Voihnitakottiosi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Pre-Severan Diplomata and the Problem of 'Special Grants."' In

DuSaniC, Slobodan. "Pre-Severan Diplomata and the Problem of 'Special Grants."' In Heer und Integrationspolitik: Die Romischen Militardiplome als historische Quelle, edited by Werner Eck and Hartmut Wolff, 190-240. Koln: Bohlau, 1986. HEER UND INTEGRATIONSPOLITIK Die romischen Militardiplome als historische Quelle herausgegeben von WERNER ECK und HARTMUT WOLFF 1986 BOHLAU VERLAG KOLNWIEN The Problem of 'Special Grants' 191 ly (the exclusion of candidates from the provincial forces) and statisti- cally, and certainly appears more difficult to assess from the stand- point of the radical conception5. The following argumentation is Pre-Severan Diplomata and the Problem centred around the salient points of the radical theory susceptible of of 'Special Grants' modification or improvement when one considers how they have been treated in recent scholarship. Many remaining details will be Von dealt with subsequently, in other places. Slobodan DuSaniC (1) The fundamental difficulty with the (so-called) traditional thesis6,which takes the 'normal' diploma as an automatic reward for every man having spent, in major non-legionary troops, the pre- This paper has been written' in the conviction that the (so-called) scribed term of service (XXV plurave stipendia for the auxiliaries, radical theory, which "postulates that virtually all the constitutions/ XXVI [XXVIIAplurave stipendia for the sailors), arises from the indi- diplomata name only those units/soldiers possessing extraordinary cations that the material known so far (CIL XVI + RMD I + RMD 11) meritu2(mainly participants in expeditiones belli but also in certain markedly deviates from the numbers to be expected in view of the peacetime efforts3 matching, in importance, such expeditions), pro- effectives of certain units, classes of soldiers and provincial armies vides the most economical basis for interpreting the extremely com- plex features of the diplomata militaria as a documentary genre. -

Roman Conquest, Occupation and Settlement of Wales AD 47–410

no nonsense Roman Conquest, Occupation and Settlement of Wales AD 47–410 – interpretation ltd interpretation Contract number 1446 May 2011 no nonsense–interpretation ltd 27 Lyth Hill Road Bayston Hill Shrewsbury SY3 0EW www.nononsense-interpretation.co.uk Cadw would like to thank Richard Brewer, Research Keeper of Roman Archaeology, Amgueddfa Cymru – National Museum Wales, for his insight, help and support throughout the writing of this plan. Roman Conquest, Occupation and Settlement of Wales AD 47-410 Cadw 2011 no nonsense-interpretation ltd 2 Contents 1. Roman conquest, occupation and settlement of Wales AD 47410 .............................................. 5 1.1 Relationship to other plans under the HTP............................................................................. 5 1.2 Linking our Roman assets ....................................................................................................... 6 1.3 Sites not in Wales .................................................................................................................... 9 1.4 Criteria for the selection of sites in this plan .......................................................................... 9 2. Why read this plan? ...................................................................................................................... 10 2.1 Aim what we want to achieve ........................................................................................... 10 2.2 Objectives............................................................................................................................. -

