David Hoare Consulting Cc Postnet Suite No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Driftsands Nature Reserve Complex PAMP

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Driftsands Nature Reserve is situated on the Cape Flats, approximately 25 km east of Cape Town on the National Route 2, in the Western Cape Province. The reserve is situated adjacent to the Medical Research Centre in Delft and is bounded by highways and human settlement on all sides. Driftsands is bound in the northwest by the R300 and the National Route 2 and Old Faure road in the south. The northern boundary is bordered by private landowners, while the eastern boundary is formed by Mfuleni Township. The Nature Reserve falls within the City of Cape Town Metropolitan Municipality. The reserve experiences a Mediterranean-type climate with warm dry summers, and cool wet winter seasons. Gale force winds from the south east prevail during the summer months, while during the winter months, north westerly winds bring rain. Driftsands Nature Reserve represents of one of the largest remaining remnants of intact Cape Flats Dune Strandveld which is classified as Endangered, and harbours at least two Endangered Cape Flats endemics, Muraltia mitior and Passerina paludosa. The Kuils River with associated floodplain wetlands, dune strandveld depressions and seeps are representative of a wetland type that has been subjected to high cumulative loss, and provides regulatory ecosystem services such as flood attenuation, ground water recharge/discharge and water quality improvement. The site provides access for cultural and/or religious practices and provides opportunities for quality curriculum based environmental education. Driftsands Nature Reserve is given the highest priority rating within the Biodiversity Network (BioNet), the fine scale conservation plan for the City of Cape Town. -

Sand Mine Near Robertson, Western Cape Province

SAND MINE NEAR ROBERTSON, WESTERN CAPE PROVINCE BOTANICAL STUDY AND ASSESSMENT Version: 1.0 Date: 06 April 2020 Authors: Gerhard Botha & Dr. Jan -Hendrik Keet PROPOSED EXPANSION OF THE SAND MINE AREA ON PORTION4 OF THE FARM ZANDBERG FONTEIN 97, SOUTH OF ROBERTSON, WESTERN CAPE PROVINCE Report Title: Botanical Study and Assessment Authors: Mr. Gerhard Botha and Dr. Jan-Hendrik Keet Project Name: Proposed expansion of the sand mine area on Portion 4 of the far Zandberg Fontein 97 south of Robertson, Western Cape Province Status of report: Version 1.0 Date: 6th April 2020 Prepared for: Greenmined Environmental Postnet Suite 62, Private Bag X15 Somerset West 7129 Cell: 082 734 5113 Email: [email protected] Prepared by Nkurenkuru Ecology and Biodiversity 3 Jock Meiring Street Park West Bloemfontein 9301 Cell: 083 412 1705 Email: gabotha11@gmail com Suggested report citation Nkurenkuru Ecology and Biodiversity, 2020. Section 102 Application (Expansion of mining footprint) and Final Basic Assessment & Environmental Management Plan for the proposed expansion of the sand mine on Portion 4 of the Farm Zandberg Fontein 97, Western Cape Province. Botanical Study and Assessment Report. Unpublished report prepared by Nkurenkuru Ecology and Biodiversity for GreenMined Environmental. Version 1.0, 6 April 2020. Proposed expansion of the zandberg sand mine April 2020 botanical STUDY AND ASSESSMENT I. DECLARATION OF CONSULTANTS INDEPENDENCE » act/ed as the independent specialist in this application; » regard the information contained in this -

