The Use of Place in Wisconsin Craft Beer Marketing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2015 Festival Organizers and Staff

Welcome from the President ELCOME TO THE 29TH ANNUAL Great Taste of the Midwest. At a time when we probably should be over- whelmed by the explosive growth of the craft beer industry, we are too busy trying to figure Wout how to make this event a better experience for all. To that end, we are excited that we have maintained the same foot- print as we’ve had in past years, but have added more brewer space, by moving our merch tents and adding a few new tents to a previously restricted staff only area of the park (inside the “loop road”). This allows us bring in some new brewers while continuing to bring back the brewers that you come to expect to see at the Great Taste of the Midwest. I would like to thank Great Taste Chairman, Mark Garthwaite and the multitude of volunteers that make this event happen. We are all very proud that this is the only event of this size that is run by a 100% volunteer effort. Their passion for beer is a large part of what makes a volunteer effort of this size a success. I would also like to thank all of the Brewers that come to the Great Taste of the Midwest. All of “our” passion for beer flows from their passion. As the event has grown and produced more return Brewers each year, we’ve come to think of the Brewers as family coming home every year on the second Saturday in August. Sadly, I have to acknowledge the passing of several MHTG members since the last Great Taste. -

August 13, 2011 Olin Park | Madison, WI 25Years of Great Taste

August 13, 2011 Olin Park | Madison, WI 25years of Great Taste MEMORIES FOR SALE! Be sure to pick up your copy of the limited edition full-color book, The Great Taste of the Midwest: Celebrating 25 Years, while you’re here today. You’ll love reliving each and every year of the festi- val in pictures, stories, stats, and more. Books are available TODAY at the festival souve- nir sales tent, and near the front gate. They will be available online, sometime after the festival, at the Madison Homebrewers and Tasters Guild website, http://mhtg.org. WelcOMe frOM the PresIdent elcome to the Great taste of the midwest! this year we are celebrating our 25th year, making this the second longest running beer festival in the country! in celebration of our silver anniversary, we are releasing the Great taste of the midwest: celebrating 25 Years, a book that chronicles the creation of the festival in 1987W and how it has changed since. the book is available for $25 at the merchandise tent, and will also be available by the front gate both before and after the event. in the forward to the book, Bill rogers, our festival chairman, talks about the parallel growth of the craft beer industry and our festival, which has allowed us to grow to hosting 124 breweries this year, an awesome statistic in that they all come from the midwest. we are also coming close to maxing out the capacity of the real ale tent with around 70 cask-conditioned beers! someone recently asked me if i felt that the event comes off by the seat of our pants, because sometimes during our planning meetings it feels that way. -

List of Suppliers As of April 19, 2019

List of Suppliers as of April 19, 2019 1006547746 1 800 WINE SHOPCOM INC 525 AIRPARK RD NAPA CA 945587514 7072530200 1018334858 1 SPIRIT 3830 VALLEY CENTRE DR # 705-903 SAN DIEGO CA 921303320 8586779373 1017328129 10 BARREL BREWING CO 62970 18TH ST BEND OR 977019847 5415851007 1018691812 10 BARREL BREWING IDAHO LLC 826 W BANNOCK ST BOISE ID 837025857 5415851007 1017363560 10TH MOUNTAIN WHISKEY AND SPIRITS COMPANY LLC 500 TRAIL GULCH RD GYPSUM CO 81637 9703313402 1001989813 14 HANDS WINERY 660 FRONTIER RD PROSSER WA 993505507 4254881133 1035490358 1849 WINE COMPANY 4441 S DOWNEY RD VERNON CA 900582518 8185813663 1040236189 2 BAR SPIRITS 2960 4TH AVE S STE 106 SEATTLE WA 981341203 2064024340 1006562982 21ST CENTURY SPIRITS 6560 E WASHINGTON BLVD LOS ANGELES CA 900401822 1016418833 220 IMPORTS LLC 3792 E COVEY LN PHOENIX AZ 850505002 6024020537 1008951900 3 BADGE MIXOLOGY 880 HANNA DR AMERICAN CANYON CA 945039605 7079968463 1016333536 3 CROWNS DISTRIBUTORS 534 MONTGOMERY AVE STE 202 OXNARD CA 930360815 8057972127 1039967515 360 GLOBAL WINE COMPANY INC 3 COLUMBUS CIR FL 15 NEW YORK NY 100198716 2128593520 1040217257 3FWINE LLC 21995 SW FINNIGAN HILL RD HILLSBORO OR 971238828 5035363083 1039154000 503 DISTILLING LLC 275 BEAVERCREEK RD STE 149 OREGON CITY OR 970454171 5038169088 1039152554 5STAR ESPIRIT LLC 1884 THE ALAMEDA SAN JOSE CA 951261733 2025587077 1038066492 8 BIT BREWING COMPANY 26755 JEFFERSON AVE STE F MURRIETA CA 925626941 9516772322 1014665400 8 VINI INC 1250 BUSINESS CENTER DR SAN LEANDRO CA 945772241 5106758888 1014476771 88 -

