FALL 2003 Public Reception, Politics, and Propaganda in Torrejón's Loa To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Présentation D'une Séquence – Formateurs Académiques

Présentation d’une séquence – Formateurs Académiques Formation Initiale, Académie de Versailles – août 2019 BMI - BB Titre de la séquence : “La música en la calle: ¿tradición popular o vector de cohesión social?” Programme culturel : L’art de vivre ensemble Axes : Axe 3 - Le village, le quartier, la ville (Axe 1 - Vivre entre générations / Axe 6 - La création et le rapport aux arts) Problématique : ¿En qué sentido podemos decir que la música y el baile, al manifestarse en la calle, son una afirmación de la identidad, y los vectores de la cohesión social de un pueblo ? Niveau : 2de Niveau du CECRL : A2 Nombre de séances : (½ séance d’introduction) + 4 séances + 1 séance pour l’évaluation (+ remédiation) • Objectifs culturels : -musiques et danses traditionnelles d’Espagne et d’A-L - Cuba, Argentine, Pérou (sevillana (et la feria de Séville), flamenco, tango, milonga, rumba, conga, marinera, huayno) -le réalisateur Fernando Trueba, le musicien et compositeur Bebo Valdés, l’écrivain José María Arguedas, le musicien Eliades Ochoa et le Buena Vista Social Club, le danseur de flamenco Eduardo Guerrero, la chanteuse Buika, le groupe Calle 13, le chanteur et musicien Manu Chao • Outils linguistiques : -lexicaux : le lexique lié aux danses étudiées et à la musique, quelques instruments de musique, le lexique lié à la cohésion sociale, à l’identité, au vivre ensemble, au partage, le lexique des sentiments tels que la joie, le lexique lié aux héritages, métissages, à la fusion des cultures, le lexique de la description d’images, des nationalités -

STATEWIDE APPRENTICESHIP PROGRAM SUPPORTS CALIFORNIA's CULTURAL TRADITIONS THROUGH 17 ARTIST TEAMS Since 1999, the Alliance Fo

STATEWIDE APPRENTICESHIP PROGRAM SUPPORTS CALIFORNIA’S CULTURAL TRADITIONS THROUGH 17 ARTIST TEAMS Since 1999, the Alliance for California Traditional Arts’ (ACTA’s) Apprenticeship Program has supported California’s cultural traditions with 348 contracts to outstanding folk and traditional artists and practitioners. Now entering its 19th cycle, ACTA’s Apprenticeship Program encourages the continuity of the state’s living cultural heritage by contracting exemplary master artists to offer intensive training and mentorship to qualified apprentices. ACTA’s Executive Director, Amy Kitchener says, “The Apprenticeship Program is at the heart of our mission, with a focus on the generational transfer of knowledge. The program not only sustains and grows traditions; it also reveals all the different ways of knowing within the many cultural communities of our state.” Master artist Snigdha Venkataramani (L) with her apprentice Anagaa Nathan (R; photo courtesy of Suri Photography). Contracts of $3,000 are made with California-based master artists to cover master artist’s fees, supplies and travel. Participants work closely with ACTA staff to develop and document the apprenticeships, culminating in opportunities to publicly share results of their work. The 2019 Apprenticeship Program cohort of 34 artists (17 pairs) reflects California’s breadth of cultural diversity and intergenerational learning, ranging from master artists in their 60s to a 15-year old apprentice, spanning from San Diego to Humboldt Counties. Thriving traditions supported through these apprenticeships reflect indigenous California cultural practices that include Yurok, Karuk, and Hupa basketry. Others celebrate traditions which have taken root in California, and originally hail from Peru, Africa, Bolivia, India, Iran, Armenia, China, Japan, Philippines, Korea, Mexico, and Vietnam. -

