Anarchism in Spain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download As a PDF File

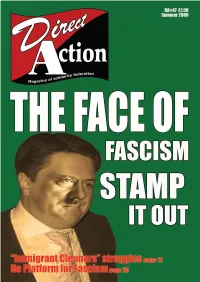

Direct Action www.direct-action.org.uk Summer 2009 Direct Action is published by the Aims of the Solidarity Federation Solidarity Federation, the British section of the International Workers he Solidarity Federation is an organi- isation in all spheres of life that conscious- Association (IWA). Tsation of workers which seeks to ly parallel those of the society we wish to destroy capitalism and the state. create; that is, organisation based on DA is edited & laid out by the DA Col- Capitalism because it exploits, oppresses mutual aid, voluntary cooperation, direct lective & printed by Clydeside Press and kills people, and wrecks the environ- democracy, and opposed to domination ([email protected]). ment for profit worldwide. The state and exploitation in all forms. We are com- Views stated in these pages are not because it can only maintain hierarchy and mitted to building a new society within necessarily those of the Direct privelege for the classes who control it and the shell of the old in both our workplaces Action Collective or the Solidarity their servants; it cannot be used to fight and the wider community. Unless we Federation. the oppression and exploitation that are organise in this way, politicians – some We do not publish contributors’ the consequences of hierarchy and source claiming to be revolutionary – will be able names. Please contact us if you want of privilege. In their place we want a socie- to exploit us for their own ends. to know more. ty based on workers’ self-management, The Solidarity Federation consists of locals solidarity, mutual aid and libertarian com- which support the formation of future rev- munism. -

Neo-Malthusianism, Anarchism and Resistance: World View and the Limits of Acceptance in Barcelona (1904-1914)

■ Article] ENTREMONS. UPF JOURNAL OF WORLD HISTORY Barcelona ﺍ Universitat Pompeu Fabra Número 4 (desembre 2012) www.entremons.org Neo-Malthusianism, Anarchism and Resistance: World View and the Limits of Acceptance in Barcelona (1904-1914) Daniel PARSONS Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona abstract This paper attempts to identify the barriers to the acceptance of Neo-Malthusian discourse among anarchists and sympathizers in the first years of the 20th century in Barcelona. Neo-Malthusian anarchists advocated the use and promotion of contraceptives and birth control as a way to achieve liberation while subscribing to a Malthusian perspective of nature. The revolutionary discourse was disseminated in Barcelona primarily by the journal Salud y Fuerza and its editor Lluis Bulffi from 1904-1914, at the same time sharing ideological goals with traditional anarchism while clashing with the conception of a beneficent and abundant nature which underpinned traditional anarchist thought. Given the cultural, social and political importance of anarchism to the history of Barcelona in particular and Europe in general, further investigation into Neo-Malthusianism and the response to the discourse is needed in order to understand better the generally accepted world-view among anarchists and how they responded to challenges to this vision. This is a topic not fully addressed by current historiography on Neo- Malthusian anarchism. This article is derived from my Master’s thesis in Contemporary History at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona entitled “Neomathusianismo, anarquismo y resistencias: Los límites de su aceptación en Cataluña”, which contains a further exposition of the ideas included herein, as well as a broader perspective on the topic. -

Vida Y Obra De Anselmo Lorenzo Federica Montseny

VIDAVIDA YY OBRAOBRA DEDE ANSELMOANSELMO LORENZOLORENZO Biblioteca Virtual OMEGALFA 2021 Vida y obra de Anselmo Lorenzo Federica Montseny Fuente: Ediciones “Espoir· 1970 Digitalización y maquetación: Demófilo 2021 Fuente de las ilustraciones incorporadas al texto: Wikipedia Libros libres para una cultura libre H ____________________________ Biblioteca Libre OMEGALFA 2021 Ω VIDA Y OBRA DE ANSELMO LORENZO El hombre y la obra b Vida y obra de Anselmo Lorenzo - 2 - Anselmo Lorenzo Vida y obra de Anselmo Lorenzo - 3 - INTRODUCCIÓN Hemos creído conveniente proceder a la tercera edición de esta obrita, porque ella es la única biografía extensa escrita sobre Anselmo Lorenzo. Nunca como ahora se ha hecho sentir tanto la necesidad de la divulgación del nombre y la obra de nuestros precursores. Cuando este volumen fue escrito, en 1938, formaba parte de unas ediciones conjuntas CNT-UGT dedicadas a ilustrar a la juventud que se iba formando en plena Guerra Civil y en plena Revolución Española. Los dos primeros volúmenes fueron de- dicados, el uno a Pablo Iglesias, escrito por Julián Zugazagoi- tia, y el otro a Anselmo Lorenzo, que se encargó a Federica Montseny. De esas primeras ediciones se hicieron muchos mi- les de ejemplares. Hoy no se encuentra ninguno en España. Y hay, en cambio, otra juventud española sedienta de conocer a los grandes teóricos del sindicalismo y sobre todo del anarco- sindicalismo que constantemente nos visita y nos asedia con demandas. De ahí quen «Espoir» haya decidido la tercera edi- ción de este volumen, que, por su precio módico y su lectura fácil, será un auxiliar precioso para el conocimiento de la figura de Lorenzo y de cuanto, en el curso de su vida ejemplar, cons- tituyó el clima social, las luchas y los empeños de su existen- cia, así como la de los miles de obreros que con él los com- partieron. -

State of Ambiguity: Civic Life and Culture in Cuba's First Republic

STATE OF AMBIGUITY STATE OF AMBIGUITY CiviC Life and CuLture in Cuba’s first repubLiC STEVEN PALMER, JOSÉ ANTONIO PIQUERAS, and AMPARO SÁNCHEZ COBOS, editors Duke university press 2014 © 2014 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-f ree paper ♾ Designed by Heather Hensley Typeset in Minion Pro by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data State of ambiguity : civic life and culture in Cuba’s first republic / Steven Palmer, José Antonio Piqueras, and Amparo Sánchez Cobos, editors. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-0-8223-5630-1 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn 978-0-8223-5638-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Cuba—History—19th century. 2. Cuba—History—20th century. 3. Cuba—Politics and government—19th century. 4. Cuba—Politics and government—20th century. 5. Cuba— Civilization—19th century. 6. Cuba—Civilization—20th century. i. Palmer, Steven Paul. ii. Piqueras Arenas, José A. (José Antonio). iii. Sánchez Cobos, Amparo. f1784.s73 2014 972.91′05—dc23 2013048700 CONTENTS Introduction: Revisiting Cuba’s First Republic | 1 Steven Palmer, José Antonio Piqueras, and Amparo Sánchez Cobos 1. A Sunken Ship, a Bronze Eagle, and the Politics of Memory: The “Social Life” of the USS Maine in Cuba (1898–1961) | 22 Marial Iglesias Utset 2. Shifting Sands of Cuban Science, 1875–1933 | 54 Steven Palmer 3. Race, Labor, and Citizenship in Cuba: A View from the Sugar District of Cienfuegos, 1886–1909 | 82 Rebecca J. Scott 4. Slaughterhouses and Milk Consumption in the “Sick Republic”: Socio- Environmental Change and Sanitary Technology in Havana, 1890–1925 | 121 Reinaldo Funes Monzote 5. -

Comissió Del Centenari De CNT (1910 - 2010) Comissió Permanent De Barcelona, CNT-Barcelona Pl