Ch. 3 MALE DEITIES I. Worship of Vishnu and Its Forms in Goa Vishnu

Ch. 3 MALE DEITIES I. Worship of Vishnu and its forms in Goa Vishnu is believed to be the Preserver God in the Hindu pantheon today. In the Vedic text he is known by the names like Urugai, Urukram 'which means wide going and wide striding respectively'^. In the Rgvedic text he is also referred by the names like Varat who is none other than says N. P. Joshi^. In the Rgvedhe occupies a subordinate position and is mentioned only in six hymns'*. In the Rgvedic text he is solar deity associated with days and seasons'. References to the worship of early form of Vishnu in India are found in inscribed on the pillar at Vidisha. During the second to first century BCE a Greek by name Heliodorus had erected a pillar in Vidisha in the honor of Vasudev^. This shows the popularity of Bhagvatism which made a Greek convert himself to the fold In the Purans he is referred to as Shripati or the husband oiLakshmi^, God of Vanmala ^ (wearer of necklace of wild flowers), Pundarikaksh, (lotus eyed)'". A seal showing a Kushan chief standing in a respectful pose before the four armed God holding a wheel, mace a ring like object and a globular object observed by Cunningham appears to be one of the early representations of Vishnu". 1. Vishnu and its attributes Vishnu is identified with three basic weapons which he holds in his hands. The conch, the disc and the mace or the Shankh. Chakr and Gadha. A. Shankh Termed as Panchjany Shankh^^ the conch was as also an essential element of Vishnu's identity. -

Great Cloud of Witnesses.Indd

A Great Cloud of Witnesses i ii A Great Cloud of Witnesses A Calendar of Commemorations iii Copyright © 2016 by The Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society of The Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America Portions of this book may be reproduced by a congregation for its own use. Commercial or large-scale reproduction for sale of any portion of this book or of the book as a whole, without the written permission of Church Publishing Incorporated, is prohibited. Cover design and typesetting by Linda Brooks ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-962-3 (binder) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-966-1 (pbk.) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-963-0 (ebook) Church Publishing, Incorporated. 19 East 34th Street New York, New York 10016 www.churchpublishing.org iv Contents Introduction vii On Commemorations and the Book of Common Prayer viii On the Making of Saints x How to Use These Materials xiii Commemorations Calendar of Commemorations Commemorations Appendix a1 Commons of Saints and Propers for Various Occasions a5 Commons of Saints a7 Various Occasions from the Book of Common Prayer a37 New Propers for Various Occasions a63 Guidelines for Continuing Alteration of the Calendar a71 Criteria for Additions to A Great Cloud of Witnesses a73 Procedures for Local Calendars and Memorials a75 Procedures for Churchwide Recognition a76 Procedures to Remove Commemorations a77 v vi Introduction This volume, A Great Cloud of Witnesses, is a further step in the development of liturgical commemorations within the life of The Episcopal Church. These developments fall under three categories. First, this volume presents a wide array of possible commemorations for individuals and congregations to observe. -

Tribal Women's Livelihood In

3rd KANITA POSTGRADUATE INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON GENDER STUDIES 16 – 17 November 2016 Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang Tribal Women’s Livelihood in Goa: a Daily Struggle with the Nature and the Nurture Priyanka Velip Government College of Arts, Science and Commerce, Quepem-Goa Goa University, India Corresponding Email: [email protected] Abstract Life for tribal women has become a daily struggle due to inflation and the high cost of living in ‘touristic’ Goa as well as government policy regarding their traditional source of livelihood – namely kumeri or shifting cultivation. This has been a common practice among the tribal communities in several parts of India. It has been called by different names, for example jhum cultivation in North India, slash and burn, swidden agriculture etc. In Goa, shifting cultivation is locally known as kumeri cultivation or kaamat in Konkani. This paper is an attempt to document the daily struggles of the women in my own community the Velip community, which is considered as one of the Tribal communities of Goa. Tribal communities seem to be closer to nature because of geographical settlement and therefore they are highly dependent on nature as a means of livelihood. But now days because of government policy, forest laws, etc., the community has been denied access to land and other natural resources making survival by this traditional source of livelihood difficult. The present paper deals with the necessity of the tribal people especially poor Velip women who are more dependent on natural resources as means of livelihood and whose search for alternates is the highlight of this paper. -