Curds 101 I Melt with You History Made Here Swiss Miss Dining Alfresco Picker’S Paradise Family Business the Perfect Pair and More

Curds 101 I Melt With You History Made Here Swiss Miss Dining Alfresco Picker’s Paradise Family Business The Perfect Pair and more... 2 3 4 In Green County, we believe there’s artistry to living the great life—a way of life built on a proud Swiss heritage, with creativity and precision as hallmarks of all that we do. Our cheesemakers and brewers are artists who pour their personal passion, attention to detail and craftsmanship into every wedge, wheel and block of cheese; and every bottle and keg of beer. From our rich bounty of locally crafted food and beer, to the artistry of barn quilts. Or the art of the landscape—with crops planted in orderly strips echoing the contours of the land to minimize erosion. Dairy cattle grazing the rolling hills. Farmers—artists turning grass into milk. The artistry of local heritage expressed through music, dance, and cuisine. Our legacy, our way of life. From the hands and hearts of our entire community of master artisans to the heart and soul of you and your family. there’s an art to it. PHOTOS AND CREDITS Front cover: Josh and Jessica Mayer at New Glarus Hotel (Brenda Steurer), Dan Wegmueller and Mojito the Brown Swiss (Noreen Rueckert), Kayak on the Sugar River (Brenda Steurer), Swiss Cheese (Bill Wyss), Beer and Cheese (Wisconsin Milk Marketing Board), 100 Accordions Player at the 2014 Cheese Days Festival (Brenda Steurer), 2014 Green County Dairy Queen Kelsey Cramer with Sarah the Cheese Lady (Gary Knowles). This page and opposite: “Field of Happiness”– Sunflowers near Albany (Brenda Steurer), Bikes on the Sugar River Trail (Noreen Rueckert), Alphorn Players (Brenda Steurer), 2015 Green County Fairest of the Fair Whitney Disch (Brenda Steurer), Concerts on the Square (Noreen Rueckert). -

