Crystallography Meets Philately

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nano-Characterization of Ceramic-Metallic Interpenetrating Phase Composite Material Using Electron Crystallography

YOUNGSTOWN STATE UNIVERSITY Nano-Characterization of Ceramic-Metallic Interpenetrating Phase Composite Material using Electron Crystallography by Marjan Moro Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Engineering in the Mechanical Engineering Program Mechanical and Industrial Engineering May 2012 Nano-Characterization of Ceramic-Metallic Interpenetrating Phase Composite Material using Electron Crystallography by Marjan Moro I hereby release this thesis to the public. I understand that this thesis will be made available from the OhioLINK ETD Center and the Maag Library Circulation Desk for public access. I also authorize the University or other individuals to make copies of this thesis as needed for scholarly research. Signature: Marjan Moro, Student Date Approvals: Dr. Virgil C. Solomon, Thesis Advisor Date Dr. Matthias Zeller, Committee Member Date Dr. Timothy R. Wagner, Committee Member Date Dr. Hyun W. Kim, Committee Member Date Dr. Peter J. Kasvinsky, Dean of Graduate Studies Date i Abstract Interpenetrating phase composites (IPCs) have unique mechanical and physical proper- ties and thanks to these they could replace traditional single phase materials in numbers of applications. The most common IPCs are ceramic-metallic systems in which a duc- tile metal supports a hard ceramic making it an excellent composite material. Fireline, Inc., from Youngstown, OH manufactures such IPCs using an Al alloy-Al2O3 based ceramic-metallic composite material. This product is fabricated using a Reactive Metal Penetration (RMP) process to form two interconnected networks. Fireline products are used, among others, as refractory materials for handling of high temperature molten metals. A novel route to adding a shape memory metal phase within a ceramic matrix has been proposed. -

Sequencing As a Way of Work

Edinburgh Research Explorer A new insight into Sanger’s development of sequencing Citation for published version: Garcia-Sancho, M 2010, 'A new insight into Sanger’s development of sequencing: From proteins to DNA, 1943-77', Journal of the History of Biology, vol. 43, no. 2, pp. 265-323. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10739-009- 9184-1 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1007/s10739-009-9184-1 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Journal of the History of Biology Publisher Rights Statement: © Garcia-Sancho, M. (2010). A new insight into Sanger’s development of sequencing: From proteins to DNA, 1943-77. Journal of the History of Biology, 43(2), 265-323. 10.1007/s10739-009-9184-1 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 28. Sep. 2021 THIS IS AN ADVANCED DRAFT OF A PUBLISHED PAPER. REFERENCES AND QUOTATIONS SHOULD ALWAYS BE MADE TO THE PUBLISHED VERION, WHICH CAN BE FOUND AT: García-Sancho M. -

Cambridge's 92 Nobel Prize Winners Part 2 - 1951 to 1974: from Crick and Watson to Dorothy Hodgkin

Cambridge's 92 Nobel Prize winners part 2 - 1951 to 1974: from Crick and Watson to Dorothy Hodgkin By Cambridge News | Posted: January 18, 2016 By Adam Care The News has been rounding up all of Cambridge's 92 Nobel Laureates, celebrating over 100 years of scientific and social innovation. ADVERTISING In this installment we move from 1951 to 1974, a period which saw a host of dramatic breakthroughs, in biology, atomic science, the discovery of pulsars and theories of global trade. It's also a period which saw The Eagle pub come to national prominence and the appearance of the first female name in Cambridge University's long Nobel history. The Gender Pay Gap Sale! Shop Online to get 13.9% off From 8 - 11 March, get 13.9% off 1,000s of items, it highlights the pay gap between men & women in the UK. Shop the Gender Pay Gap Sale – now. Promoted by Oxfam 1. 1951 Ernest Walton, Trinity College: Nobel Prize in Physics, for using accelerated particles to study atomic nuclei 2. 1951 John Cockcroft, St John's / Churchill Colleges: Nobel Prize in Physics, for using accelerated particles to study atomic nuclei Walton and Cockcroft shared the 1951 physics prize after they famously 'split the atom' in Cambridge 1932, ushering in the nuclear age with their particle accelerator, the Cockcroft-Walton generator. In later years Walton returned to his native Ireland, as a fellow of Trinity College Dublin, while in 1951 Cockcroft became the first master of Churchill College, where he died 16 years later. 3. 1952 Archer Martin, Peterhouse: Nobel Prize in Chemistry, for developing partition chromatography 4. -

