Multicultural Education in Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cross-Regional Perinatal Healthcare Systems: Efforts in Greater Kansai Area, Japan

Conferences and Lectures Cross-Regional Perinatal Healthcare Systems: Efforts in Greater Kansai Area, Japan JMAJ 53(2): 86–90, 2010 1 Noriyuki SUEHARA* Fukui Kyoto Shiga Introduction Hyogo Aiming to create a society in which any woman can give birth without any sense of anxiety, Japan’s Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare Osaka Mie (MHLW) has been promoting the establishment Nara and systemization of general perinatal medical Tokushima centers nationwide since 1996. Wakayama In Osaka Prefecture, Neonatal Mutual Coop- erative System (NMCS) was established in 1977, and then Obstetric & Gynecologic Cooperative System (OGCS) in 1978. This illustrates that sys- 100km temization of perinatal healthcare is in progress in Osaka. Under OGCS, six hospitals (namely Osaka Medical Center and Research Institute for Maternal and Child Health, Osaka City General Hospital, Takatsuki General Hospital, Aizenbashi Hospital, Kansai Medical University Hirakata Hospital, and Yodogawa Christian Hospital) are designated as Base Hospitals, plus, nine other facilities are designated as Sub-base Hospitals. These hospitals play a large role in the Osaka’s regional perinatal healthcare system. In 1999, Osaka Council on Perinatal Health- Tokyo care Strategies was established, and in December of that year Osaka Medical Center and Research 500 km Institute for Maternal and Child Health was des- ignated as the general perinatal medical center for Osaka Prefecture. Subsequently, four addi- fectural Government formulated Guideline for tional hospitals (Takatsuki General Hospital, Improving the Perinatal Emergency Medical Aizenbashi Hospital, Kansai Medical University System, and 13 regional perinatal medical centers Hirakata Hospital, and Osaka University Hospi- were approved. Furthermore, Osaka Prefecture tal) were designated as general perinatal medical Guidelines for Prioritizing Perinatal Healthcare centers, serving as core facilities for perinatal Functions were drawn up in December 2008 based healthcare system in Osaka. -

The Politics of Constructing National Identity and Mandatory Detention of Asylum-Seekers in Australia and Japan

National Identity Crisis: The Politics of Constructing National Identity and Mandatory Detention of Asylum-Seekers in Australia and Japan Emily Flahive I. Introduction II. International and Domestic Law on Detention Part A – International Law Part B – Australia’s Laws on Mandatory Detention Part C – Japan’s Laws on Mandatory Detention III. National Identity Part A – Theory of National Identity Part B – Japan’s National Identity in its Immigration and Citizenship Laws Part C – Australia’s National Identity in its Immigration and Citizenship Laws IV. National Identity Crisis V. Conclusion I. INTRODUCTION In an era marked by increasingly repressive policies regarding asylum-seekers, 2005 witnessed two seemingly unconnected countries – Australia and Japan – soften their laws on the detention of unlawful asylum-seekers. 1 Japan and Australia, however, are not so different: in response to the perceived threat to their national identities both countries have developed policies of mandatory detention for unlawful asylum-seekers. Through the use of immigration and citizenship laws, the Australian and Japanese governments have excluded asylum-seekers as the nations’ ‘other’, thereby justifying their detention. In examining how ostensibly different examples as Australia and Japan have developed similar refugee policies, universal elements of national identity emerge that can be used by refugee advocates worldwide. Japan and Australia have undertaken an international obligation not to punish refugees for arriving unlawfully in their countries. 2 Under international law, the deten- tion of an asylum-seeker is not considered punishment if such detention is deemed ‘necessary’ by the host state. 3 In its recommended guidelines, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees sets out when, in its view, detention might be considered 1 In this article, the term ‘unlawful asylum-seeker’ denotes an asylum-seeker who has entered a country without a valid visa or passport. -

Essentials for Living in Osaka (English)

