Changes in a Southern Welsh English Accent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paul Foulkes and Gerard Docherty (Eds.), Urban Voices: Accent Studies in the British Isles

408 ENGLISH LANGUAGE AND LINGUISTICS further explanations for their contemporary distribution. Now, with Krug's results at one's ®nger tips, further research can be spear-headed grounded in his rich ®ndings. Reviewer's address: Department of Linguistics University of Toronto 130 St George Street, Room 6076 Toronto, Ontario M5S 3H1 Canada [email protected] References Facchinetti, R., M. Krug, & F. Palmer (eds.) (to appear). Modality in contemporary English. Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter. Ho¯and, K., A. Lindebjerg, & J. Thunestvedt (1999). ICAME collection of English language corpora. CD. 2nd edition. The HIT Centre. University of Bergen. Bergen, Norway. Kroch, A. S. (1989). Re¯exes of grammar in patterns of language change. Language Variation and Change 1: 199±244. Kroch, A. S. (2001). Syntactic change. In Baltin, M. & C. Collins (eds.), The handbook of contemporary syntactic theory. Malden: Blackwell Publishers. 699±729. Mair, C. & M. Hundt (1997). `Agile' and `uptight' genres: the corpus-based approach to language change in progress. Paper presented at International Conference on Historical Linguistics. DuÈsseldorf, Germany. Tagliamonte, S. A. (2001). Have to, gotta, must: grammaticalization, variation and specialization in English deontic modality. Paper presented at the Symposium on Corpus Research on Grammaticalization in English (CORGIE). Vaxjo, Sweden. 20±22 April 2001. Tagliamonte, S. A. (to appear). `Every place has a different toll': determinants of grammatical variation cross-variety perspective. In Rhodenberg G. & B. Mondorf (eds.), Determinants of grammatical variation in English. Berlin and New York: Mouton de Gruyter. (Received 3 May 2002) DOI: 10.1017/S1360674302270288 Paul Foulkes and Gerard Docherty (eds.), Urban voices: accent studies in the British Isles. -

Salient Features of the Welsh Accent That Are Chosen to Be Portrayed in Film

MA Language and Communication Research Cardiff University Salient Features of the Welsh Accent that are Chosen to be Portrayed in Film Andrew Booth C1456511 Supervisor: Dr Mercedes Durham Word Count: 16,448 September 2015 Abstract The accent portrayed by an actor in films has many different implications to the audience. For authenticity, the filmmakers need their accent to be as close to genuine speech as possible. The Welsh-English accent in film is portrayed in many different ways; the aim of this study is to investigate which features are viewed as salient to filmmakers when portraying a Welsh accent. This dissertation focuses the portrayal of salient features of the Welsh-English accent in the film Pride (2014). Pride was chosen because it can compare Welsh to non-Welsh actors who portray a Welsh-English accent. The research is carried out on the film using both auditory and acoustic analysis. Tokens from the film were coded in terms of their realisations for analysis and comparison to previous literature. This research produced a number of key findings: first, the Welsh actors supported previous research on patterns of realisation for Welsh-English. Second, the non-Welsh actors recognised and produced the key features of a Welsh-English accent. Finally, the features presented are salient when representing a Welsh accent in film. In summary, theories such as accommodation, language transference, hypercorrection, fudging and transition were used to explain variation of accents. This research argues for a multi- methodological approach to analysing different features of a Welsh-English accent in film. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank my supervisor, Dr Mercedes Durham for her instrumental advice and insight over the past few months. -

LINGUISTIC CONTEXT of H-DROPPING Heinrich RAMISCH University of Bamberg Heinrich

Dialectologia. Special issue, I (2010), 175-184. ISSN: 2013-22477 ANALYSING LINGUISTIC ATLAS DATA: THE (SOCIO-) LINGUISTIC CONTEXT OF H-DROPPING Heinrich R AMISCH University of Bamberg [email protected] Abstract This presentation will seek to illustrate how linguistic atlas data can be employed to obtain a better understanding of the mechanisms of linguistic variation and change. For this purpose, I will take a closer look at ‘H-dropping’ – a feature commonly found in various European languages and also widely used in varieties of British English. H-dropping refers to the non-realization of /h/ in initial position in stressed syllables before vowels, as for example, in hand on heart [ 'ænd ɒn 'ɑː t] or my head [m ɪ 'ɛd]. It is one of the best-known nonstandard features in British English, extremely widespread, but also heavily stigmatised and commonly regarded as ‘uneducated’, ‘sloppy’, ‘lazy’, etc. It prominently appears in descriptions of urban accents in Britain (cf. Foulkes/Docherty 1999) and according to Wells (1982: 254), it is “the single most powerful pronunciation shibboleth in England”. H-dropping has frequently been analysed in sociolinguistic studies of British English and it can indeed be regarded as a typical feature of working-class speech. Moreover, H-dropping is often cited as one of the features that differentiate ‘Estuary English’ from Cockney, with speakers of the former variety avoiding ‘to drop their aitches’. The term ‘Estuary English’ is used as a label for an intermediate variety between the most localised form of London speech (Cockney) and a standard form of pronunciation in the Greater London area. -