Comissió del Centenari de CNT (1910 - 2010) Comissió Permanent de Barcelona, CNT-Barcelona Pl. Duc de Medinaceli, nº 6 Entresòl 1ª, 08002 Barcelona C/ Joaquim Costa, nº 34 Baixos, 08001 Barcelona ALTERNATIVES TO CAPITALISM: SELF-MANAGEMENT IN THE SPOTLIGHT Within the framework of the CNT-AIT centenary (1910-2010), a series of conferences brought together under the name of “Alternatives to Capitalism: Self-management in the spotlight” will take place in Barcelona. These conferences will be held throughout april 2010. The contents will be organized in three blocks of lectures: theoretical, historical and a broader one, based in more current experiences. The theoretical block draws up a program of lectures on how the capitalist system works, focusing on the present moment of economic and social crisis. Anarcho-syndicalist proposals facing the crisis will also be debated. This theoretical perspective is completed with several papers which shall offer a wide vision of economic and social literature on the subject of socialism and libertarian-communism models. The historical block tries to put forward two strong models that may serve as an alternative to the capitalist system. On the one hand, that of the anarchist collectivization during the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939), for which lectures will be included to explain how it worked in the different regions where it was implemented (Catalonia, the Valencian Community, Aragon, Castile, Andalusia). On the other hand, explanations will be offered on the Yugoslav co-management model (1950-1990) with the purpose of assessing this experience both in the light of a possible model for the development of impoverished countries and from the limits imposed on socialism by the five-year plan, the market and the One Party State, along with a strictly libertarian vision of the whole process. -

Bajo Palabra Revista De Filosofía Monográfico

ISSN: 1576-3935 Depósito Legal: M-4343-2008 http://www.bajopalabra.es BAJO PALABRA REVISTA DE FILOSOFÍA MONOGRÁFICO La Violencia y sus Formas Dirigida y coordinada por la Asociación de Filosofía Bajo Palabra (AFBP) Edificio de la Facultad de Filosofía y Letras Mod. V, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid (UAM) Campus de Canto Blanco, 28049, Madrid. Telf. 600023291 E-mail: [email protected] – http://www.bajopalabra.es Editoras invitadas: Marta NOGUEROLES JOVÉ y Cristina HERMIDA DEL LLANO Publicación patrocinada por la Universidad Autónoma de Madrid a través de los siguientes órganos institucionales: Vicerrectorado de Estudiantes Vicedecanato de Estudiantes y Actividades Culturales Departamento de Antropología Social y Pensamiento Filosófico Español Departamento de Filosofía BAJO PALABRA. Revista de Filosofía II Época, Nº 15 (2017) ISSN: 1576-3935 Depósito Legal: M-4343-2008 http://www.bajopalabra.es BAJO PALABRA JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY SPECIAL ISSUE Violence and its Forms Edited and coordinated by the Bajo Palabra Philosophical Association (Asociación de Filosofía Bajo Palabra - AFBP) Address: Edificio de la Facultad de Filosofía y Letras Mod. V. Universidad Autónoma de Madrid (UAM) Campus de Canto Blanco, 28049, Madrid. Telf. 600023291 E-mail: [email protected] URL: http://www.bajopalabra.es Guest Editors: Marta NOGUEROLES JOVÉ and Cristina HERMIDA DEL LLANO A publication sponsored by the Autonomous University of Madrid in collaboration with the following institutional bodies: Vice-chancellor of Students Associate Dean of Students and Cultural Activities Department of Social Anthropology and Spanish Philosophical Thought Department of Philosophy BAJO PALABRA. Revista de Filosofía II Época, Nº 15 (2017) La revista Bajo Palabra ofrece a los autores la difusión de sus resultados de investigación principalmente a través del Portal de Revistas electrónicas de la UAM: https://revistas.uam.es/bajopalabra y de Biblos-e Archivo - Repositorio Institucional de la Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, así como a través de diferentes bases de datos, catálogos, etc. -

Vol. 35 Ha. 23 February, 1974

« 5p Vol. 35 Ha. 8 23 February, 1974 THE SOLS VIRTUE of this election question has some rather distur is its brevity. In the words bing factual answers, end the of Thomas Hcbbes (talking about bogey-stories that worked just something entirely different) it after the 1939-45 war will not is ’nasty, solitary, brutish and work again — short of a last- short’. Its nastiness is inhe minute scare-story like the rent in its cheap opportunism, Zinoviev letter or the Post- in its schoolboy slapstick; it Off ice -Savings annexation which is solitary in its complete iso worked well in the past. lation from anything connected There have been attempts tc with human life, it has its sol swing the focus of the election "I ’M SORRY, mv horny-handed o ld itary moment of truth in the onto the cost of living, this nroles--but in the National Int polling booth when one can real has driven the Conservatives to erest we must reduce vour stand- ise (usually too late) what a their refuge in the admittedly ard of living to improve out own.w farce it all is; it is brutish increased cost (and shortage) of in its frank appeals to our world food supplies. Now, as we baser instincts and its back- topics and problems it should go to press, the focus has shif cover are ignored, which is pro stage ’survival cf the fittest’ ted to the question of oil - not bably ju31 as veil for they, too. deals. of course the world shortage - are not soluble by political Its shortness was rendered but how to exploit Britain’s methods. -