Towards Ecological Restoration Strategies for Penisula Shale

Towards ecological restoration strategies for Peninsula Shale Renosterveld: testing the effects of disturbance-intervention treatments on seed germination on Devil’s Peak, Cape Town by Penelope Anne Waller Dissertation presented in fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Science at the University of Cape Town, Department of Environmental and Geographical Sciences Private Bag X3, Rondebosch 7701, Cape Town University of Cape Town Supervisor: Dr Pippin Anderson Co-supervisor: Dr Pat Holmes September 2013 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town D eclarationeclarationeclaration I, the undersigned, know the meaning of plagiarism and declare that all of the work in the document, save for that which is properly acknowledged, is my own. University of Cape Town Signature: _____________________________ Date: ____________________________ i AAbstractbstractAbstract The ecological restoration of Peninsula Shale Renosterveld is essential to redress its conservation- target shortfall. The ecosystem is Critically Endangered and, along with all other renosterveld types in the Cape lowlands, declared ‘totally irreplaceable’. Further to conserving all extant remnants, ecological restoration is required to play a critical part in securing biodiversity and to meeting conservation targets. Remnants of Peninsula Shale Renosterveld are situated either side of the Cape Town city bowl and, despite formal protection, areas of the ecosystem are degraded and require restoration intervention. -

Rdna) Organisation

OPEN Heredity (2013) 111, 23–33 & 2013 Macmillan Publishers Limited All rights reserved 0018-067X/13 www.nature.com/hdy ORIGINAL ARTICLE Dancing together and separate again: gymnosperms exhibit frequent changes of fundamental 5S and 35S rRNA gene (rDNA) organisation S Garcia1 and A Kovarˇı´k2 In higher eukaryotes, the 5S rRNA genes occur in tandem units and are arranged either separately (S-type arrangement) or linked to other repeated genes, in most cases to rDNA locus encoding 18S–5.8S–26S genes (L-type arrangement). Here we used Southern blot hybridisation, PCR and sequencing approaches to analyse genomic organisation of rRNA genes in all large gymnosperm groups, including Coniferales, Ginkgoales, Gnetales and Cycadales. The data are provided for 27 species (21 genera). The 5S units linked to the 35S rDNA units occur in some but not all Gnetales, Coniferales and in Ginkgo (B30% of the species analysed), while the remaining exhibit separate organisation. The linked 5S rRNA genes may occur as single-copy insertions or as short tandems embedded in the 26S–18S rDNA intergenic spacer (IGS). The 5S transcript may be encoded by the same (Ginkgo, Ephedra) or opposite (Podocarpus) DNA strand as the 18S–5.8S–26S genes. In addition, pseudogenised 5S copies were also found in some IGS types. Both L- and S-type units have been largely homogenised across the genomes. Phylogenetic relationships based on the comparison of 5S coding sequences suggest that the 5S genes independently inserted IGS at least three times in the course of gymnosperm evolution. Frequent transpositions and rearrangements of basic units indicate relatively relaxed selection pressures imposed on genomic organisation of 5S genes in plants. -

Biodiversity Survey: Vacant Site in Sedgefield

BIODIVERSITY SURVEY: VACANT SITE IN SEDGEFIELD January 2020 Mark Berry Environmental Consultants Pr Sci Nat (reg. no. 400073/98) PhD in Botany Tel: 083 286-9470, Fax: 086 759-1908, E-mail: [email protected] 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................... 2 2 PROPOSED LAND USE ................................................................................................................... 2 3 TERMS OF REFERENCE ................................................................................................................. 2 4 METHODOLOGY .............................................................................................................................. 3 5 LIMITATIONS TO THE STUDY ........................................................................................................ 3 6 LOCALITY & SITE DESCRIPTION ................................................................................................... 4 7 BIOGEOGRAPHICAL CONTEXT ..................................................................................................... 6 8 VEGETATION & FLORA .................................................................................................................. 7 9 CONSERVATION STATUS & BIODIVERSITY NETWORK........................................................... 10 10 CONCLUSION & RECOMMENDATIONS ...................................................................................... 11 -

