalkot Nagur PHC Government 31 Bagalkot PHC Malali Government 32 Bagalkot SC HALINGALI Government 33 Bagalkot PHC RAMPUR COVAXIN Government 34 Bagalkot PHC Terdal Covaxin Government 35 Bagalkot Chittaragi PHC Government 36 Bagalkot SC HAVARAGI Government 37 Bagalkot Karadi PHC Covaxin Government 38 Bagalkot SC SUTAGUNDAR Government 39 Bagalkot Ilkal GH Government -

Technology and Engineering International Journal of Recent

International Journal of Recent Technology and Engineering ISSN : 2277 - 3878 Website: www.ijrte.org Volume-7 Issue-5C, FEBRUARY 2019 Published by: Blue Eyes Intelligence Engineering and Sciences Publication d E a n n g y i n g o e l e o r i n n h g c e T t n e c Ijrt e e E R X I N P n f L O I O t T R A o e I V N O l G N r IN n a a n r t i u o o n J a l www.ijrte.org Exploring Innovation Editor-In-Chief Chair Dr. Shiv Kumar Ph.D. (CSE), M.Tech. (IT, Honors), B.Tech. (IT) Director, Blue Eyes Intelligence Engineering & Sciences Publication, Bhopal (M.P.), India Professor, Department of Computer Science & Engineering, Lakshmi Narain College of Technology-Excellence (LNCTE), Bhopal (M.P.), India Associated Editor-In-Chief Chair Dr. Dinesh Varshney Director of College Development Counseling, Devi Ahilya University, Indore (M.P.), Professor, School of Physics, Devi Ahilya University, Indore (M.P.), and Regional Director, Madhya Pradesh Bhoj (Open) University, Indore (M.P.), India Associated Editor-In-Chief Members Dr. Hai Shanker Hota Ph.D. (CSE), MCA, MSc (Mathematics) Professor & Head, Department of CS, Bilaspur University, Bilaspur (C.G.), India Dr. Gamal Abd El-Nasser Ahmed Mohamed Said Ph.D(CSE), MS(CSE), BSc(EE) Department of Computer and Information Technology , Port Training Institute, Arab Academy for Science ,Technology and Maritime Transport, Egypt Dr. Mayank Singh PDF (Purs), Ph.D(CSE), ME(Software Engineering), BE(CSE), SMACM, MIEEE, LMCSI, SMIACSIT Department of Electrical, Electronic and Computer Engineering, School of Engineering, Howard College, University of KwaZulu- Natal, Durban, South Africa. -

Lives in Poetry

LIVES IN POETRY John Scales Avery March 25, 2020 2 Contents 1 HOMER 9 1.1 The little that is known about Homer's life . .9 1.2 The Iliad, late 8th or early 7th century BC . 12 1.3 The Odyssey . 14 2 ANCIENT GREEK POETRY AND DRAMA 23 2.1 The ethical message of Greek drama . 23 2.2 Sophocles, 497 BC - 406 BC . 23 2.3 Euripides, c.480 BC - c.406 BC . 25 2.4 Aristophanes, c.446 BC - c.386 BC . 26 2.5 Sapho, c.630 BC - c.570 BC . 28 3 POETS OF ANCIENT ROME 31 3.1 Lucretius, c.90 BC - c.55 BC . 31 3.2 Ovid, 43 BC - c.17 AD . 33 3.3 Virgil, 70 BC - 19 AD . 36 3.4 Juvenal, late 1st century AD - early 2nd century AD . 40 4 THE GOLDEN AGE OF CHINESE POETRY 45 4.1 The T'ang dynasty, a golden age for China . 45 4.2 Tu Fu, 712-770 . 46 4.3 Li Po, 701-762 . 48 4.4 Li Ching Chao, 1081-c.1141 . 50 5 JAPANESE HAIKU 55 5.1 Basho . 55 5.2 Kobayashi Issa, 1763-1828 . 58 5.3 Some modern haiku in English . 60 6 POETS OF INDIA 61 6.1 Some of India's famous poets . 61 6.2 Rabindranath Tagore, 1861-1941 . 61 6.3 Kamala Surayya, 1934-2009 . 66 3 4 CONTENTS 7 POETS OF ISLAM 71 7.1 Ferdowsi, c.940-1020 . 71 7.2 Omar Khayyam, 1048-1131 . 73 7.3 Rumi, 1207-1273 . -

