Reduced Human Suffering in Conflict-Affected Areas A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coi Chronology

COI CHRONOLOGY Country of Origin ARMENIA, AZERBAIJAN Main subject The course of the Nagorno-Karabakh armed conflict and its impact on the civilian population Date of completion 10 November 2020 Disclaimer This chronology note has been elaborated according to the EASO COI Report Methodology and EASO Writing and Referencing Guide. The information provided in this chronology has been researched, evaluated and processed with utmost care within a limited time frame. All sources used are referenced. A quality review has been performed in line with the above mentioned methodology. This document does not claim to be exhaustive neither conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to international protection. If a certain event, person or organisation is not mentioned in the report, this does not mean that the event has not taken place or that the person or organisation does not exist. Terminology used should not be regarded as indicative of a particular legal position. The information in this chronology does not necessarily reflect the opinion of EASO and makes no political statement whatsoever. The target audience is caseworkers, COI researchers, policy makers, and asylum decision-making authorities. The chronology was finalised on 10 November 2020 and will be updated according to the development of the situation in the region. COI CHRONOLOGY Background Nagorno-Karabakh is a mountainous landlocked region within the borders of Azerbaijan1 and is mainly inhabited by ethnic Armenians.2 Recognized under international law as a part of Azerbaijan, -

General Assembly Security Council Seventieth Session Seventy-First Year Agenda Items 35 and 40

United Nations A/70/1034–S/2016/767 General Assembly Distr.: General 8 September 2016 Security Council Original: English General Assembly Security Council Seventieth session Seventy-first year Agenda items 35 and 40 Protracted conflicts in the GUAM area and their implications for international peace, security and development The situation in the occupied territories of Azerbaijan Letter dated 6 September 2016 from the Permanent Representative of Azerbaijan to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General Upon instructions from my Government, I have the honour to convey herewith the records of the violations of the ceasefire by the Republic of Armenia in July 2016 (see annex).* During the period in question, Armenia violated the ceasefire regime 345 times and continued the usage of large-calibre guns and heavy weaponry from its positions in the occupied territories of the Republic of Azerbaijan and from its own territory. The continuous occupation of a large part of the territory of the Republic of Azerbaijan by the armed forces of Armenia remains the main obstacle to the settlement of the conflict and the only source of the escalation of the situation on the front line and of occurrences of hostilities and casualties. The sooner the Republic of Armenia withdraws its troops from the occupied territories of the Republic of Azerbaijan, the sooner peace and stability can be restored in the region. I should be grateful if you would have the present letter and its annex circulated as a document of the General Assembly, under agenda items 35 and 40, and of the Security Council. -

Forced Displacement in the Nagorny Karabakh Conflict: Return and Its Alternatives

Forced displacement in the Nagorny Karabakh conflict: return and its alternatives August 2011 conciliation resources Place-names in the Nagorny Karabakh conflict are contested. Place-names within Nagorny Karabakh itself have been contested throughout the conflict. Place-names in the adjacent occupied territories have become increasingly contested over time in some, but not all (and not official), Armenian sources. Contributors have used their preferred terms without editorial restrictions. Variant spellings of the same name (e.g., Nagorny Karabakh vs Nagorno-Karabakh, Sumgait vs Sumqayit) have also been used in this publication according to authors’ preferences. Terminology used in the contributors’ biographies reflects their choices, not those of Conciliation Resources or the European Union. For the map at the end of the publication, Conciliation Resources has used the place-names current in 1988; where appropriate, alternative names are given in brackets in the text at first usage. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of Conciliation Resources or the European Union. Altered street sign in Shusha (known as Shushi to Armenians). Source: bbcrussian.com Contents Executive summary and introduction to the Karabakh Contact Group 5 The Contact Group papers 1 Return and its alternatives: international law, norms and practices, and dilemmas of ethnocratic power, implementation, justice and development 7 Gerard Toal 2 Return and its alternatives: perspectives -

