The End of Sixty Years Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Care Label Recommendations

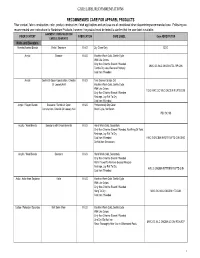

CARE LABEL RECOMMENDATIONS RECOMMENDED CARE FOR APPAREL PRODUCTS Fiber content, fabric construction, color, product construction, finish applications and end use are all considered when determining recommended care. Following are recommended care instructions for Nordstrom Products, however; the product must be tested to confirm that the care label is suitable. GARMENT/ CONSTRUCTION/ FIBER CONTENT FABRICATION CARE LABEL Care ABREVIATION EMBELLISHMENTS Knits and Sweaters Acetate/Acetate Blends Knits / Sweaters K & S Dry Clean Only DCO Acrylic Sweater K & S Machine Wash Cold, Gentle Cycle With Like Colors Only Non-Chlorine Bleach If Needed MWC GC WLC ONCBIN TDL RP CIIN Tumble Dry Low, Remove Promptly Cool Iron If Needed Acrylic Gentle Or Open Construction, Chenille K & S Turn Garment Inside Out Or Loosely Knit Machine Wash Cold, Gentle Cycle With Like Colors TGIO MWC GC WLC ONCBIN R LFTD CIIN Only Non-Chlorine Bleach If Needed Reshape, Lay Flat To Dry Cool Iron If Needed Acrylic / Rayon Blends Sweaters / Gentle Or Open K & S Professionally Dry Clean Construction, Chenille Or Loosely Knit Short Cycle, No Steam PDC SC NS Acrylic / Wool Blends Sweaters with Embelishments K & S Hand Wash Cold, Separately Only Non-Chlorine Bleach If Needed, No Wring Or Twist Reshape, Lay Flat To Dry Cool Iron If Needed HWC S ONCBIN NWOT R LFTD CIIN DNID Do Not Iron Decoration Acrylic / Wool Blends Sweaters K & S Hand Wash Cold, Separately Only Non-Chlorine Bleach If Needed Roll In Towel To Remove Excess Moisture Reshape, Lay Flat To Dry HWC S ONCBIN RITTREM -

Natural Materials for the Textile Industry Alain Stout

English by Alain Stout For the Textile Industry Natural Materials for the Textile Industry Alain Stout Compiled and created by: Alain Stout in 2015 Official E-Book: 10-3-3016 Website: www.TakodaBrand.com Social Media: @TakodaBrand Location: Rotterdam, Holland Sources: www.wikipedia.com www.sensiseeds.nl Translated by: Microsoft Translator via http://www.bing.com/translator Natural Materials for the Textile Industry Alain Stout Table of Contents For Word .............................................................................................................................. 5 Textile in General ................................................................................................................. 7 Manufacture ....................................................................................................................... 8 History ................................................................................................................................ 9 Raw materials .................................................................................................................... 9 Techniques ......................................................................................................................... 9 Applications ...................................................................................................................... 10 Textile trade in Netherlands and Belgium .................................................................... 11 Textile industry ................................................................................................................... -

Choosing the Proper Short Cut Fiber for Your Nonwoven Web

Choosing The Proper Short Cut Fiber for Your Nonwoven Web ABSTRACT You have decided that your web needs a synthetic fiber. There are three important factors that have to be considered: generic type, diameter, and length. In order to make the right choice, it is important to know the chemical and physical characteristics of the numerous man-made fibers, and to understand what is meant by terms such as denier and denier per filament (dpf). PROPERTIES Denier Denier is a property that varies depending on the fiber type. It is defined as the weight in grams of 9,000 meters of fiber. The current standard of denier is 0.05 grams per 450 meters. Yarn is usually made up of numerous filaments. The denier of the yarn divided by its number of filaments is the denier per filament (dpf). Thus, denier per filament is a method of expressing the diameter of a fiber. Obviously, the smaller the denier per filament, the more filaments there are in the yarn. If a fairly closed, tight web is desired, then lower dpf fibers (1.5 or 3.0) are preferred. On the other hand, if high porosity is desired in the web, a larger dpf fiber - perhaps 6.0 or 12.0 - should be chosen. Here are the formulas for converting denier into microns, mils, or decitex: Diameter in microns = 11.89 x (denier / density in grams per milliliter)½ Diameter in mils = diameter in microns x .03937 Decitex = denier x 1.1 The following chart may be helpful. Our stock fibers are listed along with their density and the diameter in denier, micron, mils, and decitex for each: Diameter Generic Type -