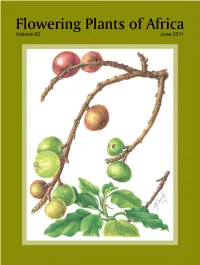

Albuca Spiralis

Flowering Plants of Africa A magazine containing colour plates with descriptions of flowering plants of Africa and neighbouring islands Edited by G. Germishuizen with assistance of E. du Plessis and G.S. Condy Volume 62 Pretoria 2011 Editorial Board A. Nicholas University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, RSA D.A. Snijman South African National Biodiversity Institute, Cape Town, RSA Referees and other co-workers on this volume H.J. Beentje, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, UK D. Bridson, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, UK P. Burgoyne, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, RSA J.E. Burrows, Buffelskloof Nature Reserve & Herbarium, Lydenburg, RSA C.L. Craib, Bryanston, RSA G.D. Duncan, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Cape Town, RSA E. Figueiredo, Department of Plant Science, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, RSA H.F. Glen, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Durban, RSA P. Goldblatt, Missouri Botanical Garden, St Louis, Missouri, USA G. Goodman-Cron, School of Animal, Plant and Environmental Sciences, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, RSA D.J. Goyder, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, UK A. Grobler, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, RSA R.R. Klopper, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, RSA J. Lavranos, Loulé, Portugal S. Liede-Schumann, Department of Plant Systematics, University of Bayreuth, Bayreuth, Germany J.C. Manning, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Cape Town, RSA A. Nicholas, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Durban, RSA R.B. Nordenstam, Swedish Museum of Natural History, Stockholm, Sweden B.D. Schrire, Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, UK P. Silveira, University of Aveiro, Aveiro, Portugal H. Steyn, South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria, RSA P. Tilney, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, RSA E.J. -

South Africa

ran Forestry Department Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations GLOBAL FOREST RESOURCES ASSESSMENT COUNTRY REPORTS OUTH FRICA S A FRA2005/004 Rome, 2005 FRA 2005 – Country Report 004 SOUTH AFRICA The Forest Resources Assessment Programme Sustainably managed forests have multiple environmental and socio-economic functions important at the global, national and local scales, and play a vital part in sustainable development. Reliable and up- to-date information on the state of forest resources - not only on area and area change, but also on such variables as growing stock, wood and non-wood products, carbon, protected areas, use of forests for recreation and other services, biological diversity and forests’ contribution to national economies - is crucial to support decision-making for policies and programmes in forestry and sustainable development at all levels. FAO, at the request of its member countries, regularly monitors the world’s forests and their management and uses through the Forest Resources Assessment Programme. This country report forms part of the Global Forest Resources Assessment 2005 (FRA 2005), which is the most comprehensive assessment to date. More than 800 people have been involved, including 172 national correspondents and their colleagues, an Advisory Group, international experts, FAO staff, consultants and volunteers. Information has been collated from 229 countries and territories for three points in time: 1990, 2000 and 2005. The reporting framework for FRA 2005 is based on the thematic elements of sustainable forest management acknowledged in intergovernmental forest-related fora and includes more than 40 variables related to the extent, condition, uses and values of forest resources. -

Isolation and Characterization of Natural Products from Selected Rhus Species

ISOLATION AND CHARACTERIZATION OF NATURAL PRODUCTS FROM SELECTED RHUS SPECIES MKHUSELI KOKI MTECH CHEMISTRY, CAPE PENINSULA UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy JUNE 2020 Department of Chemistry Faculty of Natural Sciences University of the Western Cape Supervisor: Prof. T.W Mabusela http://etd.uwc.ac.za/ ABSTRACT Searsia is the more recent name for the genus (Rhus) that contains over 250 individual species of flowering plants in the family Anacardiaceae. Research conducted on Searsia extracts to date indicates a promising potential for this plant group to provide renewable bioproducts with the following reported desirable bioactivities; antimicrobial, antifungal, antiviral, antimalarial, antioxidant, antifibrogenic, anti-inflammatory, antimutagenic, antithrombin, antitumorigenic, cytotoxic, hypoglycaemic, and leukopenic (Rayne and Mazza, 2007, Salimi et al., 2015). Searsia glauca, Searsia lucida and Searsia laevigata were selected for this study. The aim of this study was to isolate, elucidate and evaluate the biological activity of natural products occurring in the plants selected. From the three Searsia species seven known terpenes were isolated and characterized using chromatographic techniques and spectroscopic techniques: Moronic acid (C1 & C5), 21β- hydroxylolean-12-en-3-one (C2), Lupeol (C11a), β-Amyrin (C11b & C10), α-amyrin (C11c) and a mixture β-Amyrin (C12a) and α-amyrin (C12b) of fatty acid ester. Six known flavonoids were isolated myricetin-3-O-β-galactopyranoside (C3), Rutin (C4), quercetin (C6), Apigenin (C7), Amentoflavone (C8), quercetin-3-O-β-glucoside (C9). The in vitro anti-diabetic activity of the extracts was investigated on selected carbohydrate digestive enzymes. The enzyme inhibition effect was conducted at 2.0 mg/ml for both carbohydrate digestive enzymes. -