Pedro Esteve (Barcelona I865-Weehauken, N. J. I925): a Catalan Anarchist in the United States Joan Casanovas L Codina

You are accessing the Digital Archive of the Esteu accedint a l'Arxiu Digital del Catalan Catalan Review Journal. Review By accessing and/or using this Digital A l’ accedir i / o utilitzar aquest Arxiu Digital, Archive, you accept and agree to abide by vostè accepta i es compromet a complir els the Terms and Conditions of Use available at termes i condicions d'ús disponibles a http://www.nacs- http://www.nacs- catalanstudies.org/catalan_review.html catalanstudies.org/catalan_review.html Catalan Review is the premier international Catalan Review és la primera revista scholarly journal devoted to all aspects of internacional dedicada a tots els aspectes de la Catalan culture. By Catalan culture is cultura catalana. Per la cultura catalana s'entén understood all manifestations of intellectual totes les manifestacions de la vida intel lectual i and artistic life produced in the Catalan artística produïda en llengua catalana o en les language or in the geographical areas where zones geogràfiques on es parla català. Catalan Catalan is spoken. Catalan Review has been Review es publica des de 1986. in publication since 1986. Pedro Esteve (Barcelona I865-Weehauken, N. J. I925): A Catalan Anarchist in the United States Joan Casanovas L Codina Catalan Review, Vol. V, number 1 (July, 1991), p. 57-77 PEDRO ESTEVE (BARCELONA r865-WEEHAUKEN, N. J. r925): A CATALAN ANARCHIST IN THE UNITED STATES JOAN CASANOV AS l CODINA PRELIMINARY NOTES' P edro Esteve was the most prominent anarchist to have corne from Spain to the U. S., where he was the editor of at least seven anarchist papers, a labor organizer and an orator in Spanish, Italian and English. -

Notes on Contributors / Remembering Roy Porter

Notes on Contributors / Remembering Roy Porter Not only was Roy Porter a brilliant scholar and a dedicated colleague, he was also a remarkable, generous and idiosyncratic individual – in fact, he was exactly the kind of person about whom Roy himself loved to write. We were all lucky that our lives were enriched by his presence. In this section, conventionally reserved for descriptions of ourselves, many of us have also added favourite memories of Roy, or moments when his influence shaped our ideas and careers. Roberta Bivins is Wellcome Lecturer in the History of Medicine at Cardiff University. The topic of her most recent book,Alternative Medicine? A Global Approach (2007), was suggested to her by Roy Porter many years ago. She is now studying the reciprocal impact of immigration and medical research/healthcare delivery in the US and UK since the Second World War. ‘As a nervous PhD student, I came to Roy via the most tenuous of connections: my American supervisor happened to know Roy’s wife. It is typical of his generosity that Roy invited me to London sight unseen, simply as a favour to his wife’s acquaintance. Dutifully, he scheduled regular lunches with me to check on my progress. Alongside the sandwiches and the inspiration, Roy offered me, in his inimitable way, a much- needed sense of belonging. One lunchtime, he dropped into his chair, grinned, and reported: “My mother has a question for you: did the royals use acupuncture?” I was surprised – but the idea that Roy’s mum knew all about my dissertation suddenly made me feel right at home in London. -