~Guidebook for Foreign Residents~ Essentials for Living in Osaka (English) Osaka Foundation of International Exchange October 2018 Revised Edition Essentials for Living in Osaka Table of Contents Index by Category ⅠEmergency Measures ・・・1 1. Emergency Telephone Numbers 2. In Case of Emergency (Fire, Sudden Sickness and Crime) Fire; Sudden Illness & Injury etc.; Crime Victim, Phoning for Assistance; Body Parts 3. Precautions against Natural Disasters Typhoons, Earthquakes, Collecting Information on Natural Disasters; Evacuation Areas ⅡHealth and Medical Care ・・・8 1. Medical Care (Use of medical institutions) Medical Care in Japan; Medical Institutions; Hospital Admission; Hospitals with Foreign Language Speaking Staff; Injury or Sickness at Night or during Holidays 2. Medical Insurance (National Health Insurance, Nursing Care Insurance and others) Medical Insurance in Japan; National Health Insurance; Latter-Stage Elderly Healthcare Insurance System; Nursing Care Insurance (Kaigo Hoken) 3. Health Management Public Health Center (Hokenjo); Municipal Medical Health Center (Medical Care and Health) Ⅲ Daily Life and Housing ・・・16 1. Looking for Housing Applying for Prefectural Housing; Other Public Housing; Looking for Private Housing 2. Moving Out and Leaving Japan Procedures at Your Old Residence Before Moving; After Moving into a New Residence; When You Leave Japan 3. Water Service Application; Water Rates; Points of Concern in Winter 4. Electricity Electricity in Japan; Application for Electrical Service; Payment; Notice of the Amount of Electricity Used 5. Gas Types of Gas; Gas Leakage; Gas Usage Notice and Payment Receipt 6. Garbage Garbage Disposal; How to Dispose of Other Types of Garbage 7. Daily Life Manners for Living in Japan; Consumer Affairs 8. When You Face Problems in Life Ⅳ Residency Management System・Basic Resident Registration System for Foreign Nationals・Marriage・Divorce ・・・27 1. -

2009 Outbreak and School Closure, Osaka Prefecture, Japan

LETTERS Influenza (H1N1) 2009 virus was spreading widely to each school’s administrator. The pre- other schools and communities and fecture-wide school closure strategy 2009 Outbreak and that school closures would be neces- may have had an effect on not only the School Closure, sary (1,2). reduction of virus transmission and Osaka Prefecture, The governor of Osaka decided elimination of successive large out- to close all 270 high schools and 526 breaks but also greater public aware- Japan junior high schools in Osaka Prefec- ness about the need for preventive To the Editor: The Osaka Prefec- ture from Monday, May 18, to Sunday, measures. tural Government, the third largest lo- May 24, following the weekend days cal authority in Japan and comprising of May 16 and 17 observed at most Acknowledgments 43 cities (total population 8.8 million), schools. Students were ordered to stay We thank the public health centers in was informed of a novel influenza out- at home (3). Most nurseries, primary Osaka, Sakai, Higashiosaka, and Takatsuki break on May 16, 2009. A high school schools, colleges, and universities for data collection and the National Insti- submitted an urgent report that ≈100 in the 9 cities with influenza cases tute of Infectious Disease, Tokyo, for help- students had influenza symptoms; voluntarily followed the governor’s ful advice. an independent report indicated that decision. Antiviral drugs were pre- scribed by local physicians to almost a primary school child also showed Ryosuke Kawaguchi, all students with confirmed infection; similar symptoms. Masaya Miyazono, families were given these drugs as a The Infection Control Law in Ja- Tetsuro Noda, prophylactic measure. -

European Respiratory Society Annual Congress 2013 Abstract Number: 693 Publication Number: P1393 Abstract Group: 12.3

