Antioch and the Earthquake (115

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Revealing Jesus: the Historical Christ

Revealing Jesus: The Historical Christ St. Paul American Coptic Orthodox Church What do we know about Jesus? Can we prove the existence of God? NO Authorship of the Gospels Irenaeus, wri@ng about A.D. 180, confirmed the tradi@onal authorship: Mahew published his own Gospel among the Hebrews in their own tongue, when Peter and Paul were preaching the Gospel in Rome and founding the church there. A>er their departure, Mark, the disciple and interpreter of Peter, himself handed down to us in wri@ng the substance of Peter’s preaching. Luke, the follower of Paul, set down in a book the Gospel preached by his teacher. Then John, the disciple of the Lord, who also leaned on his breast, himself produced his Gospel while he was living at Ephesus in Asia. Strobel, Lee (2008-09-09). The Case for Christ: A Journalist's Personal Investigation of the Evidence for Jesus Dating the Gospels “The standard scholarly dang, even in very liberal circles, is Mark in the 70s, Mahew and Luke in the 80s, John in the 90s.” S@ll within the life@mes of various eyewitnesses of the life of Jesus. Strobel, Lee (2008-09-09). The Case for Christ: A Journalist's Personal Investigation of the Evidence for Jesus Paul Stating the Creed Perhaps the most important creed in terms of the historical Jesus is in 1 Corinthians 15: For what I received I passed on to you as of first importance: that Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures, that he was buried, that he was raised on the third day according to the Scriptures, and that he appeared to Peter, and then to the Twelve. -

The Church in the Roman Empire

The world prepared for the Christian Church VII. The world prepared for the gospel then and now A. There was very little progress after this 1. 1500s printing developed to set the stage for the protestant reformation so there would be a climate for God's truth 2. Industrial Revolution - 1800s a) Steam engine made production and travel increase enormously b) World never to be the same 3. Marconi invented radio 4. World ‘shrunk’ in size 5. TV, mass communications, and computers all happened in the last 150 years 6. Without these the gospel could not go out as effectively as it has. 7. The world has been prepared for God's work, and Christ's coming, today, just as it was for His first coming 1 The world prepared for the Christian Church VIII. Zenith of Roman Power - 46 B.C.- A.D.180 A. Caesars of Rome 1. Julius Caesar (46-44 B.C.) 2. Augustus Caesar (31 B.C- A.D.12) – prepared empire most for Christianity; birth of Jesus Christ c. 4 B.C. 3. Tiberius (12-37 A.D.) – crucifixion of Jesus A.D. 31 4. Caligula (37-41 A.D.) 5. Claudius (41-54 A.D.) 6. Nero (54-68 A.D.) – persecuted Christians; executed Paul 7. Galba (68-69 A.D.) 8. Otho, Vitelus (69 A.D.) 9. Vespasian (69-79 A.D.) – destroyed Jerusalem 10. Titus (79-81 A.D.) 11. Domitian (81-96 A.D.) – persecuted Christians 12. Hadrian (117-138 A.D.) 13. Marcus Aurelius (138-161 A.D.) 14. -

The Empire Strikes: the Growth of Roman Infrastructural Minting Power, 60 B.C

The Empire Strikes: The Growth of Roman Infrastructural Minting Power, 60 B.C. – A.D. 68 A dissertation submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Classics of the College of Arts and Sciences by David Schwei M.A., University of Cincinnati, December 2012 B.A., Emory University, May 2009 Committee Chairs: Peter van Minnen, Ph.D Barbara Burrell, Ph.D. ABSTRACT Coins permeated the Roman Empire, and they offer a unique perspective into the ability of the Roman state to implement its decisions in Italy and the provinces. This dissertation examines how this ability changed and grew over time, between 60 B.C. and A.D. 68, as seen through coin production. Earlier scholars assumed that the mint at Rome always produced coinage for the entire empire, or they have focused on a sudden change under Augustus. Recent advances in catalogs, documentation of coin hoards, and metallurgical analyses allow a fuller picture to be painted. This dissertation integrates the previously overlooked coinages of Asia Minor, Syria, and Egypt with the denarius of the Latin West. In order to measure the development of the Roman state’s infrastructural power, this dissertation combines the anthropological ideal types of hegemonic and territorial empires with the numismatic method of detecting coordinated activity at multiple mints. The Roman state exercised its power over various regions to different extents, and it used its power differently over time. During the Republic, the Roman state had low infrastructural minting capacity. -