The Global Reach of the Fandango in Music, Song and Dance

The Global Reach of the Fandango in Music, Song and Dance The Global Reach of the Fandango in Music, Song and Dance: Spaniards, Indians, Africans and Gypsies Edited by K. Meira Goldberg and Antoni Pizà The Global Reach of the Fandango in Music, Song and Dance: Spaniards, Indians, Africans and Gypsies Edited by K. Meira Goldberg and Antoni Pizà This book first published 2016 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2016 by K. Meira Goldberg, Antoni Pizà and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-9963-1 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-9963-5 Proceedings from the international conference organized and held at THE FOUNDATION FOR IBERIAN MUSIC, The Graduate Center, The City University of New York, on April 17 and 18, 2015 This volume is a revised and translated edition of bilingual conference proceedings published by the Junta de Andalucía, Consejería de Cultura: Centro de Documentación Musical de Andalucía, Música Oral del Sur, vol. 12 (2015). The bilingual proceedings may be accessed here: http://www.centrodedocumentacionmusicaldeandalucia.es/opencms/do cumentacion/revistas/revistas-mos/musica-oral-del-sur-n12.html Frontispiece images: David Durán Barrera, of the group Los Jilguerillos del Huerto, Huetamo, (Michoacán), June 11, 2011. -

7'Tie;T;E ~;&H ~ T,#T1tmftllsieotog

7'tie;T;e ~;&H ~ t,#t1tMftllSieotOg, UCLA VOLUME 3 1986 EDITORIAL BOARD Mark E. Forry Anne Rasmussen Daniel Atesh Sonneborn Jane Sugarman Elizabeth Tolbert The Pacific Review of Ethnomusicology is an annual publication of the UCLA Ethnomusicology Students Association and is funded in part by the UCLA Graduate Student Association. Single issues are available for $6.00 (individuals) or $8.00 (institutions). Please address correspondence to: Pacific Review of Ethnomusicology Department of Music Schoenberg Hall University of California Los Angeles, CA 90024 USA Standing orders and agencies receive a 20% discount. Subscribers residing outside the U.S.A., Canada, and Mexico, please add $2.00 per order. Orders are payable in US dollars. Copyright © 1986 by the Regents of the University of California VOLUME 3 1986 CONTENTS Articles Ethnomusicologists Vis-a-Vis the Fallacies of Contemporary Musical Life ........................................ Stephen Blum 1 Responses to Blum................. ....................................... 20 The Construction, Technique, and Image of the Central Javanese Rebab in Relation to its Role in the Gamelan ... ................... Colin Quigley 42 Research Models in Ethnomusicology Applied to the RadifPhenomenon in Iranian Classical Music........................ Hafez Modir 63 New Theory for Traditional Music in Banyumas, West Central Java ......... R. Anderson Sutton 79 An Ethnomusicological Index to The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, Part Two ............ Kenneth Culley 102 Review Irene V. Jackson. More Than Drumming: Essays on African and Afro-Latin American Music and Musicians ....................... Norman Weinstein 126 Briefly Noted Echology ..................................................................... 129 Contributors to this Issue From the Editors The third issue of the Pacific Review of Ethnomusicology continues the tradition of representing the diversity inherent in our field. -

Poder Y Estudios De Las Danzas En El Perú

!"! " !# $ ! " # $ %&&'( A Carmen y Lucho 2 CONTENIDO Resumen……………………………………………………………………………… 4 Introducción…………………………………………………………………………… 5 1. Inicio de los estudios de las danzas y el problema nacional (1900-1941).......................................................................................... 9 2. Avances en los estudios de las danzas, influencia de la antropología culturalista y continuación del debate sobre lo nacional (1942-1967)........................................................ 18 3. Estudios de las danzas y nacionalismo popular (1968-1980)…………………………………………………………....................... 37 4. Institucionalización de los estudios de las danzas (1981-2005)...................................................................................................... 48 Conclusiones: Hacia un balance preliminar de los estudios de las danzas en el Perú.................................................................... 62 Referencias bibliográficas................................................................................. 68 3 Resumen Esta investigación trata sobre las relaciones que se establecen entre el poder y los estudios de las danzas en el Perú, que se inician en las primeras décadas del siglo XX y continúan hasta la actualidad, a través del análisis de dos elementos centrales: El análisis del contexto social, político y cultural en que dichos estudios se realizaron; y el análisis del contenido de dichos estudios. El análisis evidencia y visibiliza las relaciones de poder no manifiestan -