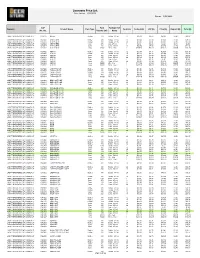

Licensees Price List Price List for 1/20/2020 Ran on 1/13/2020

Licensees Price List Price List for 1/20/2020 Ran on 1/13/2020 SAP Pack Package Full Brewery Product Name Pack Type Pack Size Content ($) HST ($) Price ($) Deposit ($) Total ($) Art. No. Volume (ml) Name LABATT BREWERIES OF CANADA LP 1024125 BLEUE Bottles 710 Bottles 710 ml 12 $38.91 $5.06 $43.97 $2.40 $46.37 LABATT BREWERIES OF CANADA LP 1025002 KEITHS RED Bottles 341 Bottles 341 ml 12 $23.00 $2.99 $25.99 $1.20 $27.19 LABATT BREWERIES OF CANADA LP 1025005 KEITHS RED Bottles 341 Bottles 341 ml 24 $43.36 $5.64 $49.00 $2.40 $51.40 LABATT BREWERIES OF CANADA LP 1025004 KEITHS RED Can 473 Can 473 ml 1 $2.14 $0.28 $2.42 $0.10 $2.52 LABATT BREWERIES OF CANADA LP 1025041 KEITHS RED Cans 473 Cans 473 ml 24 $60.80 $7.90 $68.70 $2.40 $71.10 LABATT BREWERIES OF CANADA LP 1025027 KEITHS RED Keg 58600 58.6 L Keg 1 $280.49 $36.46 $316.95 $50.00 $366.95 LABATT BREWERIES OF CANADA LP 1026002 KEITHS Bottles 341 Bottles 341 ml 12 $24.07 $3.13 $27.20 $1.20 $28.40 LABATT BREWERIES OF CANADA LP 1026005 KEITHS Bottles 341 Bottles 341 ml 24 $45.13 $5.87 $51.00 $2.40 $53.40 LABATT BREWERIES OF CANADA LP 1026031 KEITHS Cans 355 Cans 355 ml 12 $24.61 $3.20 $27.81 $1.20 $29.01 LABATT BREWERIES OF CANADA LP 1026033 KEITHS Cans 355 Cans 355 ml 24 $47.21 $6.14 $53.35 $2.40 $55.75 LABATT BREWERIES OF CANADA LP 1026004 KEITHS Can 473 Can 473 ml 1 $2.48 $0.32 $2.80 $0.10 $2.90 LABATT BREWERIES OF CANADA LP 1026041 KEITHS Cans 473 Cans 473 ml 24 $60.80 $7.90 $68.70 $2.40 $71.10 LABATT BREWERIES OF CANADA LP 1026091 KEITHS Keg 20000 20 L Keg 1 $111.02 $14.43 $125.45 $20.00 -

Crc - Liquor List

2701 W Howard Street Chicago, IL 60645-1303 PH: 773.465.3900 Fax: 773.465.6632 Rabbi Sholem Fishbane Kashruth Administrator Items listed as "Recommended" do not require a kosher symbol unless they are marked with a star (*) Due to continual changes in the liquor industry, alcoholic beverages which are certified as kosher are preferable to those which are merely "Recommended" This list is updated regularly and should be considered accurate until December 31, 2014 cRc - Liquor List Bar Stock Items Bar Stock Items Bar equipment (strainers, shot measures, blenders, stir Other rods, shakers, etc.) used with non-kosher products Cream of Coconut should be properly cleaned and/or kashered prior to use Requires Certification with kosher products. Lemon Slices must be prepared using a kosher knife and on a Recommended kosher cutting board Coco Lopez OU* Limes Assorted Varieties Slices must be prepared using a kosher knife and on a Daily's OU* kosher cutting board Assorted Varieties Maraschino Cherries Jamaica John cRc* Require Certification Jero OK* Olives - Black, Domestic Rose's - Cocktail Infusion Blue OU* Recommended if packed in water with no added flavors or colors Raspberry Olives - Green Rose's - Cocktail Infusion Cranberry OU* Require Certification Twist Onions - Pearl Rose's - Cocktail Infusion Sour Apple OU* Canned or jarred require certification Rose's - Grenadine OU* Rose's - Mojito Mango OU* Beer Rose's - Mojito Passion Fruit OU* All unflavored beers with no additives are acceptable, OU* Rose's - Mojito Traditional even without Kosher certification. This applies to both Rose's - Sweet & Sour (Ready to Use) OU* American and imported beers, light, dark and non- Rose's - Sweetened Lime Juice OU* alcoholic beers. -

Activity Packet Guide Planning Time!

ACTIVITY PACKET GUIDE PLANNING TIME! On behalf of the POCI Executive Committee and Board of Directors, I would like to thank you for registering for the 46th annual Pontiac Oakland Club International Convention. We are pleased to welcome you to the Wisconsin Dells. This year’s host hotel is the Chula Vista Resort, which includes a golf course and water park. The Convention Committee, Art Barrett and Larry Crider, have been busy working with the host Chapters - the God’s Country Chapter and the Badger Chapter of POCI - and the local coordinator Joe Morgan, to plan many fun activities. While making your plans to attend the Convention, I hope you take some time to visit the local attractions. Be sure to visit the model car and coloring contests, the Chapter displays, the Road Warrior, Popular Vote, and Points-Judged Car Shows. Also, visit the guest speaker seminars and Specialty Chapter Meetings. Don’t forget the Oakland Breakfast cruise, Road Warrior lunch cruise, and many other activities. Looking for a part to complete your Pon- tiac, Oakland, or GMC? Try the Swap meet and Vendor area. The POCI welcome night, sponsored by Ames Performance, is open to all, and is always a fun time. Don’t forget to attend the POCI Chapter Night Banquet, and the final activity, the Car Show Awards Banquet. All should prove to be outstanding entertainment. Thank you for planning your vacation with us! Wayne Beran, POCI President Version 1: 2/15/18 Page 2 WHAT’S INSIDE... Your POCI Convention Planning Guide! Who to contact for Letter from POCI Pres. -