Envt1635-Lp-Ldp Reg of Alt Sites

Neath Port Talbot County Borough Council Local Development Plan 2011 –2026 Register of Alternative Sites January 2014 www.npt.gov.uk/ldp Contents 1 Register of Alternative Sites 1 2014) 1.1 Introduction 1 1.2 What is an Alternative Site? 1 (January 1.3 The Consultation 1 Sites 1.4 Register of Alternative Sites 3 1.5 Consequential Amendments to the LDP 3 Alternative of 1.6 What Happens Next? 4 1.7 Further Information 4 Register - LDP APPENDICES Deposit A Register of Alternative Sites 5 B Site Maps 15 PART A: New Sites 15 Afan Valley 15 Amman Valley 19 Dulais Valley 21 Neath 28 Neath Valley 37 Pontardawe 42 Port Talbot 50 Swansea Valley 68 PART B: Deleted Sites 76 Neath 76 Neath Valley 84 Pontardawe 85 Port Talbot 91 Swansea Valley 101 PART C: Amended Sites 102 Neath 102 Contents Deposit Neath Valley 106 Pontardawe 108 LDP Port Talbot 111 - Register Swansea Valley 120 of PART D: Amended Settlement Limits 121 Alternative Afan Valley 121 Amman Valley 132 Sites Dulais Valley 136 (January Neath 139 2014) Neath Valley 146 Pontardawe 157 Port Talbot 159 Swansea Valley 173 1 . Register of Alternative Sites 1 Register of Alternative Sites 2014) 1.1 Introduction 1.1.1 The Neath Port Talbot County Borough Council Deposit Local Development (January Plan (LDP) was made available for public consultation from 28th August to 15th October Sites 2013. Responses to the Deposit consultation included a number that related to site allocations shown in the LDP. Alternative 1.1.2 In accordance with the requirements of the Town and Country Planning (Local of Development Plan) (Wales) Regulations 2005(1), the Council must now advertise and consult on any site allocation representation (or Alternative Sites) received as soon as Register reasonably practicable following the close of the Deposit consultation period. -

Autumn 2019 Welcome

Wales NEWS Autumn 2019 welcome In this issue Welcome to the second 2019 edition of the Parkinson’s UK Cymru bilingual newsletter. 2 Director’s welcome This year has flown by - there is so much to celebrate it might 3 Parkinson’s drug not all fit between these pages! campaign success 4 Outpatient clinic Some really significant and innovative pieces of work, shaped saved by and with contributions from, people affected by Parkinson’s, 5 Live Loud! A project have been developed through the year including our to shout about and ‘strengthening our local work’ project in north Wales and our Newly Diagnosed Newly Diagnosed Days in south Wales. You can read more Days inside. 6 Boccia Bonkers in You can also read more about our campaign successes and Bala one of the highlights of the year - the World Parkinson’s Day 7 Strengthening our Boccia tournament - as well as some amazing fundraising local work in north stories from across Wales. Wales If you’re interested in fundraising, join us to help fund 8 Fabulous Fundraisers groundbreaking research and life-changing services for people 10 Croeso i Parkinson’s with Parkinson's. We can support your fundraising activities UK Cymru every step of the way, from a bake sale to a sing-a-thon, our 11 Wales team contacts fundraising officers and fundraising pack are at hand, full of information and advice. Contact our Fundraising team on 020 7963 3912 , email [email protected] or download your free pack from our website: www.parkinsons.org.uk/get-involved/order-fundraising- pack We always welcome your feedback on the newsletter so please do get in touch with Rachel Williams on 0344 225 3715 or email [email protected] with your views. -

A Sociolinguistic Study of T-Glottalling in Young RP: Accent, Class and Education

A Sociolinguistic Study of T-glottalling in Young RP: Accent, Class and Education Berta Badia Barrera A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy Department of Language and Linguistics University of Essex August 2015 It is impossible for an Englishman to open his mouth without making some other Englishman hate or despise him. George Bernard Shaw, Pygmalion (1916) preface Irish dramatist & socialist (1856 - 1950) 2 Table of Contents List of Tables - 6 List of Figures - 8 Acknowledgements - 10 PhD thesis abstract - 12 Introduction to the PhD thesis - 14 Chapter 1 Elite Accents of British English: Introduction to RP - 16 1.1.Why study RP sociolinguistically? - 16 1.2.The rise of accent as a social symbol in Britain: elite public boarding schools and RP - 17 1.3.What is RP and how has it been labelled? - 21 1.4 Phonological characteristics of RP and phonological innovations - 23 1.5.What is characteristic of RP and how should it be defined? - 26 1.6.Discussion on Received Pronunciation (RP): elite accents of British English - 27 Chapter 2 Literature Review - 33 2.1.What is t-glottalling and where does it come from? – 33 2.2.T-glottalling in descriptive accounts of RP - 36 2.3.T-glottalling in the South of England - 39 2.4.T-glottalling in Wales - 52 2.5.T-glottalling in Northern England - 53 2.6.T-glottalling in Scotland - 55 2.7.T-glottalling outside the UK: the United States and New Zealand - 58 2.8.Variationist studies on upper-class varieties of English - 60 2.9.Brief review on a secondary linguistic variant: tap (t) -

From "RP" to "Estuary English"

From "RP" to "Estuary English": The concept 'received' and the debate about British pronunciation standards Hamburg 1998 Author: Gudrun Parsons Beckstrasse 8 D-20357 Hamburg e-mail: [email protected] Table of Contents Foreword .................................................................................................i List of Abbreviations............................................................................... ii 0. Introduction ....................................................................................1 1. Received Pronunciation .................................................................5 1.1. The History of 'RP' ..................................................................5 1.2. The History of RP....................................................................9 1.3. Descriptions of RP ...............................................................14 1.4. Summary...............................................................................17 2. Change and Variation in RP.............................................................18 2.1. The Vowel System ................................................................18 2.1.1. Diphthongisation of Long Vowels ..................................18 2.1.2. Fronting of /!/ and Lowering of /"/................................21 2.2. The Consonant System ........................................................23 2.2.1. The Glottal Stop.............................................................23 2.2.2. Vocalisation of [#]...........................................................26 -

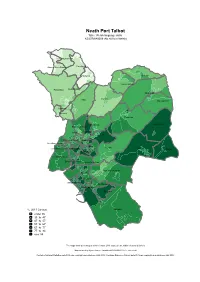

Neath Port Talbot Table: Welsh Language Skills KS207WA0009 (No Skills in Welsh)

Neath Port Talbot Table: Welsh language skills KS207WA0009 (No skills in Welsh) Lower Brynamman Cwmllynfell Gwaun−Cae−Gurwen Ystalyfera Onllwyn Seven Sisters Pontardawe Godre'r graig Glynneath Rhos Crynant Blaengwrach Trebanos Allt−wen Resolven Aberdulais Glyncorrwg Bryn−coch North Dyffryn Cadoxton Tonna Bryn−coch South Neath North Coedffranc North Cimla Pelenna Cymmer Coedffranc Central Neath East Gwynfi Neath South Coedffranc West Briton Ferry West Briton Ferry East Bryn and Cwmavon Baglan Aberavon Sandfields West Port Talbot Sandfields East Tai−bach %, 2011 Census Margam under 35 35 to 47 47 to 57 57 to 67 67 to 77 77 to 84 over 84 The maps show percentages within Census 2011 output areas, within electoral divisions Map created by Hywel Jones. Variables KS208WA0022−27 corrected Contains National Statistics data © Crown copyright and database right 2013; Contains Ordnance Survey data © Crown copyright and database right 2013 Neath Port Talbot Table: Welsh language skills KS207WA0010 (Can understand spoken Welsh only) Lower Brynamman Gwaun−Cae−Gurwen Cwmllynfell Onllwyn Ystalyfera Seven Sisters Pontardawe Godre'r graig Glynneath Rhos Crynant Blaengwrach Allt−wen Trebanos Resolven Aberdulais Bryn−coch North Glyncorrwg Dyffryn Cadoxton Tonna Coedffranc North Bryn−coch South Neath North Coedffranc Central Neath South Pelenna Gwynfi Cimla Cymmer Neath East Briton Ferry West Coedffranc West Briton Ferry East Bryn and Cwmavon Baglan Sandfields West Aberavon Port Talbot Sandfields East Tai−bach %, 2011 Census Margam under 4 4 to 5 5 to 7 7 to 9 9 to 12 12 to 14 over 14 The maps show percentages within Census 2011 output areas, within electoral divisions Map created by Hywel Jones. -

Neath Port Talbot Welsh Language Promotion Strategy

Neath Port Talbot Welsh Language Promotion Strategy This document is also available in Welsh Introduction The Welsh Language (Wales) Measure 2011, passed by the National Assembly for Wales, modernised the existing legal framework regarding the use of the Welsh language in the delivery of public services. The 2011 Measure also included: • giving the Welsh Language official status in Wales meaning that Welsh should be treated no less favourably than the English language; • establishing the role of the Welsh Language Commissioner who has responsibility for promoting the Welsh language and improving the opportunities people have to use it; • creating a procedure for introducing duties in the form of language standards that explain how organizations are expected to use the Welsh language and create rights for Welsh speakers; • making provision regarding promoting and facilitating the use of the Welsh language and increasing its use in everyday life; • making provision regarding investigating an interference with the freedom to use the Welsh language. The Measure gives the Welsh Language Commissioner authority to impose duties on a wide range of organisations to provide services in Welsh, to mainstream the language into policy development, and to develop strategies with regard to increasing the use of Welsh at work. The Welsh Language Commissioner issued Neath Port Talbot County Borough Council, along with all other local authorities in Wales, with a Compliance Notice under Section 44 of the Welsh Language (Wales) Measure 2011. The Compliance Notice contained 171 Welsh Language Standards the Council had to comply with in respect of the delivery of Welsh language services. A range of standards relating to service delivery, policy making, operational, promotion and record keeping, were applied to the Council. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Accents, attitudes and Scouse influence in North Wales English Cremer, M. Publication date 2007 Published in Toegepaste Taalwetenschap in Artikelen Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Cremer, M. (2007). Accents, attitudes and Scouse influence in North Wales English. Toegepaste Taalwetenschap in Artikelen, 77, 33-43. http://www.anela.nl/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=148#cremer General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:30 Sep 2021 ACCENTS, ATTITUDES AND SCOUSE INFLUENCE IN NORTH WALES ENGLISH M. Cremer, ACLC, Universiteit van Amsterdam 1 Introduction Regarding the sociolinguistic situation in Wales, one can say that centuries of Anglicisation brought about by political, commercial and educational forces have not only left Wales with a new language, but have also left the Welsh with an inferiority complex. -

The Acquisition of Spanish Pronunciation by Welsh Learners: Transfer from a Regional Variety of English Into Spanish

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers Faculty of Arts, Social Sciences & Humanities 1-1-2016 The acquisition of Spanish pronunciation by Welsh learners: Transfer from a regional variety of English into Spanish Alfredo Herrero de Haro University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/lhapapers Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons, and the Law Commons Recommended Citation Herrero de Haro, Alfredo, "The acquisition of Spanish pronunciation by Welsh learners: Transfer from a regional variety of English into Spanish" (2016). Faculty of Law, Humanities and the Arts - Papers. 2237. https://ro.uow.edu.au/lhapapers/2237 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] The acquisition of Spanish pronunciation by Welsh learners: Transfer from a regional variety of English into Spanish Abstract Language teachers agree that the phonetic/phonological distance between a learner’s L1 and L2 is of vital importance in mastering the sounds of the L2; however, no attention is given to the phonetic/ phonological distance between the regional variety of the speaker’s L1 and the L2. After comparing linguistic peculiarities of English, and of Welsh English in particular, with Castilian Spanish, the author proceeds to study the interlanguage of advanced students of Spanish from Wales. This helps to explain positive and negative transfer from this variety of English into Spanish and assists in producing a catalogue of the interferences to be corrected. -

The Interface Between English and the Celtic Languages

Universität Potsdam Hildegard L. C. Tristram (ed.) The Celtic Englishes IV The Interface between English and the Celtic Languages Potsdam University Press In memoriam Alan R. Thomas Contents Hildegard L.C. Tristram Inroduction .................................................................................................... 1 Alan M. Kent “Bringin’ the Dunkey Down from the Carn:” Cornu-English in Context 1549-2005 – A Provisional Analysis.................. 6 Gary German Anthroponyms as Markers of Celticity in Brittany, Cornwall and Wales................................................................. 34 Liam Mac Mathúna What’s in an Irish Name? A Study of the Personal Naming Systems of Irish and Irish English ......... 64 John M. Kirk and Jeffrey L. Kallen Irish Standard English: How Celticised? How Standardised?.................... 88 Séamus Mac Mathúna Remarks on Standardisation in Irish English, Irish and Welsh ................ 114 Kevin McCafferty Be after V-ing on the Past Grammaticalisation Path: How Far Is It after Coming? ..................................................................... 130 Ailbhe Ó Corráin On the ‘After Perfect’ in Irish and Hiberno-English................................. 152 II Contents Elvira Veselinovi How to put up with cur suas le rud and the Bidirectionality of Contact .................................................................. 173 Erich Poppe Celtic Influence on English Relative Clauses? ......................................... 191 Malcolm Williams Response to Erich Poppe’s Contribution