The Blues Foundation Archives: Immersion and Preservation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Razorcake Issue #09

PO Box 42129, Los Angeles, CA 90042 www.razorcake.com #9 know I’m supposed to be jaded. I’ve been hanging around girl found out that the show we’d booked in her town was in a punk rock for so long. I’ve seen so many shows. I’ve bar and she and her friends couldn’t get in, she set up a IIwatched so many bands and fads and zines and people second, all-ages show for us in her town. In fact, everywhere come and go. I’m now at that point in my life where a lot of I went, people were taking matters into their own hands. They kids at all-ages shows really are half my age. By all rights, were setting up independent bookstores and info shops and art it’s time for me to start acting like a grumpy old man, declare galleries and zine libraries and makeshift venues. Every town punk rock dead, and start whining about how bands today are I went to inspired me a little more. just second-rate knock-offs of the bands that I grew up loving. hen, I thought about all these books about punk rock Hell, I should be writing stories about “back in the day” for that have been coming out lately, and about all the jaded Spin by now. But, somehow, the requisite feelings of being TTold guys talking about how things were more vital back jaded are eluding me. In fact, I’m downright optimistic. in the day. But I remember a lot of those days and that “How can this be?” you ask. -

Queen of the Blues © Photos AP/Wideworld 46 D INAHJ ULY 2001W EASHINGTONNGLISH T EACHING F ORUM 03-0105 ETF 46 56 2/13/03 2:15 PM Page 47

03-0105_ETF_46_56 2/13/03 2:15 PM Page 46 J Queen of the Blues © Photos AP/WideWorld 46 D INAHJ ULY 2001W EASHINGTONNGLISH T EACHING F ORUM 03-0105_ETF_46_56 2/13/03 2:15 PM Page 47 thethe by Kent S. Markle RedRed HotHot BluesBlues AZZ MUSIC HAS OFTEN BEEN CALLED THE ONLY ART FORM J to originate in the United States, yet blues music arose right beside jazz. In fact, the two styles have many parallels. Both were created by African- Americans in the southern United States in the latter part of the 19th century and spread from there in the early decades of the 20th century; both contain the sad sounding “blue note,” which is the bending of a particular note a quar- ter or half tone; and both feature syncopation and improvisation. Blues and jazz have had huge influences on American popular music. In fact, many key elements we hear in pop, soul, rhythm and blues, and rock and roll (opposite) Dinah Washington have their beginnings in blues music. A careful study of the blues can contribute © AP/WideWorld Photos to a greater understanding of these other musical genres. Though never the Born in 1924 as Ruth Lee Jones, she took the stage name Dinah Washington and was later known leader in music sales, blues music has retained a significant presence, not only in as the “Queen of the Blues.” She began with singing gospel music concerts and festivals throughout the United States but also in our daily lives. in Chicago and was later famous for her ability to sing any style Nowadays, we can hear the sound of the blues in unexpected places, from the music with a brilliant sense of tim- ing and drama and perfect enun- warm warble of an amplified harmonica on a television commercial to the sad ciation. -