THE FLAMENCO BOX in the CLASSROOM History , Evolution and Didactic Autor: Carlos Crisol Maestro

THE FLAMENCO BOX IN THE CLASSROOM History , Evolution and Didactic Autor: Carlos Crisol Maestro Coordinación de Diseño y Maquetación: Nuria Crisol de la Fuente Colaboración de los alumnos del CFGM Preimpresión en Artes Gráficas IES Santo Reino: Juan Jesús Mesa Moraleda y Gema Moreno Serrano en diseño de interiores y portada - contraportada. Traducción inglés: Nuria Sánchez INDEX I. PRECEDENTS AND ANALOGIES OF THE BOX Introduction and state of the issue Pg. 2 Searching for a box history in the world Pg. 3 The box in Perú: Findings documented on the origin of the box Pg. 5 The box in Cuba Pg. 7 The box in Spain: origin and evolution Pg. 8 . II. CONSTRUCTION OF THE BOX Building materials Pg. 12 Sundbox. Cubic capacity and dimensions of the box Pg. 14 Sound output: box hole (back, side, bottom ...) Pg. 15 Front or struck cover Pg. 18 String tension and tuning system. Treatment of harmonics. String arrangements in the box. Pg. 26 III. THE FLAMENCO BOX IN THE CLASSROOM Introduction Pg. 39 Objectives concretion Pg. 41 Subjects and curriculum areas relation: Pg. 43 Music Plastic and Visual education (Art) Language Social sciences, Geography and History Maths Physical education Languages Techology and Informatics Contribution to the Basic Competences: Pg. 45 Linguistic communication competence Mathematical competence Knowledge and interaction with the physical environment competence Information management and digital competence Social and citizen competence Cultural and Artistic competence Learning to learn competence Autonomy and self-esteem competence. IV. FLAMENCO BOX TEACHING AND LEARNING METHODS Pg. 48 V. BIBLIOGRAPHY. Pg. 51 1 Introduction and state of the issue. -

FOLK DANCER/ONLINE INDEX Vol. 1 No.1 (Summer 1969) to Vol. 51 No

FOLK DANCER/ONLINE INDEX Vol. 1 No.1 (Summer 1969) to Vol. 51 No. 5 (December 2020), inclusive Written by Karen Bennett. Not indexed: most editorials and like content written by editors while they hold that position; most letters, ads, cartoons, coming events, and photographs; and social announcements, sometimes made in a column whose title varied a lot, including “Hiers Ek Wiers,” “Tidbits,” “From the Grapevine” and “The Back Page”). Not all content was attributed (especially that of Walter Bye and Karen Bennett while they were editors), and reports by OFDA executives aren’t listed under their names, so this combination index/bibliography doesn’t include under a person’s name everything they wrote. Abbreviations used: ''AGM'' stands for Annual General Meeting, "bio" for biography, “fd” for folk dance, IFD for international folk dance,“info.” for information, "J/J/A" for June/July/August, and "OFDC" for Ontario Folk Dance Camp, and “IFDC” for the International Folk Dance Club, University of Toronto. The newsletter title has been variously OFDA, OFDA Newsletter, Ontario Folk Dance Association Newsletter, Ontario Folk Dance Association Magazine, Ontario Folkdancer, Ontario FolkDancer, Folk Dancer: The Magazine of World Dance and Culture, and Folk Dancer Online: The Magazine of World Dance and Culture. A Alaska: --folk dance cruise, Oct. 15/90 --visit by Ruth Hyde, J/J/A 85 Acadia, see French Canada Albania: Adams, Coby: obituary, J/J/A 86 --dance descriptions: Leši, Oct. 76; Valle Adamczyk, Helena: Jarnana, Jan. 15/96 (p. 8) --“Macedonian Celebration in Hamilton, 27 --dance words:Valle Jarnana, Jan. 15/96 (p. -