Yarn Numbering Systems

TECHNICAL BULLETIN 6399 Weston Parkway, Cary, North Carolina, 27513 • Telephone (919) 678-2220 TRI 1014 YARN NUMBERING SYSTEMS © 2003 Cotton Incorporated. All rights reserved; America’s Cotton Producers and Importers. TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION 1 DIRECT SYSTEMS 1 INDIRECT SYSTEMS 2 CONVERSION 4 PLIED YARNS 4 YARN DIAMETER 5 YARN NUMBERING SYSTEMS - TABLE 1 6 CONVERSION FACTORS - TABLE 2 7 YARN NUMBERING SYSTEMS INTRODUCTION Textiles are often sold on a weight basis and consequently it is natural to express the size of "thickness" of a yarn in terms of weight (or mass). There are two basic ways in which this may be done. These are: (a) by saying how much a given length of yarn weighs, or (b) by saying what length of yarn one would have in a given weight. Generally these are known as the direct and indirect systems of yarn numbering, respectively. In other words: Weight(or mass) Direct yarn number = Length Length Indirect yarn number = Weight(or mass) It will be noted that one is the inverse of the other. In the first case, the number gets larger as the yarn or strand gets coarser. In the second case, the number gets smaller as the yarn or strand gets coarser. Each system has its advantages and disadvantages and each has found areas in which, by custom, it is used. It so happens that because long, thin strands are usually involved, the length figures are usually large and the weight figures are small. Consequently, the yarn numbers would get impossibly large or impossibly small unless special units are used. -

Investigation of the Mechanical Properties of a Carbon Fibre-Reinforced Nylon Filament for 3D Printing

machines Article Investigation of the Mechanical Properties of a Carbon Fibre-Reinforced Nylon Filament for 3D Printing Flaviana Calignano 1,* , Massimo Lorusso 2 , Ignanio Roppolo 3 and Paolo Minetola 1 1 Department of Management and Production Engineering, Politecnico di Torino, Corso Duca degli Abruzzi 24, 10129 Turin, Italy; [email protected] 2 Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia, Center for Sustainable Future Technologies IIT@Polito, Corso Trento 21, 10129 Turin, Italy; [email protected] 3 Department of Applied Science and Technology, Politecnico di Torino, Corso Duca degli Abruzzi 24, 10129 Turin, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: fl[email protected]; Tel.: +39-011-090-7218 Received: 19 July 2020; Accepted: 2 September 2020; Published: 4 September 2020 Abstract: Additive manufacturing (i.e., 3D printing) has rapidly developed in recent years. In the recent past, many researchers have highlighted the development of in-house filaments for fused filament fabrication (FFF), which can extend the corresponding field of application. Due to the limited mechanical properties and deficient functionality of printed polymer parts, there is a need to develop printable polymer composites that exhibit high performance. This study analyses the actual mechanical characteristics of parts fabricated with a low-cost printer from a carbon fibre-reinforced nylon filament. The results show that the obtained values differ considerably from the values presented in the datasheets of various filament suppliers. Moreover, the hardness and tensile strength are influenced by the building direction, the infill percentage, and the thermal stresses, whereas the resilience is affected only by the building direction. Furthermore, the relationship between the mechanical properties and the filling factor is not linear. -

Analysis of the Polyester Clothing Value Chain to Identify Key Intervention Points for Sustainability Cristina Palacios‑Mateo* , Yvonne Van Der Meer and Gunnar Seide

Palacios‑Mateo et al. Environ Sci Eur (2021) 33:2 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302‑020‑00447‑x REVIEW Open Access Analysis of the polyester clothing value chain to identify key intervention points for sustainability Cristina Palacios‑Mateo* , Yvonne van der Meer and Gunnar Seide Abstract Clothing is one of the primary human needs, and the demand is met by the global production of thousands of tons of textile fbers, fabrics and garments every day. Polyester clothing manufactured from oil‑based polyethylene tereph‑ thalate (PET) is the market leader. Conventional PET creates pollution along its entire value chain—during the produc‑ tion, use and end‑of‑life phases—and also contributes to the unsustainable depletion of resources. The consumption of PET garments thus compromises the quality of land, water and air, destroys ecosystems, and endangers human health. In this article, we discuss the diferent stages of the value chain for polyester clothing from the perspective of sustainability, describing current environmental challenges such as pollution from textile factory wastewater, and microfbers released from clothing during the laundry cycle. We also consider potential solutions such as enhanced reuse and recycling. Finally, we propose a series of recommendations that should be applied to polyester clothing at all stages along the value chain, ofering the potential for meaningful and efective change to improve the environ‑ mental sustainability of polyester textiles on a global scale. Keywords: PET, Textiles, Value chain, Environmental sustainability, Microfbers, Pollution, Recycling, Life cycle Introduction with 2019 estimates in Germany suggesting an average Te global volume of fber production for textile manu- lifetime of only 4.4 years [5]. -