Waromung an Ao Naga Village, Monograph Series, Part VI, Vol-I

@ MONOGRAPH CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 No. I VOLUME-I MONOGRAPH SERIES Part VI In vestigation Alemchiba Ao and Draft Research design, B. K. Roy Burman Supervision and Editing Foreword Asok Mitra Registrar General, InOla OFFICE OF THE REGISTRAR GENERAL, INDIA WAROMUNG MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS (an Ao Naga Village) NEW DELHI-ll Photographs -N. Alemchiba Ao K. C. Sharma Technical advice in describing the illustrations -Ruth Reeves Technical advice in mapping -Po Lal Maps and drawings including cover page -T. Keshava Rao S. Krishna pillai . Typing -B. N. Kapoor Tabulation -C. G. Jadhav Ganesh Dass S. C. Saxena S. P. Thukral Sudesh Chander K. K. Chawla J. K. Mongia Index & Final Checking -Ram Gopal Assistance to editor in arranging materials -T. Kapoor (Helped by Ram Gopal) Proof Reading - R. L. Gupta (Final Scrutiny) P. K. Sharma Didar Singh Dharam Pal D. C. Verma CONTENTS Pages Acknow ledgement IX Foreword XI Preface XIII-XIV Prelude XV-XVII I Introduction ... 1-11 II The People .. 12-43 III Economic Life ... .. e • 44-82 IV Social and Cultural Life •• 83-101 V Conclusion •• 102-103 Appendices .. 105-201 Index .... ... 203-210 Bibliography 211 LIST OF MAPS After Page Notional map of Mokokchung district showing location of the village under survey and other places that occur in the Report XVI 2 Notional map of Waromung showing Land-use-1963 2 3 Notional map of Waromung showing nature of slope 2 4 (a) Notional map of Waromung showing area under vegetation 2 4 (b) Notional map of Waromung showing distribution of vegetation type 2 5 (a) Outline of the residential area SO years ago 4 5 (b) Important public places and the residential pattern of Waromung 6 6 A field (Jhurn) Showing the distribution of crops 58 liST OF PLATES After Page I The war drum 4 2 The main road inside the village 6 3 The village Church 8 4 The Lower Primary School building . -

District and KVK Profile, 28-6-2012

District Agricultural Profile Bagalkot District Area 6575 Sq. Kms. (658877 ha) Rural population 1173372 Net sown area 468276 ha Net irrigated area 228757 ha Soil Type Medium black, Red Climatic Zone Northern Dry Zone-III of Karnataka agroclimatic classification Major crops Sugarcane, Groundnut, Maize, Greengram, Jawar, Bengalgram and Wheat Major fruit crops Pomegranate, Sapota and Lime LIVESTOCK POPULATION Particulars No 1. Cattle 305217 2. Buffalo 252544 3. Goats 431719 4. Sheep 673602 5. Horses & Ponies 200 6. Mules - 7. Donkeys 136 8. Pigs 24922 9. Fowls - 10. Ducks - 11. Other Poultries 1179225 12. Rabbits 263 Total 2867828 BREEDABLE CATTLE & BUFFALOES Female Cattle Young stock 43000 Adults 61000 Total 104000 Female Buffalo Young stock 36000 Adults 51000 Total 87000 Male Indigenous 55000 Cross Bred 38000 Total 93000 Female Indigenous 46000 Cross Bred 28000 Total 74000 Total Indigenous 101000 Total Cross Bred 66000 Grand Total 358000 Major Field crops CEREALS : A=Area (ha), P=Production (tonnes), Y=Yield (Kg/ha) Year Jowar Bajra Maize Wheat A P Y A P Y A P Y A P Y 2001 -02 170489 125015 772 15169 11519 799 38333 114252 3137 25855 34969 1424 2002 -03 162812 107887 698 24007 7171 314 30456 96747 3344 23327 32386 1461 2003 -04 138744 20209 153 15454 8153 555 27906 88775 3349 15300 18327 1261 2004 -05 155574 50947 681 50947 32970 681 51022 178194 3676 21202 32903 1634 2005 -06 137541 165480 1266 44354 54674 1298 55414 222134 4220 21840 34948 1684 2006 -07 129000 68927 562 39194 13233 355 51091 188747 3889 20992 27344 1371 2007 -08 133034 -