Level 2 Lesson 10 Visit to Peru

Level 2 Lesson 10 Visit to Peru Topics Prepare Before Class Describing traditions & life events Print copies of the student Activity Sheet. Expressing hopes & wishes Collect travel advertisements about different Musical traditions countries or print pages from the internet telling about cultural traditions in different countries for the writing activity. Learning Strategy Goals Use Sounds Wish & hope clauses Day 1 Introduce the Lesson Explain, “In Lesson 10, Anna is writing a story about the culture of Peru. She does not have time to travel, but her friend Bruna says she can learn about Peru in one short visit.” Ask, “Can you guess where Anna can learn about Peru?” Answers may include: at a library, in a museum, or at a festival. Teach Key Words Have students repeat the new words for this lesson after you say them. The list of words can be found in the Resources section. Choose a vocabulary practice activity from the How-To Guide to help students learn the new words. As the topic of this lesson is learning about cultural traditions and events, ask students to tell you about their hometown’s traditions, festivals or cultural events. Keep a list of key words related to the events. Write the words on the board and practice the pronunciation of any that may cause difficulty for your students. Let’s Learn English Level 2 Lesson 10 1 Day 2 Present the Conversation Tell students that the video will show Anna and her coworker Bruna at a museum. Play the video or audio of the conversation or hand out copies of the text from the Resources section. -

Mexico Popurri Coco “Recuerdame” & “Un Poco Loco”

OPENING All Dancers & Musicians Perform Mexico Popurri Coco “Recuerdame” & “Un poco loco” - Live Music “Son de la Negra” - Dance Puerto Rico (Plena) La Bomba” - Live Music Colombia Cumbia - La Pollera Colorá - Dance Salsa Caleña “ De Cali vengo” - Live Music & Dance Perú Marinera Norteña “Asi baila mi Trujillana” - Dance Venezuela “Venezuela” - Luis Silva - Live Music Repùblica Dominicana Bachata “Una bachata en Fukuoka” - Live Music & Dance Merengue “La travesia” - Live Music & Dance Brasil “Batucada” percussion musicians - Live Music - Drums Samba “ Bso Rio” - Dance Argentina Tango “Libertango” - Dance Boleadoras & Bombo - Dance & Featuring Performing Cuba “Afrocuban Chancleteo” - Live Music & Dance “Mambo & Conga” - Live Music & Dance Interactividad “Despacito” Interactivity Part At this time artists will call on students and teachers to come up to the stage and to follow instructions. OPENING All dancers & Musicians Perform Choreography that reflects the beat of Latin America. A call to dance and music from the wildest side of the origin of the first tribes. With this music, we open the way to other music and dance moves. Mexico To excite the souls of the little ones, this song inspired by Mexican popular music from the movie CoCo, will make us remember and feel the magic just like in the movie! POPURRI COCO “Recuérdame” Recuérdame, hoy me tengo que ir, mi amor Recuérdame, no llores, por favor Te llevo en mi corazón y cerca me tendrás A solas yo te cantaré soñando en regresar Recuérdame, aunque tenga que emigrar Recuérdame, si mi guitarra oyes llorar Ella con su triste canto te acompañará, hasta que en mis brazos tú estés Recuérdame.. -

Cartagena Y El Pasodoble

REVISTA DE INVESTIGACIÓN SOBRE FLAMENCO La madrugá Nº15, Diciembre 2018, ISSN 1989-6042 Cartagena y el pasodoble Benito Martínez del Baño Universidad Complutense de Madrid Enviado: 13-12-2018 Aceptado: 20-12-2018 Resumen El pasodoble es un tipo de composición musical menor con títulos de excepción, páginas musicales de gran factura melódica, fuerza expresiva y estructura perfecta. Muchas de sus composiciones han logrado inmortalizar el nombre de sus autores y el insuperable atractivo de dotar emoción nuestras fiestas, patronales y bravas. Podemos incluirlo como subgénero dentro de la composición zarzuelística, y encontrarlo de muy distintas maneras, como en tiempo de marchas aceleradas, alegres y bulliciosas pasadas del coro por la escena, breves y brillantes introducciones orquestales, también para bandas de música, y finales de cuadro o de acto, incluso con tintes flamencos. Asimismo títulos imprescindibles han sido compuestos en Cartagena y algunas de las más ilustres voces de esta tierra lo han cantado y otras aun lo incluyen en su repertorio. Palabras clave: pasodoble, Cartagena, flamenco, música popular. Abstract The pasodoble is a type of minor musical composition with exceptional titles, musical pages of great melodic design, expressive force and perfect structure. Many of his compositions have managed to immortalize the name of their authors and the insurmountable attraction of giving emotion to our festivities, patronal and brave. We can include it as a subgenre within the zarzuela composition, and find it in very different ways, such as in time of accelerated marches, happy and boisterous past of the choir for the scene, brief and brilliant orchestral introductions, also for bands, and end of picture or act, even with flamenco overtones. -