Certificate of Compliance (Suppliers) Report As of April 22, 2014 1015927343 101 NORTH BREWING CO 1304 SCOTT ST STE D PETALUMA C

Certificate of Compliance (Suppliers) Report as of April 22, 2014 1015927343 101 NORTH BREWING CO 1304 SCOTT ST STE D PETALUMA CA 949547100 7077788384 1015170773 1010 INTERNATIONAL 4409 W 25TH PL LAWRENCE KS 660479673 9137356055 1006638431 13 APPELLATIONS LLC 4006 SILVERADO TRL NAPA CA 945581124 7072581454 1008570087 21ST AMENDMENT BREWERY 563 2ND ST SAN FRANCISCO CA 941071411 4158060900 1006562982 21ST CENTURY SPIRITS LLC 6560 E WASHINGTON BLVD LOS ANGELES CA 900401822 1016418833 220 IMPORTS LLC 3792 E COVEY LN PHOENIX AZ 850505002 6024020537 1006327703 24/7 IMPORTS 2580 ANTHEM VILLAGE DR HENDERSON NV 890525503 7025885323 1016333536 3 CROWNS DISTRIBUTORS 950 MOUNTAIN VEW AVE OXNARD CA 93030 8057972127 1016283920 312 SPIRITS LLC 980 N MICHIGAN AVE STE 1800 CHICAGO IL 606117538 3122550064 1016640382 4 FOXES 509 MATHESON ST HEALDSBURG CA 954484215 7074317425 1002694680 7CS WINERY LLC 502 E 560TH RD WALNUT GROVE MO 657708394 4177882263 1014665400 8 VINI INC 30911 WIEGMAN CT HAYWARD CA 945447809 5106758888 1014476771 88 SPIRITS CORP 1701 S GROVE AVE STE D ONTARIO CA 917614500 9097861071 1015273823 90+ CELLARS 14100 MOUNTAIN HOUSE RD HOPLAND CA 954499782 8558798466 1012016137 A LA VIDA WINES & SPIRITS LLC 1531 CORONA HILL CT LAS VEGAS NV 891235877 7022708517 1008735540 A P VIN 622 TREAT AVE SAN FRANCISCO CA 941102016 4152852773 1006578404 A RAFANELLI WINERY 4685 W DRY CREEK RD HEALDSBURG CA 954488124 7074331385 1006641998 A TO Z/REX HILL/FRANCIS TANNAHILL/ WM HATCHER 30835 N HIGHWAY 99W NEWBERG OR 971326966 5035541918 1016797648 AARON J WALUDA -

August 2017 Legal & Legislative Update

August 2017 Legal & Legislative Update A. FEDERAL / NATIONAL / INTERNATIONAL Craft Beverage Modernization and Tax Reform Act The Craft Beverage Modernization and Tax Reform Act (S.236/H.R.747) was reintroduced in both chambers of the 115th Congress. Sponsors total 47 in the U.S. Senate and 253 in the U.S. House of Representatives. Specific tax provisions of the bill include: reducing the federal excise tax to $3.50 per barrel on the first 60,000 barrels for domestic brewers producing fewer than 2 million barrels annually; reducing the federal excise tax to $16 per barrel on the first 6 million barrels for all other brewers and all beer importers; keeping the excise tax at the current $18 per barrel rate for barrelage over 6 million. The Craft Modernization and Tax Reform Act would also ease a number of burdens for brewers, including simplifying label approvals and repealing unnecessary inventory restrictions. Brewers Association Submits Further Comments on Menu Labeling The Brewers Association submitted comments to the Food and Drug Administration focused on non-menu options for making calorie and nutrient data available, emphasizing the widespread availability of smart phones since the time the requirement was promulgated and the benefits for retailers in being able to provide current information in a timely manner. B. THE COURTS AB-InBev and Molson Coors Sued for Restraint of Trade Plaintiff Mountain Crest SRL, LLC, owners of Minhas Craft Brewery in Monroe, WI, has brought suit in U.S. District Court against Anheuser-Busch InBev and Molson Coors Brewing Co. alleging those companies conspired to restrain plaintiff’s and others export trade to the Province of Ontario, Canada. -