Memphis Jug Baimi

94, Puller Road, B L U E S Barnet, Herts., EN5 4HD, ~ L I N K U.K. Subscriptions £1.50 for six ( 54 sea mail, 58 air mail). Overseas International Money Orders only please or if by personal cheque please add an extra 50p to cover bank clearance charges. Editorial staff: Mike Black, John Stiff. Frank Sidebottom and Alan Balfour. Issue 2 — October/November 1973. Particular thanks to Valerie Wilmer (photos) and Dave Godby (special artwork). National Giro— 32 733 4002 Cover Photo> Memphis Minnie ( ^ ) Blues-Link 1973 editorial In this short editorial all I have space to mention is that we now have a Giro account and overseas readers may find it easier and cheaper to subscribe this way. Apologies to Kees van Wijngaarden whose name we left off “ The Dutch Blues Scene” in No. 1—red faces all round! Those of you who are still waiting for replies to letters — bear with us as yours truly (Mike) has had a spell in hospital and it’s taking time to get the backlog down. Next issue will be a bumper one for Christmas. CONTENTS PAGE Memphis Shakedown — Chris Smith 4 Leicester Blues Em pire — John Stretton & Bob Fisher 20 Obscure LP’ s— Frank Sidebottom 41 Kokomo Arnold — Leon Terjanian 27 Ragtime In The British Museum — Roger Millington 33 Memphis Minnie Dies in Memphis — Steve LaVere 31 Talkabout — Bob Groom 19 Sidetrackin’ — Frank Sidebottom 26 Book Review 40 Record Reviews 39 Contact Ads 42 £ Memphis Shakedown- The Memphis Jug Band On Record by Chris Smith Much has been written about the members of the Memphis Jug Band, notably by Bengt Olsson in Memphis Blues (Studio Vista 1970); surprisingly little, however has got into print about the music that the band played, beyond general outline. -

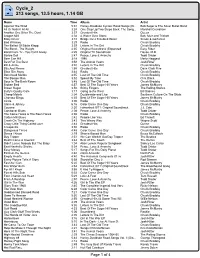

Cycle2 Playlist

Cycle_2 213 songs, 13.5 hours, 1.14 GB Name Time Album Artist Against The Wind 5:31 Harley-Davidson Cycles: Road Songs (Di... Bob Seger & The Silver Bullet Band All Or Nothin' At All 3:24 One Step Up/Two Steps Back: The Song... Marshall Crenshaw Another One Bites The Dust 3:37 Greatest Hits Queen Aragon Mill 4:02 A Water Over Stone Bok, Muir and Trickett Baby Driver 3:18 Bridge Over Troubled Water Simon & Garfunkel Bad Whiskey 3:29 Radio Chuck Brodsky The Ballad Of Eddie Klepp 3:39 Letters In The Dirt Chuck Brodsky The Band - The Weight 4:35 Original Soundtrack (Expanded Easy Rider Band From Tv - You Can't Alway 4:25 Original TV Soundtrack House, M.D. Barbie Doll 2:47 Peace, Love & Anarchy Todd Snider Beer Can Hill 3:18 1996 Merle Haggard Best For The Best 3:58 The Animal Years Josh Ritter Bill & Annie 3:40 Letters In The Dirt Chuck Brodsky Bits And Pieces 1:58 Greatest Hits Dave Clark Five Blow 'Em Away 3:44 Radio Chuck Brodsky Bonehead Merkle 4:35 Last Of The Old Time Chuck Brodsky The Boogie Man 3:52 Spend My Time Clint Black Boys In The Back Room 3:48 Last Of The Old Time Chuck Brodsky Broken Bed 4:57 Best Of The Sugar Hill Years James McMurtry Brown Sugar 3:50 Sticky Fingers The Rolling Stones Buffy's Quality Cafe 3:17 Going to the West Bill Staines Cheap Motels 2:04 Doublewide and Live Southern Culture On The Skids Choctaw Bingo 8:35 Best Of The Sugar Hill Years James McMurtry Circle 3:00 Radio Chuck Brodsky Claire & Johnny 6:16 Color Came One Day Chuck Brodsky Cocaine 2:50 Fahrenheit 9/11: Original Soundtrack J.J. -

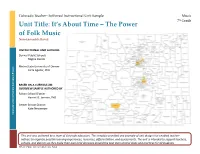

Unit Title: It's About Time – the Power of Folk Music

Colorado Teacher-Authored Instructional Unit Sample Music 7th Grade Unit Title: It’s About Time – The Power of Folk Music Non-Ensemble Based INSTRUCTIONAL UNIT AUTHORS Denver Public Schools Regina Dunda Metro State University of Denver Carla Aguilar, PhD BASED ON A CURRICULUM OVERVIEW SAMPLE AUTHORED BY Falcon School District Harriet G. Jarmon, PhD Center School District Kate Newmeyer Colorado’s District Sample Curriculum Project This unit was authored by a team of Colorado educators. The template provided one example of unit design that enabled teacher- authors to organize possible learning experiences, resources, differentiation, and assessments. The unit is intended to support teachers, schools, and districts as they make their own local decisions around the best instructional plans and practices for all students. DATE POSTED: MARCH 31, 2014 Colorado Teacher-Authored Sample Instructional Unit Content Area Music Grade Level 7th Grade Course Name/Course Code General Music (Non-Ensemble Based) Standard Grade Level Expectations (GLE) GLE Code 1. Expression of Music 1. Perform music in three or more parts accurately and expressively at a minimal level of level 1 to 2 on the MU09-GR.7-S.1-GLE.1 difficulty rating scale 2. Perform music accurately and expressively at the minimal difficulty level of 1 on the difficulty rating scale at MU09-GR.7-S.1-GLE.2 the first reading individually and as an ensemble member 3. Demonstrate understanding of modalities MU09-GR.7-S.1-GLE.3 2. Creation of Music 1. Sequence four to eight measures of music melodically and rhythmically MU09-GR.7-S.2-GLE.1 2. -

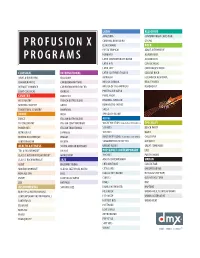

Profusion X Programs

LATIN RELIGIOUS AMAZONIA CONTEMPORARY CHRISTIAN CARNIVAL BRASILEIRO GOSPEL PROFUSION X EL MOCAMBO ROCK FIESTA TROPICAL ADULT ALTERNATIVE HURBANO ALBUM ROCK PROGRAMS LATIN CONTEMPORARY BLEND ALTERNATIVE LATIN HITS CLASSIC ROCK LATIN JAZZ COFFEEHOUSE ROCK CLASSICAL INTERNATIONAL LATIN SOUTHWEST BLEND COLLEGE ROCK ARIAS & OVERTURES BELLISIMA MARIACHI FLASHBACK NEW WAVE CHAMBER MUSIC CARIBBEAN RHYTHMS MÚSICA CUBANA REALITY BITES INTIMATE CHAMBER CARIBBEAN WORLD BLEND MÚSICA DE LAS AMERICAS ROADHOUSE LIGHT CLASSICAL CHINESE PORTUGLISH BLEND COUNTRY EURO HITS PURO AMOR HIT COUNTRY FRENCH BISTRO BLEND REGIONAL MEXICAN MODERN COUNTRY GREEK ROMANCERO LATINO TRADITIONAL COUNTRY HAWAIIAN SALSA DANCE IRISH SPANGLISH BLEND DANCE ITALIAN BISTRO BLEND OLDIES ELECTROSPHERE ITALIAN CONTEMPORARY ‘60S REVOLUTION formerly Rock ‘N’ Roll Oldies) SPECIALTY POWER HITS ITALIAN TRADITIONAL ’70S HITS BEACH PARTY RETRO DISCO JAPANESE ’80S HITS BLUES RIVIERA DISCOTHÈQUE REGGAE MALT SHOP OLDIES formerly Golden Oldies) CHILLTOPIA SUBTERRANEAN RIVIERA SONGWRITERS OF THE ‘70S GOT KIDS? HEALTH & FITNESS SOUTH AFRICAN RHYTHMS UPBEAT OLDIES GREAT STANDARDS ’70S & ’80S WORKOUT UK HITS POP/ADULT CONTEMPORARY LOL! CLASSIC ALTERNATIVE WORKOUT WORLD BEAT ’90S HITS PARTY FAVORS CLASSIC ROCK WORKOUT JAZZ ADULT CONTEMPORARY URBAN GLOW BIG BAND SWING CHÍC BOUTIQUE CLASSIC R&B MODERN WORKOUT CLASSIC JAZZ VOCAL BLEND CITYSCAPES GROOVE LOUNGE NEW AGE SPA JAZZ CLASSIC HITS BLEND HOT JAMZ HIP HOP PUMP! JAZZ VOCAL BLEND CLUB 12 OLD SCHOOL FUNK ZEN RAT PACK DIVAS RAP INSTRUMENTAL SMOOTH -

Lightning in a Bottle

LIGHTNING IN A BOTTLE A Sony Pictures Classics Release 106 minutes EAST COAST: WEST COAST: EXHIBITOR CONTACTS: FALCO INK BLOCK-KORENBROT SONY PICTURES CLASSICS STEVE BEEMAN LEE GINSBERG CARMELO PIRRONE 850 SEVENTH AVENUE, 8271 MELROSE AVENUE, ANGELA GRESHAM SUITE 1005 SUITE 200 550 MADISON AVENUE, NEW YORK, NY 10024 LOS ANGELES, CA 90046 8TH FLOOR PHONE: (212) 445-7100 PHONE: (323) 655-0593 NEW YORK, NY 10022 FAX: (212) 445-0623 FAX: (323) 655-7302 PHONE: (212) 833-8833 FAX: (212) 833-8844 Visit the Sony Pictures Classics Internet site at: http:/www.sonyclassics.com 1 Volkswagen of America presents A Vulcan Production in Association with Cappa Productions & Jigsaw Productions Director of Photography – Lisa Rinzler Edited by – Bob Eisenhardt and Keith Salmon Musical Director – Steve Jordan Co-Producer - Richard Hutton Executive Producer - Martin Scorsese Executive Producers - Paul G. Allen and Jody Patton Producer- Jack Gulick Producer - Margaret Bodde Produced by Alex Gibney Directed by Antoine Fuqua Old or new, mainstream or underground, music is in our veins. Always has been, always will be. Whether it was a VW Bug on its way to Woodstock or a VW Bus road-tripping to one of the very first blues festivals. So here's to that spirit of nostalgia, and the soul of the blues. We're proud to sponsor of LIGHTNING IN A BOTTLE. Stay tuned. Drivers Wanted. A Presentation of Vulcan Productions The Blues Music Foundation Dolby Digital Columbia Records Legacy Recordings Soundtrack album available on Columbia Records/Legacy Recordings/Sony Music Soundtrax Copyright © 2004 Blues Music Foundation, All Rights Reserved. -

Memphis, Tennessee, Is Known As the Home of The

Memphis, Tennessee, is known as the Home of the Blues for a reason: Hundreds of bluesmen honed their craft in the city, playing music in Handy Park and in the alleyways that branch off Beale Street, plying their trade in that street’s raucous nightclubs and in juke joints across the Mississippi River. Mississippians like Ike Turner, B.B. King, and Howlin’ Wolf all passed through the Bluff City, often pausing to cut a record before migrating northward to a better life. Other musicians stayed in Memphis, bristling at the idea of starting over in unfamiliar cities like Chicago, St. Louis, and Los Angeles. Drummer Finas Newborn was one of the latter – as a bandleader and the father of pianist Phineas and guitarist Calvin Newborn, and as the proprietor of his own musical instrument store on Beale Street, he preferred the familiar environs of Memphis. Finas’ sons literally grew up with musical instruments in their hands. While they were still attending elementary school, the two took first prize at the Palace Theater’s “Amateur Night” show, where Calvin brought down the house singing “Your Mama’s On the Bottom, Papa’s On Top, Sister’s In the Kitchen Hollerin’ ‘When They Gon’ Stop.’” Before Calvin followed his brother Phineas to New York to pursue a jazz career, he interacted with all the major players on Memphis’ blues scene. In fact, B.B. King helped Calvin pick out his first guitar. The favor was repaid when the entire Newborn family backed King on his first recording, “Three O’ Clock Blues,” recorded for the Bullet label at Sam Phillips’ Recording Service in downtown Memphis. -

“Salute to the Blues” Takes Center Stage at Radio City Music Hall

Sponsored by Tickets Still Available for the Historic Concert of 2003 “Salute to the Blues” Takes Center Stage at Radio City Music Hall Historic Concert Produced by Martin Scorcese Features Legendary Lineup Including Aerosmith, Gregg Allman, India.Arie, Natalie Cole, Shemekia Copeland, Robert Cray, Chuck D, Macy Gray, Dr. John, B.B. King, The Neville Brothers, Bonnie Raitt, Vernon Reid, Mavis Staples, and more NEW YORK – Feb. 7, 2003 – Renowned artists across multiple music genres and generations will take to the stage at Radio City Music Hall tonight to celebrate their common heritage and passion – the blues. From roots to rock, jazz to rap, musical greats and special surprise guests will join forces for a once-in-a-lifetime “Salute to the Blues” benefit concert – produced by Experience Music Project – honoring the musicians and style that have inspired countless artists around the world. Slated performers include Aerosmith, Gregg Allman, India.Arie, Billy Boy Arnold, Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown, Ruth Brown, Solomon Burke, Natalie Cole, Shemekia Copeland, Robert Cray, Chuck D, Mos Def, Honeyboy Edwards, John Fogerty, Macy Gray, Buddy Guy, Warren Haynes, Levon Helm, David Johansen, Dr. John, Larry Johnson, Angelique Kidjo, B.B. King, Chris Thomas King, Alison Krauss, Lazy Lester, Keb’ Mo’, The Neville Brothers, Odetta, Bonnie Raitt, Vernon Reid, The Jon Spencer Blues Explosion, Mavis Staples, Angie Stone, Hubert Sumlin, James Blood Ulmer, Jimmie Vaughan and Kim Wilson. The concert will also be filmed for theatrical distribution, directed by Antoine Fuqua (“Training Day”) and executive produced by Martin Scorsese. “Salute to the Blues” is exclusively sponsored by Volkswagen and presented by Vulcan Productions with local support provided by W Hotels of New York. -

Mood Music Programs

MOOD MUSIC PROGRAMS MOOD: 2 Pop Adult Contemporary Hot FM ‡ Current Adult Contemporary Hits Hot Adult Contemporary Hits Sample Artists: Andy Grammer, Taylor Swift, Echosmith, Ed Sample Artists: Selena Gomez, Maroon 5, Leona Lewis, Sheeran, Hozier, Colbie Caillat, Sam Hunt, Kelly Clarkson, X George Ezra, Vance Joy, Jason Derulo, Train, Phillip Phillips, Ambassadors, KT Tunstall Daniel Powter, Andrew McMahon in the Wilderness Metro ‡ Be-Tween Chic Metropolitan Blend Kid-friendly, Modern Pop Hits Sample Artists: Roxy Music, Goldfrapp, Charlotte Gainsbourg, Sample Artists: Zendaya, Justin Bieber, Bella Thorne, Cody Hercules & Love Affair, Grace Jones, Carla Bruni, Flight Simpson, Shane Harper, Austin Mahone, One Direction, Facilities, Chromatics, Saint Etienne, Roisin Murphy Bridgit Mendler, Carrie Underwood, China Anne McClain Pop Style Cashmere ‡ Youthful Pop Hits Warm cosmopolitan vocals Sample Artists: Taylor Swift, Justin Bieber, Kelly Clarkson, Sample Artists: The Bird and The Bee, Priscilla Ahn, Jamie Matt Wertz, Katy Perry, Carrie Underwood, Selena Gomez, Woon, Coldplay, Kaskade Phillip Phillips, Andy Grammer, Carly Rae Jepsen Divas Reflections ‡ Dynamic female vocals Mature Pop and classic Jazz vocals Sample Artists: Beyonce, Chaka Khan, Jennifer Hudson, Tina Sample Artists: Ella Fitzgerald, Connie Evingson, Elivs Turner, Paloma Faith, Mary J. Blige, Donna Summer, En Vogue, Costello, Norah Jones, Kurt Elling, Aretha Franklin, Michael Emeli Sande, Etta James, Christina Aguilera Bublé, Mary J. Blige, Sting, Sachal Vasandani FM1 ‡ Shine -