E718 March 1, 2003

E718 March 1, 2003 REPUBLIC OF AZERBAIJAN STATE AMELIORATION AND IRRIGATION COMMITTEE Public Disclosure Authorized Attached to the Cabinet of Ministers INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION Public Disclosure Authorized IRRIGATION DISTRIBUTION SYSTEM AND MANAGEMENT IMPROVEMENT PROJECT Public Disclosure Authorized ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT AND MONITORING PLAN United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation FINAL DRAFT March 1, 2003 Public Disclosure Authorized 01/03/03 IRRIGATION DISTRIBUTION SYSTEM AND MANAGEMENT IMPROVEMENT PROJECT ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT AND MONITORING PLAN 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background 1.2 Objective 1.3 World Bank Safeguard Policies 1.4 Methodology 1.5 Consultation Process 2. ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY, LEGAL & INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK 2.1 Policy Context 2.2 Legal/Regulatory Framework for Environmental Management/Assessment 2.3 Institutional Framework for Environmental Management and Assessment 3. KEY NATURAL AND SOCIO-ECONOMIC PARAMETERS OF AZERBAIJAN 3.1 Natural Setting 3.2 Socio-Economic Factors Associated with Water Management and Irrigation 4. ANALYSIS OF BASELINE CONDITIONS 4.1 Description of Project 4.2 Analysis of Project Alternatives 4.3 Description of the Physical/Biological Environment 4.4 Description of Socio-Economic Context 4.5 Description of Stakeholders and Beneficiaries 5. ASSESSMENT OF PRINCIPAL ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACTS AND PROPOSED PREVENTIVE ACTIONS AND MITIGATION MEASURES 5.1 Anticipated Positive Social and Environmental Impacts 5.2 Anticipated -

Administrative Territorial Divisions in Different Historical Periods

Administrative Department of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan P R E S I D E N T I A L L I B R A R Y TERRITORIAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE UNITS C O N T E N T I. GENERAL INFORMATION ................................................................................................................. 3 II. BAKU ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 1. General background of Baku ............................................................................................................................ 5 2. History of the city of Baku ................................................................................................................................. 7 3. Museums ........................................................................................................................................................... 16 4. Historical Monuments ...................................................................................................................................... 20 The Maiden Tower ............................................................................................................................................ 20 The Shirvanshahs’ Palace ensemble ................................................................................................................ 22 The Sabael Castle ............................................................................................................................................. -

Putting People First

REPORT Putting people first Reducing frontline tensions in Armenia and Azerbaijan, Nagorny Karabakh April 2012 Putting people first Reducing frontline tensions in Armenia and Azerbaijan, Nagorny Karabakh SAFERWORLD APRIL 2012 Acknowledgements This report is based on contributions written by Tabib Huseynov (independent consultant) and Tevan Poghosyan (ICHD), setting out Azerbaijani and Armenian perspectives on the situation in frontier districts along the international border between Armenia and Azerbaijan, and near the Line of Contact (LOC) around Nagorny Karabakh. It was edited by Craig Oliphant (Senior Advisor, Saferworld). The report has also benefited from comments and input provided by Laurence Broers (Conciliation Resources). It draws on participatory research conducted in areas near the LOC and also in the districts of Tovuz and Gazakh in Azerbaijan along its border with Armenia, and specifically the border districts in the Tavush region. The People’s Peacemaking Perspectives project The People’s Peacemaking Perspectives project is a joint initiative implemented by Conciliation Resources and Saferworld and financed under the European Commission’s Instrument for Stability. The project provides European Union institutions with analysis and recommendations based on the opinions and experiences of local people in a range of countries and regions affected by fragility and violent conflict. © Saferworld April 2012. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without full attribution. Saferworld welcomes and encourages the utilisation and dissemination of the material included in this publication. This document has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. -