European Respiratory Society Annual Congress 2013 Abstract Number: 693 Publication Number: P1393 Abstract Group: 12.3. Genetics and Genomics Keyword 1: Genetics Keyword 2: No keyword Keyword 3: No keyword Title: Association between ADAM33 polymorphisms and asthma control Dr. Guergana 8012 Petrova [email protected] MD 1,2, Dr. Hisako 8017 Matsumoto [email protected] MD 1, Dr. Yoshihiro 8018 Kanemitsu [email protected] MD 1, Dr. Kenji 8019 Izuhara [email protected] MD 3, Dr. Yuji 8020 Tohda [email protected] MD 4, Dr. Hideo 8026 Kita [email protected] MD 5, Dr. Takahiko 8028 Horiguchi [email protected] MD 6, Dr. Kazunobu 8030 Kuwabara [email protected] MD 6, Dr. Keisuke 8031 Tomii [email protected] MD 7, Dr. Kojiro 8032 Otsuka [email protected] MD 1,7, Dr. Masaki 8033 Fujimura [email protected] MD 8, Dr. Noriyuki 8034 Ohkura [email protected] MD 9, Dr. Katsuyuki 8035 Tomita [email protected] MD 4, Dr. Akihito 8036 Yokoyama [email protected] MD 9, Dr. Hiroshi 8037 Ohnishi [email protected] MD 9, Dr. Yasutaka 8038 Nakano [email protected] MD 10, Dr. Tetsuya 8039 Oguma [email protected] MD 10, Dr. Soichiro 8040 Hozaqa [email protected] MD 11, Dr. Tadao 8041 Nagasaki [email protected] MD 1, Dr. Isao 8042 Ito [email protected] MD 1, Dr. -

Latin American Critical Thought Latin American Critical Thought: Theory and Practice / Compilado Por Alberto L

Jorge Arzate Salgado Este libro contiene una serie de trabajos que desdoblan el sentido Latin American Jorge Arzate Salgado de la pobreza como carencia, es decir, presentan las situaciones Doctor en Sociología (Universidad de Salamanca). Doctor en Sociología (Universidad de Salamanca). de pobreza en tanto que formas de vida. Para la tarea se acude al Docente e investigador en la Facultad de Ciencias Docente e investigador en la Facultad de Ciencias uso de categorías sociológicas como la de clase, género, espacio Critical Thought Políticas y Sociales de la Universidad Autónoma del Políticas y Sociales de la Universidad Autónoma del regional, etnia, estructura social. Cada texto presenta una versión Estado de México. Miembro del Sistema Nacional de Estado de México. Miembro del Sistema Nacional de crítica de lo que es la reproducción de la pobreza, por lo que ésta Investigadores. Ha publicado más de cincuenta Investigadores. Ha publicado más de cincuenta es descentrada de su orden estadístico y es colocada como Theory and Practice trabajos académicos y ha sido conferencista en trabajos académicos y ha sido conferencista en referencia a un sistema de relaciones sociales y económicas diversos países de Iberoamérica. diversos países de Iberoamérica. situadas históricamente. Los actores aparecen no sólo como reproductores pasivos de las situaciones de carencia, sino Alicia B. Gutiérrez Alicia B. Gutiérrez como sujetos activos que construyen su tiempo vital, sus Doctora en Sociología (EHSS) y Doctora en Antropología instituciones sociales y económicas, -

On the Issue of Origin of the Yakut Epic Olonkho

Journal of History Culture and Art Research (ISSN: 2147-0626) Tarih Kültür ve Sanat Araştırmaları Dergisi Vol. 7, No. 1, March 2018 Revue des Recherches en Histoire Culture et Art Copyright © Karabuk University http://kutaksam.karabuk.edu.tr ﻣﺠﻠﺔ اﻟﺒﺤﻮث اﻟﺘﺎرﯾﺨﯿﺔ واﻟﺜﻘﺎﻓﯿﺔ واﻟﻔﻨﯿﺔ DOI: 10.7596/taksad.v7i1.1369 Citation: Ivanov, V., Koriakina, A., Savvinova, G., & Anisimov, R. (2018). On the Issue of Origin of the Yakut Epic Olonkho. Journal of History Culture and Art Research, 7(1), 194-204. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.7596/taksad.v7i1.1369 On the Issue of Origin of the Yakut Epic Olonkho Vasiliy Nikolayevich Ivanov1, Antonina Fedorovna Koriakina2, Gulnara Egorovna Savvinova3, Ruslan Nikolayevich Anisimov4 Abstract The issue on the origin of the Yakut heroic epic Olonkho was covered in works in history and ethnography of the Yakuts back in the 19th century, for instance, in the famous monograph Yakuts. Experience of ethnographic research by a Polish exile V.L. Seroshevskiy (1896). Since that time, this issue was interesting for many, but no special monograph research has been done yet. Currently, the issue of Olonkho origin is gaining special scientific and general cultural significance, as on November 25, 2005 the Yakut heroic epic Olonkho according to the historical decision of UNESCO was granted the high status “Masterpiece of oral and non-material heritage of humanity”. The Yakut epic is a part of the multicomponent epic creative work of the Turkic nations but it was the only one to get such a high international recognition. This paper aims to revive the scientific interest to the issue of the Yakut epic’s genesis. -