Bmm Whs Nomination Dossier Appendix H: Biodiversity Inventory

Biodiversity Inventory - Appendix H BMM WHS NOMINATION DOSSIER APPENDIX H: BIODIVERSITY INVENTORY 1 BARBERTON – MAKHONJWA MOUNTAIN LANDS WORLD HERITAGE SITE PROJECT Biodiversity Resource Inventory by Anthony Emery, Marc Stalmans and Tony Ferrar July 2016 Version 1.1 Biodiversity Resource Inventory 2 Biodiversity Resource Inventory: Executive Summary The Biodiversity Resource Inventory forms one of the base documents for the development of the Barberton Makhonjwa Mountains (BMM) World Heritage Site (WHS) nomination dossier to UNESCO. The aim of the document is to summarise and assess the biodiversity found within the BMM WHS. To achieve this currently known biodiversity data has been collated, summarised and mapped, special emphasis has been placed on the features of the local Centre of Plant Endemism and the functioning of ecosystems. These biodiversity data have been assessed according to their conservation status and main ecological threats and trends. These resources will form the bases of providing the main biodiversity attraction for visitors. The BMM WHS is located in the mountainous areas surrounding Barberton through to Badplaas. The Core Area of the BMM WHS is made up of four nature reserves located in an arc from Badplaas through the Nkomazi Wilderness, down the Komati River Valley and into the mountains of the Songimvelo Nature Reserve and the Mountainlands Nature Reserve. This area forms an important conservation corridor between the Kruger National Park and the Highveld and conservation areas within Swaziland. The importance of this area has been highlighted in numerous previous conservation and tourism development initiatives such as the Biodiversity Tourism Corridor and the Songimvelo-Malolotja Transfrontier Conservation Area. -

NUMBERED TREE SPECIES LIST in SOUTH AFRICA CYATHEACEAE 1 Cyathea Dregei 2 Cyathea Capensis Var. Capensis ZAMIACEAE 3 Encephalart

NUMBERED TREE SPECIES LIST IN SOUTH AFRICA 23 Hyphaene coriacea CYATHEACEAE 24 Hyphaene petersiana 1 Cyathea dregei 25 Borassus aethiopum 2 Cyathea capensis var. capensis 26 Raphia australis 27 Jubaeopsis caffra ZAMIACEAE 3 Encephalartos altensteinii ASPHODELACEAE 3.1 Encephalartos eugene-maraisii 28 Aloe barberae 3.2 Encephalartos arenarius 28.1 Aloe arborescens 3.3 Encephalartos brevifoliolatus 28.2 Aloe africana 3.4 Encephalartos ferox 28.3 Aloe alooides 4 Encephalartos friderici-guilielmi 28.4 Aloe angelica 5 Encephalartos ghellinckii 28.5 Aloe candelabrum 5.1 Encephalartos inopinus 28.6 Aloe castanea 5.2 Encephalartos lanatus 28.7 Aloe comosa 6 Encephalartos laevifolius 28.8 Aloe excelsa var. excelsa 7 Encephalartos latifrons 29 Aloe dichotoma 8 Encephalartos senticosus 29.1 Aloe dolomitica 8.1 Encephalartos lehmannii 29.2 Aloe ferox 9 Encephalartos longifolius 29.3 Aloe khamiesensis 10 Encephalartos natalensis 29.4 Aloe littoralis 11 Encephalartos paucidentatus 29.5 Aloe marlothii subsp. marlothii 12 Encephalartos princeps 29.6 Aloe plicatilis 12.5 Encephalartos relictus 29.7 Aloe marlothii subsp. orientalis 13 Encephalartos transvenosus 30 Aloe pillansii 14 Encephalartos woodii 30.1 Aloe pluridens 14.1 Encephalartos heenanii 30.2 Aloe ramosissima 14.2 Encephalartos dyerianus 30.3 Aloe rupestris 14.3 Encephalartos middelburgensis 30.4 Aloe spicata 14.4 Encephalartos dolomiticus 30.5 Aloe speciosa 14.5 Encephalartos aemulans 30.6 Aloe spectabilis 14.6 Encephalartos hirsutus 30.7 Aloe thraskii 14.7 Encephalartos msinganus 14.8 Encephalartos -

Ecological Impact Assessment Proposed Saldanha Bay Network Strengthening Project, Saldanha Bay Local Municipality, Western Cape Province

ECOLOGICAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT PROPOSED SALDANHA BAY NETWORK STRENGTHENING PROJECT, SALDANHA BAY LOCAL MUNICIPALITY, WESTERN CAPE PROVINCE JANUARY 2017 Prepared by: Prepared for: Afzelia Environmental Consultants Savannah Environmental P.O. Box 37069, Tel: 011 656 3237 Overport, 4067 Fax: 086 684 0547 Tel: 031 303 2835 Fax: 086 692 2547 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Declaration I, Leigh-Ann de Wet, declare that - • I act as an independent specialist in this application; • I do not have and will not have any vested interest (either business, financial, personal or other) in the undertaking of the proposed activity, other than remuneration for work performed in terms of the Environmental Impact Assessment Regulations, 2010 and 2014; • I will perform the work relating to the application in an objective manner, even if this results in views and findings that are not favourable to the applicant; • I declare that there are no circumstances that may compromise my objectivity in performing such work; • I have expertise in conducting the specialist report relevant to this application, including knowledge of the Act, regulations and any guidelines that have relevance to the proposed activity; • I will comply with the Act, regulations and all other applicable legislation; • I have not and will not engage in, conflicting interests in the undertaking of the activity; • I undertake to disclose to the applicant and the competent authority all material information in my possession that reasonably has or may have the potential of influencing any decision to be taken with respect to the application by the competent authority; and the objectivity of any report, plan or document to be prepared by myself for submission to the competent authority; • All the particulars furnished by me in this form are true and correct. -

Technical Report for the Mpumalanga Biodiversity Sector Plan – MBSP 2015

Technical Report for the Mpumalanga Biodiversity Sector Plan – MBSP 2015 June 2015 Authored by: Mervyn C. Lötter Mpumalanga Tourism &Parks Agency Private bag X1088 Lydenburg, 1120 1 Citation: This document should be cited as: Lötter, M.C. 2015. Technical Report for the Mpumalanga Biodiversity Sector Plan – MBSP. Mpumalanga Tourism & Parks Agency, Mbombela (Nelspruit). ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There are many individuals and organisations that contributed towards the success of the MBSP. In particular we gratefully acknowledge the ArcGIS software grant from the ESRI Conservation Program. In addition the WWF-SA and SANBIs Grasslands Programme played an important role in supporting the development and financing parts of the MBSP. The development of the MBSP spatial priorities took a few years to complete with inputs from many different people and organisations. Some of these include: MTPA scientists, Amanda Driver, Byron Grant, Jeff Manuel, Mathieu Rouget, Jeanne Nel, Stephen Holness, Phil Desmet, Boyd Escott, Charles Hopkins, Tony de Castro, Domitilla Raimondo, Lize Von Staden, Warren McCleland, Duncan McKenzie, Natural Scientific Services (NSS), South African National Biodiversity Institute (SANBI), Strategic Environmental Focus (SESFA),Birdlife SA, Endangered Wildlife Trust, Graham Henning, Michael Samways, John Simaika, Gerhard Diedericks, Warwick Tarboton, Jeremy Dobson, Ian Engelbrecht, Geoff Lockwood, John Burrows, Barbara Turpin, Sharron Berruti, Craig Whittington-Jones, Willem Froneman, Peta Hardy, Ursula Franke, Louise Fourie, Avian Demography