PIU Director: Sabir Ahmadov TTL: Robert Wrobel Credit : USD 66.7 Mln Proc

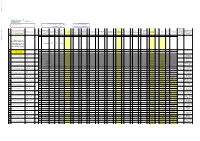

Public Disclosure Authorized C Additional Financing for IDP Revision Date: 20 Living Standards and August 2018 Livelihoods Project PIU Director: Sabir Ahmadov TTL: Robert Wrobel Credit : USD 66.7 mln Proc. Specialist: Emma Mammadkhanova Operations Officer: Nijat Veliyev PAS: Sandro Nozadze Program Assistant: Vusala Asadova Public Disclosure Authorized Contracts,Am Reception Short endments IDP Living Standards and Estimated Cost Contr. Prior / No Objection Company name Note Selection of Listing/RFP Invitation for Proposal Technical Final Contract (Amount, Actual Livelihoods Project Name Procurement Ref. # / Actual (USD) Type LS Post Ad of EOI No Objection No Objection to Sign Start Completion which is awarded # Method Expression submssion RFP Submission Evaluation Evaluation Signature Days Date and of Assignment / Contract Type- incl VAT / TB Review Contract a contract Category of Interest to the Bank Execution reason should Plan Plan / Days Interval Days Interval Days Interval Days Interval Days Interval Days Interval Days Interval Days Interval Days Interval Days Interval Days Interval be indicated Hiring the services of Public Disclosure Authorized individual consultants for A about 300 contracts for IC-1 250,000.00 IC TB Post technical supervision over contracts implementation p A- Micro-projects A P 352.49 IC Post 2/9/2017 2/9/2017 60 4/10/2017 Mammadov Local Technical Supervisor SFDI/8627-AZ/080 352.49 Public Disclosure Authorized A 352.49 IC Post 2/9/2017 2/9/2017 60 4/10/2017 Farzali Vali P 352.49 IC Post 2/9/2017 2/9/2017 60 4/10/2017 -

YOLUMUZ QARABAGADIR SON Eng.Qxd

CONTENTS Nationwide address of President Ilham Aliyev (27.09.2020) ..................4 A meeting of the Security Council chaired by President Ilham Aliyev ....9 Interview of President Ilham Aliyev in the "60 minutes" program on "Rossiya-1" TV channel ..........................................................................15 Interview of President Ilham Aliyev to Al Jazeera TV channel ..............21 Interview of President Ilham Aliyev to Al Arabiya TV channel ................35 Nationwide address of President Ilham Aliyev (04.10.2020) ..................38 Interview of President Ilham Aliyev to TRT Haber TV channel ..............51 Interview of President Ilham Aliyev to Russian "Perviy Kanal" TV ........66 Interview of President Ilham Aliyev to CNN-Tцrk Tv channel ................74 Interview of President Ilham Aliyev to Euronews TV channel ................87 Nationwide address of President Ilham Aliyev (09.10.2020) ..................92 Interview of President Ilham Aliyev to CNN International TV channel's "The Connect World" program ................................................................99 Interview of President Ilham Aliyev to Sky News TV channel ................108 Interview of President Ilham Aliyev to Russian RBC TV channel ..........116 Interview of President Ilham Aliyev to Turkish Haber Global TV channel........................................................................129 Interview of President Ilham Aliyev to Turkish Haber Turk TV channel ..........................................................................140 -

Eastern Partnership Enhancing Judicial Reform in the Eastern Partnership Countries

Eastern Partnership Enhancing Judicial Reform in the Eastern Partnership Countries Efficient Judicial Systems Report 2014 Directorate General of Human Rights and Rule of Law Strasbourg, December 2014 1 The Efficient Judicial Systems 2014 report has been prepared by: Mr Adiz Hodzic, Member of the Working Group on Evaluation of Judicial systems of the European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice (CEPEJ) Mr Frans van der Doelen, Programme Manager of the Department of the Justice System, Ministry of Security and Justice, The Netherlands, Member of the Working Group on Evaluation of Judicial systems of the CEPEJ Mr Georg Stawa, Head of the Department for Projects, Strategy and Innovation, Federal Ministry of Justice, Austria, Chair of the CEPEJ 2 Table of content Conclusions and recommendations 3 Part I: Comparing Judicial Systems: Performance, Budget and Management Chapter 1: Introduction 11 Chapter 2: Disposition time and quality 17 Chapter 3: Public budget 26 Chapter 4: Management 35 Chapter 5: Efficiency: comparing resources, workload and performance (28 indicators) 44 Armenia 46 Azerbaijan 49 Georgia 51 Republic of Moldova 55 Ukraine 58 Chapter 6: Effectiveness: scoring on international indexes on the rule of law 64 Part II: Comparing Courts: Caseflow, Productivity and Efficiency 68 Armenia 74 Azerbaijan 90 Georgia 119 Republic of Moldova 139 Ukraine 158 Part III: Policy Making Capacities 178 Annexes 185 3 Conclusions and recommendations 1. Introduction This report focuses on efficiency of courts and the judicial systems of Azerbaijan, Armenia, Georgia, the Republic of Moldova and Ukraine, commonly referred the Easter Partnership Countries (EPCs) after the Eastern Partnership Programme of the European Union. -