The Number of Ph.Ds Awarded Per Teacher During the Last Five Years S

The Number of Ph.Ds Awarded per Teacher during the last five Years Name of the Name of the Name of the Ph.D Year of S.No Title of Thesis Supervisor Department scholar Award 2014-15 Analysis of Nutritional Status Anthropometrical Exercise Physiological and K.Silambu Selvi Nov-14 1. Physiology & Biochemical Parameters Nutrition Among Rural and Urban Postmenopausal Women. Effect of Spinning Cycle Exercise and Protein Exercise Supplementation on Lipid 2014 2. Physiology & V.Vijay Profile Testosterone Nutrition Level in Obese Men Software Professionals. Effect of Specific Dr.Grace Helina Nutritional Supplementation Exercise P.Amarnath Desupplementation and 2014 3. Physiology & Resupplementation on Nutrition Anemic Profile Status Among College Women Effects of Selected Drill Practices and Aerobic Exercise on Selected Physical Motor Physiological Mr.S.Jacop Jul-15 4. Education Biochemical and Hematological Variables Among College Men Football Players Quantification of Selected Physiological Hematological and Biochemical Responses to Isolated and Combined Physical Dr.S.Thirumalaikumar D.Jayabal Training of Yogic Nov-14 5. Education Practice Jogging and Walking Among University Men Students Effect of Combined and Isolated Yogic Practiced and Yogic Diet on Selected Physiological Yoga A.Pushpalatha Apr-15 6. and Psychological Variables Among Obese Engineering College Women Students Effect of Yogic Practices and Therapeutic Exercises on Selected Physiological and Yoga S.Lakshmikandhan Sep-14 7. Clinical and Psychological Variables Among Back Ache Affected men Effect of Yogic Practices and Therapeutic Exercises on Selected Yoga E.Sudha Physiological , Apr-15 8. Biochemical and Psychological Variables Dr.R.Elangovan Among Police Men Effect of Varied Yogic Practices on Selected Physiological, Yoga V.Subbulakshimi Hematological and Mar-15 9. -

Farmers' Awareness Level About ICT Tools and Services in Karnataka

5870 Research Note Journal of Extension Education Vol. 29 No. 2, 2017 DOI:https://doi.org/10.26725/JEE.2017.2.29.5870-5874 Farmers’ Awareness Level about ICT Tools and Services in Karnataka Manjuprakash1, H. Philip2 and N. Sriram3 ABSTRACT A study was undertaken to elicit the farmers’ awareness about ICT tools and services in Karnataka. The study was conducted in Koppal district of Karnataka state with 120 respondents. It was found that more than half of the respondents had medium level of awareness on ICT tools and services. Majority of the respondents were aware of mobile advisory services by Agricultural Produce Market Committee (APMC). Almost two- thirds of the respondents were aware of KCC (Kisan Call Centre) service. Slightly less than two-fourths of the respondents were aware of touch screen kiosks. The paper also discusses the awareness level of farmers on many other ICT tools. Keywords : ICT, Mobile advisory; Social Networking; Awareness; Farmer; Karnataka In the recent past, agriculture the followers are posted and updated. sector has become increasingly Though there are number of ICT information-dependent, requiring a initiatives available to cater various wide range of scientific and technical solutions to the agricultural problems, information for effective decision-making farmers are not aware of several by the farming community (Cash, existing services. This study assesses 2001).The role of ICTs as a medium the awareness and knowledge of the of dissemination of information and farmers on ICT schemes and projects in knowledge in agricultural development Karnataka has been widely recognized and discussed in the existing literature METHODOLOGY (Rao, 2008). -