List of Recognised Educational Institutions in Goa 2010

GOVERNMENT OF GOA LIST OF RECOGNISED EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS IN GOA 2010 - 2011 AS ON 30-09-2010 DIRECTORATE OF EDUCATION STATISTICS SECTION GOVERNMENT OF GOA PANAJI – GOA Tel: 0832 2221516/2221508 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.education.goa.gov.in GOVERNMENT OF GOA LIST OF RECOGNISED EDUCATIONAL INSTITUTIONS IN GOA 2010 - 2011 AS ON 30-09-2010 DIRECTORATE OF EDUCATION STATISTICS SECTION GOVERNMENT OF GOA PANAJI – GOA Tel: 0832 2221516/2221508 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.education.goa.gov.in C O N T E N T Sr. No. Page No. 1. Affiliated Colleges and Recognized Institutions in Goa [Non- Professional] … … … 1 2. Affiliated Colleges and Recognized Institutions in Goa [Professional] … … … … 5 3. Institutions for Professional/Technical Education in Goa [Post Matric Level] … … … 8 4. Institutions for Professional/Technical/Other Education in Goa [School Level]… … … 13 5. Higher Secondary Schools: Government and Government Aided & Unaided … … … 14 6. Government Aided & Unaided High Schools [North Goa District] … … … … … 22 7. Government Aided & Unaided High Schools [South Goa District] … … … … … 31 8. Government Aided & Unaided Middle Schools [North Goa District] … … … … 37 9. Government Aided & Unaided Middle Schools [South Goa District] … … … … 38 10. Government Aided & Unaided Primary Schools [North Goa District] … … … … 39 11. Government Aided & Unaided Primary Schools [South Goa District] … … … … 48 12. Government High Schools (Central and State) … … … … … … … … 56 13. Government Middle Schools [North & South Goa Districts] … … … … … … 60 14. Government Primary Schools [North Goa District] … … … … … … … 63 15. Government Primary Schools [South Goa District] … … … … … … … 87 16. Special Schools … … … … … … … … … … … … … 103 17. National Open Schools … … … … … … … … … … … … 104 AFFILIATED COLLEGES AND RECOGNISED INSTITUTIONS IN GOA [NON – PROFESSIONAL] Sr. -

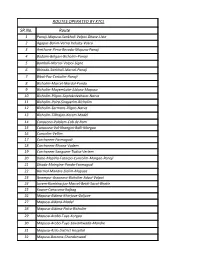

Samaj Laghubitta Bittiya Sanstha Ltd. Demat Shareholder List S.N

SAMAJ LAGHUBITTA BITTIYA SANSTHA LTD. DEMAT SHAREHOLDER LIST S.N. BOID Name Father Name Grandfather Name Total Kitta Signature 1 1301010000002317 SHYAM KRISHNA NAPIT BHUYU LAL NAPIT BHU LAL NAPIT / LAXMI SHAKYA NAPIT 10 2 1301010000004732 TIKA BAHADUR SANJEL LILA NATHA SANJEL DUKU PD SANJEL / BIMALA SANJEL 10 3 1301010000006058 BINDU POKHAREL WASTI MOHAN POKHAREL PURUSOTTAM POKHAREL/YADAB PRASAD WASTI 10 4 1301010000006818 REJIKA SHAKYA DAMODAR SHAKYA CHANDRA BAHADUR SHAKYA 10 5 1301010000006856 NIRMALA SHRESTHA KHADGA BAHADUR SHRESTHA LAL BAHADUR SHRESTHA 10 6 1301010000007300 SARSWATI SHRESTHA DHUNDI BHAKTA RAJLAWAT HARI PRASAD RAJLAWAT/SAROJ SHRESTHA 10 7 1301010000010476 GITA UPADHAYA SHOVA KANTA GNAWALI NANDA RAM GNAWALI 10 8 1301010000011636 SHUBHASINNI DONGOL SURYAMAN CHAKRADHAR SABIN DONGOL/RUDRAMAN CHAKRADHAR 10 9 1301010000011898 HARI PRASAD ADHIKARI JANAKI DATTA ADHIKARI SOBITA ADHIKARI/SHREELAL ADHIKARI 10 10 1301010000014850 BISHAL CHANDRA GAUTAM ISHWAR CHANDRA GAUTAM SAMJHANA GAUTAM/ GOVINDA CHANDRA GAUTAM 10 11 1301010000018120 KOPILA DHUNGANA GHIMIRE LILAM BAHADUR DHUNGANA BADRI KUMAR GHIMIRE/ JAGAT BAHADUR DHUNGANA10 12 1301010000019274 PUNESHWORI CHAU PRADHAN RAM KRISHNA CHAU PRADHAN JAYA JANMA NAKARMI 10 13 1301010000020431 SARASWATI THAPA CHITRA BAHADUR THAPA BIRKHA BAHADUR THAPA 10 14 1301010000022650 RAJMAN SHRESTHA LAXMI RAJ SHRESTHA RINA SHRESTHA/ DHARMA RAJ SHRESTHA 10 15 1301010000022967 USHA PANDEY BHAWANI PANDEY SHYAM PRASAD PANDEY 10 16 1301010000023956 JANUKA ADHIKARI DEVI PRASAD NEPAL SUDARSHANA ADHIKARI -