Goodman Takatsuki

Completion | Mid 2022 Goodman Takatsuki OVERVIEW+ ++ Located inland of Osaka, along Osaka Prefectural road 16 in the Hokusetsu area ++ A modern 4-story logistics facility with a leased area of approximately 6,600 tsubo ++ The surrounding area is densely populated and well-located for employment Driving distance Within 60 minutes driving distance Within 60 minutes Within 30 minutes Kyoto Kyoto Station Nagaokakyo Hyogo Takatsuki + Ibaraki PLANS Goodman Takatsuki Takarazuka Toyonaka Hirakata Amagasaki Nara Osaka StationOsaka A B A Higashi-Osaka Kobe Nara Port Kobe Osaka Airport Port source:Esri and Michael Bauer Research Floor 2/3 Floor 4 LOCATION+ ++ About 2 km from the JR Takatsuki Station and the Hankyu Takatsukishi Station Gross lettable area ( tsubo) ++ A bus stop is located nearby within walking distance Warehouse+ Piloti + About 5.6km from Takatsuki Interchange of Shin-Meishin Expressway, 8km from Ibaraki Interchange of Meishin Floor Office Total + berths driveway Expressway and 8km from Settsu-Kita Interchange of Kinki Expressway 4F A 620 − 40 660 ++ Good access to the Meishin and Shin-Meishin Expressways as well as to the Osaka CBD and Hokusetsu area B 1,275 − 5 1,280 3F A 605 − 130 735 hin-Meishin Expressway 2 km B 1,275 − 5 1,280 2F Takatsuki from JR Takatsuki A B A 605 − 130 735 JCT tation ankyu IC Takatsukishi B 1,050 220 10 1,280 JR Kyoto Line tation 1F Takatsuki A 420 180 50 650 Meishin B 3,600 220 20 3,840 Expressway Hankyu Kyoto Line Total Takatsukishi 5.6 km A 2,250 180 350 2,780 171 from Takatsuki IC Shin-Meishin Expy -

The Effects of Stigmatization, Group Sentiment and Standardization Movements on the Future of the Kashubian Language

Prospects for an Endangered Language: The Effects of Stigmatization, Group Sentiment and Standardization Movements on the Future of the Kashubian Language Patricia S. Vandel A Senior Essay in Linguistics Presented on May 6, 2004 Yale University New Haven, CT BA, Linguistics Berkeley College Advisor: Darya Kavitskaya Department ofLinguistics TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction 3 1.1 Overview ofthe Kashubian Language .4 1.2 Influence ofPolitical Climate on the Study ofKashubian 5 1.3 Linguistic History ofKashubia 6 1.4 Literature 7 1.5 Press and Media 8 1.6 Religion 9 1.7 Education 9 2.0 Use ofthe Kashubian Language 11 2.1 Language versus Dialect ~ .11 2.2 Dialectal Variation within Kashubia 12 2.3 Differences between Kashubian and Polish 13 2.3.1 Phonological Differences 13 2.3.2 Lexical Differences 15 2.3.3 Register Differences 16 2.3.4 Prestige Differences 17 2.4 Cultural Differences 17 2.5 Diglossia 18 3.0 Group Sentiment Among the Kashubs 21 3.1 Ethnicity '" 21 3.1.1 Language as a Symbol ofEthnicity 23 3.1.2 Kashubian Ethnic Identity 24 3.2 Nationalism ; 25 3.2.1 Language and Nationalism 27 3.2.2 Kashubian National Identity and the Post-Communist Transformation 28 4.0 Language Standardization 32 4.1 Adopting a Standard Language 34 4.2 Kashubian Efforts at Standardization 36 4.3 Problems Associated with Standardization 38 5.0 The Future ofKashubian 40 5.1 Efforts to Sustain Language Awareness ; 40 5.2 Language Shift 41 5.3 Why Are Speakers Abandoning the Kashubian Language? 45 6.0 Conclusion •................................................................................ -