Introduction Alice König and Christopher Whitton

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42059-4 — Roman Literature under Nerva, Trajan and Hadrian Edited by Alice König , Christopher Whitton Excerpt More Information Introduction Alice König and Christopher Whitton Among the Scrolls PictureyourselfinRomearoundad115,standinginthenewForumof Trajan. Beside you is the great equestrian statue of the emperor, before you the vast Basilica Ulpia, crowded with the usual mêlée of jurists and scribes, oicials and petitioners. High above its roof is another statue of Trajan, glinting down from the summit of his victory column. As you make your way further into the forum, your eye is caught by the colourful carvings on the column’s shaft; but you can’t help also being struck by the buildings that lank it, the two monumental wings of the Bibliotheca Ulpia.1 One of them houses a copy of Trajan’s Dacian war, a textual account of his Danu- bian victories to complement the triumphal scenes winding up the column outside.2 What other scrolls you might have found in this double library is now a matter of speculation. Archival material for sure, such as the prae- tors’ edicts that would one day be called up by Aulus Gellius;3 butitisa fair bet that literary works featured too,4 Greek and Latin.5 If so, here was a building grandly proclaiming its imperial patron’s investment in the writ- ten word, both documentary and literary, and in both world languages.6 The Bibliotheca Ulpia was not a public library as we know them, with bor- rowing rights and hushed reading rooms for research.7 As well as consulting the collection, visitors may have come to marvel at the statuary or attend 1 For an architectural description of the library, see Packer 2001: 78–9; on its position, Packer 1995: 353–4. -

Theophilus of Antioch

0165-0183 – Theophilus Antiochenus – Ad Autolycum Theophilus to Autolycus this file has been downloaded from: http://www.ccel.org/ccel/schaff/anf02.html Fathers of the Second Century Philip Schaff 85 THEOPHILUS OF ANTIOCH Introductory Note 867 TO THEOPHILUS OF ANTIOCH. [TRANSLATED BY THE REV. MARCUS DODS, A.M.] [A.D. 115–168–181.] Eusebius praises the pastoral fidelity of the primitive pastors, in their unwearied labours to protect their flocks from the heresies with which Satan contrived to endanger the souls of believers. By exhortations and admonitions, and then again by oral discussions and refutations, contending with the heretics themselves, they were prompt to ward off the devouring beasts from the fold of Christ. Such is the praise due to Theophilus, in his opinion; and he cites especially his lost work against Marcion as “of no mean character.”521 He was one of the earliest commentators upon the Gospels, if not the first; and he seems to have been the earliest Christian historian of the Church of the Old Testament. His only remaining work, here presented, seems to have originated in an “oral discussion,” such as Eusebius instances. But nobody seems to accord him due praise as the founder of the science of Biblical Chronology among Christians, save that his great successor in modern times, Abp. Usher, has not forgotten to pay him this tribute in the Prolegomena of his Annals. (Ed. Paris, 1673.) Theophilus occupies an interesting position, after Ignatius, in the succession of faithful men who represented Barnabas and other prophets and teachers of Antioch,522 in that ancient seat, from which comes our name as Christians. -

Rule and Revenue in Egypt and Rome: Political Stability and Fiscal Institutions

Princeton/Stanford Working Papers in Classics Rule and Revenue in Egypt and Rome: Political Stability and Fiscal Institutions Version 1.0 August 2007 Andrew Monson Stanford University Abstract: This paper investigates what determines fiscal institutions and the burden of taxation using a case study from ancient history. It evaluates Levi’s model of taxation in the Roman Republic, according to which rulers’ high discount rates in periods of political instability encourage them to adopt a more predatory fiscal regime. The evidence for fiscal reform in the transition from the Republic to the Principate seems to support her hypothesis but remains a matter of debate among historians. Egypt’s transition from a Hellenistic kingdom to a Roman province under the Principate provides an analogous case for which there are better data. The Egyptian evidence shows a correlation between rulers’ discount rates and fiscal regimes that is consistent with Levi’s hypothesis. © Andrew Monson. [email protected] 1 Explicit rational choice models are rare in studies of Greek and Roman political history.1 Most ancient historians avoid discussing the underlying behavioral assumptions of politics and opening them to criticism or potential falsification. Often the impetus for theoretical debate has to come from social scientists willing to venture into ancient history. The topic of this paper was treated in one chapter of Levi’s book Of Rule and Revenue (1988), which introduces a rational choice model for Roman taxation. The latter is part of the growing social -