Journal of the Transactions Of

JOURNAL OF THE TRANSACTIONS OF OR. VOL. LXVI. LONDON: ~ubliit.Jel:r tiv tbt lnititute, 1, (IJ;mtra:l 3Suill:ringi, i!lllfdtmin,ter, •·m. 1. A L L R I G H T S R JC B E R V E D, 1934 781sT ORDINARY GENERAL MEETING, HELD IN COMMITTEE ROOM B, THE CENTRAL HALL, WESTMINSTER, S.W.l, ON MONDAY, MAY 28TH, 1934, A.T 4.30 P.M. LIEUT.-COLONEL ARTHUR KENNEY-HERBERT IN THE CHAIR. The Minutes of the previous Meeting were read, confirmed, and signed, and the HoN. SECRETARY announced the election of Robert J. Nairn, Esq., B.Sc., Ph.C., as an Associate. The CHAIRMAN then called on the Rev. John Stewart, Ph.D., to read his paper on "The Dates of Our Lord's Life and Ministry." THE DATES OF OUR WRD'S LIFE AND MINISTRY. By THE REV. JOHN STEWART, Ph.D. HERE are only three dates in our Lord's Life regarding T which the Scriptures give any definite information, but these are quite sufficient for our purpose. They are (1) The date of the Nativity; (2) The date when He began His public ministry ; and (3) The date of the Crucifixion. As regards the first of these the information given enables us to determine the year with practical certainty, the month and the day can be arrived at only approximately. The second is closely related to the time when John the Baptist began his work as forerunner, a year which is definitely known. How soon after John's appearance our Lord began His ministry is somewhat uncertain. -

In the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit

Case: 17-17531, 04/02/2018, ID: 10821327, DktEntry: 13-1, Page 1 of 111 IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE NINTH CIRCUIT WINDING CREEK SOLAR LLC, Case No. 17-17531 Plaintiff-Appellant, On Appeal from the United States v. District Court for the Northern District of California CARLA PETERMAN; MARTHA No. 3:13-cv-04934-JD GUZMAN ACEVES; LIANE Hon. James Donato RANDOLPH; CLIFFORD RECHTSCHAFFEN; MICHAEL PICKER, in their official capacities as Commissioners of the California Public Utilities Commission, Defendants-Appellees. Case No. 17-17532 WINDING CREEK SOLAR LLC, On Appeal from the United States Plaintiff-Appellee, District Court for the Northern District v. of California No. 3:13-cv-04934-JD CARLA PETERMAN; MARTHA Hon. James Donato GUZMAN ACEVES; LIANE RANDOLPH; CLIFFORD RECHTSCHAFFEN; MICHAEL PICKER, in their official capacities as Commissioners of the California Public Utilities Commission, Defendants-Appellants. APPELLANT’S FIRST BRIEF ON CROSS-APPEAL Thomas Melone ALLCO RENEWABLE ENERGY LTD. 1740 Broadway, 15th Floor New York, NY 10019 Telephone: (212) 681-1120 Email: [email protected] Attorneys for Appellant WINDING CREEK SOLAR LLC Case: 17-17531, 04/02/2018, ID: 10821327, DktEntry: 13-1, Page 2 of 111 CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT Winding Creek Solar LLC is 100% owned by Allco Finance Limited, which is a privately held company in the business of developing solar energy projects. Allco Finance Limited has no parent companies, and no publicly held company owns 10 percent or more of its stock. /s/ Thomas Melone i Case: 17-17531, 04/02/2018, ID: 10821327, DktEntry: 13-1, Page 3 of 111 TABLE OF CONTENTS CORPORATE DISCLOSURE STATEMENT ................................................... -