Summary of Family Membership and Gender by Club MBR0018 As of June, 2009

Summary of Family Membership and Gender by Club MBR0018 as of June, 2009 Club Fam. Unit Fam. Unit Club Ttl. Club Ttl. District Number Club Name HH's 1/2 Dues Females Male TOTAL District 335 B 23732 ARIDA 0 0 0 48 48 District 335 B 23733 DAITO 0 0 0 46 46 District 335 B 23734 FUJIIDERA 0 0 0 26 26 District 335 B 23735 HIGASHI OSAKA FUSE 0 0 3 30 33 District 335 B 23736 HIGASHI OSAKA CHUO 0 0 0 21 21 District 335 B 23737 HIGASHI OSAKA KIKUSUI 0 0 0 38 38 District 335 B 23738 GOBO 0 0 0 51 51 District 335 B 23739 HABIKINO 0 0 0 42 42 District 335 B 23740 HASHIMOTO 0 0 0 32 32 District 335 B 23741 HIGASHI OSAKA APOLLO 0 0 0 20 20 District 335 B 23742 HIRAKATA 0 0 0 73 73 District 335 B 23743 HIGASHI OSAKA 0 0 1 38 39 District 335 B 23744 IBARAKI 0 0 0 92 92 District 335 B 23745 IKEDA 0 0 0 55 55 District 335 B 23746 ITO KOYASAN L C 0 0 0 32 32 District 335 B 23747 IZUMIOSAKA 0 0 0 27 27 District 335 B 23748 IZUMI OTSU 0 0 0 69 69 District 335 B 23749 IZUMISANO 0 0 0 26 26 District 335 B 23750 IZUMISANO CHUO 0 0 0 35 35 District 335 B 23751 KADOMA 0 0 0 20 20 District 335 B 23752 KAINAN 0 0 0 30 30 District 335 B 23753 KAIZUKA 0 0 0 34 34 District 335 B 23754 KAWACHINAGANO 1 0 2 34 36 District 335 B 23755 HIGASHI OSAKA KAWACHI 0 0 2 25 27 District 335 B 23756 KASHIWARA 0 0 0 68 68 District 335 B 23758 KATSUURA 0 0 0 23 23 District 335 B 23759 KISHIWADA CHIKIRI 0 0 0 44 44 District 335 B 23760 KISHIWADA 0 0 0 45 45 District 335 B 23761 KISHIWADA CHUO 0 0 2 55 57 District 335 B 23763 KONGO 1 1 0 28 28 District 335 B 23764 KUSHIMOTO 0 0 2 24 -