Finding Community at the Bottom of a Pint Glass: an Assessment of Microbreweries' Impacts on Local Communities a Research Pape

FINDING COMMUNITY AT THE BOTTOM OF A PINT GLASS: AN ASSESSMENT OF MICROBREWERIES‘ IMPACTS ON LOCAL COMMUNITIES A RESEARCH PAPER SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTERS OF URBAN AND REGIONAL PLANNING BY MAXWELL DILLIVAN DR. BRUCE FRANKEL – ADVISOR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA MAY 2012 Table of Contents Table of Figures ................................................................................................................. iii Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................. iv I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Literature Review ........................................................................................................... 4 History and Significance of Beer and Microbreweries ................................................... 4 Economic Impacts ........................................................................................................... 9 Cultural Identity and Localism ..................................................................................... 12 Sense of Place ............................................................................................................... 16 Sense of Community ...................................................................................................... 22 Third Place................................................................................................................... -

Offered by Transwestern Exclusive Listing Agent

OFFERED BY TRANSWESTERN EXCLUSIVE LISTING AGENT MARIANNE BURISH, MBA Executive Vice President D 414.270.4132 C 414.520.2576 E [email protected] JOHN DULMES Executive Vice President D 414.270.4109 C 414.305.3070 E [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS OFFERING SUMMARY PROPERTY SPECIFICATIONS PROPERTY DATA − About the Property − Location Map − Floor Plan − 2016 Survey − Property Aerial View − Parcel Report − Real Estate Tax Bill − Property Photos − Retailer Trade Area − Area Amenities LOCATION OVERVIEW − Drive Time Analysis − Public Transportation − Milwaukee Overview − Demographics − Key Facts 5055 NORTH LYDELL AVENUE | 2 OFOFFERINGFERING SUMM SUMMARYARY The Offering Transwestern, on behalf of owner, is offering for sale a 100% fee simple interest in the Lydell Corporate Center located at 5055 North Lydell Avenue in progressive Glendale, Wisconsin. Built in 1956 and renovated in 2002, this affordable office property on over 15 acres is a rare large parcel ready for your redevelopment vision, new tenants/owner-occupants, or both. Located in the Milwaukee MSAs highly desired Northshore area, the Property is a quick drive from downtown and steps from bustling retail and attractive residential neighborhoods. Target Audience Redevelopment; full or partial owner-occupancy or re-tenant/investment Building Name & Lydell Corporate Center Property Address 5001-5055 North Lydell Avenue, Glendale, WI 53217 Property Parcel Size 15.55 acres per 2016 survey; 14.40 acres per municipal data Building Size +-277,000 GSF (+-217,000 -

Washington, DC

THE ROUTE Legislative Conference Issue • April 2019 Message from Chairman of the NBWA Board Michael Schilleci and NBWA President and CEO Craig Purser Welcome to Washington, D.C. e are excited to have you here in Washington, D.C. for NBWA’s 2019 Legislative Conference! W This year’s conference features an exciting lineup of new speakers, new networking opportunities and industry receptions. Together, we’ll spend the next few days educating lawmakers about the value of the independent beer distribution system as we support policies that encourage choice, innovation and growth. Earlier this year, the U.S. House of Representatives and the Senate swore-in more than 100 new members of Congress, and they’re waiting to hear from you! We are excited to share with lawmakers how distrib- utors are delivering more than 141,000 local jobs — with benefits and room for advancement — in every congressional district. And, as lawmakers consider hot-button issues like tax reform, jobs, marijuana legalization and the expansion of e-commerce, it’s more important than ever for beer distributors to be top of mind as they cast their votes. In addition to meeting with members of Congress during this Legislative Conference, we’ll also get an update about the judicial branch. As you know, the Supreme Court of the United States is considering a case involving alcohol regulation that could impact our industry. Distributor members will hear directly from the legal experts working on the case, Tennessee Wine & Spirits Retailers Association v. Thomas, as they share their latest insights. But don’t worry – it won’t be all work.