Rhythm Posse Occasionally Worked with Bukka White in Local Juke Facebook.Com/Rhythmposse Joints

father of the Memphis blues guitar style. By the turn of the century, at the age of 12, Stokes worked as a blacksmith, traveling the 25 miles to Memphis on the weekends to sing and play guitar All shows begin at 6:30 In case of inclement weather, Tuesday Night Blues with Don Sane, with whom he developed a long- is held at the House of Rock, 422 Water Street. term musical partnership. Together, they busked on *August 7 will be held at Phoenix Park. the streets and in Church's Park (now W. C. Handy Park) on Memphis' Beale Street. Sane rejoined Stokes May 28 Howard ‘Guitar’ Luedtke & Blue Max for the second day of an August 1928 session for HowardLuedtke.com June 4 Revolver Victor Records, and they produced a two-part RevolverBand.net version of "Tain't Nobody's Business If I Do", a song August 20, 2013 at Owen Park June 11 Bryan Lee well known in later versions by Bessie Smith and BrailleBluesDaddy.com Jimmy Witherspoon, but whose origin lies June 18 Tommy Bentz Band somewhere in the pre-blues era. RhythmRhythm PPosseosse TommyBentz.com In 1929, Stokes and Sane recorded again for June 25 Code Blue with Catya & Sue Catya.net Paramount, resuming their 'Beale Street Sheiks' July 2 Left Wing Bourbon billing for a few cuts. In September, Stokes was back LeftWingBourbon.com on Victor to make what were to be his last July 9 Charlie Parr recordings, this time without Sane, but with Will Batts CharlieParr.com on fiddle. Stokes and Batts were a team as July 16 Deep Water Reunion MySpace.com/DWReunion evidenced by these records, which are both July 23 Steve Meyer with the True Heat Band traditional and wildly original, but their style had (featuring Ben Harder) fallen out of favor with the blues record buying July 30 Ross William Perry public. -

Down on Beale Street

BLUES CITY CULTURAL CENTER Arts for a Better Way of Life Down on Beale Street Some of the most iconic symbols of American music come to life in DOWN ON BEALE STREET, a lively musical depicting notable musicians and the culture that gave birth to the blues. Man, the lead character, guides an aspiring blues singer through the lives of W.C. Handy, Bessie Smith, B.B. King and other legendary artists who left their historic footprints on Beale Street. Written by Levi Frazier Jr in 1972, DOWN ON BEALE STREET has been presented on numerous stages in Memphis and at the Richard Allen Culture Center in New York. It was first performed in 1973 at LeMoyne-Owen College during the W.C. Handy Festival. In 2016, it was performed at Minglewood Hall for over 2,000 students. Over the years, it has been viewed by over 100,000 people through live performances or public broadcasting. In African-American Theatre: An Historical & Critical Analysis, theatre historian and critic Samuel Hay described DOWN ON BEALE STREET as a musical revue that “highlights the denizens and the good times of such Beale Street spots as the Palace Theatre in Memphis. The significance of all of these musicals-with-messages is that they finally achieve what Dubois was seeking when he asked Cole in 1909 to write protest musical comedies for Broadway.” 1 Lesson Overview and Background Information As a music genre, the blues was originated by African Americans in the Deep South. Rooted in African rhythms, spirituals and field songs, it reflected the hard lives and misery experienced by blacks living in a segregated and disenfranchised society.