IX-3 Health and Medical Care

IX-3 Health and Medical Care 1. Emergency Medical Clinics (Service available only in Japanese. It is recommended that you bring along someone competent in Japanese.) Int Internal Ped Pediatrics Medicine Sur General Den Dentistry Surgery Oph Ophthalmology Oto Otolaryngology Ort Orthopedics ※ You can find more information using Osaka Medical Facilities Information System search enging. (https://www.mfis.pref.osaka.jp/apqq/qq/men/pwtpmenult01.aspx) Town Facility Name Address Tel Reception Hours Suita Municipal 19-2 Deguchi-cho, Sun, Holidays, Year-end Suita Emergency Clinic Suita 06-6339-2271 & New Year Int Ped Sur Den 9:30-11:30, 13:00-16:30 Weeknights (Int・Ped・Sur)20:30-6:30 Osaka Mishima Sat (Int・Ped・Sur) Emergency 14:30-6:30 11-1 Medical Center/ Sun and Holidays Minami-akutagawa Shimamoto & Takatsuki 072-683-9999 cho, Takatsuki (Int・Ped・Sur) Takatsuki Shimamoto 9:30-11:30, 13:30-16:30, Emergency Clinic 18:30-6:30 Int Ped Sur Den Sun and Holidays (Den) 9:30-11:30, 13:30-16:30 Weeknights Ibaraki Municipal (Int) 21:00-23:30 Public Health and Sat (Int) 17:00-6:30 Medical Center Emergency Clinic Sun and Holidays 3-13-5 Kasuga, Ibaraki Int. Den 072-625-7799 (Int) Ibaraki 10:00-11:30, 13:00-16:30, *For pediatrics, 18:00-6:30 visit Takatsuki/ Sun and Holidays Shimamoto Emergency Clinic (Den) 10:00-11:30, 13:00-16:30 Settsu Municipal Sun, Holidays, Year-end Emergency 32-19 Kohroen, Settsu 072-633-1171 & New Year Pediatric Clinic Settsu Ped 10:00-11:30, 13:30-16:30 Clinic of Toyonaka Sun, Holidays, Aug 14/15, Municipal Health 2-6-1 Uenosaka, 06-6848-1661 -

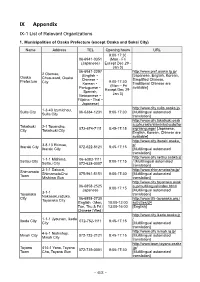

IX Appendix IX-1 List of Relevant Organizations

IX Appendix IX-1 List of Relevant Organizations 1. Municipalities of Osaka Prefecture (except Osaka and Sakai City) Name Address TEL Opening hours URL 9:00-17:30 06-6941-0351 (Mon - Fri (Japanese) Except Dec 29 - Jan 3) 06-6941-2297 http://www.pref.osaka.lg.jp/ 2 Otemae, (English・ [Japanese, English, Korean, Osaka Chuo-ward, Osaka Chinese・ Simplified Chinese, Prefecture 9:00-17:30 City Korean・ Traditional Chinese are (Mon – Fri Portuguese・ available] Except Dec 29- Spanish, Jan 3) Vietnamese・ Filipino・Thai・ Japanese) http://www.city.suita.osaka.jp/ 1-3-40 Izumichou, Suita City 06-6384-1231 9:00-17:30 [Multilingual automated Suita City translation] http://www.city.takatsuki.osak a.jp/kurashi/shiminkatsudo/for Takatsuki 2-1 Touencho, 072-674-7111 8:45-17:15 eignlanguage/ [Japanese, City Takatsuki City English, Korean, Chinese are available] http://www.city.ibaraki.osaka.j 3-8-13 Ekimae, p/ Ibaraki City 072-622-8121 8:45-17:15 Ibaraki City [Multilingual automated translation] http://www.city.settsu.osaka.jp 1-1-1 Mishima, 06-6383-1111 Settsu City 9:00-17:15 / [Multilingual automated Settsu City 072-638-0007 translation] 2-1-1 Sakurai, http://www.shimamotocho.jp/ Shimamoto ShimamotoCho 075-961-5151 9:00-17:30 [Multilingual automated Town Mishima Gun translation] http://www.city.toyonaka.osak 06-6858-2525 a.jp/multilingual/index.html/ 9:00-17:15 Japanese [Multilingual automated 3-1-1 Toyonaka translation] Nakasakurazuka, City 06-6858-2730 http://www.tifa-toyonaka.org./ Toyonaka City English(Mon, 10:00-12:00 activities/34 Tue, Thu & Fri) 13:00-16:00