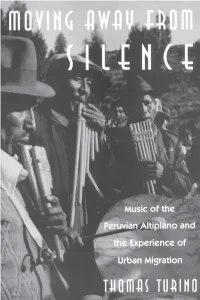

Moving Away from Silence: Music of the Peruvian Altiplano and the Experiment of Urban Migration / Thomas Turino

MOVING AWAY FROM SILENCE CHICAGO STUDIES IN ETHNOMUSICOLOGY edited by Philip V. Bohlman and Bruno Nettl EDITORIAL BOARD Margaret J. Kartomi Hiromi Lorraine Sakata Anthony Seeger Kay Kaufman Shelemay Bonnie c. Wade Thomas Turino MOVING AWAY FROM SILENCE Music of the Peruvian Altiplano and the Experience of Urban Migration THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS Chicago & London THOMAS TURlNo is associate professor of music at the University of Ulinois, Urbana. The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637 The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London © 1993 by The University of Chicago All rights reserved. Published 1993 Printed in the United States ofAmerica 02 01 00 99 98 97 96 95 94 93 1 2 3 4 5 6 ISBN (cloth): 0-226-81699-0 ISBN (paper): 0-226-81700-8 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Turino, Thomas. Moving away from silence: music of the Peruvian Altiplano and the experiment of urban migration / Thomas Turino. p. cm. - (Chicago studies in ethnomusicology) Discography: p. Includes bibliographical references and index. I. Folk music-Peru-Conirna (District)-History and criticism. 2. Folk music-Peru-Lirna-History and criticism. 3. Rural-urban migration-Peru. I. Title. II. Series. ML3575.P4T87 1993 761.62'688508536 dc20 92-26935 CIP MN @) The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences-Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI 239.48-1984. For Elisabeth CONTENTS List of Illustrations ix Acknowledgments xi Introduction: From Conima to Lima -

Music, Plants, and Medicine: Lamista Shamanism in the Age of Internationalization

MUSIC, PLANTS, AND MEDICINE: LAMISTA SHAMANISM IN THE AGE OF INTERNATIONALIZATION By CHRISTINA MARIA CALLICOTT A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2020 © 2020 Christina Maria Callicott In honor of don Leovijildo Ríos Torrejón, who prayed hard over me for three nights and doused me with cigarette smoke, scented waters, and cologne. In so doing, his faith overcame my skepticism and enabled me to salvage my year of fieldwork that, up to that point, had gone terribly awry. In 2019, don Leo vanished into the ethers, never to be seen again. This work is also dedicated to the wonderful women, both Kichwa and mestiza, who took such good care of me during my time in Peru: Maya Arce, Chabu Mendoza, Mama Rosario Tuanama Amasifuen, and my dear friend Neci. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation would not have been possible without the kindness and generosity of the Kichwa people of San Martín. I am especially indebted to the people of Yaku Shutuna Rumi, who welcomed me into their homes and lives with great love and affection, and who gave me the run of their community during my stay in El Dorado. I am also grateful to the people of Wayku, who entertained my unannounced visits and inscrutable questioning, as well as the people of the many other communities who so graciously received me and my colleagues for our brief visits. I have received support and encouragement from a great many people during the eight years that it has taken to complete this project.