Refugees & Internally Displaced Persons (Idps) in the South Caucasus

REFUGEES & INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS (IDPS) IN THE SOUTH CAUCASUS: THE NUMBERS GAME KEY POINTS The South Caucasus has witnessed proportionally huge displacements of population since 1991. The region’s protracted conflicts have left large IDP communities in Azerbaijan and Georgia, which place a significant economic burden on the Azeri and Georgian governments. These communities’ right of eventual return to their homes needs to be balanced with avoiding their social marginalisation in the interim. DETAIL This paper looks at the numbers of refuges and internally-displaced persons (IDPs) currently living in the three South Caucasus states – Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia – each of which has experienced major population shifts over the last two decades as a result of territorial conflicts in the region. It also considers the politics surrounding the topic of refuges and IDPs in these three societies, as well as looking at how the region’s unrecognised entities (Abkhazia, Nagorny Karabakh and South Ossetia) deal with the concept of ‘refugees’ and ‘IDPs’ in their respective cases. Figures in each case are attached as a separate annex. The paper proceeds from the commonly-accepted definitions of the two terms, i.e.: A refugee is a person who is outside the country of their nationality and unwilling or unable to return there for fear of persecution. An IDP is a person who has been forced to flee their place of habitual residence but has not crossed an internationally-recognised state border1. Armenia Latest UNHCR figures show Armenia as hosting a registered refugee population of just over 3,000. It has no officially-registered IDPs2. -

Additions to the Decree №298

Approved by the Decree № 2475 on 31 October 2007 Additions to the Decree №298 “State Program on the Improvement of Living Conditions of Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons and Employment Promotion” of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan on 1 July 2004 ADDITIONS # Name of Activity Purpose of activity Duration Implementers 1. Improvement of living conditions and temporary settlement 1.1 Construction of new settlements with Improvement of living 2008-2011 State Committee on Refugee and IDP education, health and other necessary standards of 6227 Issues of Azerbaijan Republic, State socio–technical infrastructure, energy, families or 25,550 Committee on State Property Management water supply and multiple storey individuals living in of Azerbaijan Republic, State Committee buildings near the 15 Finnish style dire conditions. on Land and Cartography of Azerbaijan settlementstemporarily inhabited by Republic, State Oil Fund of Azerbaijan 6227 families or 25,550 individuals.1 Republic and relevant city and regional executive authorities 1.2 Establishment of new settlements or Improvement of living 2008-2011 State Committee on Refugee and IDP multiple storey buildings, and new conditions of 2768 Issues of Azerbaijan Republic, State individual houses for 2768 families families or 10,999 Committee on State Property Management consisting of 10,999 individuals IDPs temporarily living of Azerbaijan Republic, State Comitte on temporarily settled in school buildings in the school building Land and Cartography of Azerbaijan of different cities and regions. № 262 and freeing of Republic, State Oil Fund of Azerbaijan 2 the school buildings. Republic and relevant ctiy and region executive authorities 1 Note of UNHCR: Locations will be further defined. -

General Assembly Security Council Seventieth Session Seventy-First Year Agenda Items 35 and 40

United Nations A/70/693–S/2016/62 General Assembly Distr.: General 22 January 2016 Security Council Original: English General Assembly Security Council Seventieth session Seventy-first year Agenda items 35 and 40 Protracted conflicts in the GUAM area and their implications for international peace, security and development The situation in the occupied territories of Azerbaijan Letter dated 21 January 2016 from the Permanent Representative of Azerbaijan to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General Upon instructions from my Government, I have the honour to convey herewith the records of violations of the ceasefire by the Republic of Armenia in November 2015 (see annex). During the reporting period, Armenia violated the ceasefire regime 2,504 times and continued the usage of large-calibre weapons, trench mortars, grenade launchers and other heavy weaponry from its positions in the occupied territories of the Republic of Azerbaijan and from its own territory. As a result, soldier Elshan Ismayilov was killed and soldier Bahruz Nasibov was wounded. Continued occupation of a big portion of the territory of the Republic of Azerbaijan by the armed forces of the Republic of Armenia is the main obstacle to the settlement of the conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan and the only source of the escalation of the situation and the occurrence of hostilities. Azerbaijan will use its legitimate right to take appropriate measures to protect its population and territory from further hostile actions by the Republic of Armenia, the aggressor State, in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations. I should be grateful if you would have the present letter and its annex circulated as a document of the General Assembly, under agenda items 35 and 40, and of the Security Council.