Textile Printing

TECHNICAL BULLETIN 6399 Weston Parkway, Cary, North Carolina, 27513 • Telephone (919) 678-2220 ISP 1004 TEXTILE PRINTING This report is sponsored by the Importer Support Program and written to address the technical needs of product sourcers. © 2003 Cotton Incorporated. All rights reserved; America’s Cotton Producers and Importers. INTRODUCTION The desire of adding color and design to textile materials is almost as old as mankind. Early civilizations used color and design to distinguish themselves and to set themselves apart from others. Textile printing is the most important and versatile of the techniques used to add design, color, and specialty to textile fabrics. It can be thought of as the coloring technique that combines art, engineering, and dyeing technology to produce textile product images that had previously only existed in the imagination of the textile designer. Textile printing can realistically be considered localized dyeing. In ancient times, man sought these designs and images mainly for clothing or apparel, but in today’s marketplace, textile printing is important for upholstery, domestics (sheets, towels, draperies), floor coverings, and numerous other uses. The exact origin of textile printing is difficult to determine. However, a number of early civilizations developed various techniques for imparting color and design to textile garments. Batik is a modern art form for developing unique dyed patterns on textile fabrics very similar to textile printing. Batik is characterized by unique patterns and color combinations as well as the appearance of fracture lines due to the cracking of the wax during the dyeing process. Batik is derived from the Japanese term, “Ambatik,” which means “dabbing,” “writing,” or “drawing.” In Egypt, records from 23-79 AD describe a hot wax technique similar to batik. -

Nylon Wool Fiber Columns

U.S. Corporate Headquarters Polysciences Europe GmbH Polysciences Asia-Pacific, Inc. 400 Valley Rd. Badener Str. 13 2F-1, 207 DunHua N. Rd. Warrington, PA 18976 69493 Hirschberg an der Taipei, Taiwan 10595 1(800) 523-2575 / (215) 343-6484 Bergstrasse, Germany (886) 2 8712 0600 1(800)343-3291 fax +(49) 6201 845 20 0 (886) 2 8712 2677 fax [email protected] +(49) 6201 845 20 20 fax [email protected] [email protected] TECHNICAL DATA SHEET 425A Page 1 of 2 Nylon Wool Fiber Columns BACKGROUND NYLON WOOL FIBER VS. SHEEP RBC ROSETTING METHODS Researchers have been using nylon wool fiber procedures to separate T-cell and Wong and Mittal (1981)9 did extensive research comparing the methods of Nylon B-cell lymphocytes for more than 20 years. In the early 1970’s M. H. Julius et al Wool Fiber separation and the commonly- used and well-studied sheep RBC (1973),1 Eisen et al (1972),2 and Greaves & Brain (1974)3 described specific (SRBC) rosetting.10,11 Wong and Mittal were interested in isolating B-cells for conditions for the use of Nylon Wool Fiber in columns or plastic straws. These serologic typing of HLA-DR antigen. protocols resulted in yields of 50-90% T-cell recovery and 10-100 fold B-cell depletion. Wong and Mittal concluded that “Due to its simplicity and reliability, nylon wool adherence may be preferred over the SRBC rosette method for the routine pheno- These early researchers found it necessary to scrub or wash their Nylon Wool Fiber typing of B-cells.” Their findings are illustrated in Table 1. -

Technical Product Guide

strength in materials Technical Product Guide www.agy.com Table of Contents Corporate Overview AGY provides the best quality, highest performance, and broadest range of glass fiber yarns, rovings and chop products to Corporate Overview .............................1 a wide variety of markets and end uses. Although founded as an independent entity Glass Fiber Manufacturing ...................2 in 1998, AGY has a 50+ year history of serving the composites industry. Nomenclature ......................................3 Globally, AGY has over 600 employees Conversion Tables ...............................6 involved in production, sales, distribution and development of our products. Our AGY Glass Yarns .................................8 world headquarters, technology center and manufacturing facility are located in Aiken, AGY Glass Rovings ...........................14 SC U.S.A. AGY Chopped Glass ..........................16 We also have commercial and administrative offices in Lyon, France, and AGY Packaging Specificaions ............18 a commercial office in Shanghai, China. AGY Sizing Systems ..........................20 Typical Fiber Properties .....................26 Glossary of Terms ..............................28 strength in materials 1 Glass Fiber Manufacturing Glass Fiber Nomenclature AGY glass fibers are made from molten glass. The viscous liquid is General drawn through tiny holes at the base of the furnace to form hair-like Glass fiber yarns are typically identified by either an inch-pound based system (U.S. customary system) or a TEX/metric system (based on the SI*/metric system). filaments. A protective sizing, applied as the filament cools and This section gives a brief description of glass fiber yarn nomenclature, including hardens, helps prevent abrasion during additional processing and comparisons of the two systems (see table on page 4). A more comprehensive makes the glass compatible with various resin systems. -