The Tradition of Serpent Worship in Goa: a Critical Study Sandip A

THE TRADITION OF SERPENT WORSHIP IN GOA: A CRITICAL STUDY SANDIP A. MAJIK Research Student, Department of History, Goa University, Goa 403206 E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: As in many other States of India, the State of Goa has a strong tradition of serpent cult from the ancient period. Influence of Naga people brought rich tradition of serpent worship in Goa. In the course of time, there was gradual change in iconography of serpent deities and pattern of their worship. There exist a few writings on serpent worship in Goa. However there is much scope to research further using recent evidences and field work. This is an attempt to analyse the tradition of serpent worship from a historical and analytical perspective. Keywords: Nagas, Tradition, Sculpture, Inscription The Ancient World The Sanskrit word naga is actually derived from the word naga, meaning mountain. Since all the Animal worship is very common in the religious history Dravidian tribes trace their origin from mountains, it of the ancient world. One of the earliest stages of the may probably be presumed that those who lived in such growth of religious ideas and cult was when human places came to be called Nagas.6 The worship of serpent beings conceived of the animal world as superior to deities in India appears to have come from the Austric them. This was due to obvious deficiency of human world.7 beings in the earliest stages of civilisation. Man not equipped with scientific knowledge was weaker than the During the historical migration of the forebears of animal world and attributed the spirit of the divine to it, the modern Dravidians to India, the separation of the giving rise to various forms of animal worship. -

SR.No. Route ROUTES OPERATED by KTCL

ROUTES OPERATED BY KTCL SR.No. Route 1 Panaji-Mapusa-Sankhali-Valpoi-Dhave-Uste 2 Agapur-Borim-Verna Industy-Vasco 3 Amthane-Pirna-Revoda-Mapusa-Panaji 4 Badami-Belgavi-Bicholim-Panaji 5 Bamboli-Marcel-Valpoi-Signe 6 Bhiroda-Sankhali-Marcel-Panaji 7 Bibal-Paz-Cortalim-Panaji 8 Bicholim-Marcel-Mardol-Ponda 9 Bicholim-MayemLake-Aldona-Mapusa 10 Bicholim-Pilgao-Saptakoteshwar-Narva 11 Bicholim-Poira-Sinquerim-Bicholim 12 Bicholim-Sarmans-Pilgao-Narva 13 Bicholim-Tikhajan-Kerem-Madel 14 Canacona-Palolem-Cab de Ram 15 Canacona-Val-Khangini-Balli-Margao 16 Cuncolim-Vellim 17 Curchorem-Farmagudi 18 Curchorem-Rivona-Vadem 19 Curchorem-Sanguem-Tudva-Verlem 20 Dabe-Mopirla-Fatorpa-Cuncolim-Margao-Panaji 21 Dhada-Maingine-Ponda-Farmagudi 22 Harmal-Mandre-Siolim-Mapusa 23 Ibrampur-Assonora-Bicholim-Advoi-Valpoi 24 Juvem-Kumbharjua-Marcel-Betki-Savoi-Bhatle 25 Kawar-Canacona-Rajbag 26 Mapusa-Aldona-Khorjuve-Goljuve 27 Mapusa-Aldona-Madel 28 Mapusa-Aldona-Poira-Bicholim 29 Mapusa-Arabo-Tuye-Korgao 30 Mapusa-Arabo-Tuye-Sawantwada-Mandre 31 Mapusa-Azilo District Hospital 32 Mapusa-Bastora-Chandanwadi 33 Mapusa-Bicholim-Poira 34 Mapusa-Bicholim-Sankhali-Valpoi-Hivre 35 Mapusa-Calvi-Madel 36 Mapusa-Carona-Amadi 37 Mapusa-Colvale-Dadachiwadi-Madkai 38 Mapusa-Duler-Camurli 39 Mapusa-Karurli-Aldona-Pomburpa-Panaji 40 Mapusa-Khorjuve-Bicholim-Varpal 41 Mapusa-Marna-Siolim 42 Mapusa-Nachnola-Carona-Calvi 43 Mapusa-Palye-Succuro-Bitona-Panaji 44 Mapusa-Panaji-Fatorpha(Sunday) 45 Mapusa-Pedne-Pednekarwada-Mopa 46 Mapusa-Saligao-Calangute-Pilerne-Panaji 47 Mapusa-Siolim -