Margaret M. Roxan the Earliest Extant Diploma of Thrace, Ad

EVGENI I. PAUNOV – MARGARET M. ROXAN THE EARLIEST EXTANT DIPLOMA OF THRACE, A.D. 114 (= RMD I 14) aus: Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 119 (1997) 269–279 © Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH, Bonn 269 THE EARLIEST EXTANT DIPLOMA OF THRACE, A.D. 114 (= RMD I 14)* A diploma was found in the village of Pissarevo, near Dolna Orjahovitsa, District of Veliko Tarnovo, Central North Bulgaria, before 1945. The site is on the left bank of the river Jantra (Iatrus), ca. 20 km south-east of the Roman town Nicopolis ad Istrum, and was within its territory (regio Nicopolitana). It is presently in the collection of the Department of Classical Antiquities at the National Museum of Archaeology in Sofia (inv. no. A 8416). The diploma was given to the late academician Prof. D. P. Dimitrov in 1945.1 In 1976 it was described and placed in the inventory of the Museum by Dr. V. Gerassimova-Tomova after it had been brought to the Museum by Dr. M. Chichikova, widow of Professor Dimitrov, in 1974. (National Archaeological Museum, photo neg. no. ‘74/1486-1494.) The diploma is almost complete although sections of both tablets are now missing. On the outer face of tabella I the upper margin and two complete lines of script and part of the third are lost. The remainder of this tablet is represented by one large and two smaller fragments which join together but lack a triangular segment from the side of the lower right quadrant and an irregular section of the bottom edge, which creates a gap in the last three lines of text. -

Egypt After the Pharaohs: 332 BC-AD

EGYPT after the Pharaohs Alan K Bowman EGYPT after the Pharaohs 332 BC-AD 642 from Alexander to the Arab Conquest UNIVERSITY OE CALllORNIA PRESS BERKELEY AND LOS ANGELES r i</86 Alan k. Bownun Published by the I'nivcrsitv of < !a|ift irnta Press in ilie I'niied Siato 1986 First [xiperlrjck printing 1989 Second paperback printing 1996 Library ot'Oingrcsii (Jtalo^uing-in-Pulilicniion Data Bowman. Alan K. I'gypi after rhepharaohs. tw u.r. \.i>. (142. Bibliography: p. Includes index. 1. l\u\pt (.'ivili/aiinn it: iu:. fi;H A.D. I. "I'itle mVii.lttii 1986 y\x'.oi 86 inn ISBN o 52020s 11-G Printed in I long Kong 12 m ft i x 9 Contents Acknowledgements 6 Preface 2 Note on Conventions 8 List of lllusrriitions 8 i The (iift of the Nile u 2 The Ruling Power 21 3 State and Subject s 5 4 Poverty and Prosperity 89 5 Greeks and Egyptians 121 6 Gods, Temples and Churches i6j 7 Alexandria, Queen of the Mediterranean 203 8 Epilogue 2$4 Appendix I The Reigns of the Ptolemies 2 s S Appendix II Metrology and Currency 236 Appendix III The Archaeological Evidence M9 Appendix IV Additional Notes 242 Footnotes 345 Bibliography ip Index 26s Ackno w 1 edgemcnts National Trust (The Calkc Gardner Wilkinson Papers. Bodleian Library, Oxford): 10, 34, 52, Acknowledgement is made to the following for J J. 82 permission to reproduce illustrations: Pctrie Museum, University College. London: 6 Royal Scottish Museum, Edinburgh: 63 Antikenmuscum, Staatlichc Musecn, Prcuss- Scala, Florence: t, 45, 71, 112 ischer Kulturbcsitz, Berlin: i \ Dr H. -

Christian Communities in Western Asia Minor Into the Early Second Century: Ignatius and Others As Witnesses Against Bauer

JETS 49/1 (March 2006) 17–44 CHRISTIAN COMMUNITIES IN WESTERN ASIA MINOR INTO THE EARLY SECOND CENTURY: IGNATIUS AND OTHERS AS WITNESSES AGAINST BAUER paul trebilco* i. introduction Walter Bauer’s book Rechtgläubigkeit und Ketzerei im ältesten Chris- tentum was published in 1934. The English translation, entitled Orthodoxy and Heresy in Earliest Christianity and published in 1971,1 gave the book a new lease on life. This book has had a significant impact on scholarship on the NT and the early Church. It is to this work and its legacy that I will devote this paper. Bauer summarized his argument in this way: “Perhaps—I repeat, per- haps—certain manifestations of Christian life that the authors of the church renounce as ‘heresies’ originally had not been such at all, but, at least here and there, were the only form of the new religion—that is, for those regions they were simply ‘Christianity.’ The possibility also exists that their adherents constituted the majority, and that they looked down with hatred and scorn on the orthodox, who for them were the false believers.”2 Both chronological and numerical dimensions were important in Bauer’s argument. He thought that what would later be called heresy was often “primary” and hence the original form of Christianity, and that in some places and at some times, heresy had a numerical advantage and outnumbered what came to be called orthodoxy.3 * Paul Trebilco is professor and head of the department of theology and religious studies at The University of Otago, P.O. Box 56, Dunedin, New Zealand. -

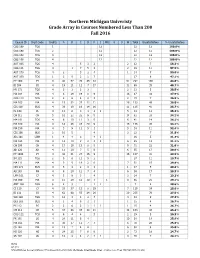

Northern Michigan Univeristy Grade Array in Courses Numbered Less Than 200 Fall 2016

Northern Michigan Univeristy Grade Array in Courses Numbered Less Than 200 Fall 2016 Course ID Dept Code Credits A B C D F I MG S U W Total Unsatisfactory % Unsatisfactory COS 198 TOS 1 12 12 12 100.0% COS 198 TOS 2 12 12 12 100.0% COS 198 TOS 3 12 12 12 100.0% COS 198 TOS 4 12 12 12 100.0% AUT 105 TOS 4 5 3 2 2 12 7 58.3% COS 111 TOS 4 1 7 5 4 2 19 11 57.9% AUT 170 TOS 4 2 5 2 4 1 14 7 50.0% AUT 100 TOS 1 2 5 2 1 7 17 8 47.1% PY 100L PY 4 40 57 70 45 33 52 297 130 43.8% BI 104 BI 4 19 21 11 7 17 11 86 35 40.7% HV 172 TOS 4 3 3 2 3 2 13 5 38.5% MA 104 MA 4 6 29 19 8 9 16 87 33 37.9% COS 113 TOS 8 2 6 4 2 3 2 19 7 36.8% MA 103 MA 4 15 32 37 12 11 26 133 49 36.8% CIS 110 BUS 4 39 19 16 14 16 11 115 41 35.7% PL 160 PL 4 11 8 3 4 2 1 5 34 12 35.3% CH 112 CH 5 10 22 22 9 5 14 82 28 34.1% HM 101 TOS 4 6 10 11 3 5 6 41 14 34.1% MA 100 MA 4 18 36 37 20 9 16 136 45 33.1% MA 150 MA 4 3 9 11 5 1 5 34 11 32.4% CIS 100 BUS 2 10 5 4 3 22 7 31.8% AIS 101 LIBR 1 4 4 3 4 1 16 5 31.3% MA 163 MA 4 14 10 8 2 3 3 6 45 14 31.1% CH 109 CH 4 17 19 13 8 5 9 71 22 31.0% AD 120 AD 4 11 20 7 5 6 6 55 17 30.9% PY 100S PY 4 38 31 27 16 9 16 137 41 29.9% IM 115 TOS 2 9 6 11 9 2 37 11 29.7% MA 111 MA 4 9 9 18 2 6 7 51 15 29.4% OIS 171 BUS 4 6 4 2 3 1 1 17 5 29.4% AS 103 PH 4 9 20 12 7 4 6 58 17 29.3% LPM 101 CJ 4 5 9 3 4 3 24 7 29.2% MA 090 MA 4 15 29 16 10 7 1 8 86 25 29.1% AMT 102 TOS 6 2 3 1 1 7 2 28.6% CJ 110 CJ 4 35 37 13 8 19 7 119 34 28.6% BI 111 BI 4 62 68 55 24 26 20 255 70 27.5% WD 180 TOS 4 18 3 3 2 4 3 33 9 27.3% OIS 183 BUS 4 1 4 6 2 1 1 15 4 26.7% PS 112 -