DID YOU KNOW? PET (Polyethylene Terephthalate) Is Actually Polyester. When PET Is Used for Bottles, Containers and Other

355 Lexington Ave., Suite 1500 ▪ New York, NY 10017 ▪ www.PETresin.org DID YOU KNOW? Little-Known Facts about PET Plastic . PET (polyethylene terephthalate) is actually polyester. When PET is used for bottles, containers and other applications, it is called PET or PET resin. When PET is used as a fiber, it is typically called polyester. The PET bottle was invented by Nathaniel C. Wyeth, a DuPont engineer and brother of American painter Andrew Wyeth. The patent was issued to Wyeth in 1973 and assigned to DuPont. According to the EPA, recycling one pound of PET bottles (that’s about 10 two-liter soda bottles) saves approximately 26,000 BTUs of energy. PET bottles and the sun are helping millions of people in developing countries obtain potable water. Using a system called SODIS (solar water disinfection), inhabitants set water-filled PET bottles in the sun for several hours or days – depending on how much sunlight is available – as a simple but effective means of destroying disease-causing bacteria and gaining safe drinking water. More than 1.5 billion pounds of used PET bottles and containers are collected in the U.S. each year for recycling. PET is the most recycled plastic in the U.S. and the world. A single-serve PET bottle (0.5 liter) is strong enough to hold 50 times its weight in water. Chemists keep finding new ways to make PET lighter without losing any strength. A 2-liter PET bottle that weighed 68 grams in 1980 now weighs as little as 42 grams. The average weight of single-serve 0.5 liter PET water bottle is now 9.9 grams, nearly half of what it weighed in 2000. -

Handle and Comfort Characteristics of Cotton Core Spun Lycra and Polyester/ Lycra Fabrics for Application As Blouse Nirmala Varghese and G

Volume 8, Issue 4, Spring2014 Handle and Comfort Characteristics of Cotton Core Spun Lycra and Polyester/ Lycra Fabrics for Application as Blouse Nirmala Varghese and G. Thilagavathi Department of Apparel & Fashion Technology PSG College of Technology Tamil Nadu, India ABSTRACT Stretchable plain woven fabrics are developed with 60s cotton core spun Lycra and polyester Lycra twisted yarn (91D) in weft with cotton, silk and polyester in warp. The influence of fabric specifications on thermal comfort, low stress mechanical properties, primary and total hand value is analyzed. The results indicated that cotton core spun Lycra woven with polyester warp provided higher value of thermal conductivity, air permeability and water vapor permeability. The woven stretch fabrics produced with polyester warp, cotton core spun Lycra and polyester Lycra in weft has excellent aesthetic and drape properties. These fabrics have higher tensile resilience, tensile strain, lower shear rigidity, superior primary hand and a higher total hand value of 4.08 and 3.93 respectively and are best suitable for women’s blouse. Keywords: Cotton core spun Lycra, polyester/Lycra, woven stretch, fabric handle, sari blouse Introduction Lycra and polyester/lycra twisted yarn. Several studies have been carried out Stretch is often the most important investigating the physical properties of core property of textiles that contribute to wearer spun yarn, cotton/lycra and properties of the comfort. The stretch yarn and fabrics are fabrics containing different rates of spandex widely used and preferred by the people in yarns. Core spun cotton/spandex shows high the last few years all over the world because resiliency property than 100% cotton yarns, of their stretch ability and shape retention due to its soft and rubbery isocyanate properties. -

Interfacial Adhesion in Rayon/Nylon Sheath/Core Composite Fibers. Weiying Tao Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1991 Interfacial Adhesion in Rayon/Nylon Sheath/Core Composite Fibers. Weiying Tao Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Tao, Weiying, "Interfacial Adhesion in Rayon/Nylon Sheath/Core Composite Fibers." (1991). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 5213. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/5213 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand corner and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps.