Drawing a Distinction Between Bootleg and Counterfeit Recordings and Implementing a Market Solution Towards Combating Music Piracy in Europe Clifford A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Razorcake Issue #09

PO Box 42129, Los Angeles, CA 90042 www.razorcake.com #9 know I’m supposed to be jaded. I’ve been hanging around girl found out that the show we’d booked in her town was in a punk rock for so long. I’ve seen so many shows. I’ve bar and she and her friends couldn’t get in, she set up a IIwatched so many bands and fads and zines and people second, all-ages show for us in her town. In fact, everywhere come and go. I’m now at that point in my life where a lot of I went, people were taking matters into their own hands. They kids at all-ages shows really are half my age. By all rights, were setting up independent bookstores and info shops and art it’s time for me to start acting like a grumpy old man, declare galleries and zine libraries and makeshift venues. Every town punk rock dead, and start whining about how bands today are I went to inspired me a little more. just second-rate knock-offs of the bands that I grew up loving. hen, I thought about all these books about punk rock Hell, I should be writing stories about “back in the day” for that have been coming out lately, and about all the jaded Spin by now. But, somehow, the requisite feelings of being TTold guys talking about how things were more vital back jaded are eluding me. In fact, I’m downright optimistic. in the day. But I remember a lot of those days and that “How can this be?” you ask. -

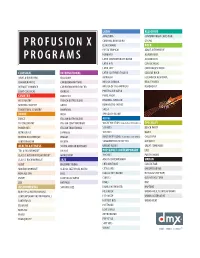

Profusion X Programs

LATIN RELIGIOUS AMAZONIA CONTEMPORARY CHRISTIAN CARNIVAL BRASILEIRO GOSPEL PROFUSION X EL MOCAMBO ROCK FIESTA TROPICAL ADULT ALTERNATIVE HURBANO ALBUM ROCK PROGRAMS LATIN CONTEMPORARY BLEND ALTERNATIVE LATIN HITS CLASSIC ROCK LATIN JAZZ COFFEEHOUSE ROCK CLASSICAL INTERNATIONAL LATIN SOUTHWEST BLEND COLLEGE ROCK ARIAS & OVERTURES BELLISIMA MARIACHI FLASHBACK NEW WAVE CHAMBER MUSIC CARIBBEAN RHYTHMS MÚSICA CUBANA REALITY BITES INTIMATE CHAMBER CARIBBEAN WORLD BLEND MÚSICA DE LAS AMERICAS ROADHOUSE LIGHT CLASSICAL CHINESE PORTUGLISH BLEND COUNTRY EURO HITS PURO AMOR HIT COUNTRY FRENCH BISTRO BLEND REGIONAL MEXICAN MODERN COUNTRY GREEK ROMANCERO LATINO TRADITIONAL COUNTRY HAWAIIAN SALSA DANCE IRISH SPANGLISH BLEND DANCE ITALIAN BISTRO BLEND OLDIES ELECTROSPHERE ITALIAN CONTEMPORARY ‘60S REVOLUTION formerly Rock ‘N’ Roll Oldies) SPECIALTY POWER HITS ITALIAN TRADITIONAL ’70S HITS BEACH PARTY RETRO DISCO JAPANESE ’80S HITS BLUES RIVIERA DISCOTHÈQUE REGGAE MALT SHOP OLDIES formerly Golden Oldies) CHILLTOPIA SUBTERRANEAN RIVIERA SONGWRITERS OF THE ‘70S GOT KIDS? HEALTH & FITNESS SOUTH AFRICAN RHYTHMS UPBEAT OLDIES GREAT STANDARDS ’70S & ’80S WORKOUT UK HITS POP/ADULT CONTEMPORARY LOL! CLASSIC ALTERNATIVE WORKOUT WORLD BEAT ’90S HITS PARTY FAVORS CLASSIC ROCK WORKOUT JAZZ ADULT CONTEMPORARY URBAN GLOW BIG BAND SWING CHÍC BOUTIQUE CLASSIC R&B MODERN WORKOUT CLASSIC JAZZ VOCAL BLEND CITYSCAPES GROOVE LOUNGE NEW AGE SPA JAZZ CLASSIC HITS BLEND HOT JAMZ HIP HOP PUMP! JAZZ VOCAL BLEND CLUB 12 OLD SCHOOL FUNK ZEN RAT PACK DIVAS RAP INSTRUMENTAL SMOOTH -

Mood Music Programs

MOOD MUSIC PROGRAMS MOOD: 2 Pop Adult Contemporary Hot FM ‡ Current Adult Contemporary Hits Hot Adult Contemporary Hits Sample Artists: Andy Grammer, Taylor Swift, Echosmith, Ed Sample Artists: Selena Gomez, Maroon 5, Leona Lewis, Sheeran, Hozier, Colbie Caillat, Sam Hunt, Kelly Clarkson, X George Ezra, Vance Joy, Jason Derulo, Train, Phillip Phillips, Ambassadors, KT Tunstall Daniel Powter, Andrew McMahon in the Wilderness Metro ‡ Be-Tween Chic Metropolitan Blend Kid-friendly, Modern Pop Hits Sample Artists: Roxy Music, Goldfrapp, Charlotte Gainsbourg, Sample Artists: Zendaya, Justin Bieber, Bella Thorne, Cody Hercules & Love Affair, Grace Jones, Carla Bruni, Flight Simpson, Shane Harper, Austin Mahone, One Direction, Facilities, Chromatics, Saint Etienne, Roisin Murphy Bridgit Mendler, Carrie Underwood, China Anne McClain Pop Style Cashmere ‡ Youthful Pop Hits Warm cosmopolitan vocals Sample Artists: Taylor Swift, Justin Bieber, Kelly Clarkson, Sample Artists: The Bird and The Bee, Priscilla Ahn, Jamie Matt Wertz, Katy Perry, Carrie Underwood, Selena Gomez, Woon, Coldplay, Kaskade Phillip Phillips, Andy Grammer, Carly Rae Jepsen Divas Reflections ‡ Dynamic female vocals Mature Pop and classic Jazz vocals Sample Artists: Beyonce, Chaka Khan, Jennifer Hudson, Tina Sample Artists: Ella Fitzgerald, Connie Evingson, Elivs Turner, Paloma Faith, Mary J. Blige, Donna Summer, En Vogue, Costello, Norah Jones, Kurt Elling, Aretha Franklin, Michael Emeli Sande, Etta James, Christina Aguilera Bublé, Mary J. Blige, Sting, Sachal Vasandani FM1 ‡ Shine -

Danger Mouse's Grey Album, Mash-Ups, and the Age of Composition

Danger Mouse's Grey Album, Mash-Ups, and the Age of Composition Philip A. Gunderson © 2004 Post-Modern Culture 15.1 Review of: Danger Mouse (Brian Burton), The Grey Album, Bootleg Recording 1. Depending on one's perspective, Danger Mouse's (Brian Burton's) Grey Album represents a highpoint or a nadir in the state of the recording arts in 2004. From the perspective of music fans and critics, Burton's creation--a daring "mash-up" of Jay-Z's The Black Album and the Beatles' eponymous 1969 work (popularly known as The White Album)--shows that, despite the continued corporatization of music, the DIY ethos of 1970s punk remains alive and well, manifesting in sampling and low-budget, "bedroom studio" production values. From the perspective of the recording industry, Danger Mouse's album represents the illegal plundering of some of the most valuable property in the history of pop music (the Beatles' sound recordings), the sacrilegious re-mixing of said recordings with a capella tracks of an African American rapper, and the electronic distribution of the entire album to hundreds of thousands of listeners who appear vexingly oblivious to current copyright law. That there would be a schism between the interests of consumers and the recording industry is hardly surprising; tension and antagonism characterize virtually all forms of exchange in capitalist economies. What is perhaps of note is that these tensions have escalated to the point of the abandonment of the exchange relationship itself. Music fans, fed up with the high prices (and outright price-fixing) of commercially available music, have opted to share music files via peer-to-peer file sharing networks, and record labels are attempting in response to coerce music fans back into the exchange relationship. -

The Blues Foundation Archives: Immersion and Preservation

The Blues Foundation Archives: Immersion and Preservation Stephanie Swindle Blues music, while still experienced through live performance, should also be documented and preserved in order to honor and promote one of the world's most essential genres of music. The influence of the blues tradition upon rock and roll artists of the nineteen fifties and sixties as well as upon the contemporary R&B and hip-hop musicians is evident in their similar subject matter, rhythmic underpinnings, and featured instrument - the guitar. Therefore, educating the public and providing scholars and fans with the resources to further appreciate and understand the blues is a significant task. The Blues Foundation is a non-profit organization devoted specifically to the preservation perpetuation of the blues. In its possession is twenty-five years worth of archival material that is in desperate need of preservation. The goal for this project is to work in conjunction with the staff and Executive Director of The Blues Foundation in order to write a grant proposal for a National Endowment for the Humanities preservation grant award. Organizing its archives, which is divided into photographs, autographed guitars, audio, video, concert, compact discs and cassettes, and miscellaneous, is the first step in a long process of preservation. In order to organize its media, The Blues Foundation will be served by submitting a grant proposal to the National Endowment for the Humanities to receive funding necessary to undertake such an elaborate project. Due to The Blues Foundation's vast amount of archival wealth, the Foundation and this project, in particular, merit NEH funding consideration. -

2020-2021 Senior Wills

Cypress Ranch HS Choir Senior Wills 2021 Kristen Aviles I don't really know how to start this i feel like i've been writing me senior will since i found out these were a thing but now that i have to ive gone blank. This year has been strange, this isn't the senior year I had built up in my head but there's no way anyone could change our circumstances. We were dealt the cards and now we have to make the best of them. I told myself pretty early that I wouldn't let myself cry over my senior year, that so many people had it worse than me at the moment and the fact that I wouldn't get my last pop show was just a tiny spec of dust compared to what all was happening in the world. At the end of the day though as much as that is true it doesn't make it any less easy. The fact that I didn't get a normal pop show or winter concert, or even a choir olympics. The fact that my senior speech will have to be given on a zoom call, all of that stuff has slowly been chipping away at me this year. The only thing pulling me along is the thought that I traded this for a normal freshman year of college which has been strangely comforting this whole time. So no, this isn't the year i expected or wanted but it's what i got and there is nothing i could do to change that. -

US Copyright Law After GATT

Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review Volume 16 Number 1 Article 1 6-1-1995 U.S. Copyright Law After GATT: Why a New Chapter Eleven Means Bankruptcy fo Bootleggers Jerry D. Brown Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/elr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jerry D. Brown, U.S. Copyright Law After GATT: Why a New Chapter Eleven Means Bankruptcy fo Bootleggers, 16 Loy. L.A. Ent. L. Rev. 1 (1995). Available at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/elr/vol16/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola of Los Angeles Entertainment Law Review by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLES U.S. COPYRIGHT LAW AFTER GATT: WHY A NEW CHAPTER ELEVEN MEANS BANKRUPTCY FOR BOOTLEGGERS Jerry D. Brown* "I am a bootlegger; bootleggin' ain't no good no more." -Blind Teddy Darby' I. INTRODUCTION On December 8, 1994, President Clinton signed into law House Bill 5110, the GATT (General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade) Implementation Act of 1994 . By passing the GATT Implementation Act before the end of 1994, the United States joined 123 countries in forming the World Trade Organization ("WTO"). The WTO is a multilateral trade organization established by GATT 1994, wherein member countries consent to minimum standards of rights, protection and trade regulation. Complying with these standards required the United States to amend existing law in several areas concerning trade and commerce, including areas that regulate intellectual property rights.' * B.A., University of Oklahoma, 1992; J.D., Oklahoma City University School of Law, 1995. -

Locally Owned and Operated

Locally Owned and Operated Vol. 19 - Issue 9 • Sept. 11, 2019 - Oct. 9, 2019 INSIDE: WINERY GUIDE 17th Annual Rib Burn Off 20th – 22nd Ohio Celtic Festival 20th – 22nd 56th Annual Grape Jamboree 28th & 29th Tour - Tribute to Beatles White Album Est. 2000 Movie Reviews FREE! Entertainment, Dining & Leisure Connection Read online at www.northcoastvoice.com North Coast Voice OLD FIREHOUSE 5499 Lake RoadWINERY East • Geneva-on-the Lake, Ohio Restaurant & Tasting Room Open 7 Days Sun. through Thur. Noon - 9 PM Fri. & Sat. Noon to MIDNIGHT Tasting Rooms Entertainment Live Music Weekends! all weekend. (see ad on pg. 7) See inside back cover for listing. FOR ENTERTAINMENT AND Hours: 1-800-Uncork-1 EVENTS, SEE OUR AD ON PG. 7 Monday Closed Hours: Tues thru Thurs noon to 7 pm, Mon. 12-4 • Tues. Closed Fri and Sat noon to 11 pm, Wed. 12-7 • Thurs. 12-8 Sunday noon to 7 pm Fri. 12-9 • Sat. 12-10 • Sun. 12-5 834 South County Line Road 6451 N. RIVER RD., HARPERSIELD, OHIO 4573 Rt. 307 East, Harpersfield, Oh Harpersfield, Ohio 44041 WED. & THURS, 12 - 7, FRI. 12-9 440.415.0661 440.361.3049 SAT. 12- 9, SUN. 12-6 www.laurellovineyards.com www.bennyvinourbanwinery.com WWW.HUNDLEY CELLARS.COM [email protected] [email protected] If you’re in the mood for a palate pleasing wine tasting accompanied by a delectable entree from our restaurant, Ferrante Winery and Ristorante is the place for you! Entertainment every weekend Hours see ad on pg. 6 Stop and try our New Menu! Tasting Room: Mon. -

Safaris to the Heart of All That Jazz

Safaris to the heart of all that jazz.... JoniMitchell.com 2014 Biography Series by Mark Scott, Part 6 of 16 In January of 1974, Joni began an extensive tour of North America with the L.A. Express, wrapping up with three concerts at the New Victoria Theatre in London, England. The final concert at the New Victoria was videotaped and an edited version was broadcast on the BBC television program The Old Grey Whistle Test in November of 1974. Larry Carlton and Joe Sample were playing with The Crusaders at the time and both opted not to go on the road with Joni and the L.A. Express. Guitarist Robben Ford replaced Larry Carlton and Larry Nash filled in for Joe Sample on piano. In a 2011 interview for JoniMitchell.com, Max Bennett said that although the pay was good for this tour, the musicians could have made more money playing gigs in L.A. and doing session work in the recording studios. Max said that the musicians loved the music, however, and that they were treated royally in every way throughout the tour. Excellent food, first class accommodations, limousines, private buses and private planes were all provided for the band’s comfort. Max also made a point of mentioning the quality of the audiences that attended the concerts. Attention was focused on the performances so completely that practically complete silence reigned in the theaters and auditoriums until after the last note of any given song was performed. For Max Bennett, “As far as tours go - I've been on several tours - this was the epitome of any great tour I've ever been on. -

The Live Album Or Many Ways of Representing Performance

Sergio Mazzanti The live album or many ways of representing ... DOI: 10.2298/MUZ1417069M UDK: 78.067.26 The Live Album or Many Ways of Representing Performance Sergio Mazzanti1 University of Macerata (Macerata) Abstract The analysis of live albums can clarify the dialectic between studio recordings and live performances. After discussing key concepts such as authenticity, space, time and place, and documentation, the author gives a preliminary definition of live al- bums, combining available descriptions and comparing them with different typolo- gies and functions of these recordings. The article aims to give a new definition of the concept of live albums, gathering their primary elements: “A live album is an officially released extended recording of popular music representing one or more actually occurred public performances”. Keywords performance, rock music, live album, authenticity Introduction: recording and performance The relationship between recordings and performances is a central concept in performance studies. This topic is particularly meaningful in popular music and even more so in rock music, where the dialectic between studio recordings and live music is crucial for both artists and the audience. The cultural implications of this jux- taposition can be traced through the study of ‘live albums’, both in terms of recordings and the actual live experience. In academic stud- ies there is a large amount of literature on the relationship between recording and performance, but few researchers have paid attention to this particular -

THE GARY MOORE DISCOGRAPHY (The GM Bible)

THE GARY MOORE DISCOGRAPHY (The GM Bible) THE COMPLETE RECORDING SESSIONS 1969 - 1994 Compiled by DDGMS 1995 1 IDEX ABOUT GARY MOORE’s CAREER Page 4 ABOUT THE BOOK Page 8 THE GARY MOORE BAND INDEX Page 10 GARY MOORE IN THE CHARTS Page 20 THE COMPLETE RECORDING SESSIONS - THE BEGINNING Page 23 1969 Page 27 1970 Page 29 1971 Page 33 1973 Page 35 1974 Page 37 1975 Page 41 1976 Page 43 1977 Page 45 1978 Page 49 1979 Page 60 1980 Page 70 1981 Page 74 1982 Page 79 1983 Page 85 1984 Page 97 1985 Page 107 1986 Page 118 1987 Page 125 1988 Page 138 1989 Page 141 1990 Page 152 1991 Page 168 1992 Page 172 1993 Page 182 1994 Page 185 1995 Page 189 THE RECORDS Page 192 1969 Page 193 1970 Page 194 1971 Page 196 1973 Page 197 1974 Page 198 1975 Page 199 1976 Page 200 1977 Page 201 1978 Page 202 1979 Page 205 1980 Page 209 1981 Page 211 1982 Page 214 1983 Page 216 1984 Page 221 1985 Page 226 2 1986 Page 231 1987 Page 234 1988 Page 242 1989 Page 245 1990 Page 250 1991 Page 257 1992 Page 261 1993 Page 272 1994 Page 278 1995 Page 284 INDEX OF SONGS Page 287 INDEX OF TOUR DATES Page 336 INDEX OF MUSICIANS Page 357 INDEX TO DISCOGRAPHY – Record “types” in alfabethically order Page 370 3 ABOUT GARY MOORE’s CAREER Full name: Robert William Gary Moore. Born: April 4, 1952 in Belfast, Northern Ireland and sadly died Feb. -

A Unique One-Off Evening with BUZZCOCKS, the SKIDS & PENETRATION at the Royal Albert Hall

May 28, 2019 01:21 BST A Unique One-Off Evening with BUZZCOCKS, THE SKIDS & PENETRATION at the Royal Albert Hall Buzzcockscan confirm their performance on Friday 21 June 2019 at the Royal Albert Hall. After the tragic death of their frontman and founder member Pete Shelley, the remaining members felt that the evening should become a tribute to Pete and a celebration of his life. They will be performing with some special guest vocalists including Dave Vanian and Captain Sensible (The Damned), Peter Perrett (Only Ones), Thurston Moore (Sonic Youth), Tim Burgess (The Charlatans), Pauline Murray (Penetration), Richard Jobson (The Skids), original Buzzcocks Steve Garvey and John Maher and compere for the evening Paul Morley, with more guests to be announced soon. This will be first time that the Royal Albert Hall have hosted an evening of music featuring a three-band bill of some of the premier artists from the 1970’s punk and new wave scene. Buzzcocks. Formed in Manchester in February 1976 having witnessed the Sex Pistols play, they became the first British punk band to form their own label. They released their debut Spiral Scratch EP on New Hormones later that year. A few months later they signed to United Artists becoming one of the punk and new wave scene’s most enduring and successful bands enjoying consistent chart success with hits such as ‘Ever Fallen In Love (With Someone You Shouldn’t’ve)’, ‘What Do I Get?’ and ‘Promises’. They have toured with Nirvana and Pearl Jam, had a BBC TV show, Never Mind The Buzzcocks named after them.