Karl Marx and the Iwma Revisited 299 Jürgen Herres

“Arise Ye Wretched of the Earth” <UN> Studies in Global Social History Editor Marcel van der Linden (International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) Editorial Board Sven Beckert (Harvard University, Cambridge, ma, usa) Dirk Hoerder (University of Arizona, Phoenix, ar, usa) Chitra Joshi (Indraprastha College, Delhi University, India) Amarjit Kaur (University of New England, Armidale, Australia) Barbara Weinstein (New York University, New York, ny, usa) volume 29 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/sgsh <UN> “Arise Ye Wretched of the Earth” The First International in a Global Perspective Edited by Fabrice Bensimon Quentin Deluermoz Jeanne Moisand leiden | boston <UN> This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the prevailing cc-by-nc License at the time of publication, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited. Cover illustration: Bannière de la Solidarité de Fayt (cover and back). Sources: Cornet Fidèle and Massart Théophile entries in Dictionnaire biographique du mouvement ouvrier en Belgique en ligne : maitron-en -ligne.univ-paris1.fr. Copyright : Bibliothèque et Archives de l’IEV – Brussels. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Bensimon, Fabrice, editor. | Deluermoz, Quentin, editor. | Moisand, Jeanne, 1978- editor. Title: “Arise ye wretched of the earth” : the First International in a global perspective / edited by Fabrice Bensimon, Quentin Deluermoz, Jeanne Moisand. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, [2018] | Series: Studies in global social history, issn 1874-6705 ; volume 29 | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2018002194 (print) | LCCN 2018004158 (ebook) | isbn 9789004335462 (E-book) | isbn 9789004335455 (hardback : alk. -

El MIL I Puig Antich Cc Creative Commons LICENCIA CREATIVE COMMONS Autoría - No Derivados - No Comer Cial 1.0

Antonio Téllez Solà El MIL i Puig Antich cc creative commons LICENCIA CREATIVE COMMONS autoría - no derivados - no comer cial 1.0 - Aquesta llicència permet copiar, distribuir, exhibir i interpretar aquest text, sempre que es compleixin les següents condicions: BY Autoría-atribució: s’haurá de respectar l’ autoria del text i de la seva traducció. Sempre es farà constar el nom de l’autor/a i el del traductor/a. A No comercial: no es pot fer servir aquest treball amb finalitats comercials. = No derivats: no es pot alterar, transformar, modificar o reconstruir aquest text. - Els termes d’aquesta llicència hauran de constar d’una manera clara per qualsevol ús o distribució del text. - Aquestes condicions es podran alterar amb el permís explícit de l’autor/a. Aquest llibre té una llicència Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivs-NonCommercial. Per a consultar les con- dicions d’aquesta llicència es pot visitar http://cr eative commons.or g/licenses/by-nd-nc/1.0/ o enviar una car ta a Creative Commons, 559 Nathan Abbot Way, Stanford, California 94305, EUA. © 2006 Virus editorial/Lallevir S.L. Antonio Téllez Solà El MIL i Puig Antich Maquetació: Virus editorial Coberta: Xavi Sellés Primera edició en castellà: març de 1994 Primera edició en català: octubre de 2006 Lallevir S.L. VIRUS editorial C/Aurora, 23 baixos 08001 Barcelona T./fax: 934413814 C/e: [email protected] http://www.viruseditorial.net Imprés a: Imprenta LUNA Muelle de la Merced, 3, 2.º izq. 48003 Bilbao T.: 944167518 Fax: 944153298 ISBN-10: 84-96044-77-7 Salvador Puig Antich ISBN-13: 978-84-96044-77-7 Depósito Legal: Índex Nota editorial . -

Without Borders Or Limits

Without Borders or Limits Without Borders or Limits: An Interdisciplinary Approach to Anarchist Studies Edited by Jorell A. Meléndez Badillo and Nathan J. Jun Without Borders or Limits: An Interdisciplinary Approach to Anarchist Studies, Edited by Jorell A. Meléndez Badillo and Nathan J. Jun This book first published 2013 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2013 by Jorell A. Meléndez Badillo and Nathan J. Jun and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-4768-2, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-4768-1 CONTENTS Acknowledgments ...................................................................................... ix Preface ........................................................................................................ xi Anarchist Studies After NAASN-III: Where Are We Going? Jesse Cohn Introduction ............................................................................................. xvii Nathan Jun and Jorell Meléndez Part One: Theory and Philosophy Chapter One ................................................................................................. 3 A Society in Revolt or Under Analysis? Investigating