Anfinsen Experiments

Lecture Notes - 2 7.24/7.88J/5.48J The Protein Folding Problem Handouts: An Anfinsen paper Reading List Anfinsen Experiments The Problem of the title refers to how the amino acid sequence of a polypeptide chain determines the folded three-dimensional organization of the chain: • Does the sequence determine the structure?? • Protein Denaturation • Emergence of the Problem • Ribonuclease A • Refolding of ribonuclease in vitro. A. Protein Denaturation/Inactivation One of the features that identified proteins as distinctive polymers was 1) Unusual phase transition in semi purified proteins When exposed to relatively gentle conditions outside the range of physiological • heat • pH • salt • organic solvents, e.g. alcohols Lets consider the familiar transition I mentioned last week; • Heat denaturation; cooking the white of an egg • Acid denaturation; Milk turning sour Macroscopic changes in bulk solution; scatters visible light, increase in viscosity - white of egg: >>heat; opaque, hard; cool down; no change: Coagulation, Aggregation, precipitation, denaturation: One of the components is egg white lysozyme: activity assay; hydrolysis of bacterial cell walls: Activity remaining vs. temperature on same axes This transition: is Denaturation. These transitions were in general found to be irreversible: activity was not recovered upon cooling: Historically the study of the folding and unfolding of proteins emerged from trying to understand this unusual change of state or phase transitions. B. Emergence of the Protein Folding Problem In the period 1958-1960, the first structure of a protein molecule - myoglobin, the oxygen binding protein of muscle - was solved by John Kendrew in 1958, followed soon after by the related tetrameric red blood cell oxygen binding protein, hemoglobin, solved by Max Perutz, both of the British Medical Research Council Labs in Cambridge, U.K. -

Division of Academic Affairs Technology Fee – Project Proposal 2015

Division of Academic Affairs Technology Fee – Project Proposal 2015 Proposal Deadline: Wednesday, January 21, 2015 Project Proposal Type Instructional Technology Enhancement Project (ITEP) Focused projects proposed by an individual or small team with the intention of exploring new applications of instructional technology. ITEPs will typically be led by a faculty “principal investigator.” ITEPs are time-limited projects (up to two years in length) and allocations of Technology Fee funds to these projects are non-recurring. Project Title Crystallography Training Across the Sciences Total Amount of Funding Requested $9,100 Primary Project Coordinator Tim Royappa, Department of Chemistry Crystallography Training Across the Sciences Tim Royappa Department of Chemistry I. Project Description a. Introduction Crystallography has become an indispensable technique in the physical and life sciences. Its im- portance is demonstrated in Table 1, which outlines the chief developments in crystallography since its inception in the early 20th century. In fact, 2014 was designated as the International Year of Crystallography, and the key contributions of crystallography to a wide variety of science disciplines were celebrated across the globe. The reason that crystallography is so important is that it is the best way to elucidate the atomic structure of matter, leading to a better understanding of its physical, chemical and biological properties. Era Discovery/Advance in Crystallography Major Awards Diffraction of X-rays by crystals discovered by Paul Nobel Prize in Physics (1914) Ewald and Max von Laue; von Laue formulates the to von Laue; Nobel Prize in 1910s basics of crystallography; William L. Bragg works out Physics (1915) to Bragg and the fundamental equation of crystallography his father, William H. -

MSE 403: Ceramic Materials

MSE 403: Ceramic Materials Course description: Processing, characteristics, microstructure and properties of ceramic materials. Number of credits: 3 Course Coordinator: John McCloy Prerequisites by course: MSE 201 Prerequisites by topic: 1. Basic knowledge of thermodynamics. 2. Elementary crystallography and crystal structure. 3. Mechanical behavior of materials. Postrequisites: None Textbooks/other required 1. Carter, C.B. and Norton, M.G. Ceramic Materials Science and Engineering, materials: Springer, 2007. Course objectives: 1. Review of crystallography and crystal structure. 2. Review of structure of atoms, molecules and bonding in ceramics. 3. Discussion on structure of ceramics. 4. Effects of structure on physical properties. 5. Ceramic Phase diagrams. 6. Discussion on defects in ceramics. 7. Introduction to glass. 8. Discussion on processing of ceramics. 9. Introduction to sintering and grain growth. 10. Introduction to mechanical properties of ceramics. 11. Introduction to electrical properties of ceramics. 12. Introduction to bioceramics. 13. Introduction to magnetic ceramics. Topics covered: 1. Introduction to crystal structure and crystallography. 2. Fundamentals of structure of atoms. 3. Structure of ceramics and its influence on properties. 4. Binary and ternary phase diagrams. 5. Point defects in ceramics. 6. Glass and glass-ceramic composites. 7. Ceramics processing and sintering. 8. Mechanical properties of ceramics. 9. Electrical properties of ceramics. 10. Bio-ceramics. 11. Ceramic magnets. Expected student outcomes: 1. Knowledge of crystal structure of ceramics. 2. Knowledge of structure-property relationship in ceramics. 3. Knowledge of the defects in ceramics (Point defects). 4. Knowledge of glass and glass-ceramic composite materials. 5. Introductory knowledge on the processing of bulk ceramics. 6. Applications of ceramic materials in structural, biological and electrical components. -

Peptide Chemistry up to Its Present State

Appendix In this Appendix biographical sketches are compiled of many scientists who have made notable contributions to the development of peptide chemistry up to its present state. We have tried to consider names mainly connected with important events during the earlier periods of peptide history, but could not include all authors mentioned in the text of this book. This is particularly true for the more recent decades when the number of peptide chemists and biologists increased to such an extent that their enumeration would have gone beyond the scope of this Appendix. 250 Appendix Plate 8. Emil Abderhalden (1877-1950), Photo Plate 9. S. Akabori Leopoldina, Halle J Plate 10. Ernst Bayer Plate 11. Karel Blaha (1926-1988) Appendix 251 Plate 12. Max Brenner Plate 13. Hans Brockmann (1903-1988) Plate 14. Victor Bruckner (1900- 1980) Plate 15. Pehr V. Edman (1916- 1977) 252 Appendix Plate 16. Lyman C. Craig (1906-1974) Plate 17. Vittorio Erspamer Plate 18. Joseph S. Fruton, Biochemist and Historian Appendix 253 Plate 19. Rolf Geiger (1923-1988) Plate 20. Wolfgang Konig Plate 21. Dorothy Hodgkins Plate. 22. Franz Hofmeister (1850-1922), (Fischer, biograph. Lexikon) 254 Appendix Plate 23. The picture shows the late Professor 1.E. Jorpes (r.j and Professor V. Mutt during their favorite pastime in the archipelago on the Baltic near Stockholm Plate 24. Ephraim Katchalski (Katzir) Plate 25. Abraham Patchornik Appendix 255 Plate 26. P.G. Katsoyannis Plate 27. George W. Kenner (1922-1978) Plate 28. Edger Lederer (1908- 1988) Plate 29. Hennann Leuchs (1879-1945) 256 Appendix Plate 30. Choh Hao Li (1913-1987) Plate 31. -

The Early Years-Across the Bench from Bruce (1963-1966)

The Early Years—Across the Bench From Bruce (1963–1966) The Early Years—Across the Bench From Bruce (1963–1966) Garland R. Marshall1,2 1Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biophysics, Center for Computational Biology, Washington University, St. Louis, MO 63110 2Department of Biomedical Engineering, Center for Computational Biology, Washington University, St. Louis, MO 63110 Received 14 July 2007; revised 20 September 2007; accepted 5 October 2007 Published online 16 October 2007 in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com). DOI 10.1002/bip.20870 a Nobel Laureate, Chairman of the Department of Biology at ABSTRACT: Caltech and a member of the National Academy of Science, and was still willing to recommend me for graduate studies This personal reflection on the author’s experience as at Rockefeller. Bruce Merrifield’s first graduate student has been I was convinced at the time that I was chosen to study adapted from a talk given at the Merrifield Memorial neurophysiology, having failed miserably to isolate the acetyl- Symposium at the Rockefeller University on November choline receptor from denervated rabbit muscle as an under- graduate at Caltech. The outstanding neurophysiologists at 13, 2006. # 2007 Wiley Periodicals, Inc. Biopolymers Rockefeller including H. Keffer Hartline, Nobel Laureate, (Pept Sci) 90: 190–199, 2008. were more interested, however, in the wiring diagrams of the Keywords: solid phase synthesis; Merrifield; DNA synthe- eye of the horseshoe crab2 than in how a small molecule sis; combinatorial chemistry could trigger the action potential. Thus, my first laboratory experience at Rockefeller was with Prof. Henry Kunkel, a This article was originally published online as an accepted prominent immunologist.3 Prof. -

Crystal Vision Dorothy Hodgkin & the Nobel Prize “Few Were Her Equal in Generosity of Spirit, Breadth of Mind, Cultivated Humaneness, Or Gift for Giving

Crystal Vision Dorothy Hodgkin & the Nobel Prize “Few were her equal in generosity of spirit, breadth of mind, cultivated humaneness, or gift for giving. She should be remembered not only for a lifetime’s succession of brilliantly achieved structures. While those who knew her, experienced her quiet and modest and extremely powerful influence, learned from her more than the positioning of atoms in the three-dimensional molecule, she will be remembered not only with respect, and reverence, and gratitude, but more than anything else, with love. Let that be her lasting memorial.” Anne Sayre, in the Autumn 1995 Newsletter of the American Crystallographic Association Cover image © Emilio Segre Visual Archives/American Institute of Physics/Science Photo Library Letter from the Principal Dr Alice Prochaska, Somerville College Many remarkable woman scientists have passed through Somerville, but few rival Dorothy Hodgkin, whose path-breaking work in crystallography showed a mind not only attuned to high science but one also able to envision a crystal structure from the pattern made by its X-ray diffraction. Her ability to ‘see’ molecules such as cholesterol, penicillin, vitamin B and insulin transformed her field. 2014 sees the fiftieth anniversary of Professor Hodgkin’s Nobel prize. It is also the International Year of Crystallography, marking the 100th anniversary of Max von Laue’s Nobel Prize for Physics, awarded for his discovery that X-rays could be diffracted by crystals. That discovery underpinned Dorothy Hodgkin’s work. We are proud that Somerville supported her at a time when there was widespread opposition to married women pursuing academic careers. -

Basic Crystallography – Data Collection and Processing

Basic Crystallography – Data collection and processing Louise N. Dawe, PhD Wilfrid Laurier University Department of Chemistry and Biochemistry References and Additional Resources Faculty of Science, Bijvoet Center for Biomolecular Research, Crystal and Structural Chemistry. ‘Interpretation of Crystal Structure Determinations’ 2005 Course Notes: http://www.cryst.chem.uu.nl/huub/notesweb.pdf The University of Oklahoma: Chemical Crystallography Lab. Crystallography Notes and Manuals. http://xrayweb.chem.ou.edu/notes/index.html Müller, P. Crystallographic Reviews, 2009, 15(1), 57-83. Müller, Peter. 5.069 Crystal Structure Analysis, Spring 2010. (Massachusetts Institute of Technology: MIT OpenCourseWare), http://ocw.mit.edu/courses/chemistry/5- 069-crystal-structure-analysis-spring-2010/. License: Creative Commons BY-NC-SA X-ray Crystallography Data Collection and Processing • Select and mount the crystal. • Center the crystal to the center of the goniometer circles (instrument maintenance.) • Collect several images; index the diffraction spots; refine the cell parameters; check for higher metric symmetry • Determine data collection strategy; collect data. • Reduce the data by applying background, profile (spot- shape), Lorentz, polarization and scaling corrections. • Determine precise cell parameters. • Collect appropriate information for an absorption correction. (Index the faces of the crystal. A highly redundant set of data is sufficient for an empirical absorption correction.) • Apply an absorption correction to the data. (http://xrayweb.chem.ou.edu/notes/collect.html) Single crystal diffraction of X-rays Principle quantum number n = 1 K level Note: The non SI unit Å is normally used. n = 2 L level 1 Å = 10-10 m n = 3 M level etc… L to K transitions produce 'Ka' emission M to K transitions produce 'Kb' emission. -

Structure Determination by X-Ray Crystallography

Chem 406: Biophysical Chemistry Lecture 7: Structure Determination by X-ray Crystallography I. Introduction A. Most of the structures in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) were determined by x-ray diffraction. 1. PDB Statistics 2. Other names for x-ray diffraction a. x-ray crystallography b. crystallography B. In the past couple of years there has been a growing number of structures, particularly of small proteins and peptides, that have been solved using a combination nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and computational chemistry. 1. PDB Statistics C. The structural information obtained from these techniques are the coordinates of the atoms in the molecule. Overhead 1 (Print out of a PDB file) II. Image magnification A. We will look first at techniques that determine structures by producing images; these include light microscopy, electron microscopy and X-ray crystallography; first, though, we need to look into the properties of light. B. Light 1. The wavelike nature of light (electromagnetic radiation) a. Light waves are depicted as having oscillating electric and magnetic field components that are at right angles to one another. b. These waves are described using the following parameters. Overhead 2 and on board ( a light wave) i. wavelength () ii. frequency ( = c/) iii. Energy (E = h) 1. The constant h, is Planck’s constant and is equal to 6.63 x 10-34 Js (Joule-seconds). 2. Light scattering and refraction a. When light passes through matter the oscillating electrical field polarizes the atoms present in the matter. i. Remember that atoms are made of a nucleus containing positively charged protons and is surrounded by negatively charged electrons. -

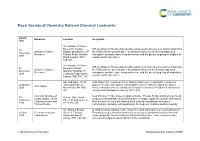

RSC Branding

Royal Society of Chemistry National Chemical Landmarks Award Honouree Location Inscription Date The Institute of Cancer Research, Chester ICR scientists on this site and elsewhere pioneered numerous new cancer drugs from 10 Institute of Cancer Beatty Laboratories, 237 the 1950s until the present day – including the discovery of chemotherapy drug December Research Fulham Road, Chelsea carboplatin, prostate cancer drug abiraterone and the genetic targeting of olaparib for 2018 Road, London, SW3 ovarian and breast cancer. 6JB, UK The Institute of Cancer ICR scientists on this site and elsewhere pioneered numerous new cancer drugs from 10 Research, Royal Institute of Cancer the 1950s until the present day – including the discovery of chemotherapy drug December Marsden Hospital, 15 Research carboplatin, prostate cancer drug abiraterone and the genetic targeting of olaparib for 2018 Cotswold Road, Sutton, ovarian and breast cancer. London, SM2 5NG, UK Ape and Apple, 28-30 John Dalton Street was opened in 1846 by Manchester Corporation in honour of 26 October John Dalton Street, famous chemist, John Dalton, who in Manchester in 1803 developed the Atomic John Dalton 2016 Manchester, M2 6HQ, Theory which became the foundation of modern chemistry. President of Manchester UK Literary and Philosophical Society 1816-1844. Chemical structure of Near this site in 1903, James Colquhoun Irvine, Thomas Purdie and their team found 30 College Gate, North simple sugars, James a way to understand the chemical structure of simple sugars like glucose and lactose. September Street, St Andrews, Fife, Colquhoun Irvine and Over the next 18 years this allowed them to lay the foundations of modern 2016 KY16 9AJ, UK Thomas Purdie carbohydrate chemistry, with implications for medicine, nutrition and biochemistry.