Dormant Account 10 Years and Above As on Ashadh 2076

Everest Bank Limited Head Office, Lazimpat 14th Aug 2019 DORMANT ACCOUNT 10 YEARS AND ABOVE AS ON ASHADH 2076 SN A/C NAME CURRENCY 1 BIRENDRA & PUNAMAYA EUR 2 ROBERT PRAETZEL EUR 3 NABARAJ KOIRALA EUR 4 SHREE NAV KANTIPUR BAHUUD NPR 5 INTERCONTINENTAL KTM HOTE NPR 6 KANHIYALAL & RAJESH OSWAL NPR 7 LAXMI HARDWARE NPR 8 NAVA KSHITIZ ENTERPRISES NPR 9 SWADESHI VASTRA BIKRI BHA NPR 10 UNNAT INDUSTRIES LTD. NPR 11 RAJ PHOTO STUDIO NPR 12 RND ENTERPRISES NPR 13 LUMBINI RESORT AND HILL D NPR 14 ARUNODAY POLYPACK IND. NPR 15 UNNAT INDUSTRIES PVT.LTD. NPR 16 KRISHNA MODERN DAL UDYOG NPR 17 TIRUPATI DISTRIB. CONCERN NPR 18 LAXMI GALLA KATTA KHARID NPR 19 URGN HARDWARE CONCERN. NPR 20 AASHMA COOPERATIVE FINANC NPR 21 VERITY PRINTERS(P)LT NPR 22 PUZA TRADERS NPR 23 NEPAL MATCH MANUFACTURER NPR 24 G.B TEXTILE MILLS PVT. LT NPR 25 VISION 9PRODUCT. (P) L.-R NPR 26 PHOOLPATI ENTERPRISES NPR 27 ROSHI SAVING & CREDIT CO. NPR 28 SHRESTHA TRD.GROUP P.LTD. NPR 29 P.D.CONSULT (PARTNERS FOR NPR 30 N.Y.S.M.S RELIEF FUND NPR 31 ASHOK WIRE PVT. LTD NPR 32 PAWAN KRISHNA HARDWARE ST NPR 33 OCEAN COMPUTER PVT. LTD. NPR 34 CHHIGU MULTIPURPOSE CO-OP NPR 35 GAJENDRA TRADERS NPR 36 SURENDRA KARKI NPR 37 GATE WAY INT'L TRADERS NPR 38 VYAHUT COMMERCIAL TRADERS NPR 39 SAPTA KOSHI SAV.&CR. CO.L NPR 40 MHAIPI HOSIERY NPR 41 STYLE FOOTWEARS P LTD NPR 42 MINA IMPEX NPR 43 CUSTOM CLEARANCE SERVICE NPR 44 HOTEL LA DYNASY PVT.