Voihnitakottiosi

TURAL HI PTORY CANAGONA WILADCZa4. voihnitaK ottiosi • .7° erc I a IMO% 0‘ 11 a 111 #141..■ V .4 t - - ° , . ,.. ...it. **.t. ,:- ■■,4 • . t •• — a , -. , ."; * -- . .• • - . 7.-7- ;„_*^C. 7,1. -- - :*:::2 -::' ::-. .-'Z ..- ...# "`..,...-- 4*-'- *-...1 •-- TA '' .gs"i".',..•'...z'.,:z.' • `•*: "*-- ".**, **-,-;. 4 ......, - ,... -,„,_.,...,.,.... z.,, .....4 s- --.... ----- •- ...e -. • _ ,-....0-1c 4.. .,. ..--.." ..,k ..: ,....... - •---..---_ ,..., .... ;••••• 4 4.:4,..A% qw,lb.......... r,,,....._-."•-----.. , - - --. „ ..r........ , ..... -..,........ ....... _ I ..:11i,,,, ..- *. p ,..".„. --, , - ...1 ..,. '"" .......... - ...;,. ..P..** .... •,-, -*-- . ,.... 'nes.. ,,,,__fir,_ ''''' _ '`w• e _ z ,-- • 'At''1 , • A CULTURAL HISTORY OF THE CANACONA TALUKA OF GOA THESIS submitted to GOA UNIVERSITY for the award of the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in HISTORY by PANDURANG R. PHALDESAI under the guidance of DR. PRATIMA P. KAMAT, Head, Department of History, Goa University. 1 k ■ ) (1) (2X7D3 (./?_ K-ec- vt 4:VT) ► DECLARATION [ under 0.19.800 1 This thesis is based entirely on the original work carried out by me under the guidance of Dr. Pratima Kamat. To the best of my knowledge, the present study is the first comprehensive work of its kind from the area mentioned. The literature related to the problem investigated has been surveyed and list of references is appended. Due acknowledgements have been made wherever outside facilities and suggestions have been availed of. I hereby declare that the thesis or part thereof has not been published anywhere or in other form. It has not been previously submitted by me for a degree of any university. Certified that the above statement made by the candidate is correct. ( r. Pratima K t) Guide CERTIFICATE [ under 0.19.8 (vi)] This is to certify that the thesis entitled "A Cultural History of the Canacona Taluka of Goa." submitted by Pandurang R. -

NYU Abu Dhabi Bulletin 2014-2015

NYU ABU DHABI BULLETIN 2014–15 2 2014–15 | DEPARTMENT | MAJOR NEW YORK UNIVERSITY ABU DHABI BULLETIN 2014–15 Please note that this pdf was last edited on September 9, 2014, this subsequent to the printed edition. NYU Abu Dhabi Saadiyat Campus PO Box 129188 Abu Dhabi United Arab Emirates The policies, requirements, course offerings, and other information set forth in this bulletin are subject to change without notice and at the discretion of the administration. For the most current information, please see nyuad.nyu.edu. INTRODUCTION 340 Graduation Honors 340 Incompletes 4 Welcome from Vice Chancellor 340 Integrity Commitment Alfred H. Bloom 340 Leave of Absence 6 Educating Global Leaders 341 Midterm Assessment 8 About Abu Dhabi: A New World City 341 Minimum Grades 9 Pathway to the Professions 341 Pass/Fail 342 Religious Holidays BASIC INFORMATION 342 Repeating Courses 342 Transcripts 12 Programs at a Glance 343 Transfer Credit 14 Academic Calendar 343 Withdrawal from a Course 16 Language of Instruction 16 Accreditation STUDENT AFFAIRS AND CAMPUS LIFE 16 Degrees and Graduation Requirements 19 Admissions 345 Advisement and Mentoring 345 Office of First-Year Programming COURSES OF INSTRUCTION 346 Career Services, Internships, Global Awards, and Pre-Professional Advising 22 The Core Curriculum 346 Office of Community Outreach 58 Arts and Humanities 347 Fitness, Sports and Recreation 140 Social Science 348 Health and Wellness Services 180 Science and Mathematics 348 Student Activities 228 Engineering 349 Religious Life 254 Multidisciplinary