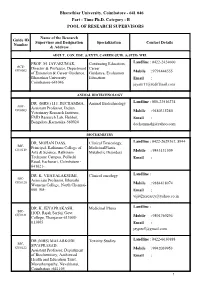

Bharathiar University, Coimbatore - 641 046 Part - Time Ph.D

Bharathiar University, Coimbatore - 641 046 Part - Time Ph.D. Category - B POOL OF RESEARCH SUPERVISORS Name of the Research Guide ID Supervisor and Designation Specialization Contact Details Number & Address ADULT . CON. EDU. & EXTN. CAREER GUID. & STUD. WEL PROF. M. JAYAKUMAR, Continuing Education, Landline : 0422-2424600 ACE- Director & Professor, Department Career GU0002 of Extension & Career Guidance, Guidance, Evaluation Mobile : 9791444555 Bharathiar University Education Email : Coimbatore-641046 [email protected] ANIMAL BIOTECHNOLOGY DR. (MRS.) H.J. DECHAMMA, Animal Biotechnology Landline : 080-23516274 ABT- Assistant Professor, Indian GU0003 Veterinary Research Institute, Mobile : 9480315280 FMD Research Lab, Hebbal, Email : Bangalore,Karnataka-560024 [email protected] BIOCHEMISTRY DR. MOHAN DASS, Clinical Toxicology, Landline : 0422-2629367, 8944 BIC- Principal, Rathinam College of MedicinalPlants, GU0119 Arts & Science, Rathinam Metabolic Disorders Mobile : 9843131509 Techzone Campus, Pollachi Email : Road, Eachanari, Coimbatore - 641021- DR. K. VIJAYALAKSHMI, Clinical oncology Landline : BIC- Associate Professor, Bharathi GU0120 Womens College, North Chennai- Mobile : 9884418074 600 108- Email : [email protected] DR. K. JEYAPRAKASH, Medicinal Plants Landline : BIC- HOD, Rajah Serfoji Govt. GU0121 College, Thanjavur-613005- Mobile : 9894769294 613005 Email : [email protected] DR.(MRS) MALARKODI Toxicity Studies Landline : 0422-6630888 BIC- SIVAPRASAD, GU0122 Assistant Professor, Department Mobile : 9942039953 of Biochemistry, Aashirwad Email : Health and Education Trust, Mavuthampathy, Navakkarai, Coimbatore -641105 1 DR. P. SUMATHI, Clinical Bio-Chemistry Landline : 044-27454863 BIC- Assistant Professor, Govt. GU0123 College for Women, Krishnagiri- Mobile : 9444151677 635001 Email : DR. M. JEYARAJ, Plant Bio-Chemistry Landline : BIC- Lecturer, Dept. of Biochemistry, GU0124 Government of Arts College, Mobile : 9787059193 Paramakudi , Ramnad Dt., Email : Tamilnadu-623707 [email protected] [email protected] DR. -

India Progressive Writers Association; *7:Arxicm

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 124 936 CS 202 742 ccpp-.1a, CsIrlo. Ed. Marxist Influences and South Asaan li-oerazure.South ;:sia Series OcasioLal raper No. 23,Vol. I. Michijar East Lansing. As:,an Studies Center. PUB rAIE -74 NCIE 414. 7ESF ME-$C.8' HC-$11.37 Pius ?cstage. 22SCrIP:0:", *Asian Stud,es; 3engali; *Conference reports; ,,Fiction; Hindi; *Literary Analysis;Literary Genres; = L_tera-y Tnfluences;*Literature; Poetry; Feal,_sm; *Socialism; Urlu All India Progressive Writers Association; *7:arxicm 'ALZT:AL: Ti.'__ locument prasen-ls papers sealing *viithvarious aspects of !',arxi=it 2--= racyinfluence, and more specifically socialisr al sr, ir inlia, Pakistan, "nd Bangladesh.'Included are articles that deal with _Aich subjects a:.the All-India Progressive Associa-lion, creative writers in Urdu,Bengali poets today Inclian poetry iT and socialist realism, socialist real.Lsm anu the Inlion nov-,-1 in English, the novelistMulk raj Anand, the poet Jhaverchan'l Meyhani, aspects of the socialistrealist verse of Sandaram and mash:: }tar Yoshi, *socialistrealism and Hindi novels, socialist realism i: modern pos=y, Mohan Bakesh andsocialist realism, lashpol from tealist to hcmanisc. (72) y..1,**,,A4-1.--*****=*,,,,k**-.4-**--4.*x..******************.=%.****** acg.u.re:1 by 7..-IC include many informalunpublished :Dt ,Ivillable from othr source r.LrIC make::3-4(.--._y effort 'c obtain 1,( ,t c-;;,y ava:lable.fev,?r-rfeless, items of marginal * are oft =.ncolntered and this affects the quality * * -n- a%I rt-irodu::tior:; i:";IC makes availahl 1: not quali-y o: th< original document.reproductiour, ba, made from the original. -

CRITICAL ANALYSIS of PROTAGONISTS of MULK RAJ ANAND’S NOVELS Dr

International Journal of Technical Research and Applications e-ISSN: 2320-8163, www.ijtra.com Special Issue 10 (Nov-Dec 2014), PP. 75-77 CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF PROTAGONISTS OF MULK RAJ ANAND’S NOVELS Dr. Shashi Yadav Assistant Professor, Department of Humanities Barkatullah, University Institute of Technology Bhopal, (M.P.) India, Pincode 462026 [email protected] Abstract: Mulk Raj Anand in his novels draws character known during my childhood and youth. And I was only from the real society around him, people whom he happens to repaying the debt of gratitude I owed them for much of the know in actual life. During his life’s journey, some character even inspiration they had given me to mature into manhood, when I haunt the novelist and compel him to write about them. Speaking began to interpret. .. They were flesh of my flesh and blood of as a novelist, he said that he came across people who had rather my blood, and obsessed me in the way in which certain human forced him to put them down in his novels. Through out his literary career, Anand wrote about real people whom he knew beings obsess an artist's soul. And I was doing no more than quite closely. what a writer does when seeks to interpret the truth from the Key words: Untouchable, realism, protagonist, social realities of his life.[2] conflict, humanism, downtrodden. One of the social concerns that recurs frequently in his novels is the inequality between the wealthy and the poor. He I. INTRODUCTION expresses his deep sorrow and sympathy for the unfortunate All characters of Mulk Raj Anand's novels are remarkable poor and their inability to cope with the circumstances. -

The Lawu Languages

The Lawu languages: footprints along the Red River valley corridor Andrew Hsiu ([email protected]) https://sites.google.com/site/msealangs/ Center for Research in Computational Linguistics (CRCL), Bangkok, Thailand Draft published on December 30, 2017; revised on January 8, 2018 Abstract In this paper, Lawu (Yang 2012) and Awu (Lu & Lu 2011) are shown to be two geographically disjunct but related languages in Yunnan, China forming a previously unidentified sub-branch of Loloish (Ngwi). Both languages are located along the southwestern banks of the Red River. Additionally, Lewu, an extinct language in Jingdong County, may be related to Lawu, but this is far from certain due to the limited data. The possible genetic position of the unclassified Alu language in Lüchun County is also discussed, and my preliminary analysis of the highly limited Alu data shows that it is likely not a Lawu language. The Lawu (alternatively Lawoid or Lawoish) branch cannot be classified within any other known branch or subgroup or Loloish, and is tentatively considered to be an independent branch of Loloish. Further research on Lawu languages and surrounding under-documented languages would be highly promising, especially on various unidentified languages of Jinping County, southern Yunnan. Table of contents Abstract 1. Introduction 2. Lawu 3. Awu 4. Lewu Yao: a possible relative of Lawu 5. Alu: a Lalo language rather than a Lawu language 6. Conclusions 7. Final remarks: suggestions for future research References Appendix 1: Comparative word list of Awu, Lawu, and Proto-Lalo Appendix 2: Phrase list of Lewu Yao Appendix 3: Comparative word list of Yi lects of Lüchun County 1 1.